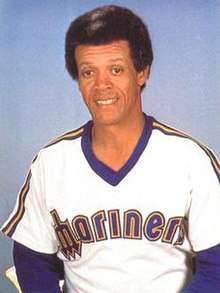

Maury Wills

Maurice Morning Wills (born October 2, 1932) is an American former professional baseball player and manager. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) primarily for the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1959 through 1966 and the latter part of 1969 through 1972 as a shortstop and switch-hitter; he played for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1967 and 1968, and the Montreal Expos the first part of 1969. Wills was an essential component of the Dodgers' championship teams in the mid-1960s, and is credited for reviving the stolen base as part of baseball strategy.[1]

| Maury Wills | |||

|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) Wills during Spring Training in 2009 | |||

| Shortstop / Manager | |||

| Born: October 2, 1932 Washington, D.C. | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| June 6, 1959, for the Los Angeles Dodgers | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| October 4, 1972, for the Los Angeles Dodgers | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .281 | ||

| Hits | 2,134 | ||

| Home runs | 20 | ||

| Runs batted in | 458 | ||

| Stolen bases | 586 | ||

| Managerial record | 26–56 | ||

| Winning % | .317 | ||

| Teams | |||

As player

As manager | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

Wills was the National League Most Valuable Player (MVP) in 1962, stealing a record 104 bases to break the old modern era mark of 96, set by Ty Cobb in 1915. He was an All-Star for five seasons and seven All-Star Games[2], and was the first MLB All-Star Game Most Valuable Player in 1962. He also won Gold Gloves in 1961 and 1962. In a fourteen-year career, Wills batted .281 with 20 home runs, 458 runs batted in, 2,134 hits, 1,067 runs, 177 doubles, 71 triples, 586 stolen bases and 552 bases on balls in 1,942 games. Since 2009, Wills is a member of the Los Angeles Dodgers organization serving as a representative of the Dodgers Legend Bureau.

In 2014, Wills appeared for the first time as a candidate on the National Baseball Hall of Fame's Golden Era Committee election ballot[3] for possible Hall of Fame consideration in 2015 which required 12 votes. Wills missed getting elected by 3 votes.[4] All the other candidates on the ballot also missed being elected. The Committee meets and votes on ten selected candidates from the 1947 to 1972 era every three years.[5]

Early life

Wills was born in Washington, D.C. Maurice, or Sonny as he was called at Cardozo Senior High School in Washington, first showed up as an All City pitcher in the local Washington Daily News. He played on Sal Hall's undefeated '48 Cardozo football team that never had any points scored against them. In the '49–'50 school year, three-sport standout Sonny Wills was named an All City football quarterback, basketball player, and baseball pitcher. On May 8, 1950, in a game against Phelps, Wills threw a one-hitter and struck out seventeen.

MLB career

Los Angeles Dodgers

Wills began his major league career in 1959 and played in 83 games for the Los Angeles Dodgers. In the 1959 World Series, he played in each of the six games, hitting 5-for-20 with one stolen base and two runs in the Dodger victory. In Wills' first-full season in 1960, he hit .295 and led the league with 50 stolen bases, being the first National League player to steal 50 bases since Max Carey stole 51 in 1923. In 1962, Wills stole 104 bases to set a new MLB stolen base record, breaking the old modern era mark of 96, set by Ty Cobb in 1915.[6] Wills also stole more bases than all of the other teams that year, the highest total being the Washington Senators' 99. Wills success in base stealing that year led to another remarkable statistic, he was caught stealing just 13 times all season. He hit .299 for the season, led the NL with 10 triples and 179 singles, and was selected the NL Most Valuable Player over Willie Mays (Mays hit .304 with 49 home runs and 141 runs batted in) by seven points. Not until Barry Larkin in 1995 would another shortstop win a National League Most Valuable Player Award. Late in that record-setting 1962 season, San Francisco Giants Manager Alvin Dark ordered grounds crews to water down the base paths, turning them into mud to hinder Wills' base-stealing attempts. Wills played a full 162 game schedule, plus all three games of the best of three regular season playoff series with the Giants, giving him a total of 165 games played, an MLB record that still stands for most games played in a single season. His 104 steals remained a Major League record for switch-hitters until 1985, when Vince Coleman eclipsed the mark with 110. In the 1963 World Series, he went 2-for-16 for a .133 batting average with one stolen base. In the 1965 World Series, he played in all seven games and went 11-for-30 with three runs and three stolen bases in a hard-fought Dodger victory, his third and last World Series title.

