Marine fungi

Marine fungi are species of fungi that live in marine or estuarine environments. They are not a taxonomic group, but share a common habitat. Obligate marine fungi grow exclusively in the marine habitat while wholly or sporadically submerged in sea water. Facultative marine fungi normally occupy terrestrial or freshwater habitats, but are capable of living or even sporulating in a marine habitat. About 444 species of marine fungi have been described, including seven genera and ten species of basidiomycetes, and 177 genera and 360 species of ascomycetes. The remainder of the marine fungi are chytrids and mitosporic or asexual fungi.[2] Many species of marine fungi are known only from spores and it is likely a large number of species have yet to be discovered.[3] In fact, it is thought that less than 1% of all marine fungal species have been described, due to difficulty in targeting marine fungal DNA and difficulties that arise in attempting to grow cultures of marine fungi.[4] It is impracticable to culture many of these fungi, but their nature can be investigated by examining seawater samples and undertaking rDNA analysis of the fungal material found.[3]

| Part of a series of overviews on |

| Marine life |

|---|

|

|

Different marine habitats support very different fungal communities. Fungi can be found in niches ranging from ocean depths and coastal waters to mangrove swamps and estuaries with low salinity levels.[5] Marine fungi can be saprobic or parasitic on animals, saprobic or parasitic on algae, saprobic on plants or saprobic on dead wood.[2]

Types of marine fungi

Factors that influence whether or not marine fungi are present in any particular location include the water temperature, its salinity, the water movement, the presence of suitable substrates for colonization, the presence of propagules in the water, interspecific competition, pollution and the oxygen content of the water.[5]

Some marine fungi which have ventured into the sea from terrestrial habitats include species that burrow into sand grains, living in the pores. Others live inside stony corals, and may become pathogenic if the coral is stressed by rising sea temperatures.[3][7]

In 2011 the phylogeny of marine fungi was elucidated by analysis of their small subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Thirty six new marine lineages were found, the majority of which were chytrids but also some filamentous and multicellular fungi. The majority of the species found were ascomycetous and basidiomycetous yeasts.[8]

The secondary metabolites produced by marine fungi have high potential for use in biotechnological, medical and industrial applications.[9]

Mangroves

The greatest number of known species of marine fungi are from mangrove swamps.[2] In one study, blocks of mangrove wood and pieces of driftwood of Avicennia alba, Bruguiera cylindrica and Rhizophora apiculata were examined to identify the lignicolous (wood-decaying) fungi they hosted. Also tested were Nypa fruticans, a mangrove palm and Acanthus ilicifolius, a plant often associated with mangroves. Each material was found to have its own characteristic fungi, the greatest diversity being among those growing on the mangrove palm. It was surmised that this was because the salinity was lower in the estuaries and creeks where Nypa grew, and so it required a lesser degree of adaptation for the fungi to flourish there. Some of these species were closely related to fungi on terrestrial palms. Other studies have shown that driftwood hosts more species of fungus than do exposed test blocks of wood of a similar kind. The mangrove leaf litter also supported a large fungal community which was different from that on the wood and living material. However, few of these were multicellular, higher marine fungi.[5]

Other plants

The sea snail Littoraria irrorata damages plants of Spartina in the sea marshes where it lives, which enables spores of intertidal ascomycetous fungi to colonise the plant. The snail eats the fungal growth in preference to the grass itself. This mutualism between the snail and the fungus is considered to be the first example of husbandry among invertebrate animals outside the class Insecta.[10]

Eelgrass, Zostera marina, is sometimes affected by seagrass wasting disease. The primary cause of this seems to be pathogenic strains of the protist Labyrinthula zosterae, but it is thought that fungal pathogens also contribute and may predispose the eelgrass to disease.[11][12]

Wood

Many marine fungi are very specific as to which species of floating and submerged wood they colonise. A range of species of fungi colonise beech while oak supports a different community. When a fungal propagule lands on a suitable piece of wood, it will grow if no other fungi are present. If the wood is already colonised by another fungal species, growth will depend on whether that fungus produces antifungal chemicals and whether the new arrival can resist them. The chemical properties of colonizing fungi also affect the animal communities that graze on them: in one study, when hyphae from five different species of marine fungi were fed to nematodes, one species supported less than half the number of nematodes per mg of hyphae than did the others.[13]

Detection of fungi in wood may involve incubation at a suitable temperature in a suitable water medium for a period of six months to upward of eighteen months.[13]

Algae

Rhyzophydium littoreum is a marine chytrid, a primitive fungus that infects green algae in estuaries. It obtains nutrients from the host alga and produces swimming zoospores that must survive in open water, a low nutrient environment, until a new host is encountered.[13]

Another fungus, Ascochyta salicorniae, found growing on seaweed is being investigated for its action against malaria,[14] a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals.

