Moral emotions

Moral emotions are a variety of social emotion that are involved in forming and communicating moral judgments and decisions, and in motivating behavioral responses to one's own and others' moral behavior.[1][2][3]

Background

Moral reasoning has been the focus of most study of morality dating all the way back to Plato and Aristotle. The emotive side of morality has been looked upon with disdain, as subservient to the higher, rational, moral reasoning, with scholars like Piaget and Kohlberg touting moral reasoning as the key forefront of morality.[4] However, in the last 30–40 years, there has been a rise in a new front of research: moral emotions as the basis for moral behavior. This development began with a focus on empathy and guilt, but has since moved on to encompass new emotional scholarship on emotions such as anger, shame, disgust, awe, and elevation. With the new research, theorists have begun to question whether moral emotions might hold a larger in determining morality, one that might even surpass that of moral reasoning.[2]

Definitions

There have generally been two approaches taken by philosophers to define moral emotion. The first "is to specify the formal conditions that make a moral statement (e.g., that is prescriptive, that it is universal, such as expedience)".[5] This first approach is more tied to language and the definitions we give to a moral emotions. The second approach "is to specify the material conditions of a moral issue, for example, that moral rules and judgments 'must bear on the interest or welfare either of society as a whole or at least of persons other than the judge or agent'".[6] This definition seems to be more action based. It focuses on the outcome of a moral emotion. The second definition is more preferred because it is not tied to language and therefore can be applied to prelinguistic children and animals. Moral emotions are "emotions that are linked to the interests or welfare either of society as a whole or at least of persons other than the judge or agent."[2](pp853)

Types of moral emotion

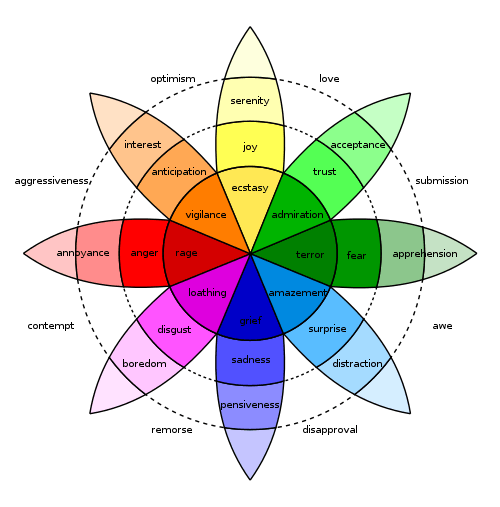

There is a debate whether there is a set of basic emotions or if there are "scripts or set of components that can be mixed and matched, allowing for a very large number of possible emotions".[2] Even those arguing for a basic set acknowledge that there are variants of each emotion (psychologist Paul Ekman calls these variants "families"[7]). According to Jonathan Haidt:

The principal moral emotions can be divided into two large and two small joint families. The large families are the "other-condemning" family, in which the three brothers are contempt, anger, and disgust (and their many children, such as indignation and loathing), and the "self-conscious" family (shame, embarrassment, and guilt)…[T]he two smaller families the "other-suffering" family (compassion) and the "other-praising" family (gratitude and elevation).[2]

Haidt would suggest that the higher the emotionality of a moral agent, the more likely the agent is to act morally. He uses the term "disinterested elicitor" to describe an event or situation that provokes emotions in us even when these emotions do not have anything to do with our own personal welfare. It is these elicitors that cause people to participate in what he calls "prosocial action tendencies" (actions that benefit society). Haidt explains moral emotions as "emotion families", in which each family contains emotions that may be similar although not exactly the same. These moral emotions are provoked by eliciting events that often lead to prosocial action tendencies. Each person's likelihood of prosocial action is determined by his or her degree of emotionality.

According to Haidt, there are four different moral emotion families: the "other-condemning emotions" (contempt, anger, disgust), the "self-conscience emotions" (shame, embarrassment, and guilt), the "other suffering emotions" (compassion and sympathy), and the "other-praising family" (gratitude, awe, and elevation). These emotions are moral emotions based on grounds that they can all lead to prosocial action tendencies.[2]

Moral emotions and behavior

Empathy also plays a large role in altruism. The empathy-altruism hypothesis states that feelings of empathy for another leads to an altruistic motivation to help that person.[8] In contrast, there may also be an egoistic motivation to help someone in need. This is the Hullian tension-reduction model in which personal distress caused by another in need leads the person to help in order to alleviate their own discomfort.[9]

Batson, Klein, Highberger, and Shaw conducted experiments where they manipulated people through the use of empathy-induced altruism to make decisions that required them to show partiality to one individual over another. The first experiment involved a participant from each group to choose someone to experience a positive or negative task. These groups included a non-communication, communication/low-empathy, and communication/high-empathy. They were asked to make their decisions based on these standards resulting in the communication/high-empathy group showing more partiality in the experiment than the other groups due to being successfully manipulated emotionally. Those individuals who they successfully manipulated reported that despite feeling compelled in the moment to show partiality, they still felt they had made the more "immoral" decision since they followed an empathy-based emotion rather than adhering to a justice perspective of morality.[8]

