Kingston, Queensland

Kingston is a town and suburb in the City of Logan, Queensland, Australia.[2][3] In the 2016 census, Kingston had a population of 10,539 people.[1]

| Kingston Logan City, Queensland | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Marsden library is located in the far south of the suburb | |||||||||||||||

Kingston | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 27.6566°S 153.1177°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 10,539 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 1,573/km2 (4,074/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 4114 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 6.7 km2 (2.6 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10:00) | ||||||||||||||

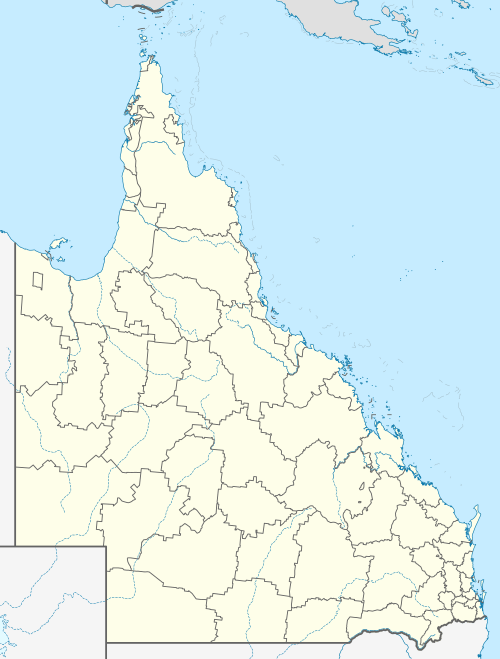

| Location |

| ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | Logan City | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Federal Division(s) | Rankin | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Geography

Kingston is a predominantly residential suburb, with a low mix of industrial, commercial and retail areas. At the 2016 census, the suburb recorded a population of 10,539.[1] The suburb is bounded in the south by Scrubby Creek, a tributary of the Logan River. It is the home of the Kingston Butter Factory. Kingston was also the site of an environmental disaster similar to Love Canal in Niagara Falls in the United States.

History

The township was named Kingston in 1890 Charles and Harriet Kingston, who were residents of the district in the late nineteenth century.[2][3]

Like a number of other Logan City suburbs Kingston was once part of the Shire of Tingalpa.[4] Dairying grew in importance in the area from the 1890s and in 1906 a meeting was held in Beenleigh to form a co-operative butter factory locally. The Southern Queensland Co-operative Dairy Company opened its factory in Kingston in June 1907. A piggery was established nearby in 1926 and pigs were fed on the buttermilk from the factory. The Kingston Butter Factory was enlarged in 1932 and operated successfully until after the war, when the dairying industry was being rationalised by the government. Peters bought the factory in 1958 and it ceased production in 1983. It now operates as a community arts centre and houses a theatre, arts and crafts stall and museum.[5] The Kingston Butter Factory is on the Logan City Council Local Heritage Register for its historical, social and technological significance.[6]

In October 1885, 72 subdivided blocks of land named "Kingston Railway Station Estate" were advertised to be auctioned by John W Todd.[7] A map advertising the auction shows that the blocks were close to Kingston Railway Station and a selling feature of the estate was the extensive and picturesque views.[8]

Kingston State School opened on 8 July 1912.[9]

The other major industrial activity of the area was the Kingston gold mine at Mount Taylor. Although gold was discovered in 1885, a geological survey was not undertaken until 1913 and underground mining began. In 1932, the Kingston Gold Mining Company began an open cut operation and mining continued until 1954. The area became an unofficial waste dump. It was eventually backfilled and subdivided into a housing estate in the late 1960s.[10]

Kingston State Infants School opened on 27 January 1976. It closed on 17 December 1993.[9]

Kingston State High School was established in Bega Road on 24 January 1977. It was officially opened by the Minister for Education, Val Bird.[11] Its students come mainly from the residential suburbs of Kingston, Marsden, Browns Plains, Loganlea, and Woodridge. On 1 November 1999 it was renamed Kingston College.[9]

Kingston Centre for Continuing Secondary Education opened on 4 February 1991.[9]

The Centre Education Programme opened on 1 July 1997.[9]

Groves Christian College opened on 1999. It opened its Maryfields primary campus on 21 January 2005.[9]

In the 2016 census, Kingston had a population of 10,539 people.[1]

Kingston toxic waste

The Kingston toxic waste story began in 1931 when cyanide and other toxins such as acid waste used in the Mount Taylor gold refining process were disposed of around the mine site. When the mine closed in 1954, the Albert Shire Council started to allow used recycled oil processing wastes to be dumped into a sludge pit on the site; this practice continued until 1967. From 1968 to 1973 the main open-cut pit was used as a domestic and industrial waste tip. In 1968 the council required the sludge pit to be filled as a condition of the land being divided for a residential subdivision. Workers simply moved the displaced sludge and re-dumped it into the open-cut pit.[12]

In 1982, after the Logan Council took over the area, it discovered high levels of acid in the soil.

In September 1986 residents, in the Diamond street area of Kingston, started to notice black sludge beginning to ooze from the ground and seep into their gardens and began to complain of health problems to the Logan Council.[13]</ref> By April 1987 the council was warning people to avoid the sludge. Surrounding soils and ground-water were also found to be contaminated.

In May 1987, frustrated with the council inaction, the residents of Kingston formed an organisation called RATS (Residents Against Toxic Substances). Because of increased leukaemia and other diseases in Kingston, they condemned the council and demanded action. Kingston residents could not afford a costly civil action so they went to the media and began a self-funded civic action.[12]

It took four years of fighting the council and local governments for the residents of Kingston to be vindicated when the Minister for Emergency Services, Terry Mackenroth, ordered a review of all scientific and medical evidence, offered full health tests for residents and announced the Wayne Goss government would rehabilitate the site and pay for families to be moved away.