Lichens

Lichens are mutualistic associations between fungi, usually an ascomycete with a basidiomycete,[15] and an alga or a cyanobacterium. Several lichens, including Arthopyrenia halodytes, Pharcidia laminariicola, Pharcidia rhachiana and Turgidosculum ulvae, are found in marine environments.[2] Many more occur in the splash zone, where they occupy different vertical zones depending on how tolerant they are to submersion.[16] Fossil marine lichens 600 million years old have been discovered in the late Neoproterozoic marine phosphate rocks in the sedimentary, fossil-rich Doushantuo Formation in China.[17]

Vertebrates

Whales, porpoises and dolphins are susceptible to fungal diseases but these have been little researched in the field. Mortalities from fungal disease have been reported in captive killer whales; it is thought that stress due to captive conditions may have been predisposing. Transmission among animals in the open sea may naturally limit the spread of fungal diseases. Infectious fungi known from killer whales include Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans and Saksenaea vasiformis. Fungal infections in other cetaceans include Coccidioides immitis, Cryptococcus neoformans, Loboa loboi, Rhizopus sp., Aspergillus flavus, Blastomyces dermatitidus, Cladophialophora bantiana, Histoplasma capsulatum, Mucor sp., Sporothrix schenckii and Trichophyton sp.[18]

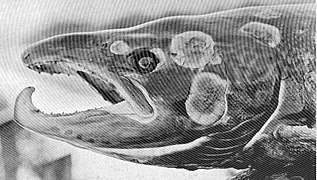

Salmonids farmed in cages in marine environments may be affected by a number of different fungal infections. Exophiala salmonis causes an infection in which growth of hyphae in the kidneys causes swelling of the abdomen. A cellular response by the fish aims to isolate the fungus by walling it off. Fish are also susceptible to fungus-like oomycetes including Branchiomyces which affects the gills of various fishes, and Saprolegnia which attacks damaged tissue.[19]

Invertebrates

The American lobster (Homarus americanus), like many other marine crustaceans, incubates its eggs beneath its tail segments. Here they are exposed to water-borne micro-organisms including fungi during their long period of development. The lobster has a symbiotic relationship with a gram-negative bacterium that has anti-fungal properties. This bacterium grows over the eggs and protects them from infection by the pathogenic fungus-like oomycete Lagenidium callinectes. The metabolite produced by the bacterium is tyrosol, a 4-hydroxyphenethyl alcohol, an antibiotic substance also produced by some terrestrial fungi. Similarly, a shrimp found in estuaries, Palaemon macrodactylis, has a symbiotic bacterium that produces 2,3-indolenedione, a substance that is also toxic to the oomycete Lagenidium callinectes.[20]

Marine Sediment

Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Chytridiomycota have been observed in sediments ranging in depth from 0 to 1740 meters beneath the ocean floor. One study analyzed subsurface samples of marine sediment between these depths and isolated all observable fungi. Isolates showed that most subsurface fungal diversity was found between depths of 0 to 25 meters below the sea floor with Fusarium oxysporum and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa being the most prominent. Overall, the ascomycota are the dominant subsurface phylum.[21] Almost all fungal species recovered have also been observed in terrestrial sediments with spore-sourcing indicating terrestrial origin.[21][22]

Contrary to previous beliefs, deep subsurface marine fungi actively grow and germinate, with some studies showing increased growth rates under high hydrostatic pressures. Though the methods by which marine fungi are able to survive the extreme conditions of the seafloor and below is largely unknown, Saccharomyces cerevisiae shines some light onto adaptations that make it possible. This fungus strengthens its outer membrane in order to endure higher hydrostatic pressures.[21]

Several sediment-dwelling marine fungi are involved in biogeochemical processes. Fusarium oxysporum and Fusarium solani are denitrifiers both in marine and terrestrial environments.[21][23] Some are co-denitrifying, fixing nitrogen into nitrous oxide and dinitrogen.[22] Still others process organic matter including carbohydrate, proteins, and lipids. Ocean crust fungi, like those found around hydrothermal vents, decompose organic matter, and play various roles in manganese and arsenic cycling.[24]

Sediment-bound marine fungi played a major role in breaking down oil spilled from the Deepwater Horizons disaster in 2010. Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Fusarium species, among others, can degrade high-molecular-weight hydrocarbons as well as assist hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria.[24]

Arctic Marine Fungi

Marine fungi have been observed as far north as the Arctic Ocean. Chytridiomycota, the dominant parasitic fungal organism in Arctic waters, take advantage of phytoplankton blooms in brine channels caused by warming temperatures and increased light penetration through the ice. These fungi parasitize diatoms, thereby controlling algal blooms and recycling carbon back into the microbial food web. Arctic blooms also provide conducive environments for other parasitic fungi. Light levels and seasonal factors, such as temperature and salinity, also control chytrid activity independently of phytoplankton populations. During periods of low temperatures and phytoplankton levels, Aureobasidium and Cladosporium populations overtake those of chytrids within the brine channels.[25]

