Monetary reform in the Soviet Union, 1922–24

The monetary reform of the Soviet Union 1922-1924 was a set of monetary policies implemented in the Soviet Union as a part of the Soviet government’s New Economic Policy. Principal objectives of this reform included the easing the effects of hyperinflation, establishing a unified medium of exchange and the creation of a more independent central bank. [1] In accordance with the economic data recorded in both archives of the Soviet Union[2] and the Russian Federation, the results of the reform were overall mixed; some modern-day economists label the new policies as a successful transition towards state capitalism, while others describe it was problematic and did not uphold the targets laid out within its original blueprint. [3]Economists including Keynes often categorise the reform as an aggregation of short-term monetary expansion experiments which fundamentally defined the intertemporal nature between Soviet monetary and fiscal policies where the state peruses a more active role in dictating the growth of the economy.[4]

New Economic Policy Propaganda | |

| Location | Soviet Union |

|---|---|

| Type | Monetary Policy |

| Cause | Russian Revolution Russian Civil War World War One |

| Organized by | Premier Vladimir Lenin |

| Outcome | Return to the gold pegged monetary system; end of hyperinflation in Soviet Union; stabilization of the Soviet economy |

Introduction of Monetary Reforms (July 1922)

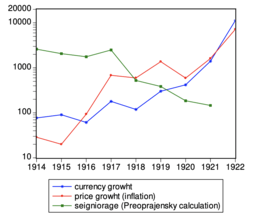

Having to endure a budget deficit since the start of World War I (1914), by the end of the Russian Civil War (1918-1921), the Russian economy was in a state of excessive recession. According to historian Paul Flewers, both the wartime economic policy of War Communism and the communist ideology drift in questioning the long-term necessity of a monetary system triggered a massive increase in the issuance of money which prolonged the continuous rise in the Soviet Union's domestic inflation rate. [5] By 1921, the Soviet economic data archive indicates that the national monthly inflation rate averaged around 50% and the quantity of currency circulation within the Soviet economy increased by 164.20 times.[6] According to the Soviet Union's 1921 purchasing power index 10,000 Soviet sovznaks in 1921 only held the equivalent purchasing power of 0.59 Russian imperial chervonets of 1914. [7]

Beginning of the Reform

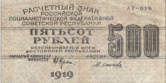

The initial stages of the Soviet Monetary Reform began in July 1922 when the Soviet Central bank, Gosbank, was granted by the Soviet State Planning Committee, Gosplan, with a certain degree of autonomy. [1][6] According to Russian historian, Zahari Atlas, not only was the central bank given the monopoly to issue national banknotes, it also had the power to restrict the government’s access to capital. A more independent central bank also became a natural economic oversight mechanism used in fighting inflation and geared the Soviet economy with the flexibility to counter both domestic and global economic fluctuations. [8] Described by Amy Hewes, direct outcomes from this policy monetary power distribution were the Soviet economy return to the gold standard, introduction of a separate national currency, elimination of the government’s budget deficit and the restoration of a centrally administered legal tax system. By the end of 1922, a dual currency system was in place where gold pegged Russian chervonets were brought back as a unit of account while Soviet printed money, sovznaks, were commissioned as the nationalised medium of exchange and means of payment for the domestic market.[5]

Implementation of the Reform (1922~1923)

By June 1923, Katzenellenbaum’s data figures[9] reveal how the first round of policies surrounding the creation of a more independent central bank has lowered the Soviet government’s fiscal expenditure against the nation’s currency circulation from the 1920s 85% to 1923’s 26.6%.[9] While the nationalised market traded with gold-backed chervonets, the privatised markets operated under the more liquid, government monitored sovznaks. [10] Since chervonets and sovznaks were convertible and foreign trade institutions only accepted chervonets as the means of payment, the dual currency system naturally became a transaction channel connecting the sovznak orientated Soviet economy with the gold pegged international monetary system[11]. In line with historian economist Alexander Gourvitch's analysis, the Soviet dual currency system functioning as a direct monetary transaction channel the Soviet economy reopened to both international exports and imports resulting into both a steady growth in trade surplus and the rapid stabilisation of domestic commodity prices. Liberal Keynesians, including Keynes himself, praised the Soviet monetary reform as “pioneering the foundation of a more progressive monetary system” that effectively incorporates the power of state-led fiscal policies without harming the fundamental flexibility required for a functioning market economy.” [1] In contrast, majority of western economists at that time maintained the position in which any degree of state intervention would make it impossible to maintain long-term growth and the Soviet planned economy was simply not functionable.