.jpg)

While playing for the Dodgers, Wills was a Gold Glove Award winner in 1961 and 1962, and was named a NL All-Star five times (5 seasons); selected seven times for the All-Star Game (2 games were played in 1961 and 1962).

In the 1966 World Series, he went 1-for-13 with one stolen base on a .077 batting average as the Dodgers were swept in four games. Following the 1966 season, in which he dropped to 38 stolen bases and was caught stealing 24 times, the Dodgers traded Wills to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Bob Bailey and Gene Michael.[7]

Pittsburgh Pirates

On December 1, 1966, he was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Bob Bailey and Gene Michael. In the 1967 season, he played in 149 games while having 186 hits, 29 stolen bases (his lowest since having 35 in 1961) and 45 RBIs for a .302 batting average. In the following season, he played in 153 games, getting 174 hits, 31 RBIs and 52 stolen bases, although he was caught stealing 21 times, with a .278 batting average.

Montreal Expos

On October 14, 1968, he was drafted by the Montreal Expos from the Pirates as the 21st pick in the expansion draft. Wills batted first in the lineup for the inaugural game of the Expos on April 8, 1969. He went 3-for-6 with one RBI and one stolen base in the 11-10 win.[8] He would play just 47 games for the team, getting 42 hits and 15 stolen bases on a .222 batting average. On June 11, he was traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers along with Manny Mota to the Los Angeles Dodgers for Ron Fairly and Paul Popovich.

Back to the Dodgers

In 104 games, he hit safely 129 times while stealing 25 bases for a .297 batting average. He was 11th in MVP voting that year. In the following year, he played in 132 games while having 141 hits and 28 stolen bases on a .270 batting average. For 1971, he played in 149 games while having 169 hits, 15 stolen bases and a .281 batting average, although he finished 6th in MVP voting. 1972 was his final season, and Wills played 71 games for 17 hits and one stolen base and a .129 batting average. In his final appearance on October 4, 1972, he served as a pinch runner for Ron Cey in the top of the ninth inning, scoring a run on a home-run by Steve Yeager while also playing the bottom of the ninth inning at third base.[9] On October 24, 1972, he was released by the Dodgers.

Base stealing

Although Chicago White Sox shortstop Luis Aparicio had been stealing 50+ bases in the American League for several years prior to Wills' insurgence, Wills brought new prominence to the tactic.[10] Perhaps this was due to greater media exposure in Los Angeles, or to the Dodgers' greater success, or to their extreme reliance on a low-scoring strategy that emphasized pitching, defense, and Wills' speed to compensate for their lack of productive hitters. Wills was a significant distraction to the pitcher even if he didn't try to steal, because he was a constant threat to do so.[11] The fans at Dodger Stadium would chant, "Go! Go! Go, Maury, Go!" any time he got on base.[12] While not the fastest runner in the major leagues, Wills accelerated with remarkable speed. He also studied pitchers relentlessly, watching their pick-off moves even when not on base. And when driven back to the bag, his fierce competitiveness made him determined to steal. Once when on first base against New York Mets pitcher Roger Craig, Wills drew twelve consecutive throws from Craig to the Mets first baseman. On Craig's next pitch to the plate, Wills stole second.

In the wake of his record-breaking season, Wills' stolen base totals dropped precipitously. Though he continued to frighten pitchers once on base, he stole only 40 bases in 1963 and 53 bases in 1964. In 1965, Wills set out on a pace to break his own record. By the time of the All-Star Game in July, he was 19 games ahead of his 1962 pace. However, Wills at age 32, began to slow in the second half. The punishment of sliding led him to bandage his legs before every game, and he ended the 1965 season with 94 stolen bases which was the second highest in National League history at that time.

