Mlikh

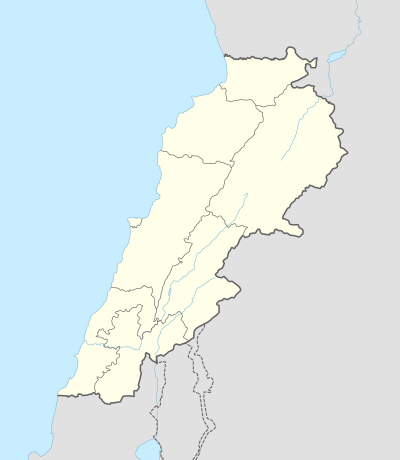

Mlikh (Arabic: مليخ) is a mountain village in the Jezzine district, located in the South Governorate in Southern Lebanon. It lies on the Al Rihan mountain chain (around 4,000-7,000 feet above sea level, Mlikh is located at around 1,280 meters and higher at other peaks above sea level).[1][2][3] The village is located on a number of mountains peaks, and between the mountain peaks.

Mlikh مليخ | |

|---|---|

| |

Mlikh | |

| Coordinates: 33°28′02″N 35°33′13″E | |

| Grid position | 133/170 L |

| Country | |

| Governorate | southGovernorate |

| District | Jezzine District |

Etymology

The word Mlikh may derive from the Semitic (Aramaic) word for "king". The root of Mlikh or king in the Semitic language is mlk. [4] The word malik derives from the Semitic root mlk. [5] Mlikh or mlk may also possibly be connected to Moloch since moloch derives from the same mlk root, and means "to rule". In Phoenician (where it is theorized "mlk" derives from) mlk has been linked to "king", possibly deriving from pagan Melqart.[6][7][8]

Demographics

The natives of Mlikh are Shia and Maronite-Christians.[9] The village houses one church, one mosque, and a Hussainiya.

%2C_Jezzine_District%2C_Nabatieh_Governorate%2C_South_Lebanon%2C_Lebanon%2C_Middle_East%2C_Mediterranean%2C_%D8%A8%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A7%D8%A8%D8%8C_%D9%85%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%AE%D8%8C_%D8%AC%D9%86%D9%88%D8%A8_%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%86.jpg)

Historical significance

The village is home to a number of ancient "prophets" whose tombs are located on the mountain peaks surrounding Mlikh, including Burkab, and Sujud (believed by some scholars to be Oholiab, however his existence or this connection cannot be fully verified).[10][11][12] Shia and Christian inhabitants of the village and of the southern Lebanese region make pilgrimages to the tombs.[10][13]

Notable people

Amal Abou Zeid (born 5 June 1953) is a member of the Lebanese parliament, and is from Mlikh. He is a member of the National Commission for Economy, Trade, Industry and Planning in the Lebanese Parliament, since December 2016.

References

- A Dictionary of the Bible: Kir-Pleiades. Scribner. 1902. p. 91.

- https://www.localiban.org/article4208.html

- http://www.fallingrain.com/world/LE/06/Mlikh.html

- Bill T. Arnold; H. G. M. Williamson (26 October 2011). Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books. InterVarsity Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-8308-6946-6.

- J. Hoftijzer and K. Jongenling, Dictionary of the North-West Semitic Inscriptions, (Brill, Leiden, 1995) p.635

- Heinrich W. Guggenheimer (23 April 2010). Tractates Sanhedrin, Makkot, and Horaiot. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-3-11-021961-6.

- Josephine Quinn (11 December 2017). In Search of the Phoenicians. Princeton University Press. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-1-4008-8911-2.

- Francesca Stavrakopoulou (2004). King Manasseh and Child Sacrifice: Biblical Distortions of Historical Realities. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 215–. ISBN 978-3-11-017994-1.

- مفرّج، طوني (2002). موسوعة قرى صمدن لبنان. نوبليس،.

- Cyrus Schayegh; Andrew Arsan (5 June 2015). The Routledge Handbook of the History of the Middle East Mandates. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-49706-6.

- Eli Yassif (1986). Jewish Folklore: An Annotated Bibliography. Garland. ISBN 978-0-8240-9039-5.

- Henry Stafford Osborn (1860). The pilgrim in the Holy-land; or, Palestine, past and present.

- Southern Folklore Quarterly. University of Florida. 1948.