Medical Applications

Marine fungi produce antiviral and antibacterial compounds as metabolites with upwards of 1000 having realized and potential uses as anticancer, anti-diabetic, and anti-inflammatory drugs.[26][27]

Antiviral

The antiviral properties of marine fungi were realized in 1988 after their compounds were used to successfully treat the H1N1 flu virus. In addition to H1N1, antiviral compounds isolated from marine fungi have been shown to have virucidal effects on HIV, herpes simplex 1 and 2, Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus, and Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Most of these antiviral metabolites were isolated from species of Aspergillus, Penicillium, Cladosporium, Stachybotrys, and Neosartorya. These metabolites inhibit the virus’s ability to replicate, thereby slowing infections.[26]

Antibacterial

Mangrove-associated fungi have prominent antibacterial effects on several common pathogenic human bacteria including, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. High competition between organisms within mangrove niches lead to increases in antibacterial substances produced by these fungi as defensive agents.[28] Penicillium and Aspergillus species are the largest producers of antibacterial compounds among the marine fungi.[29]

Anti-cancer

Various deep-sea marine fungi species have recently been shown to produce anti-cancer metabolites. One study uncovered 199 novel cytotoxic compounds with anticancer potential. In addition to cytotoxic metabolites, these compounds have structures capable of disrupting cancer-activated telomerases via DNA binding. Others inhibit the topoisomerase enzyme from continuing to aid in the repair and replication of cancer cells.[27]

See also

References

- Gutiérrez, Marcelo H.; Jara, Ana M.; Pantoja, Silvio (May 2016). "Fungal parasites infect marine diatoms in the upwelling ecosystem of the Humboldt current system off central Chile". Environmental Microbiology. 18 (5): 1646–1653. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13257. PMID 26914416.

- Species of Higher Marine Fungi Archived 2013-04-22 at the Wayback Machine University of Mississippi. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- "Cool New Paper: Marine Fungi". Teaching Biology. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012.

- Gladfelter, Amy S.; James, Timothy Y.; Amend, Anthony S. (March 2019). "Marine fungi". Current Biology. 29 (6): R191–R195. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.009. PMID 30889385.

- E. B. Gareth Jones (2000). "Marine fungi: some factors influencing biodiversity" (PDF). Fungal Diversity. 4: 53–73.

- Paz, Z.; Komon-Zelazowska, M.; Druzhinina, I. S.; Aveskamp, M. M.; Shnaiderman, A.; Aluma, Y.; Carmeli, S.; Ilan, M.; Yarden, O. (30 January 2010). "Diversity and potential antifungal properties of fungi associated with a Mediterranean sponge". Fungal Diversity. 42 (1): 17–26. doi:10.1007/s13225-010-0020-x.

- Holmquist, G. U.; H. W. Walker & Stahr H. M. (1983). "Influence of Temperature, pH, Water Activity and Antifungal Agents on Growth of Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus". Journal of Food Science. 48 (3): 778–782. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1983.tb14897.x.

- Richards, Thomas A.; Jones, Meredith D.M.; Leonard, Guy; Bass, David (15 January 2012). "Marine Fungi: Their Ecology and Molecular Diversity". Annual Review of Marine Science. 4 (1): 495–522. Bibcode:2012ARMS....4..495R. doi:10.1146/annurev-marine-120710-100802. PMID 22457985.

- Marine Fungi Retrieved 2012-02-06.

- Silliman B. R. & S. Y. Newell (2003). "Fungal farming in a snail". PNAS. 100 (26): 15643–15648. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10015643S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2535227100. PMC 307621. PMID 14657360.

- Disease Analysis in San Juan Archipelago Archived 2013-09-12 at the Wayback Machine Friday Harbor Laboratories Seagrass Lab. Retrieved 2012-02-06.

- Short, Frederick T.; Robert G. Coles (2001-11-06). Global seagrass research methods. p. 414. ISBN 9780080525617.

- Moss, Stephen T. (1986). The biology of marine fungi. pp. 65–70. ISBN 9780521308991.

- Osterhage C.; R. Kaminsky; G. König & A. D. Wright (2000). "Ascosalipyrrolidinone A, an Antimicrobial Alkaloid, from the Obligate Marine Fungus Ascochyta salicorniae". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 65 (20): 6412–6417. doi:10.1021/jo000307g. PMID 11052082.

