Mr. Arkadin

Mr. Arkadin (first released in Spain, 1955), known in Britain as Confidential Report, is a French-Spanish-Swiss coproduction film, written and directed by Orson Welles and shot in several Spanish locations, including Costa Brava, Segovia, Valladolid, and Madrid. Filming took place throughout Europe in 1954, and scenes shot outside Spain include locations in London, Munich, Paris, the French Riviera, and the Château de Chillon in Switzerland.

| Mr. Arkadin AKA Confidential Report | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Orson Welles |

| Produced by | Louis Dolivet Orson Welles |

| Screenplay by | Orson Welles |

| Based on | original radio scripts by Ernest Bornemann and Orson Welles from The Lives of Harry Lime originally produced by Harry Alan Towers (uncredited) |

| Starring | Orson Welles Robert Arden Paola Mori Akim Tamiroff Michael Redgrave |

| Music by | Paul Misraki |

| Edited by | Renzo Lucidi |

| Distributed by | Filmorsa/Cervantes Films/Sevilla (Spain), Warner Bros. (USA) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 99 minutes ("Corinth" version) 93 minutes (Spanish version) 95 minutes (public domain version) 98 minutes (Confidential Report) 106 minutes (2006 edit) |

| Country | France Spain Switzerland |

| Language | English Spanish |

| Box office | 517,788 admissions (France)[1] |

Plot

Guy Van Stratten (Robert Arden), a small-time American smuggler working in Europe, is found desperately trying to get a man called Jakob Zouk (Akim Tamiroff) to leave his bare, ruinous room in Munich and come with him to safety. When Zouk alleges that he's dying and doesn't want to be disturbed, Stratten desperately tells him why he has to come. We see the story in flashback as he narrates it to Zouk.

In the flashback, Stratten is with his girlfriend and accomplice Mily (Patricia Medina) in Naples when a man named Bracco is knifed in the street. Bracco does not want his last moments to be taken up with doctors and police, and he rewards the couple for not calling them with two names that he says will be profitable to them: he names Gregory Arkadin to Stratten, and one "Sophie" to Mily. They get away as Bracco dies, and approach Arkadin, a famous and super-wealthy businessman (Orson Welles), to see if the murder and vague references to his "secret" can be used to blackmail him. Arkadin's only human tie in a life of power and pleasure is his daughter Raina (Paola Mori), and Stratten manages to strike up an acquaintance with her and thus get into Arkadin's castle in Spain. He and Raina also develop feelings for each other, though they cover them up with cool sophistication.

To Stratten's surprise and Raina's displeasure, Arkadin shows them a dossier he has had compiled about Stratten and Mily's criminal career. He then hires Stratten to find out the truth about his own past; he says he woke up in a square in Switzerland in a new suit with a large sum of money in his pocket, and no memory of who he was or what he had done before that day in 1927. He wants Stratten to tell him.

Stratten goes all over the world, picking up clues, while Mily cruises with Arkadin on his yacht and tries to get clues from his own lips. From such people as the proprietor of a flea circus, a junk-shop owner, an impoverished noblewoman in Paris, and a heroin addict he tortures with withdrawal, Stratten learns that the pre-1927 Arkadin was involved in a sex trafficking ring in Warsaw that trapped girls who thought they were joining a dance school, and sent them to be prostitutes in South America. "Sophie" turns out to be the former leader of the ring and Arkadin's old girlfriend, from whom he stole the money that was in his pocket in the square. She is now married to a Mexican general, and is a relaxed, tolerant woman who remembers Arkadin with affection and has no intention of publicizing his past.

However, while learning all this, Stratten notices that Arkadin is following him and re-interviewing the people he has found. He is puzzled by this, and more puzzled when Raina tells him her father does not have amnesia and thus the story he told of why he hired him was false. Meanwhile, Arkadin learns to his chagrin that Raina actually cares for Stratten and that Stratten wants to marry her.

At Arkadin's Christmas Eve party in Munich, just before he goes to Zouk's room and tells him all this, Stratten learns to his horror that everybody he tracked down and talked to about Arkadin's past is now dead. Mily has also been found dead, and the clues have been arranged to point to him as the murderer; the police are looking for him. He realizes that Arkadin's real motive for hiring him was to uncover whatever evidence of Arkadin's sordid past so that Arkadin can eliminate said evidence. Arkadin especially does not want his beloved daughter to learn of his past. Zouk is the last surviving member of the sex trafficking ring, and once Zouk is dead, Arkadin will murder Stratten to complete the cover-up.