Purpose of the Reform

According to both historian Gustavus Tuckerman and economist Yasushi Nakamura, the central theme behind the Soviet monetary reform we stabilisation. A united pursuit to accomplish this goal of stabilisation across both the Soviet Politburo and Central Planning Committee gave rise to a series of monetary experiments which to a great extent contradicted the collective ownership structure that was embodied as a core principle within both the communist manifesto and the Soviet planned economy. Nakamura's catalogue provided a list of government agencies who each independently proposed a collection of monetary policies for the central government to incorporate within the overarching reform.

Introduction of a Dual Currency System

According to the monetary policy proposal list organised by Nikolay Nenovsky; Gosbank, the newly established Soviet central bank, proposed to issue banknotes based on short-term obligations which were backed by gold while Gosplan, the Soviet central planning committee argued for the elimination of the gold standard and encouraged a full transition into a commodity oriented monetary system.[11] More liberal government agencies such as the Ministry for Trade advocated for policies such as the acceptance of loans from foreign banking institutions and the temporary integration into a collection of international monetary systems controlled by foreign central banks. According to Nenovsky, the debate of which policies could be integrated remained in discussion from July 1921 up until November 1922. While stabilisation remained the core goal, Soviet conservative economists represented by the then head of Gosplan Stanislav Strumilin were reluctant to expose too much of the Soviet economy to western institutions, labelling the same institutions which funded the White Russia Movement as "capitalist aggressors" who never stand on the same side as the Soviets. Meanwhile, Strumilin remained supportive of a "socialist commodity exchange," which functioned under the rules of modern-day fiat currency backed monetary systems.

By aggregating all the proposed policies into one, the final formation of the Soviet monetary reform composed of an aggregation of proposed policies where foreign long-term and short-term loans backed by a variety of mineral commodities were accepted but the government-controlled dual currency system remained in place as to protect Soviet monetary sovereignty.[11]

Structure of a Dual Currency System

As a result of the monetary reform, in 1923, a dual currency monetary system composed of chervonets and sovznaks was formally established. Based on the balance sheet data recorded in Gosbank's issue department, while sovznaks were backed by chervonets, 25% of chervonets were backed by a collection of precious metals alongside a reserve of stable foreign currencies pegged to the gold standard. [5] The remaining 75% of chervonets were backed by short-term commodity loans provided by foreign banks. Described by Nenovsky as a "deliberate arrangement" to uphold the Soviet Union's monetary sovereignty, besides playing the role connecting the Soviet economy with the western financial systems, chervonets also acted as a buffer so that foreign banks are not able to directly influence the sovznak orientated Soviet domestic economy. [11] In theory, under an official exchange rate, chervonets and sovznaks were convertible, yet according to Nakamura, "as if deliberately," no clear channel of exchange between the two currencies was established until 1924. As a result, most economic activities conducted within the Soviet Union remained to be in sovznaks.[5]

Issues within the Dual Currency System

In accordance with the Katzenellenbaum’s data figures[9], under the dual currency system, Soviet trade surplus experienced steady growth, generating the required capital reserve used to pay off the short-term foreign loans that backed the value of chervonets. By the end of 1923, all primary monetary debt was paid off and the national current account became positive, indicating the Soviet Union now had complete control over its monetary system.[5] Noted by Keynes, since both chervonets and sovznaks were now under the full control of a single monetary regime a natural rivalry within the dual currency system is inevitable. As the Soviet Union's gold-pegged currency, chervonets naturally held a higher monetary value than government priced sovznaks.

Described by Nenovsky, alike other gold-pegged currencies at the time, chervonets were adaptive to the alteration in market conditions and enjoyed international recognition while the value of sovznaks remained under government scrutiny and this dependency on government control translated to the fact that the tender only had the limited capacity to react to market movements. In a note to the central bank, the Treasurer of the Soviet Union, Grigori Sokolnikov indicated that the value disorientation between the two currencies proved to be a growing problem for the domestic economy and since the government determines the value of sovznaks against the central bank’s supply of chervonets, the dual currency form a dependent relationship which causes monetary disorientation considering the market naturally prefers the more valuable legal tender. As the primary purpose of sovznaks was to function as a "monetary line of defence," under the scenario where the value of chervonets was indirectly controlled by the foreign loans which initially backed 75% of chervonets’ value, the repayment of these loans by the end of 1923 meant this contingency plan was no longer essential. [8] Thus, recorded in the Soviet political archives[2], during the 12th Soviet Congress (1923) the conceptual pursuit for a “peaceful coexistence” between the two currencies was removed, and a gradually monetary shift towards a single currency system began. Soviet literature started labelling chervonets as the “stable currency,” whereas the sovznak was prescribed as “a declining currency.” [4] On the 7th of July 1924, the Soviet Central Executive Committee decided to limit the issue of sovznaks and initiate a controlled elimination of the dual currency system.