Managing and retirement

After retiring, Wills spent time as a baseball analyst at NBC from 1973 through 1977. He also managed in the Mexican Pacific League—a winter league—for four seasons, during which time he led the Naranjeros de Hermosillo to the 1970–71 season league championship.[13] Wills let it be known he felt qualified to pilot a big-league club. In his book, How To Steal A Pennant, Wills claimed he could take any last-place club and make them champions within four years. The San Francisco Giants allegedly offered him a one-year deal, but Wills turned them down. Finally, in 1980, the Seattle Mariners fired Darrell Johnson and gave Wills the reins.

Baseball writer Rob Neyer, in his Big Book of Baseball Blunders, criticized Wills for "the variety and frequency of [his] mistakes" as manager, calling them "unparalleled." In a short interview appearing in the June 5, 2006 issue of Newsweek, Neyer said, "It wasn't just that Wills couldn't do the in-game stuff. Wills's inability to communicate with his players really sets him apart. He said he was going to make his second baseman, Julio Cruz, his permanent shortstop. Twenty-four hours later he was back at second base. As far as a guy who put in some real time (as a manager), I don't think there's been anyone close to Wills."

According to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer's Steve Rudman, Wills made a number of gaffes. He called for a relief pitcher although there was nobody warming up in the bullpen, held up another game for 10 minutes while looking for a pinch-hitter and even left a spring-training game in the sixth inning to fly to California.

The most celebrated incident of Wills' tenure as manager occurred on April 25, 1981. He ordered the Mariners' grounds crew to make the batter's boxes one foot longer than regulation. The extra foot was in the direction of the mound. However, Oakland Athletics manager Billy Martin noticed something was amiss and asked plate umpire Bill Kunkel to investigate. Under questioning from Kunkel, the Mariners' head groundskeeper admitted Wills had ordered the change. Wills claimed he was trying to help his players stay in the box. However, Martin suspected that given the large number of breaking-ball pitchers on the A's staff, Wills wanted to give his players an advantage. The American League suspended Wills for two games and fined him $500. American League umpiring supervisor Dick Butler likened Wills' actions to setting the bases 88 feet apart instead of 90 feet.[14]

After leading Seattle to a 20-38 mark to end the 1980 season, new owner George Argyros fired Wills on May 6, 1981 with the M's deep in last place at 6-18. This gave him a career record of 26-56 for a winning percentage of .317, one of the worst ever for a non-interim manager. Years later, Wills admitted he probably should have gotten some seasoning as a minor-league manager prior to being hired in Seattle.

However, the aforementioned Julio Cruz, himself an accomplished base stealer, credited Wills for teaching him how to steal second base against a left-handed pitcher. Dave Roberts, who stole second base and then scored for the Boston Red Sox when facing elimination in Game 4 of the 2004 ALCS, similarly credits Wills for coaching him to steal under pressure circumstances. "He said, 'DR, one of these days you're going to have to steal an important base when everyone in the ballpark knows you're gonna steal, but you've got to steal that base and you can't be afraid to steal that base.' So, just kind of trotting out on to the field that night, I was thinking about him. So he was on one side telling me 'this was your opportunity'. And the other side of my brain is saying, 'You're going to get thrown out, don't get thrown out.' Fortunately Maury's voice won out in my head." [15]

The Maury Wills Museum is in Fargo, North Dakota at Newman Outdoor Field, home of the Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks. Wills was a coach on the team from 1996 to 1997 and currently serves as a radio color commentator for the RedHawks on KNFL "740 The Fan" with play-by-play announcer Jack Michaels.

