Morenada

The Morenada is a highland folk dance whose origin is in debate. This dance is practiced mainly in Bolivia[1] as well as in Peru[2][3][4] and in recent years with Bolivian or Peruvian immigration in Chile, Argentina and other countries.

| Morenada | |

|---|---|

| Cultural origins | African and Native American communities in Bolivia and Peru |

| Typical instruments | Matraca, cymbal, bass drum, trumpet, tuba. |

| Other topics | |

| Music of Bolivia Music of Peru | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bolivia |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

|

|

Festivals |

|

Literature

|

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media

|

|

Sport |

|

Monuments

|

|

Symbols |

|

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of Peru |

|---|

_alternative_version.svg.png) |

|

History

RecentPresidency of Martín Vizcarra (2018-current) |

|

Arts and literature

|

|

Entertainment

|

|

|

|

Peoples |

|

Peru portal |

Morenada is one of the most representative dances of Bolivian culture. This importance stands out for the dissemination of dance and music in the patron and civic festivals in different regions of the country. The morenada was declared Cultural Heritage of Bolivia in 2011, through Law No. 135, for its recognized importance at national and national level international.[5] In turn, this dance is performed during the Carnaval de Oruro, in honor of the Virgen del Socavón, declared a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. It can also be performed appreciate mainly in the Fiesta del Gran Poder of the city of La Paz, and in all the folkloric entrances that are held in most of the towns, localities, and in many of the neighborhoods of each of the cities of Bolivia ( in the city of La Paz there are at least 246 annual folkloric entries, in each of which the morenada is danced) .

In Peru, la morenada is a typical dance in the Peruvian highlands, in the Puno region, and is part of the Feast of the Virgin of La Candelaria, Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[6][7]

[8] It is also practiced and disseminated in the departments of Tacna and Moquegua due to the presence of Aymara population.[9]

Origins

Dance whose origin dates back to the colonial era and is inspired by the slave trade, from the transfer of blacks brought by the Spanish conquerors to work as workers in the silver mines in the Viceroyalty of Peru, recently initiated by the Aymara dressed up as blacks and representing characters like the caporal and the black troop. The brunette dance evokes the days of the colony. He was born precisely in the brotherhoods of slaves from Africa who mocked the dances of the white lords.

Then, the dance of the "brunettes", changes its name in a historical process of acceptance of it, towards all social classes in Oruro, Bolivia. Such is the case of the "Comparsa de Morenos de los Veleros" born in 1913 and "Comparsa de los Morenos" of 1924 founded by Aymara migrant families and that come from the ancient dancers of the "moraine comparsas" of the mid-century XIX, finally adopts the name of Morenada in 1950 and 1954, respectively.

African slavery in Potosí theory

The most commonly shared theory says that the dance was inspired by the sufferings of the African slaves brought to Bolivia in order to work in the Silver Mines of Potosí. The enormous tongue of the dark masks is meant to represent the physical state of these mines workers and the rattling of the Matracas are frequently associated with the rattling of the slaves' chains. However, there is no evidence that these African slaves actually worked in the mines, although there is much evidence that they worked in the Casa de la Moneda (mint) in the production of coins and in domestic service.

African population of the Puno highlands

In the colonial era of the Viceroyalty of Peru, there is already a black population register in the Puno highlands, as documented in 1602 Ludovico Bertonio, an Italian Jesuit based in Juli, Puno. "To these blacks, the Andean population called them: Ch'ara or yanaruna.58 And to the pronounced geta they had, they said: Lakha llint'a. At the beginning of the 17th century, according to Gonzales Holguín and Bertonio, the Africans were I alluded to them interchangeably as blacks or brunettes.[10]

Another hypothesis comes from the Department of Puno in Peru, on the shores of Lake Titicaca (Puno). At the beginning of the 20th century, the presence of brunettes in devotion to the Virgen de la Candelaria is described in newspapers of the time:

- "Yesterday ... Three games of brunettes and numerous indigenous, have traveled the streets of the town" (El Eco de Puno, 1912)

- "From this morning they continue to travel the streets, the moorings, doing the usual home visits" (El Eco de Puno, 1916)

- “The most sumptuous presentation of brunettes is due in the calendar to the first days of February. It is an indigenous offering to the Virgin of the Candelaria, patron of Puno ”(El Pueblo, 1923)

- “The attendance of numerous“ morenos ”troupes gave the festival a tone of deep joy” (El Eco de Puno, 1932)

Afro-Bolivian community in Yungas theory

A second theory relates the Morenada to the Afro Bolivians living in the Yungas region and the stamping of grapes for wine production. According to this, the barrel-like Moreno-costumes would represent the barrel containing the wine. However, in the Yungas region there has never been any wine cultivation. At first sight this makes the theory seem extremely unprovable, but the texts sung in the Morenada contain hints as to wine cultivation for a long time. In addition, if one goes far enough back in history, one can discover that there were Afro-Bolivians working in vineyards - in other regions, such as Chuquisaca. Nowadays there might not be any Afro-Bolivians left where there are wineyards, but when the dance was created, there might have been.

Cave paintings in the Lake Titicaca theory

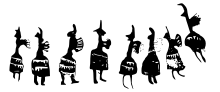

The third theory relates the Morenada to the Aymara Culture of the Lake Titicaca. Places such as Achacachi claim to be the place of origin of the "Fish Dance", as the Morenada in this region also is called. Some murals about 200–300 years old were found in the region, showing Morenada dancers and there still is a strong tradition of making elaborately embroidered Morenada costumes. The multicolored costumes of the Morenada are somewhat similar to the ones of Tinku dancers.

Gallery

Morenada mask showing exaggerated features to represent the physical state.

Morenada mask showing exaggerated features to represent the physical state.- Morenada parade at the Oruro Carnival, 2012

Morenada Bellavista parade at the Puno Candelaria, 2013

Morenada Bellavista parade at the Puno Candelaria, 2013 Morenada Laykakota parade at the Puno Candelaria, 2011

Morenada Laykakota parade at the Puno Candelaria, 2011

References

- Ministerio de Culturas y Turismo (29 August 2018). "La Morenada Patrimonio Cultural de Bolivia". Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "Danzas folclóricas se lucen por primera vez en el desfile de Fiestas Patrias del Perú". Ministerio de Cultura (in Spanish). 29 July 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Salinas, Eduardo, Robles, Joel (30 July 2018). "Danzas, música y gallardía en un desfile con sabor a Perú". La República (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "Las danzas típicas conquistaron al público en la Gran Parada y Desfile Cívico Militar". RPP (in Spanish). 30 July 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-09-02. Retrieved 2019-12-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://larepublica.pe/archivo/685728-escenificando-el-origen-de-la-morenada-presentaran-fiesta-de-la-candelaria

- https://elcomercio.pe/peru/puno/puno-vivio-fiesta-danzas-honor-virgen-candelaria-noticia-496485

- Fernández, Carlos (11 February 2018). "Puno vivió fiesta de danzas en honor a la Virgen de la Candelaria". El Comercio (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- http://www.diariosinfronteras.pe/2018/07/30/fiesta-de-virgen-de-copacabana-tendra-23-bloques-de-morenadas/

- http://www.losandes.com.pe/Sociedad/20110206/46094.html