A Single Currency Monetary System (1923~1924)

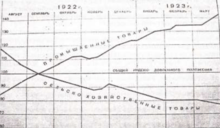

Price Scissors Effect

With the government’s favour leaning towards chervonets yet the Soviet economy largely functioned around sovznaks, the effects of price scissors became more prevalent in the winter of 1923. [10] In accordance with the Katzenellenbaum economic data[9], high industrial prices and low agricultural prices led to an excessive transfer of resources across the sovznak orientated countryside into the chervonet dominated state urban industrialised centres. [7] This price imbalance accelerated the depreciation of sovznaks, and by October 1923, sovznaks, once again began experiencing extreme daily inflation rates up to 4.4%.[10]

Return to a Single Currency System

Although the sovznak orientated Soviet population found it harder to conduct daily transactions, the chervonets dominated government expenditure experienced no shortage of funds and the national balance sheet continued to remain cash-flow positive. State enterprises either have endured minimised losses or in some instances been able to gain a profit. By the end of 1923’s fiscal year, a surplus in the Soviet Union’s current account signified the successful transition into an export-driven economy.[5] According to Soviet archives[2], on the 14th of February 1924, the issue of sovznaks came to a complete halt. Under an exchange rate of 1 gold rouble to 50,000 1923 sovznaks and one gold rouble to 50 billion 1922 sovznaks, the entire circulation of sovznaks within the Soviet economy was bought outright in between 7th of March 1924 to 10th of May 1924. With the formal end to the dual currency system, the Soviet monetary reform of 1922~1924 was complete.[6] As a result, the nation’s currency circulation was optimised and the Soviet chervonet, later defined as the rouble, was once again pegged to gold, the universal storage of value before the adoption of the Bretton-Woods system.[10]

Influence of the Reform

The Soviet Monetary Reform of 1922~1924 was one of the first economic initiatives implemented across the Soviet Union. Liberal economists often describe this reform as the first successful establishment of state capitalism. In contrast, Austrian school economists refer to the reform as Russia’s “jagged return” to a market-orientated economy.[3] As the first communist-led economic reform, the Soviet monetary reform of 1922~1924 demonstrated an ideological shift where the proposal to eliminate money was at first replaced with a dual currency system, and later a stable gold pegged monetary regime. Pioneering along with other components of the New Economic Policy, the Soviet monetary model became a widely adopted exemplar for the late 20th-century economic reforms in nations like China and Vietnam.[5]

References

- Birman, Igor; Clarke, Roger A. (Oct 1985). "Inflation an the money supply in the Soviet economy". Soviet Studies. 37 (4): 494–504. doi:10.1080/09668138508411605. ISSN 0038-5859 – via JSTOR.

- Kragh, Martin; Hedlund, Stefan (2015). "Researching Soviet Archives: An Introduction". The Russian Review. 74 (3): 373–376. doi:10.1111/russ.12020. ISSN 1467-9434.

- Wolverton Jr, Robert E. (2013-10-18). "Electronic Theses and Dissertations". doi:10.4324/9781315877655. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ellman, Michael (Dec 1991). "Convertibility of the rouble". Cambridge Journal of Economics. 15 (4): 481–497. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a035185. ISSN 1464-3545.

- Nakamura, Yasushi. (2017). Monetary policy in the Soviet Union : empirical analyses of monetary aspects of Soviet economic development. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 978-1-137-49418-4. OCLC 1000453406.

- Hewes, Amy (Jun 1922). "The Attitude of the Soviet Government toward Co-Operation". Journal of Political Economy. 30 (3): 412–416. doi:10.1086/253440. ISSN 0022-3808.

- Hoover, Calvin B. (Jun 1930). "The Fate of the New Economic Policy of the Soviet Union". The Economic Journal. 40 (158): 184. doi:10.2307/2223931. ISSN 0013-0133.

- Pickersgill, Joyce E. (Sep 1986). "Hyperinflation and Monetary Reform in the Soviet Union, 1921-26". Journal of Political Economy. 76 (5): 1037–1048. doi:10.1086/259466. ISSN 0022-3808.

- Katzenellenbaum, S. S. (1925). Russian currency and banking 1914-1924. P.S. King and Son. OCLC 912106785.

- Gregory, Paul R. (1982). Russian national income, 1885-1913. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24382-3. OCLC 8034722.

- Nenovsky, Nikolay; Rizopoulos, Yorgos (2005). "Measuring the Institutional Change of the Monetary Regime in a Political Economy Perspective". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.665145. ISSN 1556-5068.