Moray eel

Moray eels, or Muraenidae (/ˈmɒreɪ, məˈreɪ/), are a family of eels whose members are found worldwide. There are approximately 200 species in 15 genera which are almost exclusively marine, but several species are regularly seen in brackish water, and a few are found in fresh water.[2]

| Moray eel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Moray eel in the Maldives | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Anguilliformes |

| Suborder: | Muraenoidei |

| Family: | Muraenidae Rafinesque, 1810 |

| Genera | |

|

See text. | |

The English name, from the early 17th century, derives from the Portuguese moréia, which itself derives from the Latin mūrēna, in turn from the Greek muraina, a kind of eel.[3][4]

Anatomy

The dorsal fin extends from just behind the head along the back and joins seamlessly with the caudal and anal fins. Most species lack pectoral and pelvic fins, adding to their serpentine appearance. Their eyes are rather small; morays rely mostly on their highly developed sense of smell, lying in wait to ambush prey.

The body is generally patterned. In some species, the inside of the mouth is also patterned. Their jaws are wide, framing a protruding snout. Most possess large teeth used to tear flesh or grasp slippery prey items. A relatively small number of species, for example the snowflake moray (Echidna nebulosa) and zebra moray (Gymnomuraena zebra), primarily feed on crustaceans and other hard-shelled animals, and they have blunt, molar-like teeth suitable for crushing.[5]

Morays secrete a protective mucus over their smooth, scaleless skin, which in some species contains a toxin. They have much thicker skin and high densities of goblet cells in the epidermis that allows mucus to be produced at a higher rate than in other eel species. This allows sand granules to adhere to the sides of their burrows in sand-dwelling morays,[6] thus making the walls of the burrow more permanent due to the glycosylation of mucins in mucus. Their small, circular gills, located on the flanks far posterior to the mouth, require the moray to maintain a gap to facilitate respiration.

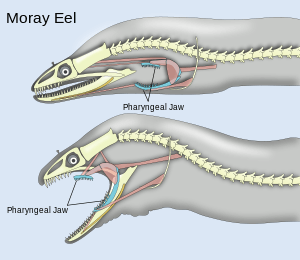

Jaw

The pharyngeal jaws of morays are located farther back in the head and closely resemble the oral jaws (complete with tiny "teeth"). When feeding, morays launch these jaws into the mouth cavity, where they grasp prey and transport it into the throat. Moray eels are the only known animals that use pharyngeal jaws to actively capture and restrain prey in this way.[7][8][9]

In addition to the presence of pharyngeal jaws, morays' mouth openings extend far back into the head, compared to fishes which feed using suction. In the action of lunging at prey and biting down, water flows out the posterior side of the mouth opening, reducing waves in front of the eel which would otherwise displace prey. Thus, aggressive predation is still possible even with reduced bite times.[10] In at least one species, the California moray (Gymnothorax mordax), teeth in the roof of the mouth are able to fold down as prey slides backwards, thus preventing the teeth from breaking and maintaining a hold on prey as it is transported to the throat.

Differing shapes of the jaw and teeth reflect the respective diets of different species of moray eel. Evolving separately multiple times across the Muraenidae, short, rounded jaws and molar-like teeth allow durophagous eels (e.g. Gymnomuraena zebra and genus Echidna) to consume crustaceans, while other piscivorous genera of Muraenidae have pointed jaws and longer teeth.[11][12][13] These morphological patterns carry over to teeth positioned on the pharyngeal jaw.[14][15]

Feeding behavior

Morays are opportunistic, carnivorous predators and feed primarily on smaller fish, octopuses, squid, cuttlefish and crustaceans. Groupers, barracudas and sea snakes are among their few known predators, making many morays (especially the larger species) apex predators in their ecosystems.

Cooperative hunting

Reef-associated roving coral groupers (Plectropomus pessuliferus) have been observed to recruit giant morays to help them hunt. The invitation to hunt is initiated by head-shaking. This style of hunting may allow morays to flush prey from niches not accessible to groupers.[16][17][18]

Habitat

The moray eel can be found in both freshwater habitats and saltwater habitats. The vast majority of species are strictly marine, never entering freshwater. Of the few species known to live in freshwater, the most well-known is Gymnothorax polyuranodon.[19][20]

Within the marine realm, morays are found in shallow water nearshore areas, continental slopes, continental shelves, deep benthic habitats, and mesopelagic zones of the ocean, and in both tropical and temperate environments.[20] Tropical oceans are typically located near the equator, whereas temperate oceans are typically located away from the equator. Most species are found in tropical or subtropical environments, with only a few species (e.g., Gymnothorax mordax and Gymnothorax prasinus) are found in subtropical ocean environments.

