Ludgate

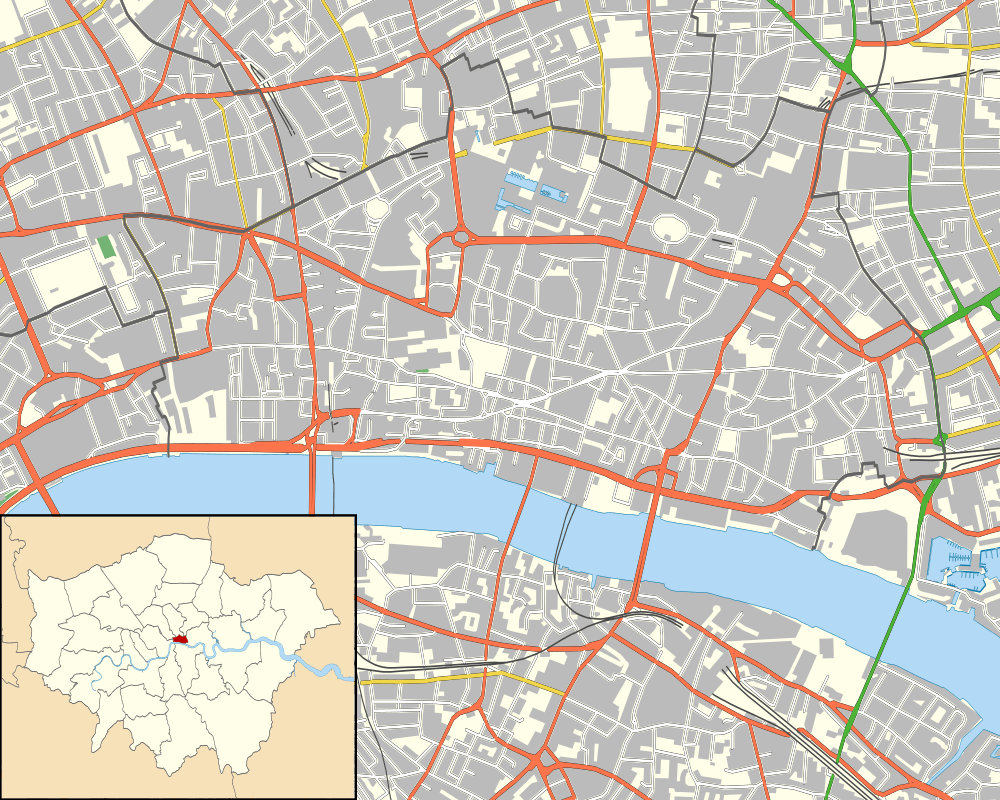

Ludgate was the westernmost gate in London Wall. The name survives in Ludgate Hill, an eastward continuation of Fleet Street, Ludgate Circus and Ludgate Square.

Etymology

Despite the claim by the Norman-Welsh Geoffry of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae that Ludgate was so-called having been built by the ancient British king called Lud—a manifestation of the god Nodens—the name is believed by later writers to be derived from "flood gate" or "Fleet gate",[1] from "ludgeat", meaning "back gate" or "postern",[2] or from the Old English term "hlid-geat"[3][4][5][6][7] a common Old English compound meaning "postern" or "swing gate".[3][4][5][5][7]

History

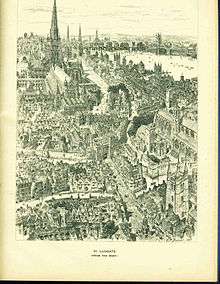

The Romans built a road along the north bank of the River Thames westwards through the gate later called Lud Gate as part of the fortifications of London. Guarding the road from the west, it led to the Romans' main burial mound in what is now Fleet Street. The gate stood just above a crossing of the Fleet River (this now runs underground). It stood almost opposite what is now St Martin's Church on what is now called Ludgate Hill. The site of the gate is marked by a plaque on the north side of Ludgate Hill, halfway between Ludgate Circus and St Paul's Cathedral.

