Manganese, Minnesota

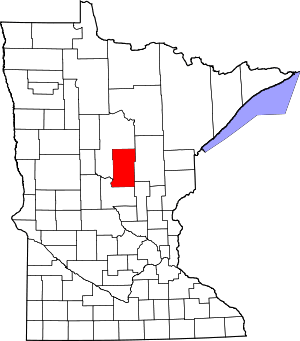

Manganese is a ghost town in the U.S. State of Minnesota that was inhabited between 1912 and 1960. It was built in Crow Wing County on the Cuyuna Iron Range in sections 23 and 28 of Wolford Township, about 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Trommald, Minnesota.[2][3] After its formal dissolution, Manganese was absorbed by Wolford Township; the former town site is located between Coles Lake and Flynn Lake. First appearing in the U.S. Census of 1920 with an already dwindling population of 183,[4] the village was abandoned by 1960.[5]

Manganese | |

|---|---|

Manganese  Manganese | |

| Coordinates: 46°31′39″N 94°00′35″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| County | Crow Wing |

| Elevation | 1,250 ft (380 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| Area code(s) | 218 |

| GNIS feature ID | 654881[1] |

The discovery of the Cuyuna Iron Range was an accident, made by the chance observation of a compass needle irregularity while Cuyler Adams was exploring the area with his St. Bernard, named "Una". It occurred to him that a vast body of iron ore, buried deep underground, might be responsible for the discrepancy. Nearly fifteen years after painstakingly mapping these compass deflections, test drilling by Adams in May of 1903 discovered manganiferous ore near Deerwood, Minnesota.[6] Another iron rush began for Minnesota, and new mining communities began to blossom along the width and breadth of the "Cuyuna" Iron Range, named by combining the first syllable of Adams' given name and that of his dog.[7]

Manganese was one of the last of these communities to be established, and named after the mineral located in abundance.[2][8] Unlike a mining "location", company towns built by the mining companies to house workers for their mines while they retained ownership of the land, Manganese was an incorporated community. At its peak around 1919, Manganese had two hotels, a bank, two grocery stores, a lumber yard, a livery stable, a barbershop, a pool room, a show hall and a two room school, and housed a population of nearly 600.[9][10] After the end of World War I, the population of Manganese went in to steady decline, resulting in complete abandonment by 1960.[11]

History

Establishment

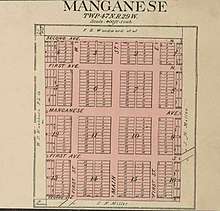

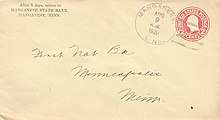

Manganese was platted by the Duluth Land and Timber Company in 1911, established on March 13, 1912, and incorporated on November 10, 1913, with 960 acres (390 ha) in the corporate limits.[2][9] An official U.S. Post Office opened in 1912 and remained in operation through 1924.[2][13] In 1914, the town site had a crew of men and teams building streets with concrete sidewalks and curbing, although the clay roads were never paved. The Soo Line Railroad constructed a siding and began excavation for a passenger and freight depot.[2][14][15] The Fitger Brewing Company built a $10,000, two-story hotel, complete with dining room and bar. By 1919, Manganese had two hotels, a bank, two grocery stores, a lumber yard, a livery stable, a barbershop, a pool room, a show hall, and a two room school, and housed a population of nearly 600. That same year, the village issued bond for a $30,000 waterworks project, and built a 100-foot water tower with a 30,000-gallon capacity.[16] The community was composed of many immigrants, including Finns, Croatians, Austrians, Swedes, and Irish.[10][16] Children attended school in Manganese through the eighth grade, attending high school in nearby Crosby, Minnesota. Known then as Independent School District No. 86, the school had indoor plumbing and later its own well, constructed by the Works Progress Administration.[10][17] Over time, the village of Manganese had three wells, all of which collapsed at some point due to the heavy clay soils.[10]

The Soo Line Railroad furnished rail transportation to the village and mines, while passenger connections with the other Cuyuna Iron Range towns was made through the operation of buses owned by the Cuyuna Range Transportation Company.[9] It is rumored that Henry Ford once visited Manganese when he was touring the Algoma mine on behalf of the Ford Motor Company. Ford was never observed, but his private rail car was parked on the Manganese siding.[9]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1920 | 183 | — | |

| 1930 | 96 | −47.5% | |

| 1940 | 62 | −35.4% | |

| 1950 | 41 | −33.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[11] | |||