Although the moray eel can occupy both tropical oceans and temperate oceans, as well as both freshwater and saltwater, the majority of moray eels occupy warm saltwater environments, which contain reefs.[21] Within the tropical oceans and temperate oceans, the moray eel occupies shelters, such as dead patch reefs and coral rubble rocks, and less frequently occupies live coral reefs.[21]

Taxonomy

Classifications

Class: Actinopterygii[22]

Order: Anguilliformes[22]

Family: Muraenidae[22]

_Family_Muraenidae_Puerto_Rico.jpeg)

Genera

There are currently around 202 known species of moray eels, divided among 16 genera. These genera fall into the two sub-families of Muraeninae and Uropterygiinae, which can be distinguished by the location of their fins.[23] In Muraeninae the dorsal fin is found near the gill slits and runs down the back of the eel, while the anal fin is behind the anus.[23] The Uropterygiinnae, on the other hand, are defined by both their dorsal and anal fin being located at the end of their tails.[23] Though this distinction can be seen between the two sub-families, there are still many varieties of genera within Muraeninae and Uropterygiinae. Of these, the genus Gymnothorax is by far the broadest, including more than half of the total number of species.

List of genera according to the World Register of Marine Species :

- sub-family Muraeninae Rafinesque, 1815

- genus Diaphenchelys McCosker & Randall, 2007 -- 1 species

- genus Echidna Forster, 1788 -- 11 species

- genus Enchelycore Kaup, 1856 -- 13 species

- genus Enchelynassa Kaup, 1855 -- 1 species

- genus Gymnomuraena Lacepède, 1803 -- 1 species

- genus Gymnothorax Bloch, 1795 -- 125 species

- genus Monopenchelys Böhlke & McCosker, 1982 -- 1 species

- genus Muraena Linnaeus, 1758 -- 10 species

- genus Pseudechidna Bleeker, 1863 -- 1 species

- genus Rhinomuraena Garman, 1888 -- 1 species (ribbon moray eel)

- genus Strophidon McClelland, 1844 -- 1 species (long-tailed moray eel)

- sub-family Uropterygiinae Fowler, 1925

- genus Anarchias Jordan & Starks, 1906 -- 11 species

- genus Channomuraena Richardson, 1848 -- 2 species

- genus Cirrimaxilla Chen & Shao, 1995 -- 1 species

- genus Scuticaria Jordan & Snyder, 1901 -- 2 species

- genus Uropterygius Rüppell, 1838 -- 20 species

Echidna nebulosa

Echidna nebulosa.jpeg) Enchelynassa vinolentus

Enchelynassa vinolentus Gymnomuraena zebra

Gymnomuraena zebra Gymnothorax favagineus

Gymnothorax favagineus Monopenchelys acuta

Monopenchelys acuta Muraena helena

Muraena helena- Pseudechidna brummeri

_(6052858389).jpg) Rhinomuraena quaesita

Rhinomuraena quaesita

Strophidon sathete

Strophidon sathete

Evolution

Elongation

The moray eel's elongation is due to an increase in the number of vertebrae, rather than a lengthening of each individual vertebra or a substantial decrease in body depth.[24] Interestingly, vertebrae have been added asynchronously between the pre-tail ("precaudal") and tail ("caudal") regions, unlike other groups of eels such as Ophicthids and Congrids.[25]

Relationship with humans

Aquarium trade

Several moray species are popular among aquarium hobbyists for their hardiness, flexible diets, and disease resistance. The most commonly traded species are the snowflake moray (Echidna nebulosa), the zebra moray (Gymnomuraena zebra), and the golden-tailed moray (Gymnothorax miliaris). Several other species are occasionally seen, more are difficult to obtain and can command a steep price on the market.[26]

Ciguatera poisoning

Moray eels, particularly the giant moray (Gymnothorax javanicus) and yellow-edged moray (G. flavimarginatus), are known to accumulate high levels of ciguatoxins, unlike other reef fish.[27][28] Ciguatera poisoning is characterised by neurological, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular problems. In morays, the toxins are most concentrated in the liver.[28] In an especially remarkable instance, 57 people in the Northern Mariana Islands were poisoned after eating just the head and half of a cooked G. flavimarginatus.[29] Thus, morays are not recommended for human consumption.

References

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2009). "Muraenidae" in FishBase. January 2009 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2010). "Gymnothorax polyuranodon" in FishBase. January 2010 version.

- "Moray - Definition of moray in English - Oxford Dictionaries". oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- "moray". thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Randall, J. E. (2005). Reef and Shore Fishes of the South Pacific. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2698-1

- Fishelson L (September 1996). "Skin morphology and cytology in marine eels adapted to different lifestyles". The Anatomical Record. 246 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199609)246:1<15::AID-AR3>3.0.CO;2-E. PMID 8876820.

- Mehta RS, Wainwright PC (September 2007). "Raptorial jaws in the throat help moray eels swallow large prey". Nature. 449 (7158): 79–82. Bibcode:2007Natur.449...79M. doi:10.1038/nature06062. PMID 17805293.

- Hopkin, Michael (2007-09-05). "Eels imitate alien: Fearsome fish have protruding jaws in their throats to grab prey". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news070903-11. Retrieved 2007-09-06.

- "Moray Eels Are Uniquely Equipped to Pack Big Prey Into Their Narrow Bodies - NSF - National Science Foundation". Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Mehta RS, Wainwright PC (February 2007). "Biting releases constraints on moray eel feeding kinematics". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (Pt 3): 495–504. doi:10.1242/jeb.02663. PMID 17234619.