Batson, Klein, Highberger, & Shaw conducted two experiments on empathy-induced altruism, proposing that this can lead to actions that violate the justice principle. The second experiment operated similarly to the first using low-empathy and high-empathy groups. Participants were faced with the decision to move an ostensibly ill child to an "immediate help" group versus leaving her on a waiting list after listening to her emotionally-driven interview describing her condition and the life it has left her to lead. Those who were in the high-empathy group were more likely than those in the low-empathy group to move the child higher up the list to receive treatment earlier. When these participants were asked what the more moral choice was, they agreed that the more moral choice would have been to not move this child ahead of the list at the expense of the other children. In this case, it is evident that when empathy induced altruism is at odds with what is seen as moral, oftentimes empathy induced altruism has the ability to win out over morality.[8]

Recently neuroscientist Jean Decety, drawing on empirical research in evolutionary theory, developmental psychology, social neuroscience, and psychopathy, argued that empathy and morality are neither systematically opposed to one another, nor inevitably complementary.[10][11]

Emmons (2009) defines gratitude as a natural emotional reaction and a universal tendency to respond positively to another's benevolence. Gratitude is motivating and leads to what Emmons' describes as "upstream reciprocity". This is the passing on of benefits to third parties instead of returning benefits to one's benefactors (Emmons, 2009).

In the context of social networking behavior, research from Brady, Wills, Jost, Tucker, and Van Bavel (2017) shows that the expression of moral emotion amplifies the extent to which moral and political ideals are disseminated in social media platforms. Analyzing a large sample of Twitter communications on polarizing issues, such as gun control, same-sex marriage, and climate change, results indicated that the presence of moral-emotional language in messages increased their transmission by approximately 20% per word, compared to purely-moral and purely-emotional language.[12]

See also

References

- Pizarro, David A. (2007). "Moral Emotions". In Baumeister, Roy F; Vohs, Kathleen D (eds.). Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. SAGE Publications, Inc. pp. 588–589. doi:10.4135/9781412956253.n350. ISBN 9781412956253.

- Haidt, Jonathan (2003). "The Moral Emotions" (PDF). In Davidson, Richard; Scherer, Klaus; Goldsmith, H. (eds.). Handbook of Affective Sciences. Oxford University Press. pp. 855. ISBN 978-0-19-512601-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tangney, June Price; Stuewig, Jeff; Mashek, Debra J. (January 2007). "Moral Emotions and Moral Behavior" (PDF). Annual Review of Psychology. 58 (1): 345–372. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145. PMC 3083636. PMID 16953797.

- Kohlberg, Lawrence (1981). The Philosophy of Moral Development. Essays on Moral Developent. 1. San Francisco: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-064760-5. OCLC 7307342.

- Hare, R. M. (1981). Moral Thinking: Its Levels, Method, and Point. Oxford University Press, UK. ISBN 978-0-19-824659-6.

- Gewirth, A. (1984). "Ethics". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 6. Chicago. pp. 976–998.

- Ekman, Paul (May 1, 1992). "An argument for basic emotions" (PDF). Cognition and Emotion. 6 (3–4): 169–200. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.1984. doi:10.1080/02699939208411068. ISSN 0269-9931.

- Batson, C. D.; Klein, T. R.; Highberger, L.; Shaw, L. L. (1995). "Immorality from empathy-induced altruism: When compassion and justice conflict". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 68 (6): 1042–1054. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.6.1042.

- Batson, C. Daniel; Fultz, Jim; Schoenrade, Patricia A. (March 1, 1987). "Distress and Empathy: Two Qualitatively Distinct Vicarious Emotions with Different Motivational Consequences". Journal of Personality. 55 (1): 19–39. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00426.x. ISSN 1467-6494. PMID 3572705.

- Decety, Jean (November 1, 2014). The Neuroevolution of Empathy and Caring for Others: Why It Matters for Morality. Research and Perspectives in Neurosciences. 21. pp. 127–151. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-02904-7_8. ISBN 978-3-319-02903-0.

- Decety, J.; Cowell, J. M. (2014). "The complex relation between morality and empathy" (PDF). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 18 (7): 337–339. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2014.04.008. PMID 24972506.

- Brady, William J.; Wills, Julian A.; Jost, John T.; Tucker, Joshua A.; Bavel, Jay J. Van (2017-07-11). "Emotion shapes the diffusion of moralized content in social networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (28): 7313–7318. doi:10.1073/pnas.1618923114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5514704. PMID 28652356.