Latino-Faliscan languages

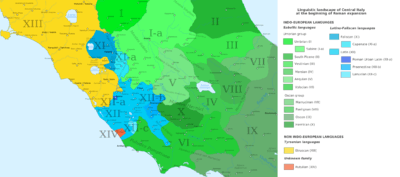

The Latino-Faliscan or Latino-Venetic languages are a group of languages spoken by the Latino-Faliscan people of Italy beginning 1200 BC, belonging to the Italic languages, and are a group of the Indo-European languages.

| Latino-Faliscan | |

|---|---|

| Latinian | |

| Geographic distribution | Originally Latium in Italy, at maximum extent as a living language, throughout the Roman Empire, especially in western regions. |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Latino-Faliscan (Praeneste fibula) |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | lati1262[1] |

Latino-Faliscan languages and dialects in different shades of blue. | |

Latin and Faliscan belong to the group as well as two others often considered to be archaic Latin dialects: Lanuvian and Praenestine.

Latin eventually absorbed ideas from the others and replaced Faliscan as the power of Ancient Rome grew. All of the other languages other than Latin went extinct as Latin became dominant. Latin, in turn, via Vulgar Latin, developed into the numerous Romance languages, which are now spoken by more than 800 million people worldwide, largely due to the influence of the French, Spanish and Portuguese Empires.

Linguistic description

Latin and Faliscan have several innovations with Italic:

- The late Indo-European sequences /*ə, *eu/ evolve into a, ou.

- The Indo-European syllabic liquids /*l̥, *r̥/ develop an epenthetic vowel o giving in Italic ol, or.

- The Indo-European syllabic nasals /*m̥, *n̥/ develop an epenthetic vowel e giving em, en.

- Fricativisation of aspirated stops of Indo-European at the beginning of the word /*bʰ, *dʰ, *gʰ/ into f, f, h.

- Assimilation of the sequence /*kʷ...p/ into kʷ...kʷ (Proto-Indo-European *penkʷe 'five' > Latin quinque)

Some differences are that Latin and Faliscan retain the Indo-European labiovelars /*kʷ, *gʷ/ as qu-, gu- (they would later become velars + semivocal), while in Osco-Umbrian, they become labial p, b. In addition, Latin also shows the evolution of ou into ū (Latin lūna < Proto-Italic *louksnā < PIE *lówksneh₂ "moon").

A morphological innovation shared by Latin and Faliscan is the use of the accusative suffix -d, seen in med ("me", accusative), which is not present in Osco-Umbrian.

Phonology

The consonant inventory of Proto-Latino-Faliscan would be basically identical to that of archaic Latin. Consonants not found in the Praeneste fibula are marked with an asterisk:

Labial Alveolar Palatal Velar Labio-

velarGlottal Plosives voiceless *p *t k *kʷ voiced *b d *g *gʷ Fricative f s *h Sonorants *r, *l j *w Nasal m n

The /kʷ/ sound still had to exist in archaic Latin when the alphabet was developed where the minimum pair comes from: quī /kʷī/ ("who", nominative) - cuī /ku.ī/ ("to whom", dative). Note that in other positions no attempt is made to distinguish between diphthongs and hiatuses: persuādere ("to persuade") is a diphthong but sua ("his"/"her") is a hiatus. For reasons of symmetry, it is quite possible that many sequences of gu in archaic Latin will in fact represent a voiced labiovelar /gʷ/.

Description

Initially, the Indo-Europeanists had been inclined to postulate a belonging to a unitary linguistic family for the various Indo-European languages of ancient Italy, parallel to that of Celtic or Germanic; the founder of this hypothesis is considered Antoine Meillet (1866–1936).[2]

Starting from the work of Alois Walde (1869–1924), however, this unitary scheme has been subjected to radical criticism; decisive, in this sense, were the arguments put forward by Vittore Pisani (1899–1990) and, later also by Giacomo Devoto (1897–1974), who postulated the existence of two distinct Indo-European branches in which it is possible to inscribe the Italic languages. Variously reformulated in the years following the Second World War, the various hypotheses concerning the existence of two different Indo-European families have definitively imposed themselves, even if the specific traits that separate or close them, as well as the exact processes of formation and penetration into Italy, remain the object of research by historical linguistics.[3]

The Latino-Faliscan languages were:[3]

- Faliscan, spoken in the area around Falerii Veteres (the modern Civita Castellana) north of the city of Rome.

- Latin, spoken in central-western Italy, later spread (in the specific version of Latin spoken in Rome) with the Roman conquests throughout the Empire and beyond.

- Venetic, spoken in northeastern Italy by the Veneti (possibly Celtic, transitional or independent).

- Sicel, spoken in eastern Sicily by the Sicels (limited attestation; possibly not Italic).

See also

References

- Villar, Francisco (1997). Gli Indoeuropei e le origini dell'Europa [Indo-Europeans and the origins of Europe] (in Italian). Bologna, Il Mulino. ISBN 88-15-05708-0.

- Vineis, Edoardo (1995). "X. Latin". In Giacolone Ramat, Anna; Ramat, Paolo (eds.). Las lenguas indoeuropeas [The Indo-European languages] (in Spanish). Madrid: Cátedra. pp. 349–421. ISBN 84-376-1348-5.

Notes

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Latino-Faliscan". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Villar, 'Gli Indoeuropei e le origini dell'Europa, pp. 474-475.

- Villar, cit., pp. 447-482.

Further reading

| Library resources about Latino-Faliscan languages |

- Bakkum, Gabriël C. L. M. 2009. The Latin Dialect of the Ager Faliscus: 150 Years of Scholarship. Part 1. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Baldi, Philip. 2002. The foundations of Latin. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Clackson, James, and Geoffrey Horrocks. 2007. The Blackwell history of the Latin language. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Giacomelli, Roberto. 1979. "Written and spoken language in latin-faliscan and greek-messapic." Journal of Indo-European Studies 7 no. 3–4: 149-75.

- Mercado, Angelo. 2012. Italic Verse: A Study of the Poetic Remains of Old Latin, Faliscan, and Sabellic. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen der Universität Innsbruck.

- Palmer, Leonard R. 1961. The Latin language. London: Faber and Faber.

- Joseph, Brian D., and Rex E. Wallace. 1991. "Is faliscan a local latin patois?" Diachronica: International Journal for Historical Linguistics/Revue Internationale Pour La Linguistique Historiqu 8, no. 2: 159-86.