Even after hearing this, Zouk doesn't care whether he dies of cancer or murder, but Stratten manages to get him to his own hotel room and goes out to get him the special meal he requests. Arkadin intercepts him and mockingly helps him get the meal, but when he takes it to his room, Zouk has been stabbed to death.

Stratten realizes that his only hope of survival now is to get to Raina in Spain and tell her her father's secret; he manages to get the very last seat on the crowded Christmas Eve plane to Barcelona. Arkadin fails to persuade the airline to throw Stratten off and give him the seat, and when he pleads with the other passengers for a seat at a tremendous price, Stratten makes them think he is a drunk impostor. Stratten reaches the Barcelona airport just ahead of the one-man private plane Arkadin then hires; Raina meets him, but is almost immediately summoned to the control tower to talk to her father on the radio. With no time to tell her everything, Stratten coaxes her to say over the radio "he told me everything". When Arkadin hears the lie, the radio link goes silent, and Arkadin commits suicide by falling out of his rolling plane, which later crashes.

Raina understands why Stratten did this to her father, but is unhappy, and Stratten is unhappy that she is now tremendously rich and thus beyond him. He stays at the airport, and she drives away with a previous boyfriend from England.

Cast

- Orson Welles as Gregory Arkadin

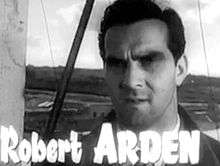

- Robert Arden as Guy Van Stratten

- Patricia Medina as Mily

- Paola Mori as Raina Arkadin

- Akim Tamiroff as Jakob Zouk

- Grégoire Aslan as Bracco

- Jack Watling as Bob, the Marquess of Rutleigh

- Mischa Auer as the Professor

- Peter van Eyck as Thaddeus

- Michael Redgrave as Burgomil Trebitsch

- Suzanne Flon as Baroness Nagel

- Frederick O'Brady as Oskar

- Katina Paxinou as Sophie Radzweickz Martinez

- Manuel Requena as Jesus Martinez

- Tamara Shayne as the woman who hides Zouk

- Terence Langdon as Mr. Arkadin's Secretary

- Gert Fröbe as a Munich Detective

- Eduard Linker as a Munich Policeman

- Gordon Heath as the pianist in the Cannes bar

- Annabel as the woman with a baguette in Paris

- Irene López Heredia as Sofía (only in Spanish version)

- Amparo Rivelles as Baroness Nagel (only in Spanish version)

Production

The story was based on several episodes of the radio series The Lives of Harry Lime, which in turn was based on the character Welles portrayed in The Third Man.[2] The main inspiration for the plot was the episode entitled Man of Mystery though some elements may have been lifted from an episode of the radio show Ellery Queen, entitled "The Case of the Number Thirty-One," chiefly the similar-sounding name "George Arkaris," the mysterious birthplace, the French Riviera property and the Spanish castle for example. Most of the other key elements for Arkadin's character come from a real-life arms dealer, Basil Zaharoff.

In addition, several different versions of the film were released. In his 1991 essay, "The Seven Arkadins", film historian Jonathan Rosenbaum identified seven different versions of the story, and since its initial publication, a further two versions have emerged including a novel and a stage play. When Welles missed an editing deadline, Producer Louis Dolivet took the film out of his hands and released several edits of the film, none of which were approved by Welles. Adding to the confusion is a novel of the same title that was credited to Welles, though Welles claimed that he was unaware of the book's existence until he saw a copy in a bookshop.

In his interview for the BBC's Arena series first shown in 1982, Welles described Mr. Arkadin as the "biggest disaster" of his life, due to his loss of creative control.[3] The film was not released in the United States until 1962.[4] Some consolation for Welles came in the form of Paola Mori who played the role of Arkadin's daughter. Mori was the stage name for the Countess Paola Di Girfalco, who would become Welles’ third wife.[5] In addition, the film started Welles's longtime relationship with Spain, where he lived for several periods in his life.