Music career

Throughout most of his major league playing career, Wills supplemented his salary in the off-season by performing extensively as a vocalist and instrumentalist (on banjo, guitar and ukelele), appearing occasionally on television and frequently in night clubs.[16] He also cut at least two records during this period—one under his own name,[17] the other as featured vocalist with Lionel Hampton.[18] For roughly two years, starting on October 24, 1968, Wills was the co-owner, operator and featured performer of a new nightclub, The Stolen Base (aka Maury Wills' Stolen Base), located in Pittsburgh's Golden Triangle and offering a mix of "banjos, draft beer and baseball."[19][20][21]

By no account, least of all his own, was Wills a consummate virtuoso; "good; not great, maybe, but good," wrote Newsday's Stan Isaacs, reviewing a 1966 Basin Street East engagement shared with World Series nemesis Mudcat Grant (although Isaacs did single out "a few mean choruses on banjo").[22] Nonetheless, the level of proficiency attained on Wills' principal instrument was attested to on two separate occasions by the American Federation of Musicians: first, in December 1962, when the president of Los Angeles Local 47, after hearing just a few minutes of banjo playing, promptly waived the balance of Wills' membership entrance exam,[23] and then, just over five years later, when trumpeter Charlie Teagarden, specifically citing "Maury's banjo-playing ability" (and evidently unaware of Wills' already established membership), "presented him, on behalf of the musicians union, an honorary lifetime membership."[24]

Personal life

After receiving the Hickok Belt in 1962, Wills was determined by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue for having deficiencies in reported income and awards deductions. The United States Tax Court supported the Commissioner and the tax case was brought up to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit where the decision was subsequently affirmed by it.

In his autobiography, On the Run: The Never Dull and Often Shocking Life of Maury Wills, Wills claimed to have had a love affair with actress Doris Day. Day denied this in her autobiography Doris Day: Her Own Story, where she said it was probably advanced by the Dodgers organization for publicity purposes.

Wills was well known as an abuser of alcohol and cocaine until getting sober in 1989.[25] In December 1983, Wills was arrested for cocaine possession after his former girlfriend, Judy Aldrich, had reported her car had been stolen. During a search of the car, police found a vial allegedly containing .06 grams of cocaine and a water pipe. The charge was dismissed three months later on the grounds of insufficient evidence.[26]

The Dodgers organization paid for a drug treatment program, but Wills walked out and continued to use drugs until he began a relationship with Angela George, who encouraged him to begin a vitamin therapy program. The two later married.[27]

In his New Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James is highly critical of Wills as a person, but still ranked him as the #19 shortstop of all time.

Maury Wills is the father of former major leaguer Bump Wills, who played for the Texas Rangers and Chicago Cubs for six seasons. The two had a falling out following the publication of Maury's autobiography in 1991, involving a salacious anecdote, but now occasionally speak.[28]

In 2009, Wills was honored by the city of Washington, D.C. and Cardozo Senior High School with the naming of the former Banneker Recreation Field in his honor.[29] The field was completely renovated and serves as Cardozo's home diamond.

MLB awards, achievements, records

Awards

- MLB All-Star Game MVP (1962)

- NL MVP: 1962

- NL Gold Glove (1961, 1962)

Achievements

- NL All-Star[30] (1961–63, 1965–66)

- NL leader in At Bats (1961, 1962)

- NL leader in Triples (1962)

- NL leader in Stolen Bases (1960–65)

- NL leader in Singles (1961–62, 1965, 1967)

- NL leader in Sacrifice Hits (1961)

- Los Angeles Dodgers Career Stolen Base leader (490)

Records

- Most Games Played in a single season (165 in 1962)

- 7th player to hit home runs from each side of the plate in a game (1962)

- Stole 104 bases in 1962, still an MLB-record among switch-hitters

- Los Angeles Dodgers Career Stolen Bases (490)

- Los Angeles Dodgers Single-Season at Bats (695 in 1962)

Other awards

- Hickok Belt Award (1962)

- The Baseball Reliquary's Shrine of the Eternals (class of 2011).[31]

The stolen base "asterisk"

While Wills had broken Cobb's single season stolen base record in 1962, the National League had increased its number of games played per team that year from 154 to 162. Wills' 97th stolen base had occurred after his team had played its 154th game; as a result, Commissioner Ford Frick ruled that Wills' 104-steal season and Cobb's 96-steal season of 1915 were separate records, just as he had the year before (the American League had also increased its number of games played per team to 162) after Roger Maris had broken Babe Ruth's single season home run record. Both stolen base records would be broken in 1974 by Lou Brock's 118 steals; Brock had broken Cobb's stolen base record by stealing his 97th base before his St. Louis Cardinals had completed their 154th game.