- Reece JS, Bowen BW, Smith DG, Larson A (November 2010). "Molecular phylogenetics of moray eels (Muraenidae) demonstrates multiple origins of a shell-crushing jaw (Gymnomuraena, Echidna) and multiple colonizations of the Atlantic Ocean". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 57 (2): 829–35. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.07.013. PMID 20674752.

- Mehta RS (January 2009). "Ecomorphology of the moray bite: relationship between dietary extremes and morphological diversity". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 82 (1): 90–103. doi:10.1086/594381. PMID 19053846.

- Collar DC, Reece JS, Alfaro ME, Wainwright PC, Mehta RS (June 2014). "Imperfect morphological convergence: variable changes in cranial structures underlie transitions to durophagy in moray eels". The American Naturalist. 183 (6): E168–84. doi:10.1086/675810. PMID 24823828.

- Böhlke, ed. Eugenia B. (1989). Fishes of the Western North Atlantic, part 9 : Orders Anguilliformes and Saccopharyngiformes. New Haven: Sears Foundation for marine research, Yale University. ISBN 978-0935868456. OCLC 30092375.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- 1876-1970., Gregory, William K. (William King) (2002). Fish skulls : a study of the evolution of natural mechanisms. Malabar, Fla.: Krieger Pub. ISBN 978-1575242149. OCLC 48892721.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- In the December 2006 issue of the journal Public Library of Science Biology, a team of biologists announced the discovery of interspecies cooperative hunting involving morays. The biologists, who were engaged in a study of Red Sea cleaner fish (fish that enter the mouths of other fish to rid them of parasites), made the discovery.An Amazing First: Two Species Cooperate to Hunt | LiveScience

- Bshary R, Hohner A, Ait-el-Djoudi K, Fricke H (December 2006). "Interspecific communicative and coordinated hunting between groupers and giant moray eels in the Red Sea". PLOS Biology. 4 (12): e431. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040431. PMC 1750927. PMID 17147471.

- Vail A.L., Manica A., Bshary R., Referential gestures in fish collaborative hunting, in Nature Communications, vol. 4, 2013.

- Ebner, Brendan C.; Fulton, Christopher J.; Donaldson, James A.; Schaffer, Jason (2015). "Distinct habitat selection by freshwater morays in tropical rainforest streams". Ecology of Freshwater Fish. 25 (2): 329–335. doi:10.1111/eff.12213. ISSN 0906-6691.

- Tsukamoto, Katsumi; Watanabe, Shun; Kuroki, Mari; Aoyama, Jun; Miller, Michael J. (2014). "Freshwater habitat use by a moray eel species, Gymnothorax polyuranodon, in Fiji shown by otolith microchemistry". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 97 (12): 1377–1385. doi:10.1007/s10641-014-0228-9. ISSN 0378-1909.

- Young, Robert F.; Winn, Howard E.; Montgomery, W. L. (2003). "Activity Patterns, Diet, and Shelter Site Use for Two Species of Moray Eels, Gymnothorax moringa and Gymnothorax vicinus, in Belize". Copeia. 2003 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2003)003[0044:APDASS]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0045-8511.

- Cope, E. D. (1889). "Synopsis of the Families of Vertebrata". The American Naturalist. 23 (274): 849–877. doi:10.1086/275018.

- Reece, Joshua (January 2010). "Phylogenetics and Phylogeography of Moray Eels (Muraenidae)". Washington University Open Scholarship.

- Mehta, Rita S.; Reece, Joshua S. (July 2013). "Evolutionary history of elongation and maximum body length in moray eels (Anguilliformes: Muraenidae)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 109 (4): 861–875. doi:10.1111/bij.12098.

- Mehta RS, Ward AB, Alfaro ME, Wainwright PC (December 2010). "Elongation of the body in eels". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 50 (6): 1091–105. doi:10.1093/icb/icq075. PMID 21558261.

- ], PINT [ www.pint.com. "Morays! | Saltwater & Reef | Feature Articles | TFH Magazine®". www.tfhmagazine.com. Retrieved 2018-08-29.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Chan TY (April 2016). "Characteristic Features and Contributory Factors in Fatal Ciguatera Fish Poisoning--Implications for Prevention and Public Education". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 94 (4): 704–9. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0686. PMC 4824207. PMID 26787145.

- Chan TY (June 2017). "Regional Variations in the Risk and Severity of Ciguatera Caused by Eating Moray Eels". Toxins. 9 (7): 201. doi:10.3390/toxins9070201. PMC 5535148. PMID 28672845.

- Khlentzos, Constantine T. (1950-09-01). "Seventeen Cases of Poisoning Due to Ingestion of an Eel, Gymnothorax Flavimarginatus 1". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. s1-30 (5): 785–793. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1950.s1-30.785. ISSN 0002-9637. PMID 14771403.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muraenidae. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Moray. |

- Moray Eels Grab Prey With Alien Jaws

- Smith, J.L.B. 1962. The moray eels of the Western Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Ichthyological Bulletin; No. 23. Department of Ichthyology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa.