List of kings of Babylon

The King of Babylon (Akkadian: šar Bābili), in some periods called the Governor or Viceroy of Babylon (Akkadian: šakkanakki Bābili), the King of Babylonia (Akkadian: šar māt Bābil) or the King of Karduniash (Akkadian: šar Karduniaš), was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon, and its kingdom (Babylonia) which existed as an independent kingdom from approximately the 19th century BC to the 6th century BC. Although Babylon tended to control most of southern Mesopotamia during its time as independent kingdom, it experienced two major periods of ascendancy, when Babylon dominated all of Mesopotamia and lands beyond; the Old Babylonian Empire (or "First dynasty", c. 1894–1595 BC) and the Neo-Babylonian Empire (or "Eleventh dynasty", 626–539 BC).

| King of Babylon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| First monarch | Sumu-abum |

| Last monarch | Nabonidus (native rule) Nidin-Bel (last native rebel) Gotarzes (last to be accorded title) |

| Formation | c. 1894 BC |

| Abolition | 539 BC (native rule) 336 BC (last native rebel) c. 80 BC (Parthian kings) |

| Appointer | Divine right, hereditary |

Of the eleven ancient dynasties that ruled Babylon from its foundation as an independent realm c. 1894 BC to the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BC, few were of native Babylonian ancestry. Several dynasties were of Kassite origin and there were also Assyrian, Elamite, Chaldean and Amorite rulers. Despite this, Babylon would often fiercely attempt to assert its independence and it repeatedly clashed against the other major Akkadian-speaking Mesopotamian kingdom of its time, Assyria. The period when the Assyrians ruled as kings of Babylon (the Neo-Assyrian Empire or "Tenth dynasty", 729–626 BC) saw repeated rebellions in Babylon, eventually culminating in a successful return to independence.

After the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, the title of King of Babylon continued to be used by monarchs of the successive empires which ruled Mesopotamia and the citizens of Babylon itself continued to apply it to whoever happened to rule their homeland at the time. Revolts aimed at independence continued unsuccessfully for centuries, with Babylon revolting as late as 336 BC, more than two centuries after it had native monarchs. The last recorded rulers to be accorded the title by the Babylonians were Parthian kings in the 1st century BC, after which the Akkadian language and Babylonian culture diminished and eventually disappeared.

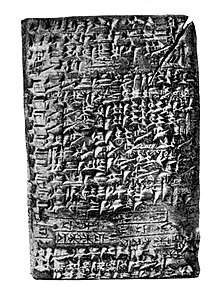

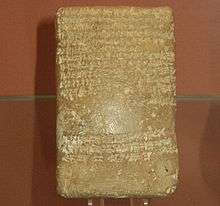

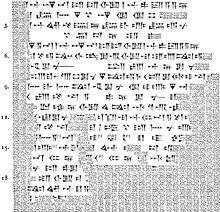

Babylonian King List

The Babylonian King List is a very specific ancient list of supposed Babylonian kings recorded in several ancient locations, and related to its predecessor, the Sumerian King List. As in the latter, contemporaneous dynasties are misleadingly listed as successive without comment.

There are three versions, which are known as "King List A"[1] (containing all the kings from the First Dynasty of Babylon to the Neo-Assyrian king Kandalanu), "King List B"[2] (containing only the two first dynasties), and "King List C"[3] (containing the first seven kings of the Second Dynasty of Isin). A fourth version was written in Greek by Berossus. The "Babylonian King List of the Hellenistic Age" is a continuation that mentions all the Seleucid kings from Alexander the Great to Demetrius II Nicator.[4]

List of kings

First dynasty (1894–1595 BC)

Also called the Amorite dynasty. The dates used follow the "middle chronology" (reign of Hammurabi 1792–1750 BC), the chronology most commonly encountered in literature, including many current textbooks on the archaeology and history of the ancient Near East.[5][6][7]

| No. | Image | King | Reign[8] | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sumu-abum Šumu-abum |

c. 1894–1881 BC

(13 years) |

Liberated Babylon from the control of Kazallu | The first king of Babylon, Sumu-abum freed a small region centered on Babylon, previously under the control of the city state Kazallu. He did not title himself as King of Babylon (and neither did his first three successors), suggesting that the city wasn't very important at the time. | [8][9] | |

| 2 | Sumu-la-El Šumu-la-El |

c. 1881–1845 BC

(36 years) |

Unknown | Sumu-la-El's year names reference the construction of a great city wall in Babylon. | [8][10] | |

| 3 | Sabium Sabūm |

c. 1845–1831 BC

(14 years) |

Unknown | Sabium's year names reference wars with Larsa and building projects in various cities in the region surrounding Babylon. | [8][11] | |

| 4 | Apil-Sin Apil-Sîn |

c. 1831–1813 BC

(18 years) |

Unknown | Apil-Sin's year names reference several building projects in Babylon, including temples and a new city wall. | [8][12] | |

| 5 | Sin-Muballit Sîn-Muballit |

c. 1813–1792 BC

(21 years) |

Son of Apil-Sin | The first ruler to actually title himself King of Babylon, began expanding the territory of his previously minor empire. | [8][13] | |

| 6 |  |

Hammurabi Ḫammu-rāpi |

c. 1792–1750 BC

(42 years) |

Son of Sin-Muballit | Hammurabi massively expanded Babylon's territory, founding the Old Babylonian Empire and bringing most of Mesopotamia under his control. He is also famous for the Code of Hammurabi, one of the oldest deciphered writings of significant length in the world. | [8][14] |

| 7 |  |

Samsu-iluna Šamšu-iluna |

c. 1750–1712 BC

(38 years) |

Son of Hammurabi | Samsu-iluna campaigned victoriously against several of Babylon's rebellious vassals in the wake of Hammurabi's death and though he was unable to keep the entirety of his father's empire together, he successfully retained control of the empire's heartlands in southern Mesopotamia. | [8] |

| 8 | Abi-Eshuh Abī-Ešuḫ |

c. 1712–1684 BC

(28 years) |

Son of Samsu-iluna | Babylonia experienced severe Elamite raids during Abu-Eshuh's reign. | [8] | |

| 9 | Ammi-Ditana Ammi-ditāna |

c. 1684–1647 BC

(47 years) |

Son of Abi-Eshuh | Largely peaceful reign; Ammi-Ditana was primarily engaged in building projects such as enriching and enlarging the temples. | [8] | |

| 10 | Ammi-Saduqa Ammi-Saduqa |

c. 1647–1626 BC

(21 years) |

Unknown | Largely peaceful reign; Ammi-Saduqa was primarily engaged in building projects such as enriching and enlarging the temples. | [8] | |

| 11 | Samsu-Ditana Šamšu-ditāna |

c. 1626–1595 BC

(31 years) |

Great-great-grandson of Hammurabi | The Old Babylonian Empire came to a sudden end during Samsu-Ditana's reign as the Hittites, for reasons unknown, sacked and destroyed the city. | [8] |

Babylon was sacked and destroyed by the Hittites in c. 1595 BC. The city and its kingdom was not firmly re-established until c. 1530 BC, by the Kassite king Agum II.[15]

Second dynasty (1732–1460 BC)

Also called the Sealand dynasty. These rulers might only have ruled Babylonia itself for the briefest of periods, being based in formerly Sumerian regions south of it. Nevertheless, it is often traditionally numbered the Second Dynasty of Babylon, and so it is listed here. Little is known of these rulers. They were counted as kings of Babylon in later king lists, succeeding the Amorite dynasty despite overlapping reigns.[16]

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Ilum-ma-ili Ilum-ma-ilī |

c. 1732 BC

(60 years) |

Unknown | |||

| 13 | Itti-ili-nibi Itti-ili-nībī |

(56 years) | Unknown | |||

| 14 | Damqi-ilishu Damqi-ilišu |

(36 years) | Unknown | |||

| 15 | Ishkibal Iškibal |

(15 years) | Unknown | [16] | ||

| 16 | Shushushi Šušši |

(24 years) | Brother of Ishkibal | [16] | ||

| 17 | Gulkishar Gulkišar |

(55 years) | Unknown | [16] | ||

| 18 | mDIŠ+U-EN mDIŠ-U-EN |

Unknown | Unknown | [16] | ||

| 19 | Peshgaldaramesh Pešgaldarameš |

(50 years) | Son of Gulkishar | [16] | ||

| 20 | Ayadaragalama Ayadaragalama |

(28 years) | Son of Peshgaldaramesh | [16] | ||

| 21 | Akurduana Akurduana |

(26 years) | Unknown | [16] | ||

| 22 | Melamkurkurra Melamkurkurra |

(7 years) | Unknown | [16] | ||

| 23 | Ea-gamil Ea-gamil |

c. 1460 BC

(9 years) |

Unknown |

Early Kassite rulers (1730–1530 BC)

These kings also did not actually rule Babylon, but their numbering scheme was continued for later Kassite Kings of Babylon, and so they are listed here. Little is known of these rulers. They were counted as kings of Babylon in later king lists, succeeding the Sealand dynasty despite overlapping reigns.[16]

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | Gandash Gandaš |

c. 1730 BC

(26 years) |

Unknown | |||

| 25 | Agum I Mahru Agum Maḫrû |

(22 years) | Unknown | |||

| 26 | Kashtiliash I Kaštiliašu |

(22 years) | Son of Agum I | [16] | ||

| 27 | Abi-Rattash Abi-Rattaš or Uššiašu |

Unknown | Son of Kashtiliash I | [16] | ||

| 28 | Kashtiliash II Kaštiliašu |

Unknown | Unknown | [16] | ||

| 29 | Ur-zigurumash Ur-zigurumaš or Tazzigurumaš |

Unknown | Descendant of Abi-Rattash | [16] | ||

| 30 | Hurbazum Ḫurbazum or Ḫarba-Šipak |

Unknown | Unknown | [16] | ||

| 31 | Shipta'ulzi Šipta’ulzi or Tiptakzi |

Unknown | Unknown | [16] |

Third dynasty (1530–1155 BC)

Also called the Kassite dynasty.

| No. | Image | King | Reign[17] | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32 | Agum II Kakrime Agum-Kakrime |

c. 1530 BC | Re-established Babylon | Established the long-lived Kassite dynasty as the rulers of Babylon. Portrays himself as the legitimate ruler and caring “shepherd” of both the Kassites and the Akkadians. | ||

| 33 | Burnaburiash I Burna-Buriaš |

c. 1515 BC | Son of Agum II | It is possible that Burnaburiash I, and not Agum II, was the actual first Kassite ruler to hold Babylon. Engaged in diplomacy with the Assyrian king Puzur-Ashur III. | ||

| 34 | Kashtiliash III Kaštiliašu |

c. 1500 BC | Son of Burnaburiash I | Only known from the Assyrian Synchronistic King List. | ||

| 35 | Ulamburiash Ulam-Buriaš |

c. 1480 BC | Son of Burnaburiash I | Conquered the Sealand Dynasty, establishing the Kassites as rulers of all of southern Mesopotamia. | ||

| 36 | Agum III Agum |

c. 1470 BC | Son of Kashtiliash III | The only Babylonian reference to Agum III is from an expedition he led against "the Sealand". | ||

| 37 |  |

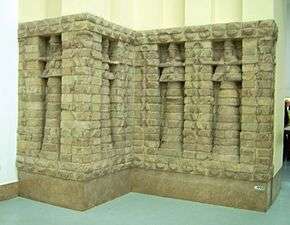

Karaindash Karaindaš |

c. 1410 BC | Unknown | One of the Kassite dynasty's more prominent rulers, Karaindash, Karaindash refurbished a temple at Uruk and engaged in diplomacy with Assyria and Egypt. | |

| 38 | Kadashman-harbe I Kadašman-Ḫarbe |

c. 1400 BC | Unknown | Campaigned against the against the Sutû and possibly against Elam. | ||

| 39 |  |

Kurigalzu I Kuri-Galzu |

c. 1375 BC | Son of Kadashman-harbe I | Kurigalzu I was responsible for one of the most extensive and widespread building programs for which evidence has survived in Babylonia. | |

| 40 |  |

Kadashman-Enlil I Kadašman-Enlil |

c. 1374–1360 BC

(14 years) |

Son of Kurigalzu I | Contemporary of Amenhotep III in Egypt, who he corresponded with. | [17] |

| 41 |  |

Burnaburiash II Burna-Buriaš |

c. 1359–1333 BC

(26 years) |

Son of Kadashman-Enlil I | Contemporary of Akhenaten in Egypt, who he famously corresponded with in the Amarna letters. | [17] |

| 42 | Kara-hardash Kara-ḫardaš |

c. 1333 BC | Son of Burnaburiash | Next to nothing is known of Kara-hardash's brief reign. | [17] | |

| 43 | Nazi-Bugash Nazi-Bugaš or Šuzigaš |

c. 1333 BC | Overthrew Kara-hardash, unrelated to previous kings | Next to nothing is known of Nazi-Bugash's brief reign. | [17] | |

| 44 | Kurigalzu II the Younger Kuri-Galzu |

c. 1332–1308 BC

(24 years) |

Son of Burnaburiash II, appointed king by the Assyrian king Ashur-uballit I | Because he shares his name with a predecessor who reigned just forty years prior, it is difficult to distinguish documents from their reigns since the Babylonians themselves did not use regnal numbers. | [17] | |

| 45 |  |

Nazi-Maruttash Nazi-Maruttaš |

c. 1307–1282 BC

(25 years) |

Son of Kurigalzu II | Warred against the Assyrians and the Elamites. | [17] |

| 46 |  |

Kadashman-Turgu Kadašman-Turgu |

c. 1281–1264 BC

(17 years) |

Son of Nazi-Maruttash | Contemporary of the Hittite king Ḫattušili III, with whom he concluded a formal treaty of friendship and mutual assistance, and also Ramesses II with whom he consequently severed diplomatic relations. | [17] |

| 47 |  |

Kadashman-Enlil II Kadašman-Enlil |

c. 1263–1255 BC

(8 years) |

Son of Kadashman-Turgu | Succeeded his father as a child and political power was exercised at first by an influential vizier, Itti-Marduk-balatu. In contrast to Kadashman-Turgu, Itti-Marduk-balatu was sharply anti-Hittite and severed relations with them, instead opting to engage diplomatically with Assyria. | [17] |

| 48 | Kudur-Enlil Kudur-Enlil |

c. 1254–1246 BC

(8 years) |

Unknown, claimed by the king list to be the son of Kadashman-Enlil II | The first Kassite king to have a wholly Babylonian name. Recorded as the son of Kadashman-Enlil II in king lists, which would be impossible with the dates provided. | [17] | |