Manganese was named after the mineral located in abundance nearby, and boasted of its high grade manganiferous ores. The mines surrounding the community included the Merrit No. 4, Algoma, Gloria, Preston, and Milford mines. During late World War I, all of these mines were running at full capacity, furnishing about 90% of the manganese used during the war.[9] Seven citizens from Manganese served in the military during World War I, including Harry Hosford, who later survived the Milford mine disaster.[18][19] Many of Manganese's residents worked in the Milford mine, which flooded on February 5, 1924, a result of blasting in a drift that extended beneath Foley Lake. Many residents of the community were superstitious and convinced that both the town and the mine were cursed.[20]

After the armistice was signed, the demand for manganiferous ore decreased.[9] With the advent of the Great Depression, mining operations ceased. The Soo Line tore up the track to Manganese in 1930. Little employment was left in the community, and residents relocated to find new jobs. About one house per day was moved out of town. Very few photos of Manganese are known to exist. Never a wealthy community, residents had no money for cameras, considered a luxury item during the Depression.[10]

In 1938, a Wesleyan Methodist Church and Sunday school was founded. There were generally four Sunday school classes, based on the ages of the children. Occasional revival meetings were held, and guest pastors came in for services. The congregation came from Trommald, Mission, Wolford, and Perry Lake, in addition to Manganese. After World War II, the church was sold and torn down after the congregation was no longer able to appoint a pastor.[21]

Abandonment

Most of the remaining residents moved out around 1955. Structures that weren't moved out of the community were torn down. After all of the residents left, the clay roads continued to be maintained and the street lights remained on for many years.[10][17] In 1959, the village of Ironton, one of the creditors for the village of Manganese, petitioned Crow Wing County in the state of Minnesota for the community's dissolution. Einer R. Andersen, then Crow Wing County Auditor, was appointed as its receiver, and creditors of the village of Manganese were given six months to file a claim. Notices sent to the last known village officers were refused. Bids were accepted for the sale of the Manganese water tower and the frame building housing the old village hall, with the condition that all debris be disposed of at the expense of the buyer. The steel water tower, with an estimated weight of 100 tons of scrap metal, was valued at $1,200; however, the sale and salvage of the water tower only yielded net proceeds of $200. Had the water tower remained, it would have undoubtedly been named to the National Register of Historic Places along with the other Cuyuna Iron Range municipally-owned elevated metal water tanks.[23] The final hearing regarding the dissolution of Manganese was held on July 17, 1961. Manganese was formally dissolved and absorbed by Wolford Township.[5][24]

After the town was abandoned, only remnants of sidewalks, rubble, building foundations and various abandoned items remained.[10][16][20] The site was slowly overgrown with trees, roots, shrubs, and grass, which began to uproot and crack the concrete sidewalks and overtake the remaining grid pattern of roads. Most of the remaining structures succumbed to the elements. Old building foundations and basements were buried in the brush.[3] Trees covered what was once a land occupied by numerous buildings, and the entire town site was consumed by the steady growth of natural vegetation. In the 1990s, the majority of the land which comprised the former town site was purchased, and a gate was posted along with a "no trespassing" sign at the southeast entrance to the city.[3] The privately owned land today is starting to undergo a sort of resettlement. Called Manganese Base Camp, the old wooded lots, about one-third of an acre each, are being cleared and redeveloped as primitive campsites, without electricity, running water, or waste disposal services. Since 2017, Base Camp has hosted an annual Manganese Days Festival. The event is open to the public as a way to honor the former village, learn of its history, and explore the old town site of Manganese.[25]

Geology

Manganese lay atop the iron-rich Trommald formation, the main ore-producing unit of the North Range district of the Cuyuna Iron Range.[26] The Trommald formation has been variously correlated with other iron formations of the Animikie Group,[27] deposited during the early Proterozoic age,[26][28] and is unique in the Lake Superior region because of the amount of manganese in part of the of iron formation and ore.[29][30] In general, the stratigraphic column of the Trommald formation ranges from 45 to 820 feet (14 to 250 m) thick and consists of at least two mappable iron formation facies, one thick-bedded and cherty, divided by an aegirine zone, the other thin-bedded and slaty with a tourmaline zone at the base.[31] The facies are sometimes separated by a third black laminated carbonate-silicate iron formation. Gray phyllite lie above and below,[31] capped with topsoil consisting of overlying morainic material and clay-rich till.[27]

