Kingdom of Larantuka

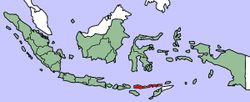

The Kingdom of Larantuka was a kingdom in present-day East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. It was the one of the few, if not the only, indigenous Roman Catholic polities in the territory of modern Indonesia. Acting as a tributary state of the Portuguese Crown, the Raja (King) of Larantuka controlled holdings on the islands of Flores, Solor, Adonara and Lembata. It was later purchased by Dutch East Indies from the Portuguese, prior to its annexation in 1904.[1]

Kingdom of Larantuka Ilimandiri Larantuka Kerajaan Larantuka | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1515–1904 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Status | Tributary state of the Portuguese Empire | ||||||

| Capital | Larantuka | ||||||

| Common languages | Larantuka Malay Li'o | ||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Portuguese arrival | 1515 | ||||||

• Conversion to Roman Catholicism | 1650 | ||||||

• Purchase by Dutch East Indies | 1859 | ||||||

• Disestablished | 1 July 1904 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | |||||||

Despite losing its effective sovereignty after the annexation, the Kingdom's royal family persisted as traditional figureheads prior to the final abolition of the royal structure by republican authorities in 1962.[2]:175

History

Monarchs of the Larantuka Kingdom claim descent from a union between a man from the Kingdom of Wehale Waiwuku in South Timor and a mythical woman from a nearby extinct volcano of Ile Mandiri. Traditional belief systems and rituals of the Lamaholot people who were their subjects place the rajas in a central role, especially for those who adhered to traditional beliefs.[1][3]:72–74

In the Javanese Negarakertagama, the locations Galiyao and Solot were mentioned to be "east of Bali" and are believed to correspond to the approximate region, indicating some form of contact from tributary relations or trading between the region and the Majapahit Empire, due to its location in the trade routes carrying sandalwood from nearby Timor.[4]:58–61 Influences from the powerful Ternate Sultanate were also believed to be present.[5]

Western presence in the region started with the Portuguese, who captured Malacca in 1511. As they began trading for the sandalwood at Timor, their presence in the region increased. Solor was described by Tomé Pires in his Suma Oriental, although some scholars believe he was referring to nearby larger Flores, mentioning the abundance of exported sulphur and foodstuffs.[4]:61 By 1515, there was trade between both Flores and Solor with the foreigners, and by 1520 a small Portuguese settlement has been constructed in Lifau, at Solor. The trade-in sandalwood also attracted Chinese and Dutch along with nearer Makassarese, creating competition. The Makassarese attacked and captured Larantuka in 1541 to extend their control over the sandalwood trade[3]:81 and in 1613, the Dutch destroyed the Portuguese base at Solor before establishing themselves at modern Kupang.[6]

The first Raja to be baptized was Ola Adobala who was brought up under Portuguese education, traditionally the ninth in the pedigree of the Rajas and baptized during the reign of Peter II of Portugal [2]:174 while present-day traditional celebrations place his baptism at 1650 instead.[7] In addition, Portuguese sources mention a Dom Constantino between 1625-1661, which implies that Adobala may not be the first in the line of Catholic monarchs of Larantuka. Other monarch names mentioned are Dom Luis (1675) and Dom Domingos Viera (1702)[2]:175 The Dominican Order was vital in the spread of Catholicism in the area until their later replacement in the 19th century.[4]:66

The polity maintained some form of a closed-port policy for outsiders in the late 17th century.[4]:60 There were also some interactions with nearby Islam Bima Sultanate, whose Sultan enforced his suzerainty over parts of Western Flores in 1685.[2]:177 Territories of the kingdom were not contiguous and was interspersed by the holdings of several lesser polities, some of which were Muslim.[1]

By 1851, debts incurred by the Portuguese colony in East Timor motivated the Portuguese authorities to "sell" territories covered by Larantuka to the Dutch East Indies, and the transfer was made by 1859 ceding the Portuguese claim/suzerainty over parts of Flores and the island range stretching from Alor to Solor for 200,000 florins and some Dutch holdings in Timor.[8]:54–55 The treaty also confirmed that the Catholic inhabitants of the region will remain so under the authority of Protestant Netherlands, and the Dutch authorities sent Jesuit priests to the area.[9]

On 14 September 1887, a new Raja Don Lorenzo Diaz Vieria Godinho ascended to the throne as Lorenzo II, who was educated by Jesuit priests. Showing clear traits of independence, he attempted to extract taxes from territories belonging to a nearby Raja of Sikka, led groups of men to intervene in local conflicts, and refused to conduct sacrifices in the manner his predecessors did for the non-Catholic natives. Eventually, colonial authorities responded by deposing and exiling him to Java in 1904, where he died six years later.[1]

The royal family remained post-Indonesian independence as traditional figureheads with no legal authority until their final abolishment on 1962.[2]

Legacy

In present-day Indonesia, unique Catholic traditions close to Easter days remain, locally known as the Semana Santa. It involves a procession carrying statues of Jesus and Virgin Mary (locally referred to as Tuan Ana and Tuan Ma) to a local beach, then to Cathedral of the Queen of the Rosary, the seat of the bishop. The raja title is still held by descendants of the past kings (most recently by Don Andre III Marthinus DVG on 2016), although it is not associated with any secular authority.[10][11] The residence (istana) of the king still stands to this day.

According to the 2010 census, the majority of the population in the kingdom's former territories, and the East Nusa Tenggara province as a whole, remained Catholics.[12]

See also

- Portuguese colonialism in Indonesia

- History of Christianity in Indonesia

References

- Barnes, R. H. (Spring 2008). "Raja Lorenzo II: A Catholic Kingdom in the Dutch East Indies" (PDF). IIAS Newsletter. 47. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- Hägerdal, Hans (2012). Lords of the land, lords of the sea : conflict and adaptation in early colonial Timor, 1600-1800. BRILL. ISBN 9789004253506.

- Andaya, Leonard Y (2015). "Applying the seas perspective to Indonesia". Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1350-1800. Routledge. ISBN 9781317559191.

- Abdurachman, Paramita R. (2008). Bunga Angin Portugis di Nusantara : jejak-jejak kebudayaan Portugis di Indonesia. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia. ISBN 9789797992354.

- "Lamalerap: A whaling village in eastern Indonesia". Indonesia. 17: 136–159. April 1974. JSTOR 3350777.

- I Gede Parimatha (2008). Linking Destinies Trade, Towns and Kin in Asian History. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 71–73. ISBN 9789004253995.

- Oktora, Samuel; Ama, Kornelis Kewa (3 April 2010). "Lima Abad Semana Santa Larantuka" (in Indonesian). Kompas. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- Kammen, Douglas (2015). Three Centuries of Conflict in East Timor. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813574127.

- Barnes, R.H. (1 January 2009). "A temple, a mission, and a war: Jesuit missionaries and local culture in East Flores in the nineteenth century". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 165 (1): 32–61. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003642.

- Hidayat, Fikria (27 March 2016). "Semana Santa di Larantuka, Ritual Pekan Suci Paskah Berusia 5 Abad" (in Indonesian). Kompas. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- FS, Miftakhul (16 April 2017). "Cerita Ketika Warga Larantuka Merayakan Ritual Semana Santa" (in Indonesian). Jawa Pos. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- "Penduduk Menurut Wilayah dan Agama yang Dianut Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Timur". Sensus Penduduk 2010 (in Indonesian). Statistics Indonesia. Retrieved 19 August 2017.