See also

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball stolen base records

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual stolen base leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

References

- "They Were There 1962: Maury Wills". Thisgreatgame.com. 2010. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- MLB held two All-Star Games from 1959 through 1962.

- "Golden Era Committee Candidates Announced". baseballhall.org. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- "Golden Era Committee Announces Results". National Baseball Hall of Fame. December 8, 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- Bloom, Barry M. (December 8, 2014). "No one elected to Hall of Fame by Golden Era Committee". MLB.com. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- "Maury Wills Baseball's Greatest Base Stealer". The Washington Afro American. September 25, 1962.

- "The Morning Record - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYN/NYN196904080.shtml

- https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/ATL/ATL197210040.shtml

- Castle, George (2016). Baseball's Game Changers: Icons, Record Breakers, Scandals, Sensational Series and More. Guilford, Connecticut : Lyons Press, an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield. p. 115. ISBN 9781493019465.

- Walfoort, Cleon (March 1961). "Bases Are for Running". Boys' Life. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- Castle (2016). "Baseball's Game Changers..." p. 117.

- "Naranjeros de Hermosillo". Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- Zumsteg, Derek (2007). The Cheater's Guide to Baseball. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 265. ISBN 9780618551132.

- Roberts' steal set amazing 2004 playoff run in motion https://www.mlb.com/news/dave-roberts-steal-set-amazing-2004-red-sox-playoff-run-in-motion/c-98844328

- "Entertaining Athletes: Negro Sports Stars Augment Salaries by Performing in Night Clubs". Ebony. September 1965. Retrieved October 10, 2018. See also:

- "Maury Wills Makes Hit in Television Performance". Jet. October 24, 1963.

- Du Brow, Rick (UPI). "TV in Review". The Desert Sun. October 7, 1965.

- "Royal Tahitian Books Wills". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. November 15, 1965.

- Koppett, Leonard. "Off Season, A Club Replaces a Bat: Mudcat and Maury of World Series Fame Cavort at Cabaret". The New York Times. January 14, 1966.

- AP. "Wills, Banjo in Tokyo for 11-Day Stand". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. February 25, 1966.

- Duke, Forrest. "Las Vegas Scene: Maury Wills Opens in January". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. November 23, 1967.

- Duke, Forrest. "Las Vegas Scene: Movie Being" Filmed at Hotel Riviera". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. December 5, 1968.

- Duke, Forrest. "Las Vegas Scene: Friends Rally to Aid Showgirl". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. November 26, 1969.

- "Dot Records proudly presents Hot New Single Releases!". Billboard. September 14, 1963. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Maury Wills - Crawdad Hole / Bye-Bye Blues - Glad-Hamp - USA - GH 2009". 45cat.com. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "Grand Opening: The Stolen Base". The Pittsburgh Press. October 24, 1968. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Litman, Lenny. "Maury Wills Hits Home Run in Bow as Pitt Nitery Op." Variety. Oct 30, 1968.

- "The Stolen Base Sale Considered". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. October 3, 1970. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Isaacs, Stan. "Maury and Mudcat: They're Too Much". Newsday. January 17, 1966. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- "Dodgers' Maury Wills Plunks Down for AFM". Variety. December 26, 1962. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Duke, Forrest. "Las Vegas Scene: $80 Million Hotel Complex Set". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. February 11, 1968. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- Streeter, Kurt (August 18, 2008). "Getting Away Clean". Retrieved May 23, 2017 – via LA Times.

- "Lewiston Morning Tribune - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- "The Windsor Star - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1104369/index.htm

- "Maury Wills Field to be dedicated in Washington, D.C." Los Angeles Dodgers. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- MLB held two All-Star Games from 1959 through 1962.

- "Shrine of the Eternals – Inductees". Baseball Reliquary. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

Further reading

- "Maury Wills Set to Play Banjo at Dinner". Los Angeles Times. March 16, 1962.