It is not possible to determine the mineral content in the iron formation from top to bottom in any one location due to the great diversity of ore textures and the shape of the ore bodies.[32] Considerable variation exists in the character and composition of the ores, varying greatly from 20 to 60 percent iron and 0.5 to 15 percent manganese, with local areas of manganese as high as 50 percent.[26][27][33] Most manganese is finely disseminated as an integral part of the iron ore.[34] Ores of the Milford mine were brown and manganiferous; ores from the Gloria mine were black and slaty brown maganiferous; ores from the Algoma mine were ferruginous manganese.[35] The ores contained on average about 43% iron and 10% manganese.[28]

The Trommald formation and adjacent Emily district are the largest resource of manganese in the United States.[27][36][37] The largest high-grade deposit of manganiferous ore is located about 14 miles (23 km) north of Manganese on a five-acre site at the edge of Emily.[38][39][40] Valuable in steel and aluminum prodcution, manganese is also used to make batteries.[41] There is a local push to "scram" the stockpiles of ore found in the old waste rock of the Cuyuna Iron Range. This mining process is significantly less invasive than traditional blasting and crushing, but processing of some stockpiles would disrupt the Cuyuna Lakes Mountain Bike Trails,[42][43] which have been a boon to tourism since the last manganiferous ore was shipped from the Cuyuna Range in 1984.[44] This potential for ore processing has created debate as to whether mining and mountain biking can coexist.[45] The use of former underground Cuyuna Range mines as a means of compressed-air energy storage has also been investigated by researchers at the University of Minnesota.[46]

Geography and climate

Manganese lay at an elevation of 1,250 feet (380 m) in Crow Wing County, Minnesota, about 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Brainerd and 91 miles (146 km) west-southwest of Duluth.[1][27] The nearest cities to Manganese were Trommald, approximately 2 miles (3 km) to the south-southwest, and Wolford, approximately 2 miles (3 km) to the northeast.[38] Manganese was located to the west of Crow Wing County Road 30, about 5 miles (8 km) miles north of Minnesota State Highway 210 and 3 miles (5 km) miles west of Minnesota State Highway 6.[47]

Manganese was laid out with three primary north–south streets: First Street East, Main Street and First Street West. Second Avenue North, First Avenue North, Manganese Avenue, First Avenue South (now Old Manganese Road), and Second Avenue South traversed Manganese from east to west.[12] The Soo Line right of way bisected the community on the east side of Manganese from the southwest to the northeast.[48] First Avenue North extended to the Milford mine.[49]

Manganese was in the Laurentian Mixed Forest Province in the Brainerd Lakes Area of north central Minnesota. Precipitation ranges from about 21 inches (53 cm) annually along the western border of the forest to about 32 inches (81 cm) at its eastern edge. Average annual temperatures are about 34 °F (1 °C) along the northern part of the forest, rising to 40 °F (4 °C) at its southern extreme.[50]

July is the warmest month, when the average high temperature is 81 °F (27 °C) and the average low is 59 °F (15 °C). January is the coldest, with an average high temperature of 20 °F (−7 °C) and average low of 1 °F (−17 °C).[51] The spring rains wreaked havoc on Manganese clay streets, which was cited as one of the reasons for its abandonment.[10][16]

References

- "Manganese". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Upham 2001, p. 160.

- "Manganese, Minnesota". Wikimapia. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Census 1922, p. 238.

- Census 1964, p. 26.

- Clark, Neil M. (February 1922). "How the Needle of a Compass Pointed the Way to Fortune". The American Magazine. New York: The Crowell Publishing Company. 93: 86–93. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Upham 2001, p. 158.

- "A Guide to Minnesota Communities". LakesnWoods. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Anon. "Manganese, Minnesota". Archival Material. Crosby, MN: Cuyuna Iron Range Heritage Network.

- Sloan, Jim (May 8, 1985). "Manganese Revisited". Brainerd Dispatch (MN). pp. 1N, 3N.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- Standard Atlas, Crow Wing County, Minnesota (Map). [1:4,800]. Chicago: Geo. A. Ogle & Co. 1913. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- "Crow Wing County". Jim Forte Postal History. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- Leighton 1998, p. 19.

- "Manganese a Busy Town". Brainerd Dispatch (MN). July 3, 1914.

- Cuyuna Country Heritage Preservation Society 2002, p. 190.

- Cuyuna Country Heritage Preservation Society 2002, p. 191.

- Minnesota War Records Commission. "Manganese, Minnesota". World War I Military Service Records, 1918–1920. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

- Fitzgerald, John (November 3, 2016). "Milford Mine Disaster, 1924". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- Christensen, G. (May 25, 2005). "Guide to the Ghost Towns of Minnesota". Ghost Town USA. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Cuyuna Country Heritage Preservation Society 2002, p. 193.