Eventually the state government resumed 46 properties and rehabilitated the area completing 1991, which is known as Kingston Park.[13] The people of Kingston were moved on, Mount Taylor was sealed and landscaped, but no compensation came for residents who reported illnesses and deaths (Some place the figure at six deaths due to leukemia).[12] The final medical report found no evidence of "a major toxic hazard" in Kingston but recognised the "stress on a number of residents because of the uncertainty". Kingston residents finally could not prove that dumped toxic chemicals caused leukaemia or any other disease.

The total cost of this operation to date, including relocating infrastructure, the engineering required to seal the site and ongoing monitoring, is approximately $8 million. (pg6)[14] Although the Mount Taylor site was capped, sealed and vented in 1991, no toxic waste was removed. Some former residents believe there is still a toxic hazard risk in the future as a result.[12]

Heritage listings

Kingston has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

- Bega Road: Kingston Pioneer Cemetery[15]

- 36 Mawarra Street: Mayes Cottage[16]

Demographics

According to the 2016 census of Population, there were 10,539 people in Kingston.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people made up 5.9% of the population.

- 55.4% of people were born in Australia. The next most common countries of birth were New Zealand 9.2%, Samoa 2.1%, England 2.1%, Myanmar 1.7% and Afghanistan 1.4%.

- 64.0% of people spoke only English at home. Other languages spoken at home included Samoan 4.1%, Karen 2.2%, Hindi 1.2%, Hazaraghi 1.1% and Arabic 1.1%.

- The most common responses for religion were No Religion 25.4% and Catholic 14.3%.

- The median age of the Kingston population was 31 years, 7 years below the national median of 38.[1]

Transport

Kingston railway station provides access to regular Queensland Rail City network services to Brisbane and Beenleigh. The Logan Motorway passes through the south of Kingston but has no entrance or exit points to the suburb.

Education

Kingston State School is a government primary (Prep-6) school for boys and girls at 50 Juers Street (27.6594°S 153.1115°E).[17][18] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 620 students with 48 teachers (44 full-time equivalent) and 34 non-teaching staff (22 full-time equivalent).[19] It includes a special education program.[17]

Groves Christian College is a private primary and secondary (Prep-12) school for boys and girls at 70 Laughlin Street (27.6609°S 153.1099°E).[17][20] Its has its Maryfield primary (4-6) campus at Velorum Drive (27.6604°S 153.0988°E).[17][20] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 1,391 students with 103 teachers (89 full-time equivalent) and 63 non-teaching staff (56 full-time equivalent).[19]

Kingston State College is a government secondary (7-12) school for boys and girls at 62-84 Bega Road (27.6641°S 153.1121°E).[17][21] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 876 students with 94 teachers (82 full-time equivalent) and 45 non-teaching staff (34 full-time equivalent).[19] It includes a special education program.[17]

The Centre Education Programme is a Catholic secondary (7-12) school for boys and girls at 108 Mudgee Street (27.6679°S 153.1103°E).[17][22] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 118 students with 15 teachers (10 full-time equivalent) and 14 non-teaching staff (9 full-time equivalent).[19]

YMCA Vocational School is a private secondary (7-10) facility of YMCA Vocational School at 41-45 Mary Street for boys and girls at 53 Mary Street (27.6571°S 153.1225°E).[17][23] In 2017, the school had an enrolment of 327 students with 21 teachers (19 full-time equivalent) and 35 non-teaching staff.[19]

Kingston Centre for Continuing Secondary Education is a secondary (9-12) Centre for Continuing Secondary Education at 62-84 Bega Road (27.6641°S 153.1121°E).[17][24]

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Kingston (SSC)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Kingston - town in City of Logan (entry 18245)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Kingston - suburb in City of Logan (entry 50312)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Mary Howells. "Mount Cotton - a brief history" (PDF). Redland City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- A Brief history of Logan

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Classified Advertising". The Brisbane Courier. XL (8, 668). Queensland, Australia. 24 October 1885. p. 7. Retrieved 29 May 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Kingston Railway Station Estate". 29 May 2019. hdl:10462/deriv/18468. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Queensland Family History Society (2010), Queensland schools past and present (Version 1.01 ed.), Queensland Family History Society, ISBN 978-1-921171-26-0

- Buchanan 1999, page 57

- "Opening and closing dates of Queensland Schools". Queensland Government. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Real Estate Blog - Australia". Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Buchanan 1999, page 4}}

- SL 2000 No. 178RIS No. 2

- "Kingston Pioneer Cemetery (entry 601495)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Mayes Cottage (entry 600662)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "State and non-state school details". Queensland Government. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Kingston State School". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "ACARA School Profile 2017". Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Groves Christian College". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Kingston State College". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "The Centre Education Programme". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "YMCA Vocational School". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Kingston Centre for Continuing Secondary Education". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

Bibliograpy

- Buchanan, Robyn (1999). "Mining". Logan: Rich in History, Young in Spirit (PDF). Logan City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kingston, Queensland. |

- "Kingston". Queensland Places. Centre for the Government of Queensland, University of Queensland.

- "Town map of Kingston". Queensland Government. 1976.

- "A brief history of Logan".

- "A history of Mining in Logan" (PDF).

- "Logan City map" (PDF).

- "Pictures of the Kingston mine circa 1960s".