- Spribille, Toby; Tuovinen, Veera; Resl, Philipp; Vanderpool, Dan; Wolinski, Heimo; Aime, M. Catherine; Schneider, Kevin; Stabentheiner, Edith; Toome-Heller, Merje; Thor, Göran; Mayrhofer, Helmut; Johannesson, Hanna; McCutcheon, John P. (29 July 2016). "Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens". Science. 353 (6298): 488–492. Bibcode:2016Sci...353..488S. doi:10.1126/science.aaf8287. PMC 5793994. PMID 27445309.

- Freshwater and marine lichen-forming fungi Retrieved 2012-02-06.

- Yuan, X.; Xiao, S; Taylor, TN (13 May 2005). "Lichen-Like Symbiosis 600 Million Years Ago". Science. 308 (5724): 1017–1020. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1017Y. doi:10.1126/science.1111347. PMID 15890881. S2CID 27083645.

- Gaydos, Joseph K.; Balcomb, Kenneth C.; Osborne, Richard W.; Dierauf, Leslie. A Review of Potential Infectious Disease Threats to Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-09-28.

- Fungal infections of farmed salmon and trout Retrieved 2012-02-06.

- Gil-Turnes, M. Sofia & William Fenical (1992). "Embryos of Homarus americanus are Protected by Epibiotic Bacteria". The Biological Bulletin. 182 (1): 105–108. doi:10.2307/1542184. JSTOR 1542184. PMID 29304709.

- Rédou, Vanessa; Navarri, Marion; Meslet-Cladière, Laurence; Barbier, Georges; Burgaud, Gaëtan (2015-05-15). Brakhage, A. A. (ed.). "Species Richness and Adaptation of Marine Fungi from Deep-Subseafloor Sediments". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 81 (10): 3571–3583. doi:10.1128/AEM.04064-14. ISSN 0099-2240. PMC 4407237. PMID 25769836.

- Mouton, Marnel; Postma, Ferdinand; Wilsenach, Jac; Botha, Alfred (August 2012). "Diversity and Characterization of Culturable Fungi from Marine Sediment Collected from St. Helena Bay, South Africa". Microbial Ecology. 64 (2): 311–319. doi:10.1007/s00248-012-0035-9. ISSN 0095-3628. PMID 22430506.

- Shoun, H.; Tanimoto, T. (1991-06-15). "Denitrification by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum and involvement of cytochrome P-450 in the respiratory nitrite reduction". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266 (17): 11078–11082. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 2040619.

- Amend, Anthony; Burgaud, Gaetan; Cunliffe, Michael; Edgcomb, Virginia P.; Ettinger, Cassandra L.; Gutiérrez, M. H.; Heitman, Joseph; Hom, Erik F. Y.; Ianiri, Giuseppe; Jones, Adam C.; Kagami, Maiko (2019-03-05). Garsin, Danielle A. (ed.). "Fungi in the Marine Environment: Open Questions and Unsolved Problems". mBio. 10 (2): e01189–18, /mbio/10/2/mBio.01189–18.atom. doi:10.1128/mBio.01189-18. ISSN 2150-7511. PMC 6401481. PMID 30837337.

- Hassett, B. T.; Gradinger, R. (2016). "Chytrids dominate arctic marine fungal communities". Environmental Microbiology. 18 (6): 2001–2009. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13216. ISSN 1462-2920. PMID 26754171.

- Moghadamtousi, Soheil; Nikzad, Sonia; Kadir, Habsah; Abubakar, Sazaly; Zandi, Keivan (2015-07-22). "Potential Antiviral Agents from Marine Fungi: An Overview". Marine Drugs. 13 (7): 4520–4538. doi:10.3390/md13074520. ISSN 1660-3397. PMC 4515631. PMID 26204947.

- Deshmukh, Sunil K.; Prakash, Ved; Ranjan, Nihar (2018-01-05). "Marine Fungi: A Source of Potential Anticancer Compounds". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8: 2536. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.02536. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 5760561. PMID 29354097.

- Zhou, Songlin; Wang, Min; Feng, Qi; Lin, Yingying; Zhao, Huange (December 2016). "A study on biological activity of marine fungi from different habitats in coastal regions". SpringerPlus. 5 (1): 1966. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-3658-3. ISSN 2193-1801. PMC 5108748. PMID 27933244.

- Xu, Lijian; Meng, Wei; Cao, Cong; Wang, Jian; Shan, Wenjun; Wang, Qinggui (2015-06-02). "Antibacterial and Antifungal Compounds from Marine Fungi". Marine Drugs. 13 (6): 3479–3513. doi:10.3390/md13063479. ISSN 1660-3397. PMC 4483641. PMID 26042616.

- Hassett, B. T.; Gradinger, R. (June 2016). "Chytrids dominate arctic marine fungal communities". Environmental Microbiology. 18 (6): 2001–2009. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13216. PMID 26754171.