| 49 | Shagarakti-Shuriash Šagarakti-Šuriaš |

c. 1245–1233 BC

(12 years) |

Unknown, claimed by the king list to be the son of Kudur-Enlil | Recorded as the son of Kurud-Enlil in king lists, probably impossible with the dates provided. Babylon probably faced economic problems during Shagarakti-Shuriash's reign. | [17] | |

| 50 |  |

Kashtiliash IV Kaštiliašu |

c. 1232–1225 BC

(8 years) |

Unknown, possibly son of Shagarakti-Shuriash | Warred against Assyria, which resulted in a catastrophic Assyrian invasion by Tukulti-Ninurta I and his own deposition and death. | [17] |

| 51 | Enlil-nadin-shumi Enlil-nādin-šumi |

c. 1224 BC

(6 months) |

Unknown, possibly installed as vassal king by the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I | Little contemporary evidence survives from Enlil-nadin-shumi's brief reign. Possibly deposed by invading Elamites. | [17] | |

| 52 | Kadashman-harbe II Kadašman-Ḫarbe |

c. 1223 BC

(1 year, 6 months) |

Unknown, possibly installed as vassal king by the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I | Little contemporary evidence survives from Kadashman-harbe II's brief reign. | [17] | |

| 53 |  |

Adad-shuma-iddina Adad-šuma-iddina |

c. 1222–1217 BC

(6 years) |

Unknown, possibly installed as vassal king by the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I | Usually identified as a vassal king to Assyria, though there is no contemporary evidence to support this. | [17] |

| 54 |  |

Adad-shuma-usur Adad-šuma-uṣur |

c. 1216–1187 BC

(30 years) |

Descendant of Kashtiliash IV | Had a wholly Babylonian name. Known for a rude letter sent to the Assyrian king Ashur-nirari III. | [17] |

| 55 |  |

Meli-Shipak Meli-Šipak or Melišiḫu |

c. 1186–1172 BC

(14 years) |

Son of Adad-shuma-usur | Commonly numbered "Meli-Shipak II", an error based on over-reliance of a single inscription which mentions a son of Kurigalzu II called Meli-Shipak. His reign marks the critical synchronization point in the chronology of the Ancient Near East. | [17][18] |

| 56 |  |

Marduk-apla-iddina I Marduk-apla-iddina |

c. 1171–1159 BC

(14 years) |

Son of Meli-Shipak | Most documents date to Marduk-apla-iddina I's reign are economic documents or texts relating to gifts distributed during the New Year's festival. Possibly overthrown by the Elamites. | [17] |

| 57 |  |

Zababa-shuma-iddin Zababa-šuma-iddina |

c. 1158 BC

(1 year) |

Unknown, probably unrelated to previous kings | Without obvious ties to the royal family, his means of becoming king are unknown. His reign saw invasions by the Assyrians and the Elamites. Overthrown by the Elamites. | [17] |

| 58 |  |

Enlil-nadin-ahi Enlil-nādin-aḫe or Enlil-šuma-uṣur |

c. 1157–1155 BC

(3 years) |

Unknown | The final king of the long-lived Kassite dynasty, probably deposed by the Elamites like his two predecessors. | [17] |

Fourth dynasty (1157–1025 BC)

The contemporary name of this dynasty, BALA PA.ŠE, is a paronomasia on the term išinnu, “stalk”, written as PA.ŠE and is the only apparent reference to the actual city of Isin.[19] It is therefore also called the Second Dynasty of Isin (after the Dynasty of Isin, which ruled Mesopotamia c. 1953–1717 BC) or Isin II.

| No. | Image | King | Reign[20] | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 59 | Marduk-kabit-ahheshu Marduk-kabit-aḫḫēšu |

c. 1157–1140 BC

(17 years) |

Unknown | Appears to have driven out the Elamite hordes from Babylonia in a series of campaigns. Also successfully campaigned against Assyria in the north. Might not have actually ruled from Babylon. | [20] | |

| 60 |  |

Itti-Marduk-balatu Itti-Marduk-balāṭu |

c. 1139–1132 BC

(8 years) |

Son of Marduk-kabit-ahheshu | Ruled from Babylon. Known chiefly from building inscriptions and economic documents. | [20] |

| 61 | Ninurta-nadin-shumi Ninurta-nādin-šumi |

c. 1131–1126 BC

(7 years) |

Unknown | Known for a condescending letter he sent to the Assyrian king Ashur-resh-ishi I, in which he scolds the king for missing a meeting in the border town Zaqqa. | [20] | |

| 62 |  |

Nebuchadnezzar I Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

c. 1125–1104 BC

(20 years) |

Son of Ninurta-nadin-shumi | Celebrated for centuries after his death, Nebuchadnezzar I is most famous for his victorious campaign against Elam, which saw him return the sacred statue of Marduk to Babylon after it had been stolen by the Elamites c. 1150 BC. | [20] |

| 63 |  |

Enlil-nadin-apli Enlil-nādin-apli |

c. 1103–1100 BC

(3 years) |

Son of Nebuchadnezzar I | Enlil-nadin-apli is known to have campaigned against Assyria during his brief reign. He was deposed by his uncle, Marduk-nadin-ahhe. | [20] |

| 64 |  |

Marduk-nadin-ahhe Marduk-nādin-aḫḫē |

c. 1099–1082 BC

(18 years) |

Usurper, son of Ninurta-nadin-shumi | Best known for his restoration of the Eganunmaḫ in Ur and the famines and droughts that accompanied his reign, Marduk-nadin-ahhe frequently warred against his rival, Tiglath-Pileser I of Assyria. | [20] |

| 65 |  |

Marduk-shapik-zeri Marduk-šāpik-zēri |

c. 1081–1069 BC

(13 years) |

Unknown, possibly son or brother of Marduk-nadin-ahhe | Contemporary of the Assyrian kings Tiglath-Pileser I and Ashur-bel-kala. Allied with the Assyrians to defeat the Arameans, whose constant raids posed a threat to both kingdoms. | [20] |

| 66 | Adad-apla-iddina Adad-apla-iddina |

c. 1068–1046 BC

(23 years) |

Unrelated to previous kings, appointed by Assyrian king Ashur-bel-kala | A vassal of the Assyrians, Adad-apla-iddina's reign was a golden age of scholarship, as attested in numerous inscriptions from the decades and centuries after his reign. | [20] | |

| 67 | Marduk-ahhe-eriba Marduk-aḫḫē-erība |

c. 1046 BC

(6 months) |

Unknown | The only contemporary document from Marduk-ahhe-eriba's brief reign is a land grant in a region north of Babylon. | ||

| 68 | Marduk-zer-X Marduk-zer-X |

c. 1045–1034 BC

(13 years) |

Unknown | Only appears in king lists, no contemporary documents are known. | [20] | |

| 69 |  |

Nabu-shum-libur Nabû-šumu-libūr |

c. 1033–1025 BC

(8 years) |

Unknown | Little contemporary evidence survives from Nabu-shum-libur's reign, but it was a time of political turmoil, possibly due to the Aramean raiders present throughout Mesopotamia. | [20] |

Fifth dynasty (1025–1005 BC)

Also called the Second Sealand dynasty, the evidence that this was a Kassite Dynasty is rather tenuous.[21]