- Reichler, Joe (AP) "Wills of Dodgers Man of Many Accomplishments; Trains Dog, Plays Banjo, Etc.". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. June 1, 1962.

- "Dodgers' Maury Wills Plunks Down for AFM". Variety. December 26, 1962.

- "Miltie & Maury". Jet. January 10, 1963.

- Thomas, Bob (AP). "Signing Autographs an Art Too, Says Base-Thief Maury Wills". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. October 2, 1963.

- "Dot Records proudly presents Hot New Single Releases!". Billboard. September 14, 1963.

- "Maury Wills Makes Hit in Television Performance". Jet. October 24, 1963.

- "Entertaining Athletes: Negro Sports Stars Augment Salaries by Performing in Night Clubs". Ebony. September 1965.

- Du Brow, Rick (UPI). "TV in Review". The Desert Sun. October 7, 1965.

- Rathet, Mike (AP). "With a Banjo on his Knee". Santa Cruz Sentinel. October 13, 1965.

- Myers, Bob (AP). "Koufax Receives Escort from Cheering LA Fans". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. October 16, 1965.

- "Royal Tahitian Books Wills". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. November 15, 1965.

- UPI. "Wills Holding Out for $100,000; Wanted at Vero Breach, Feb. 27". The Desert Sun. February 18, 1966.

- AP. "Wills, Banjo in Tokyo for 11-Day Stand". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. February 25, 1966.

- UPI. "Walkout May Have Ended Wills' Career with LA". The Madera Daily News-Tribune. November 17, 1966.

- Biederman, Les. "The Scoreboard: Wills Leads Two Lives With Bucs". The Pittsburgh Press. April 18, 1967.

- Eck, Frank. "Maury Wills Trade Saved Dodgers Morale". Santa Cruz Sentinel. April 19, 1967.

- Leonard, Vince. "When a Veteran Is a Rookie: That's Maury on Camera". The Pittsburgh Press. April 20, 1967.

- Leonard, Vince. "Name's the Same on Both Fronts: Wills, Baseballer and Broadcaster". The Pittsburgh Press. April 21, 1967.

- Duke, Forrest. "Las Vegas Scene: Maury Wills Opens in January". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. November 23, 1967.

- Duke, Forrest. "Las Vegas Scene: $80 Million Hotel Complex Set". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. February 11, 1968.

- "Maury Wills Opening 'Stolen Base' Tavern". The Pittsburgh Press. September 22, 1968.

- Abrams, Al. "Sidelight on Sports: Maury Wills Undecided". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. October 24, 1968.

- "Grand Opening: The Stolen Base". The Pittsburgh Press. October 24, 1968.

- Litman, Lenny. "Maury Wills Hits Home Run in Bow as Pitt Nitery Op." Variety. Oct 30, 1968.

- Duke, Forrest. "Las Vegas Scene: Movie Being" Filmed at Hotel Riviera". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. December 5, 1968.

- Feeney, Charley. "Roamin' Around: The Wills Way". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. January 8, 1969.

- Duke, Forrest. "Las Vegas Scene: Friends Rally to Aid Showgirl". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. November 26, 1969.

- Livingston, Pat. "Sports Beat: Strumming on the Old Banjo". The Pittsburgh Press. January 29, 1970.

- Duke, Forrest. "Las Vegas Scene: Jurors Get Kiss After Verdict". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. August 13, 1970.

- Boal, Pete. "Sports Wash: Alston Seems Out of Touch; Mantle Heads All-Villain List; Wrong Place to Break in Wills". San Bernardino Sun-Telegram. March 15, 1973.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maury Wills. |

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Official website

- Baseball Hall of Fame: Wills' Speed Ushered In New Baseball Era

- 2007 Baseball Hall of Fame candidate profile at the Wayback Machine (archived April 23, 2007)

- Maury Wills Museum

- Image of Walt Alston presenting Maury Wills with a Dodger uniform, 1969. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

| Preceded by Ty Cobb |

Major League Baseball single season stolen base record holder 1962–1974 |

Succeeded by Lou Brock |