Released in some parts of Europe as Confidential Report, this film shares themes and stylistic devices with The Third Man (1949). The Criterion Collection has produced a three-DVD box set that includes three separate versions of Mr. Arkadin including a comprehensive re-edit that combines material taken from all the known versions of the film. Though the creators of this "restored" version express their doubts as to the "correctness" of altering another artist's work, this new cut is far and away the most comprehensible and easy to follow of any of the known versions. Also included are three of the Harry Lime radio plays reported to have been written by Welles and upon which he certainly based Arkadin. A copy of the Arkadin novelization — which may or may not have been adapted by Welles — is also included in the Criterion Collection as are commentary tracks from Welles' film scholars Jonathan Rosenbaum and James Naremore.

Multiple versions of Mr. Arkadin

In his 1991 essay, "The Seven Arkadins", film historian Jonathan Rosenbaum identified seven different versions of the story, and since its initial publication, a further two versions have emerged.[6]

Pre-film versions

1. Three episodes of the radio series The Lives of Harry Lime, written, directed by and starring Welles. The basic plot of a wealthy Mr. Arkadian (spelt with three As in this version) commissioning a confidential report on his former life can be found in the episode "Man of Mystery" (first broadcast 11 April 1952), while the episode "Murder on the Riviera" (first broadcast 23 May 1952) and the final episode "Greek Meets Greek" (first broadcast 25 July 1952) both contain plot elements repeated in the film. Note that in the film, the popular Harry Lime character from The Third Man is replaced by the less sympathetic Guy Van Stratten, since Welles did not own the copyright to the Lime character as character rights had been bought by Harry Alan Towers for the Lives of Harry Lime radio series.[7]

2. Masquerade, an early version of the screenplay of what would eventually become Mr. Arkadin, has substantial differences from the film versions. The screenplay follows a strictly chronological structure rather than the back-and-forth structure of the film. Many of the scenes in the film are set in different countries, and a lengthy sequence in Mexico is entirely missing from the final film.

Different edits of the film released in Welles's lifetime

Crucially, none of the versions available before 2006 contained all the footage found in the others; each had some elements missing from other versions, and each has substantial editing differences from the others.

3. The main Spanish-language version of Mr. Arkadin. (93 mins) This was filmed back-to-back with the English-language version and was the first to be released, premiering in Madrid in March 1955. Although the cast and crew were largely the same, two characters were played by Spanish actors - Amparo Rivelles plays Baroness Nagel, and Irene Lopez Heredia plays Sophie Radzweickz Martinez. The two scenes with the actresses were reshot in Spanish, but all others had Spanish dubbing over English dialogue. This one credits Robert Arden as "Bob Harden".

4. There is a second, longer Spanish-language cut of Mr. Arkadin, which was unknown to Rosenbaum at the time he wrote The Seven Arkadins. (He confessed in the essay to having seen only brief clips of one version.) This one credits Robert Arden as "Mark Sharpe".[8]

5. "Confidential Report" (98 mins) - the most common European release print of Mr. Arkadin, which premiered in London in August 1955. Differences to this version include the presence of off-screen narration from Van Stratten. Rosenbaum speculates that the editing of this version was based on an early draft of Welles' screenplay, since its exposition is far simpler than the "Corinth" version's.

6. The "Corinth" version of Mr. Arkadin. (99 mins) - named after Corinth Films, the initial US distributor of the film.[9] Until the 2006 re-edit, it was believed to be the closest version to Welles' conception. Peter Bogdanovich discovered its existence in 1961, and secured its first US release in 1962, seven years after alternative versions of the film came out in Europe.

7. The most widely seen version of Mr. Arkadin, which was made for television/ home video release and is now in the public domain. (95 mins) It entirely removes the film's flashback structure and presents a simpler, linear narrative. Rosenbaum describes it as "the least satisfactory version", which is a "clumsily truncated" edit of the "Corinth" version, often editing out half-sentences, making some dialogue incomprehensible.[10] As this version is in the public domain, the vast majority of DVD releases are of this version, often in poor-quality transfers.

Novelization

8. The novel Mr. Arkadin was first published in French, in Paris in 1955; and then in English in 1956, both in London and New York. Welles was credited as author, and the book's dustjacket boasted "It is perhaps surprising that Orson Welles … has not written a novel before."

"I didn't write one word of that novel. Nor have I ever read it," Welles told Peter Bogdanovich. "Somebody wrote it in French to be published in serial form in the newspapers. You know — to promote the picture. I don't know how it got under hardcovers, or who got paid for that."[11]

Welles always denied authorship of the book, and French actor-writer Maurice Bessy, who is credited as translating it into French, was long rumoured to be the real author. Rosenbaum suggested that the book was written in French and then translated into English, since lines from the script were approximations that seemed to have been translated from English to French to English again. Research by film scholar François Thomas in the papers of Louis Dolivet has uncovered documentary proof that Bessy was indeed the author.[12]

Criterion edit (2006)

9. Whilst no version of the film can claim to be definitive as Welles never finished editing the film, this version is likely the closest to Welles' original vision.[13] It was compiled in 2006 by Stefan Drössler of the Munich Film Museum and Claude Bertemes of the Cinémathèque municipale de Luxembourg, with both Peter Bogdanovich and Jonathan Rosenbaum giving technical assistance. It uses all available English-language footage, and attempts to follow Welles' structure and editing style as closely as possible and also incorporating his comments over the years on where the other editions of the film went wrong. However, it still only remains an approximation - for instance, Welles remarked that his version of the film began with a woman's body (Mily) on a beach, including a close-up which makes her identity apparent to the audience. Whilst the Criterion edit restores the film opening on a woman's body on the beach, only a long shot exists (taken from the Corinth version) in which it is unclear whose body it is; and so no close-up of Mily could be used as the footage no longer exists.

" The Criterion edit" (106 mins) was released in a 3-disc DVD set which included:

- the "Corinth" version of the film

- the "Confidential Report" version of the film

- a copy of the novel

- clips from one of the Spanish-language versions

- the three Harry Lime radio episodes on which the film was based

Reception

Japanese film director Shinji Aoyama listed Confidential Report as one of the Greatest Films of All Time in 2012. He said, "No other movie is destructive as Confidential Report, which gives me different emotions every time I see it. Achieving this kind of indetermination in a film is the highest goal that I always hope for, but can never achieve."[14]

References

- Orson Welles box office information in France at Box Office Story

- DVD Pick: Mr. Arkadin (Criterion Collection)

- Interview with Orson Welles, 1982, Arena, BBC Television

- "The Bootleg files : Mr. Arkadin", filmthreat.com

- Welles over Europe, BBC 4, with Simon Callow

- Jonathan Rosenbaum, "The Seven Arkadins", Jonathan Rosenbaum (ed.), Discovering Orson Welles, (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 2007) pp.146-62

- Torsten Dewi (22 May 2012), Harry Alan Towers - More Bang for the Buck!, retrieved 4 September 2018

- The existence of a second Spanish-language cut is mentioned in Joseph McBride, Whatever Happened to Orson Welles? A portrait of an independent career (UNiversity of Kentucky Press, Lexington, Kentucky, 2006) p.117

- Clinton Heylin (1 June 2006). Despite the System: Orson Welles Versus the Hollywood Studios. Chicago Review Press, Incorporated. pp. 275–. ISBN 978-1-56976-422-0.

- Jonathan Rosenbaum, "The Seven Arkadins", Jonathan Rosenbaum (ed.), Discovering Orson Welles, (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 2007) pp.147, 159. Note that in the original article, Rosenbaum erroneously believed this version to be an edit of "Confidential Report" rather than the "Corinth" version. The updated introduction to the 2007 reprint of the article corrects this mistake.

- Welles, Orson, and Peter Bogdanovich, edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum, This is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers 1992 ISBN 0-06-016616-9 hardcover, page 239

- New introduction, Jonathan Rosenbaum, "The Seven Arkadins", Jonathan Rosenbaum (ed.), Discovering Orson Welles, (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 2007) p.147

- "THE ESSENTIAL ORSON WELLES - MR. ARKADIN". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 2015.

[...] the most comprehensive version in existence, reedited by the Filmmuseum München after Welles’s passing to restore the film closer to his intended vision.

- Aoyama, Shinji (2012). "The Greatest Films Poll". Sight & Sound. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mr. Arkadin. |

- Mr. Arkadin on IMDb

- Mr. Arkadin at AllMovie

- Mr. Arkadin at the TCM Movie Database

- Welles Amazed: The Lives of Mr. Arkadin an essay by J. Hoberman at the Criterion Collection