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70 | Simbar-shipak Simbar-Šipak |

c. 1025–1008 BC

(17 years) |

Overthrew Nabu-shum-libur | Reigning during the turbulent times that had caused the fall of the Isin dynasty preceding him, Simbar-shipak was originally a soldier from southern Mesopotamia and seems to have stabilized the situation somewhat. | [16] | |

| 71 | Ea-mukin-zeri Ea-mukin-zēri |

c. 1008 BC

(3 months) |

Overthrew Simbar-shipak | Killing Simbar-shipak, Ea-mukin-zeri ruled for only three months before being deposed and killed. | [16] | |

| 72 | Kashshu-nadin-ahi Kaššu-nādin-aḫi |

c. 1007–1005 BC

(3 years) |

Overthrew Ea-mukin-zeri | Kashshu-nadin-shumi's reign saw extreme famine but not much else is known. | [16] |

Sixth dynasty (1004–985 BC)

Also called the Bīt-Bazi dynasty after the region from which this minor Kassite clan originated.[22] This dynasty ruled from the city Kar-Marduk, an otherwise unknown location which might have been better protected against raids from nomadic groups than Babylon itself.[23]

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 73 | Eulmash-shakin-shumi Eulmaš-šākin-šumi |

c. 1004–988 BC

(17 years) |

Overthrew Kashshu-nadin-ahi | Appears to have seized the throne and moved the capital to Kar-Marduk. | [16] | |

| 74 | Ninurta-kudurri-usur I Ninurta-kudurrῑ-uṣur |

c. 987–985 BC

(2 years) |

Unknown | Might be the king referred to in the Babylonian text Prophecy A, in which his reign is experiences ominous events indicating that the end of the world is near. | [16][24] | |

| 75 | Shirikti-shuqamuna Širikti-šuqamuna |

c. 985 BC

(3 months) |

Brother of Ninurta-kudurri-usur I | Contemporary of the Assyrian king Ashur-rabi II. | [16] |

Seventh dynasty (984–980 BC)

Also called the Elamite dynasty.

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 76 | Mar-biti-apla-usur Mār-bīti-apla-uṣur |

c. 984–980 BC

(4 years) |

Unknown | The only king of the short-lived seventh dynasty, Mar-biti-apla-usur. The circumstances of how the previous dynasty ended and Mar-biti-apla-usur gained the throne are unknown, but he was not regarded as a usurper by later Babylonian authors. | [16] |

Eighth dynasty (979–943 BC)

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 77 |  |

Nabu-mukin-apli Nabû-mukin-apli |

c. 979–943 BC

(36 years) |

Unknown | A contemporary of the Assyria king Tiglath-Pileser II, few sources survive from Nabu-mukin-apli's reign. He was the ancestor of the early kings of the Ninth dynasty and Babylon experienced a series of devastating Aramean raids during his tenure as king. | [16] |

Ninth dynasty (943–729 BC)

Also called the Dynasty of E.

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 78 | Ninurta-kudurri-usur II Ninurta-kudurrῑ-uṣur |

c. 943 BC

(8 months and 12 days) |

Son of Nabu-mukin-apli | No contemporary documents survive from the reign of Ninurta-kudurri-usur II. | [16] | |

| 79 | Mar-biti-ahhe-iddina Mār-bῑti-aḫḫē-idinna |

c. 943–920 BC

(23 years) |

Son of Nabu-mukin-apli | Known only from king lists, a brief mention in a chronicle and as a witness on a kudurru from the reign of his father. | [16] | |

| 80 | Shamash-mudammiq Šamaš-mudammiq |

c. 920–900 BC

(20 years) |

Unknown | Contemporary of the Assyrian king Adad-nirari II. | [16] | |

| 81 | Nabu-shuma-ukin I Nabû-šuma-ukin |

c. 900–888 BC

(22 years) |

Unknown | Warred with the Assyrian king Adad-nirari II but enjoyed good diplomatic relations with his successor, Tukulti-Ninurta II. | [16] | |

| 82 |  |

Nabu-apla-iddina Nabû-apla-iddina |

c. 888–855 BC

(33 years) |

Son of Nabu-shuma-ukin I | Avoided conflict with the resurging Assyrian Empire under its king Ashurnasirpal II and engaged in diplomacy with his successor, Shalmaneser III. He worked on reconstructing temples and his reign saw a literary revival with the copying of many older works. | [16] |

| 83 |  |

Marduk-zakir-shumi I Marduk-zâkir-šumi |

c. 855–819 BC

(36 years) |

Son of Nabu-apla-iddina | Defeated the revolt of his brother Marduk-bēl-ušati with the aid of his ally, Shalmaneser III of Assyria. Marduk-zakir-shumi I returned the favour by helping defeat the revolt of Assur-danin-pal, who aspired to depose Shalmaneser III. | [16] |

| 84 |  |

Marduk-balassu-iqbi Marduk-balāssu-iqbi |

c. 819–813 BC

(6 years) |

Son of Marduk-zakir-shumi I | Warred with Shamshi-Adad V of Assyria, who was married to Marduk-balassu-iqbi's sister Shammuramat. Deposed by the Assyrians after reigning 6 years. | |

| 85 | Baba-aha-iddina Bāba-aḫa-iddina |

c. 813–811 BC

(2 years) |

Unknown | Was deposed by Shamshi-Adad V of Assyria, after which Babylonia was left kingless for a few years. | ||

| 811–800 BC: after an interregnum lasting several years, a sequence of five kings, whose names are not recorded, rule Babylon before the beginning of Ninurta-apla-X's reign | ||||||

| 91 | Ninurta-apla-X Ninurta-apla-X |

c. 800–790 BC

(10 years) |

Unknown | No documents survive from the reign of Ninurta-apla-X. | ||

| 92 | Marduk-bel-zeri Marduk-bēl-zēri |

c. 790–780 BC

(10 years) |

Unknown | Known from a single economic text from the southern city of Udāni. | [25] | |

| 93 | Marduk-apla-usur Marduk-apla-uṣur |

c. 780–769 BC

(11 years) |

Unknown | A Chaldean tribal leader who successfully ascended to the Babylonian throne. Unrelated to previous and later kings. | [26] | |

| 94 | Eriba-Marduk Erība-Marduk |

c. 769–761 BC

(8 years) |

Unknown | Also a Chaldean, Eriba-Marduk was latergiven the title “re-establisher of the foundations of the land" and was credited with restoring stability to the country after years of turmoil. | [27] | |

| 95 |  |

Nabu-shuma-ishkun Nabû-šuma-iškun |

c. 761–748 BC

(12 years) |

Unknown | Apparently a weak ruler whose reign saw many regional officials gain increasing autonomy. | [28] |

| 96 | Nabonassar Nabû-nāṣir |

748–734 BC

(14 years) |

Overthrew Nabu-shuma-ishkun | Brought native Babylonian rule back after a series of Chaldean monarchs. Both the Babylonian Chronicle and the Ptolemaic Canon begin with his accession to the throne. | ||

| 97 | Nabu-nadin-zeri Nabû-nādin-zēri |

734–732 BC

(2 years) |

Son of Nabonassar | Deposed and killed by Nabu-shuma-ukin II (who had originally been one of his regional officials) after just two years as king. | ||

| 98 | Nabu-shuma-ukin II Nabû-šuma-ukin |

732 BC

(1 month and 2 days) |

Overthrew Nabu-nadin- | Deposed and killed by the Chaldean chief Nabu-mukin-zeri after just little over a month as king. | ||

| 99 |  |

Nabu-mukin-zeri Nabû-mukin-zēri |

732–729 BC

(3 years) |

Overthrew Nabu-shuma-ukin II | The political instability of Babylonia was taken advantage of by the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III who invaded the region in 731 BC. After two years of conflict, Nabu-mukin-zeri was deposed and Tiglath-Pileser took the throne of Babylon. | |

Tenth dynasty (729–626 BC)

The Tenth dynasty refers to the period of Assyrian rule over Babylon. The kings Sargon, Sennacherib, Ashur-nadin-shumi, Esarhaddon, Ashurbanipal, Shamash-shum-ukin and Sinsharishkun were part of the contemporary Assyrian royal family (many of them also being the kings of Assyria), the Sargonid dynasty.

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 |  |

Tiglath-Pileser Tukultī-apil-Ešarra |

729–722 BC

(7 years) |

King of Assyria, conquered Babylon | Neo-Assyrian King who conquered Babylon and was proclaimed as Babylonian king. Enumerated as Tiglath-Pileser III as King of Assyria. | [29][30] |

| 101 |  |

Shalmaneser Šulmanu-ašaridu |

727–722 BC

(5 years) |

Son of Tiglath-Pileser III | Continued the policies of Tiglath-Pileser III but was not as effective militarily, appears to have been a poor administrator who overtaxed the citizens of the empire. Probably assassinated in a coup d'état by his younger brother Sargon II, who took the throne. Enumerated as Shalmaneser V as King of Assyria. | [31] |

| 102 |  |

Marduk-apla-iddina II Marduk-apla-iddina |

722–710 BC (12 years) |

Babylonian rebel | Rebelling against the Assyrians, Marduk-apla-iddina successfully maintained Babylonian independence for more than a decade before being defeated by the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II in 710 BC. He briefly regained power in 703 BC. | |

| 103 | .jpg) |

Sargon Šarru-kīn |

710–705 BC (5 years) |

Son of Tiglath-Pileser III, reconquered Babylon | Sargon was a brilliant administrator and military leader who expanded the empire to its greatest extent yet. Sargon's successful campaigns saw the treasury of Assyria grow and he eventually founded a new capital, Dur-Sharrukin ("fortress of Sargon"). He was killed in battle by the Tabal people in Anatolia. Enumerated as Sargon II as King of Assyria. | [31] |

| 104 |  |

Sennacherib Sîn-ahhe-erība |

705–703 BC (2 years) |

Son of Sargon | Sennacherib is most famous for conquering Israel, Judah and many Greek-speaking parts of Anatolia. Sennacherib moved the Assyrian capital to Nineveh, which he expanded with great gardens and architecture. Sennacherib plundered and desecrated Babylon, seen as great sacrilege, and was assassinated in a conspiracy by two of his sons. | [31] |

| 105 | Marduk-zakir-shumi II Marduk-zâkir-šumi |

703 BC (a few months) |

Babylonian rebel | Rebelling against Sennacherib, Marduk-zakir-shumi II's reign was brief and he was soon replaced by Marduk-apla-iddina II, who returned to the throne. | ||

| Marduk-apla-iddina II briefly regained power in 703 BC, ruling for nine months before fleeing and later dying in exile. | ||||||

| 106 | Bel-ibni Bel-ibni |

703–700 BC (3 years) |

Appointed as vassal king by Sennacherib | Appointed by Sennacherib after the Babylonian revolt was defeated in the belief that direct control of Babylon was infeasible, Bel-ibni soon conspired with Assyria's enemies to overthrow Sennacherib, after which he was deposed. | ||

| 107 |  |

Ashur-nadin-shumi Aššur-nādin-šumi |

700–694 BC (6 years) |

Son of Sennacherib, appointed vassal king | Bel-ibni was replaced as king by Ashur-nadin-shumi, Sennacherib's son and heir. A few years thereafter, the Elamites attacked Babylon, capturing and executing Ashur-nadin-shumi. | [16] |

| 108 | Nergal-ushezib Nergal-ushezib |

694–693 BC (1 year) |

Babylonian rebel | Appointed by the Elamites, Nergal-ushezib was soon defeated in battle near Nippur by Sennacherib, who wished to avenge the death of his son. | [16] | |

| 109 | Mushezib-Marduk Mushezib-Marduk |

693–689 BC (4 years) |

Babylonian rebel | Babylonian resistance against Sennacherib continued under Mushezib-Marduk, who was defeated after a brief war and a nine-month siege of Babylon. | [16] | |

| Sennacherib destroyed Babylon in 689 BC, hoping to destroy Babylonia as a political entity. The city's reconstruction was announced by his son and successor Esarhaddon in 680 BC. | ||||||

| 110 |  |

Esarhaddon Aššur-aḫa-iddina |

680–669 BC (11 years) |

Son of Sennacherib | Esarhaddon defeated his brother in a civil war and rebuilt Babylon, declaring that the previous destruction of the city was the will of the gods. Esarhaddon invaded Africa, conquering both Egypt and Kush. His reign saw advancement in medicine, literacy, mathematics, architecture and astronomy. | [31] |

| 112 |  |

Shamash-shum-ukin Šamaš-šuma-ukin |

668–648 BC (20 years) |

Son of Esarhaddon, vassal king under Ashurbanipal | Named heir to the Babylonian throne by Esarhaddon, Shamash-shum-ukin resented the overbearing control of his younger brother Ashurbanipal, who was king of Assyria and took care of most of Shamash-shum-ukin's traditional duties as Babylonian king. He revolted against Ashurbanipal in 652 BC and was defeated after a two-year siege of Babylon. | [16][32] |

| 113 | Kandalanu Kandalānu |

648–627 BC (21 years) |

Appointed as vassal king by Ashurbanipal | One of Ashurbanipal's vassals, Kandalanu was placed on the Babylonian throne as his vassal after Shamash-shum-ukin's revolt was defeated. | [16][32] | |

| After Kandalanu's death in 627 BC, Babylonia experienced a brief interregnum. The Neo-Assyrian king Sinsharishkun briefly controlled the city, as did the usurper Sin-shumu-lishir, but both only officially claimed the title "King of Assyria", not "King of Babylon". | ||||||

Eleventh dynasty (626–539 BC)

Also called the Neo-Babylonian dynasty, the Dynasty of Nebuchadnezzar or the Chaldean dynasty, liberated Babylon from Assyrian rule.

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 114 | Nabopolassar Nabû-apla-uṣur |

626–605 BC (21 years) |

Rebel, liberated Babylon from Assyrian rule | Leader of the Chaldean tribe and an accomplished general, Nabopolassar revolted against Sinsharishkun of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and successfully restored Babylonian independence. Through a series of wars Nabopolassar and his allies, the Medes, destroyed the Neo-Assyrian Empire and in its place he founded the Neo-Babylonian Empire. | [33] | |

| 115 |  |

Nebuchadnezzar II Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

605–562 BC (43 years) |

Son of Nabopolassar | Waged numerous wars in the Levant, many of them against Egypt. Famous for the biblical portrayals of his sieges of Jerusalem and for his impressive building projects in Babylon (for instance, the Ishtar Gate). | [33] |

| 116 |  |

Amel-Marduk Amēl-Marduk |

562–560 BC (2 years) |

Son of Nebuchadnezzar II | Unpopular with the priests of Marduk at Babylon, Amel-Marduk's reign was very brief. | [33] |

| 117 | Neriglissar Nergal-šar-uṣur |

560–556 BC (4 years) |

Usurper, son-in-law of Amel-Marduk | A prominent general, recorded as having campaigned in Cilicia in 557 BC, possibly against the Medes. | [33] | |

| 118 | Labashi-Marduk Labaši-Marduk |

556 BC (9 months) |

Son of Neriglissar | A minor when he became king, Labashi-Marduk was deposed and killed after just nine months on the throne. | [33] | |

| 119 |  |

Nabonidus Nabû-naʾid |

556–539 BC (17 years) |

Usurper, unrelated to previous kings | A prominent official of Assyrian background (hailing from Harran), Nabonidus was the last native king to rule Babylon. He alienated the priesthood in Babylon and left the city to reside in Tayma in 552 BC, leaving rule in Babylon itself to his son and designated heir, Belshazzar. Defeated by Cyrus of the Achaemenid Empire in 539 BC, ending the Neo-Babylonian Empire. | [33] |

Post-Neo-Babylonian kings

Babylonia was conquered by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire in 539 BC, to never again successfully regain independence. The monarchs of the Achaemenid Empire, and those of succeeding empires, continued to title themselves (and be titled by the inhabitants of Babylon) as Kings of Babylon for centuries. The Akkadian names of the monarchs listed after Nabonidus follow the renderings of the names of these monarchs in the Uruk King List (also known as "King List 5") and the Babylonian King List of the Hellenistic Period (also known as BKLHP or “King List 6”).[34] These lists records rulers, identifying them as "Kings of Babylon" until the end of Seleucid rule in Mesopotamia.[35]

Achaemenid dynasty (539–331 BC)

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120 |  |

Cyrus the Great Kur-aš |

539–530 BC (9 years) |

King of Persia, conquered Babylon | The first king of the Achaemenid Empire, Cyrus the Great captured Babylon in 539 BC. In Babylon he left the famous Cyrus Cylinder. Enumerated as Cyrus II as King of Persia. | [34] |

| 121 |  |

Cambyses Kambu-zī |

530–522 BC (8 years) |

Son of Cyrus the Great | Famous for conquering Egypt and for the unpopular policies he conducted in the country (looting temples and ridiculing the local gods). Had served as governor in Babylonia under Cyrus for some years. Enumerated as Cambyses II as King of Persia. | [34][36] |

| 122 | Darius I the Great Daria-muš |

522–486 BC (36 years) |

Son of Hystaspes, a third cousin of Cyrus the Great. | Darius was briefly preceded as Achaemenid king by Bardiya, who was not recorded as king by the Babylonians. His early reign saw rebellions against his rule by the Babylonians, perhaps inspired by the recent political turmoil in the empire. | [34] | |

| 123 |  |

Nebuchadnezzar III Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

522 BC (less than a year) |

Babylonian rebel, claimed to be the son of Nabonidus | Rebelled against Darius I. Originally called Nidintu-Bêl, Nebuchadnezzar claimed to be the son of Nabonidus and was probably connected to Babylonian royalty in some form. Was defeated and executed after Darius besieged Babylon. | [37] |

| 124 |  |

Nebuchadnezzar IV Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

521–520 BC (1 year) |

Babylonian rebel, claimed to be the son of Nabonidus | Rebelled against Darius I. Originally an Armenian by the name Arakha, Nebuchadnezzar IV also claimed to be the son of Nabonidus. Darius's second siege of Babylon lasted more than a year and seven months before he successfully regained control of the city. | [38] |

| 125 |  |

Xerxes the Great [Full name in Akkadian not preserved] |

486–465 BC (23 years) |

Son of Darius I | Up until Xerxes's time, the Achaemenid rulers had regarded Babylon as a separate entity united with their own kingdom in a personal union, but in response to the second Babylonian revolt against him, Xerxes removed the statue of Marduk in the Esagila and divided the Babylonian satrapy (previously composing almost all of the Neo-Babylonian Empire's territory) into smaller satrapies. Enumerated as Xerxes I as King of Persia. | [39] |

| 126 | Bel-shimanni Bêl-šimânni |

484 BC (2 weeks) |

Babylonian rebel | Rebelled against Xerxes in June or July 484 BC. Bel-shimanni's revolt was probably short-lived as Babylonian documents relating to his rule only cover a period of about two weeks. | [40] | |

| 127 | Shamash-eriba Šamaš-eriba |

482–481 BC (c. 8 months) |

Babylonian rebel | Rebelled against Xerxes in the summer of 482 BC. Shamash-eriba's rebellion lasted longer than that of Bel-shimmani and Babylon was successfully retaken by Xerxes in March 481 BC, after which the city was reprimanded through a destruction of its fortifications and possible devastation done to its temples. Because Xerxes's vengeance, Shamash-eriba was the last person to be crowned in the traditional Babylonian manner; receiving the Babylonian crown out of the hands of Marduk at the Esagila temple during the New Year's Festival. | [40] | |

| 128 |  |

Artaxerxes I Longimanus [Full name in Akkadian not preserved] |

465–424 BC (41 years) |

Son of Xerxes | Because Xerxes' attempt to end Babylonia as a separate entity, kings from Artaxerxes I onwards (other than rebel leaders) didn't use the title King of Babylon themselves, though Babylonian scribes continued to refer to them as such. | [39] |

| 129 |  |

Darius II Daria-muš |

423–404 BC (19 years) |

Son of Artaxerxes I | Darius II was briefly preceded as Achaemenid king by Xerxes II, who was only recognized in Persia itself, and Sogdianus, who was only recognized in Persia and Elam (neither was recognized in Babylon). | |

| 130 |  |

Artaxerxes II Mnemnon [Full name in Akkadian not preserved] |

404–358 BC (46 years) |

Son of Darius II | Was faced with the revolt of his brother Cyrus the Younger, which he defeated, wars with the Greeks and the Great Satraps' Revolt. | |

| 131 |  |

Artaxerxes III Ochus [Full name in Akkadian not preserved] |

358–338 BC (20 years) |

Son of Artaxerxes II | Successfully regained Egypt after it had revolted against Persian rule after the death of Darius II. Also had to deal with revolts from numerous satrapies and vassal states. | |

| 132 |  |

Artaxerxes IV Arses [Full name in Akkadian not preserved] |

338–336 BC (2 years) |

Son of Artaxerxes III | Poisoned and killed by the eunuch Bagoas, who also killed the entirety of his family and put Darius III on the throne of the Achaemenid Empire. | [41] |

| 133 | Nidin-Bel Nidin-Bêl |

c. 336 BC (less than a year) |

Babylonian rebel | Mentioned only in the Uruk King List, Nidin-Bel was likely a local rebel who seized control in the chaotic aftermath of Artaxerxes IV's death, only to later be defeated by Darius III. | [34] | |

| 134 |  |

Darius III Daria-muš |

336–331 BC (6 years) |

Great-grandson of Darius II | Darius III was the last (or penultimate if one counts Artaxerxes V) king of the Achaemenid Empire and was defeated by Alexander the Great of Macedon after reigning only six years. | [34] |

Argead dynasty (331–309 BC)

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 135 |  |

Alexander I the Great Aliksāndar |

331–323 BC (8 years) |

King of Macedon, conquered Babylon | Alexander captured most of the territory of the Achaemenid Empire in his famous wars. Under Alexander, Babylon once more became an imperial capital, being the main capital of his large empire. Enumerated as Alexander III as King of Macedon. | [34][42] |

| 136 |  |

Philip Arrhidaeus Pīlipsu |

323–317 BC (6 years) |

Brother of Alexander the Great | The elder half-brother of Alexander, Philip suffered from learning difficulties and was proclaimed king as a figurehead in Macedon. Enumerated as Philip III as King of Macedon. | [34] |

| 137 | Alexander II Aliksāndar |

323–309 BC (14 years) |

Son of Alexander the Great | Alexander the Great's posthumous son, Alexander Aegus was recognized as his successor throughout the empire. Alexander Aegus is listed as king between Antigonus and Seleucus I in King List 6. Enumerated as Alexander IV as King of Macedon. | [35] | |

| 138 | .jpg) |

Antigonus Monophthalmus Attugūn |

317–311 BC (6 years) |

Macedonian general | A Macedonian general and one of the Diadochi, Antigonus is recorded as the king between Philip Arrhidaeus and Seleucus I in King List 5. Babylonian sources suggest that his rule was considered illegal and that he should have accepted the sovereignty of Alexander's son Alexander. | [34][35] |

Seleucid dynasty (311–141 BC)

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 139 | Seleucus I Nicator Silukku |

311–281 BC (31 years) |

Macedonian general | Seleucus only proclaimed himself king in 305 BC, but the Babylonians dated his reign from 311 BC. After becoming king, Seleucus moved the capital of his empire to the newly built city Seleucia. Most of the Greek citizens in Babylon, having settled there after Alexander's conquests, moved to the new city. | [34][42] | |

| 140 |  |

Antiochus I Soter Anti'ukusu |

281–261 BC (22 years) |

Son of Seleucus I | The last ruler to be attributed the ancient Mesopotamian title of King of the Universe, Antiochus I was the last monarch from which a full Akkadian royal titulary is known, presented in the Antiochus Cylinder. | [34][43] |

| 141 |  |

Antiochus II Theos Anti'ukusu |

261–246 BC (15 years) |

Son of Antiochus I | No activities recorded from Babylon. Antiochus II's reign saw war against Egypt and revolts from vassals in the eastern parts of his empire. | [34] |

| 142 | %2C_Antioch_mint.jpg) |

Seleucus II Callinicus Silukku |

246–225 BC (21 years) |

Son of Antiochus II | No activities recorded from Babylon. Seleucus II's reign saw continued political turmoil and fragmentation. Ptolemy III of Egypt invaded his kingdom and almost reached Babylon. | [34] |

| 143 |  |

Seleucus III Ceraunus Silukku |

225–223 BC (2 years) |

Son of Seleucus II | No activities recorded from Babylon. Seleucus III's reign was brief and marred with unsuccessful wars against Pergamon. | [35] |

| 144 | %2C_late_1st_century_BC%E2%80%93early_1st_century_AD%2C_Louvre_Museum_(7462828632).jpg) |

Antiochus III the Great Anti'ukusu |

222–187 BC (35 years) |

Son of Seleucus II | Present at Babylon at the time he was proclaimed king, Antiochus III was one of the Seleucid Empire's greatest kings. He is recorded as having resettled two thousand Jewish families from Babylonia into the Hellenistic regions of Lydia and Phrygia. | [35] |

| 145 |  |

Seleucus IV Philopator Silukku |

187–175 BC (8 years) |

Son of Antiochus III | No activities recorded from Babylon. Seleucus IV was plagued by financial difficulties owing to war reparations to be paid to the Romans. | [35] |

| 146 |  |

Antiochus IV Epiphanes Anti'ukusu |

175–164 BC (11 years) |

Son of Antiochus III | Antiochus IV introduced a new colony of Greek citizens in Babylon. These Greeks were recognized by the Babylonians themselves as a separate community in the city (called pulitē, a rendering of the Greek word politai, "citizen"). | [35][42] |

| 147 |  |

Antiochus V Eupator Anti'ukusu |

164–161 BC (3 years) |

Son of Antiochus IV | No activities recorded from Babylon. Antiochys V, a minor, was crowned despite the fact that Demetrius I (his successor) was generally recognized as the rightful king because Demetrius was in Roman captivity at the time. Once Demetrius escaped he was proclaimed king and Antiochus V was executed. | |

| 148 |  |

Demetrius I Soter [Full name in Akkadian not preserved] |

161–150 BC (11 years) |

Son of Seleucus IV | Demetrius I was given his nickname Soter (meaning "saviour") by the population of Babylonia because he had defeated the usurper Timarchus who had attempted to seize control of the region. | [35][44] |

| 149 |  |

Alexander III Balas Aliksāndar |

150–145 BC (5 years) |

Usurper, allegedly the son of Antiochus IV | No activities recorded from Babylon. A usurper of uncertain relation, Alexander Balas seized the Seleucid throne from Demetrius I, but would only rule for five years before in turn being defeated by Demetrius II. | |

| 150 | %2C_Ptolemais_in_Phoenicia_mint.jpg) |

Demetrius II Nicator [Full name in Akkadian not preserved] |

145–141 BC (4 years) |

Son of Demetrius I | Lost control of Babylonia to the Parthians, Demetrius II is the final ruler to be listed in King List 6. | [35] |

King List 6 ends, after Demetrius II, with a passage referencing "Arsaces the king"[n 1], indicating that the list was created in the early years of Parthian rule in Mesopotamia. Because the list is so fragmentary, it isn't clear if this Arsaces was formally considered a King of Babylon (as the Persian and Hellenic rulers had been) by the list's author.[45]

Arsacid dynasty and final kings of Babylon (141–80 BC)

Under the rule of the Parthian Empire, Babylon was gradually abandoned as a major urban center and the old Akkadian culture diminished. In the first century or so of Parthian rule, Babylonian culture was still alive, and there are records of individuals in the city with traditional Babylonian names, such as Bel-aḫḫe-uṣur and Nabu-mušetiq-uddi (mentioned as the receivers of silver in a 127 BC legal document).[46] At this time, there were two major recognized groups living in Babylon: the Babylonians themselves and the Greeks, having settled there during the centuries of Argead and Seleucid rule. These groups were governed by separate local (e.g. pertaining to just the city) administrative councils; the Babylonian citizens were governed by the šatammu and the kiništu and the Greeks by the epistates. Although no king lists younger than King List 6 are known, documents from the early years of Parthian rule suggest a continued recognition of at least the early Parthian kings as Babylonian monarchs.[47]

| No. | Image | King | Reign | Succession | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 151 |  |

Mithridates I the Great Aršáka |

141–132 BC (9 years) |

King of Parthia, conquered Babylon | Babylonian records from Mithridates I's reign mention that within two months of the Parthian conquest, Babylonian authorities were summoned to Hyrcania, Parthia's heartland, and new functionaries were appointed in the city. | [48] |

| 152 | %2C_Seleucia_mint.jpg) |

Phraates Aršáka |

132–130 BC (2 years) |

Son of Mithridates I | Lost control of Babylon to the Seleucids in 130 BC after a series of battles and died in 127 BC. Enumerated as Phraates II as King of Parthia. | [49] |

| From 130 to 127 BC, the Seleucids once more controlled Babylon but there are no references to them as Babylonian kings in Babylonian documents from this time. | ||||||

| 153 | Hyspaosines Aspa-asinē |

127 BC (a few months) |

Seleucid satrap | A former Seleucid satrap, Hyspaosines proclaimed himself king, becoming the first king of Characene in 141 BC, a Parthian vassal kingdom. He was recognized as "King of Babylon" by the Babylonians for a few months in 127 BC after he captured the city. He is recorded as having gifted a "throne" to the god Bel in the temple Esagila, indicating the continued presence of old Mesopotamian religious institutions. | [50] | |

| 154 | %2C_Seleucia_mint.jpg) |

Artabanus Aršáka and Ártabana |

127–124 BC (3 years) |

Brother of Mithridates I | Artabanus's reign was a period of turmoil in the Parthian Empire, which saw a weakening of central control. Most of his brief reign was spent fighting nomads in the east. Enumerated as Artabanus I as King of Parthia. | [51] |

| 155 | %2C_Ecbatana_mint.jpg) |

Mithridates II the Great Aršáka |

124–91 BC (3 years) |

Son of Artabanus | Babylonian records from Mithridates II's reign tell that the Babylonians were called upon to aid in building projects in Seleucia. The kiništu is mentioned, indicating that it was still functioning. | [52] |

| 156 | %2C_Ectbatana_mint.jpg) |

Gotarzes Aršáka and Gutárza |

91–87 or 80 BC (4 or 11 years) |

Son of Mithridates II | Proclaimed as King at Babylon during a period of turmoil in the Parthian Empire. Gotarzes is the last known ruler to be mentioned as Babylonian king in Akkadian-language documents. Enumerated as Gotarzes I as King of Parthia. | [53][54] |

Notes

- Arsaces was the regnal name used by all Parthian kings. The Parthian king who succeeded Demetrius II as the ruler of Mesopotamia was Mithridates I.