- "Landview". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Nomination Form: Cuyuna Iron Range Municipally-Owned Elevated Metal Water Tanks Thematic Resources" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. 1979. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- Manganese, Minnesota. "Crow Wing County: Manganese". Records, 1913-1960. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

- "Manganese Base Camp". Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Melcher, Frank; Morey, G. B.; McSwiggen, Peter L.; Cleland, J. M.; Brink, S. E. (1996). "RI-46 Hydrothermal Systems in Manganese-Rich Iron-Formation of the Cuyuna North Range, Minnesota: Geochemical and Mineralogical Study of the Gloria Drill Core". University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy. Minnesota Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Morey, G.B.; Broberg, J.; Beltrame, R.J.; Holtzman, R.C. (1977). Manganese-bearing ores of the Cuyuna Iron Range, east-central Minnesota, Phase 1. University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy (Report). Minnesota Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Cuyuna Iron Range District". Porter GeoConsultancy. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Schmidt 1963, p. 57.

- Morey 1990, p. 8.

- McSwiggen, Peter L.; Morey, Glenn B.; Cleland, Jane M. (1994). "The Origin of Aegirine in Iron Formation of the Cuyuna Iron Range, East-Central Minnesota" (PDF). The Canadian Minerologist. 32: 591. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Schmidt 1963, pp. 20, 55, 68.

- Morey 1990, pp. 11, 22.

- Schmidt 1963, p. 48.

- Schmidt 1963, pp. 67, 68.

- Morey 1990, p. 1.

- Robertson, Tom (June 4, 2009). "Underground in Emily, a mother lode of manganese". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Distance From To: Calculate distance between two addresses, cities, states, zipcodes, or locations". Map Developers. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Johnson, Brooks; Lovrien, Jimmy (1 September 2018). "Minnesota manganese deposit sits untapped despite growing market". Duluth News Tribune. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Crow Wing Power announces partnership to develop Emily manganese deposit". Brainerd Dispatch (MN). June 7, 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Burton, Michael; Egan, Kevin (January 2015). "Bringing Mining Back to the Cuyuna Range?" (PDF). Laurentian Vision Project. Brainerd Lakes Area Economic Development Corporation. p. 18. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Cuyuna Mountain Bike Trail System". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Cuyuna Range mining talk hails old ghosts". Minnesota Brown. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Rosemore, Lisa (February 28, 2014). "CUYUNA: The Lost Range". Hibbing Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Richardson, Renee (July 12, 2014). "Mining, mountain biking come head to head on Cuyuna Range". Inforum. Forum Communications Company. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Fosnacht, D. R.; Wilson, E. J.; Marr, J. D.; Carranza-Torres, C.; Hauck, S. A.; Teasley, R. L. (2015). Compressed-Air Energy Storage (CAES) in Northern Minnesota Using Underground Mine Workings and Above Ground Features (PDF) (Report). University of Minnesota Duluth: Natural Resources Research Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Minnesota Official Highway Map (Map). [1:760,320]. Minnesota Department of Highways. 1960. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- "Crow Wing County GIS Public Map Service". Interactive Map. Crow Wing County, Minnesota. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Terrell, Michelle M.; Gronhovd, Amanda (March 2015). Milford Mine National Register Historic District, Crow Wing County, Minnesota: Cultural Landscape Report (Report). Crow Wing County, Minnesota. p. 51. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Laurentian Mixed Forest Province". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on May 20, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- "National Centers for Environmental Information". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. United States Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

Sources

- Cuyuna Country Heritage Preservation Society (2002). Cuyuna Country: A People's History. II (First ed.). Brainerd, MN: Bang Printing Company. ISBN 978-0967745008.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leighton, Hudson (1998). Gazetteer of Minnesota Railroad Towns, 1861–1997. Roseville, MN: Park Genealogical Books. ISBN 978-0915709618. Retrieved July 27, 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morey, G. B. (1990). Geology and Manganese Resources of the Cuyuna Iron Range, East-Central Minnesota (PDF). St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Geological Survey. ISSN 0544-3105. Retrieved March 30, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmidt, Robert Gordon (1963). Geology and Ore Deposits of the Cuyuna North Range Minnesota (PDF). Washington: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1288964765. Retrieved March 30, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- United States, Bureau of the Census (1922). Fourteenth Census of the United States: 1920 (PDF). III. Washington: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1396464294. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- United States, Bureau of the Census (1964). U.S. Census of Population, 1960 (PDF). I, Pt. 25. Washington: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1390260830. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- Upham, Warren (2001). Minnesota Place Names: A Geographical Encyclopedia (Third ed.). St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0873513968. Retrieved July 27, 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manganese, Minnesota. |