Anti-royalist forces rebuilt the gate during the First Barons' War (1215–17) using materials recovered from the destroyed houses of Jews.[8] The rooms above the gate were used as a prison for petty offenders. The gate was one of three separate sites that bore the name Ludgate Prison. In 1378 it was decided that Newgate Prison would be used for serious criminals, and Ludgate for Freemen of the City and clergy who were imprisoned for minor offences such as debt. By 1419 it became clear that prisoners were far too comfortable here, as they were more likely to want to stay than to pay their debts and leave. They were all transferred to Newgate prison for this reason, although that prison was so overcrowded and unhealthy that they soon returned. It had a flat lead roof for prisoners to exercise on, as well as a 'large walking place' at ground level. The gate was rebuilt about 1450 by a man called Foster who at one time was lodged in the Debtor's Prison over the gate. He eventually became Sir Stephen Foster, Lord Mayor of London. His widow, Agnes, renovated and extended Ludgate and the Debtor's Prison and the practice of making the debtors pay for their own food and lodging was abolished. Her gift was commemorated by a brass wall plaque[9], which read:

Devout souls that pass this way,

For Stephen Foster, late mayor, heartily pray;

And Dame Agnes, his spouse, to God consecrate,

That of pity this house made, for Londoners in Ludgate;

So that for lodging and water prisoners here nought pay,

As their keepers shall answer at dreadful doomsday![10]

Rebuilt by the City in 1586, a statue of King Lud and his two sons was placed on the east side, and one of Queen Elizabeth I on the west.[8] These statues are now outside the church of St Dunstan-in-the-West, in Fleet Street. It was rebuilt again after being destroyed in the Great Fire. Like most of the other City gates it was demolished in 1760. The prisoners were moved to a section of the workhouse in Bishopsgate Street.

In literature

Ludd's Gate is mentioned in Bernard Cornwell's novel Sword Song, set during the reign of Alfred the Great.

Ludgate is mentioned in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, written around 1136. According to the pseudohistorical work[11][12] the name comes from the Welsh King Lud son of Heli whom he claims also gave his name to London.[13]

Ludgate appears in Walter de la Mare's poem "Up and Down", from Collected Poems 1901–1918, Vol. II: Songs of Childhood, Peacock Pie, 1920.

References

- Walter Thornbury (1878). "Ludgate Hill". Old and New London: Volume 1. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Bebbington, Gillian (1972). London Street Names. Batsford. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-7134-0140-0.

- Charters of Abingdon Abbey, Volume 2,Susan E. Kelly, Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-726221-X, 9780197262214, pp.623-266

- Geographical Etymology, Christina Blackie, pp.88

- English Place-Name society, Volume 36, The University Press, 1962, pp.205

- Middle English Dictionary, University of Michigan Press, 1998, ISBN 0-472-01124-3 pp. 972

- An encyclopaedia of London, William Kent, Dent, 1951, pp.402

- Timbs, John (1855). Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable Objects of Interest in the Metropolis. D. Bogue. p. 538.

- Caroline M. Barron, ‘Forster , Agnes (d. 1484)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 22 May 2017

- William Harvey (1863). London Scenes and London People: Anecdotes, Reminiscences, and Sketches of Places, Personages, Events, Customs, and Curiosities of London City, Past and Present. W.H. Collingridge. p. 256.

- Wright, Neil (1984). The Historia Regum Britannie of Geoffrey of Monmouth. Woodbridge, England: Boydell and Brewer. pp. xvii–xviii. ISBN 978-0-85991-641-7.

- "...the Historia does not bear scrutiny as an authentic history and no scholar today would regard it as such.": Wright (1984: xxviii)

- Ackroyd, Peter (2 December 2001). "'London'". New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

See also

- City gate

- City wall

- Fortifications of London

- London

- Lud son of Heli

- Nuada