References

- BM 33332.

- BM 38122.

- The text is in a private collection and was published in: Arno Poebel (1955). "Second Dynasty of Isin According to a New King-List Tablet". Assyriological Studies. University of Chicago Press (15).

- Meissner, Bruno (1990). Reallexikon der Assyriologie. 6. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 90. ISBN 3-11-010051-7.

- Kuhrt 1997, p. 12.

- Mieroop 2015, p. 4.

- Sagona & Zimansky 2009, p. 251.

- Chronology.

- "T12K1.htm". cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- "T12K2.htm". cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- Year names of Sabium of Babylon - CDLI

- Year names of Sabium of Babylon - CDLI

- A history of Babylonia and Assyria, Volume 1, Robert William Rogers, Eaton & Mains, 1900. pp. 387-388.

- Beck, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C.; Shabaka, Dahia Ibo (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 978-0-395-87274-1. OCLC 39762695.

- Brinkman 1976, pp. 97–98.

- Synchronic King List.

- Mieroop 2015, p. 355.

- J. A. Brinkman (1976). "* Meli-Šipak". Materials and Studies for Kassite History, Vol. I (MSKH I). Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 253–259.

- Brinkman 1999, pp. 183–184.

- Mieroop 2015, p. 356.

- Meissner 1999, p. 8.

- Brinkman 1982, pp. 296–297.

- J. A. Brinkman (1982). "Babylonia, c. 1000 – 748 B.C.". In John Boardman; I. E. S. Edwards; N. G. L. Hammond; E. Sollberger (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History (Volume 3, Part 1). Cambridge University Press. pp. 296–297.

- Tremper Longman (July 1, 1990). Fictional Akkadian autobiography: a generic and comparative study. Eisenbrauns. pp. 153–154, 161.

- Tablet YBC 11546 in the Yale Babylonian Collection.

- Dynastic Chronicle (ADD 888) vi 3’-5’.

- J. A. Brinkman (1968). A political history of post-Kassite Babylonia, 1158-722 B.C. Analecta Orientalia. pp. 221–224.

- Karen Radner; Eleanor Robson (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture. Oxford University Press. p. 740.

- Tadmor 1994, p. 29.

- Frye, Wolfram & Dietz 2016.

- Mark 2014.

- Johns 1913, p. 124–125.

- The Latin Library.

- Uruk King List.

- CM 4.

- Dandamayev 1990, pp. 726-729.

- Holland 2007, p. 46.

- Herodotus III, 152

- Dandamaev 1989, pp. 185–186.

- Dandamaev 1993, p. 41.

- LeCoq 1986, p. 548.

- Spek 2001, p. 446.

- Stevens 2014, p. 72.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911, p. 983.

- Sachs & Wiseman 1954, p. 209.

- Spek 2001, p. 449.

- Spek 2001, p. 451.

- Spek 2001, p. 450.

- Shayegan 2011, pp. 128-129.

- Spek 2001, pp. 452–453.

- Schippmann 1986a, pp. 647–650.

- Spek 2001, p. 454.

- Spek 2001, p. 455.

- Assar 2006, p. 62.

Cited bibliography

- Assar, Gholamreza F. (2006). A Revised Parthian Chronology of the Period 91-55 BC. Parthica. Incontri di Culture Nel Mondo Antico. 8: Papers Presented to David Sellwood. Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali. ISBN 978-8-881-47453-0. ISSN 1128-6342.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brinkman, J. A. (1976). Materials and Studies for Kassite History, Vol. I (MSKH I). Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1982). "Babylonia, c. 1000 – 748 B.C.". The Cambridge Ancient History (Volume 3, Part 1). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521224963.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1999). Reallexikon Der Assyriologie Und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie (Vol 5): Ia – Kizzuwatna. Walter De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-007192-4.

- Dandamaev, Muhammad A. (1989). A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004091726.

- Dandamaev, Muhammad A. (1993). "Xerxes and the Esagila Temple in Babylon". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 7: 41–45. JSTOR 24048423.

- Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (1990). "Cambyses II". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 7. pp. 726–729.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11 ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1911.

- Frye, Richard N.; Wolfram, Th. von Soden; Dietz, O. Edzard (15 April 2016). "History of Mesopotamia". Encyclopædia Britannica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- George, Andrew (2007). "Babylonian and Assyrian: A history of Akkadian" (PDF). The Languages of Iraq: 31–71.

- Holland, Tom (2007). Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 9780307386984.

- Johns, C. H. W. (1913). Ancient Babylonia. Cambridge University Press. p. 124.

Shamash-shum-ukin.

- Kuhrt, A. (1997). Ancient Near East c. 3000–330 BC. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16763-5.

- Lipschits, Oled (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah under Babylonian Rule. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060958.

- LeCoq, P. (1986). "Arses". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. p. 548.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meissner, Bruno (1999). Reallexikon Der Assyriologie Und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie: Meek - Mythologie. Walter De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-014809-1.

- Van Der Mieroop, Marc (2015). A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1405149112.

- Sachs, A. J.; Wiseman, D. J. (1954). "A Babylonian King List of the Hellenistic Period". Iraq. 16 (2): 202–212. doi:10.2307/4199591. JSTOR 4199591.

- Sagona, A.; Zimansky, P. (2009). Ancient Turkey. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-28916-0.

- Schippmann, K. (1986a). "Artabanus (Arsacid kings)". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. pp. 647–650.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2011). Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–539. ISBN 9780521766418.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van der Spek, R. J. (2001). "The Theatre of Babylon in Cuneiform". Veenhof Anniversary Volume: Studies Presented to Klaas R. Veenhof on the Occasion of His Sixty-fifth Birthday: 445–456.

- Stevens, Kahtryn (2014). "The Antiochus Cylinder, Babylonian Scholarship and Seleucid Imperial Ideology" (PDF). The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 134: 66–88. doi:10.1017/S0075426914000068. JSTOR 43286072.

- Tadmor, Hayim (1994). The Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III, King of Assyria: Critical Edition, with Introductions, Translations, and Commentary. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Cited web sources

- "A Brief Chronology of Ancient Near Eastern History". Hixenbaugh Ancient Art. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Lendering, Jona (2005). "Uruk King List". Livius. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- van der Spek, Bert (2004). "CM 4 (Babylonian King List of the Hellenistic Period)". Livius. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "Synchronic King List". Livius. 2006. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "The Chaldean Empire (625 - 539 B.C.)". The Latin Library. Retrieved 8 December 2019.