Khoda Afarin County

Khoda Afarin County (Persian: شهرستان خداآفرین) is a county in East Azerbaijan Province in Iran. The capital of the county is Khomarlu. At the 2006 census, the county's population was 34,461, in 7,492 families.[1] The county is subdivided into three districts: the Central District, Minjavan District, and Garamduz District. The county has one city: Khomarlu. Until 2011, The county was a district of Kaleybar county.[2] Before the Islamic Revolution, Khomarlu was merely a village which was distinguished from other villages for housing the headquarters of Royal Gendarmery. The notary office was located in Abbasabad village and operated by a cleric, who also acted as the spiritual authority of the whole district.

Khoda Afarin County شهرستان خداآفرین | |

|---|---|

| |

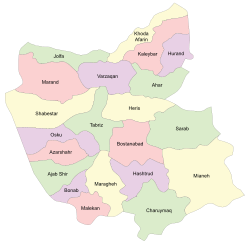

Location in East Azerbaijan Province | |

Location of East Azerbaijan Province in Iran | |

| Country | |

| Province | East Azerbaijan |

| Capital | Khomarlu |

| Bakhsh (Districts) | Central District, Minjavan District, Garamduz District |

| Population (2006) | |

| • Total | 34,461 |

| Time zone | UTC+3:30 (IRST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+4:30 (IRDT) |

Economy

Before the Islamic Revolution of 1978, then a district of Ahar County, had a dynamic economy; the surplus agricultural products from fertile farmlands along Aras were exported to Ahar, and on the lush uplands large herds of sheep was a common sight. Of course, since the turbulent days of Azerbaijan Democratic Government, some residents were travelling to Tehran or Tabriz for seasonal work on construction projects, and by the late 1970s some of these migrant workers were established contractors. Accordingly, majority of active male population was spending half of the year in cities. The Islamic Revolution drastically changed social order. In the 1978–1979 period many of the migrant workers in Tehran constructed illegal dwellings on government lands at the North-East of Tehran and moved their families to the city. During the second big migration wave of the 1990s, most villages of the county were evacuated and residents settled in the shanty-towns at the South-West of Tehran. In recent years, some expatriates have returned and constructed decent houses. The county is already experiencing a construction boom. This has rapidly increased demand for construction workers. Moreover, the capital inflow to the county in anticipation of potential boom in Eco-tourism has resulted in launching many projects related to hotels and campgrounds.

Language

The spoken language of a vast majority of the inhabitants is modern Azeri, which has much similarity to Turkmeni, Afshar and the Anatolian Turkish [3]

The ancient Indo-European, Iranic language of the province before its turkification, survives in the Tati language, particularly in its Karingani dialect. In addition to the large village of Karingan, the villages of Chay Kandi, Kalasor, Khoynarood, and Arazin also are the last speakers of the old native language of Azerbaijan. .[4][5]

The mountainous terrain, shepherding and cultivation of hillsides possess the isolating features for the development of a sophisticated whistled language.[6] The inhabitants of the region employ the fingered whistle format for long range communication. More importantly, the majority of males are able, and perhaps addicted, to masterfully mimic the melodic sounds of musical instruments using fingerless whistle. Melodic whistling, indeed, appears to be a private version of the Ashug music for personal satisfaction.

Historical sites

- Vinaq. An old mansion in Vinaq village, which was built by Tomanies in 1907. The mansion is similar to the Aynaloo mansion in architecture.

- Baba Seyfaddin pilgrimage site near Garmanab village. The village is also a significantly important place as in last 150 years it has been inhabited by Armenians, followers of Yarsan religion and Shia Islam, respectively. The graveyard of Armenians has been preserved and the writings on the grave stones may provide important clues to the history of Arasbaran.[7]

- Khoda Afarin bridges. Two bridges on Aras river are located near Khomarlu. One bridge is badly damaged and the other is still usable for pedestrians. The later bridge is 160 m in length.

- Alherd village. This historical village has an ancient graveyard with tombstones, unusually, engraved with ornamental figures. It is possible that archaeological studies may unravel significant historical evidences.

Khoda Afarin county, and Ashugh music

The county has been known as the epicenter of Arasbaran school of Ashugh music. The mountainous terrain, and the socio-cultural upheavals of the past two centuries have given a characteristic melancholic feature to the songs composed by the rebel-poets originating from the region. A revealing example is a song which was composed by Bahman Zamani following the tragic drowning of Samad Behrangi in Aras.

If, the mighty mountains can boast their height again,

If the crystal-clear water can irrigate the slopes again,

If, again, the ripen fruits can bent green branches,

Then, who says that my melodic words will not outlive me?

Two living masters of Ashugh music, Changiz Mehdipour and Rasool Qorbani, were born in Khoda Afarin county. In addition, many inhabitants, particularly the second generation immigrants living in Tehran, play Kopuz as a manifestation of their long denied cultural identity.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khoda Afarin county. |

- "Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1385 (2006)". Islamic Republic of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 2011-11-11.

- http://www.dolat.ir/NSite/FullStory/News/?Serv=0&Id=196474

- Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, 2010, Elsevier, p. 110-113

- James Stuart Olson, Lee Brigance Pappas, Nicholas Charles Pappas (Editors), An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires 1994, p. 623

- E. Yarshater, Iranian Languages and Texts from Iran and Turan, edited by Maria Macuch, Mauro Maggi, Werner Sundermann, 2007, page 443.

- J.Meyer, Bioacoustics of human whistled languages: an alternative approach to the cognitive processes of language, Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências,76, 405-412, (2004)

- https://www.panoramio.com/photo/95810420