Khanty language

Khanty (or Hanti), previously known as Ostyak (/ˈɒstiæk/),[3] is the Uralic language spoken by the Khanty people. It is spoken in Khanty–Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets autonomous okrugs as well as in Aleksandrovsky and Kargosoksky districts of Tomsk Oblast in Russia. According to the 1994 Salminen and Janhunen study, there were 12,000 Khanty-speaking people in Russia.

| Khanty | |

|---|---|

| ханты ясаӈ hantĭ jasaŋ | |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | Khanty–Mansi |

| Ethnicity | 30,900 Khanty people (2010 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 9,600 (2010 census)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | kca |

| Glottolog | khan1279[2] |

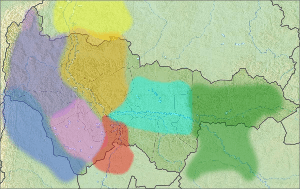

The Khanty language has many dialects. The western group includes the Obdorian, Ob, and Irtysh dialects. The eastern group includes the Surgut and Vakh-Vasyugan dialects, which, in turn, are subdivided into thirteen other dialects. All these dialects differ significantly from each other by phonetic, morphological, and lexical features to the extent that the three main "dialects" (northern, southern and eastern) are mutually unintelligible.[4] Thus, based on their significant multifactorial differences, Eastern, Northern and Southern Khanty could be considered separate but closely related languages.

Alphabet

Cyrillic (version as of 2000)

| А а | Ӓ ӓ | Ӑ ӑ | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е |

| Ё ё | Ә ә | Ӛ ӛ | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Қ қ (Ӄ ӄ) | Л л | Ԯ ԯ (Ԓ ԓ) | М м | Н н | Ң ң (Ӈ ӈ) | Н’ н’ | О о |

| Ӧ ӧ (О̆ о̆) | Ө ө | Ӫ ӫ (Ө̆ ө̆) | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ӱ ӱ | Ў ў | Ф ф | Х х | Ҳ ҳ (Ӽ ӽ) | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ҷ ҷ |

| Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Є є | Є̈ є̈ |

| Ю ю | Ю̆ ю̆ | Я я | Я̆ я̆ |

Cyrillic (version as of 1958)

| А а | Ӓ ӓ | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё |

| Ә ә | Ӛ ӛ | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к | Ӄ ӄ |

| Л л | Л’ л’ | М м | Н н | Ӈ ӈ | О о | Ӧ ӧ | Ө ө |

| Ӫ ӫ | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ӱ ӱ | Ф ф |

| Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ч’ ч’ | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы |

| Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Latin (1931–1937)

| A a | B в | D d | E e | Ә ә | F f | H h | Һ һ |

| I i | J j | K k | L l | Ļ ļ | Ł ł | M m | N n |

| Ņ ņ | Ŋ ŋ | O o | P p | R r | S s | Ş ş | Ꞩ ꞩ |

| T t | U u | V v | Z z | Ƶ ƶ | Ƅ ƅ |

Literary language

.svg.png)

The Khanty written language was first created after the October Revolution on the basis of the Latin script in 1930 and then with the Cyrillic alphabet (with the additional letter ⟨ң⟩ for /ŋ/) from 1937.

Khanty literary works are usually written in three Northern dialects, Kazym, Shuryshkar, and Middle Ob. Newspaper reporting and broadcasting are usually done in the Kazymian dialect.

Varieties

Khanty is divided in three main dialect groups, which are to a large degree mutually unintelligible, and therefore best considered three languages: Northern, Southern and Eastern. Individual dialects are named after the rivers they are or were spoken on. Southern Khanty is probably extinct by now.[5][6]

- Eastern Khanty[7]

- Far Eastern (Vakh, Vasjugan, Verkhne-Kalimsk, Vartovskoe)

- Surgut (Jugan, Malij Jugan, Pim, Likrisovskoe, Tremjugan, Tromagan)

- transitional: Salym

- Western Khanty

The Salym dialect can be classified as transitional between Eastern and Southern (Honti:1998 suggests closer affinity with Eastern, Abondolo:1998 in the same work with Southern). The Atlym and Nizyam dialects also show some Southern features.

Southern and Northern Khanty share various innovations and can be grouped together as Western Khanty. These include loss of full front rounded vowels: *üü, *öö, *ɔ̈ɔ̈ > *ii, *ee, *ää (but *ɔ̈ɔ̈ > *oo adjacent to *k, *ŋ),[8] loss of vowel harmony, fricativization of *k to /x/ adjacent to back vowels,[9] and the loss of the *ɣ phoneme.[10]

Phonology

A general feature of all Khanty varieties is that while long vowels are not distinguished, a contrast between plain vowels (e.g. /o/) vs. reduced or extra-short vowels (e.g. /ŏ/) is found. This corresponds to an actual length distinction in Khanty's close relative Mansi. According to scholars who posit a common Ob-Ugric ancestry for the two, this was also the original Proto-Ob-Ugric situation.

Palatalization of consonants is phonemic in Khanty, as in most other Uralic languages. Retroflex consonants are also found in most varieties of Khanty.

Khanty word stress is usually on the initial syllable.[11]

Proto-Khanty

| Bilabial | Dental | Palatal(ized) | Retroflex | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | *m [m] | *n [n] | *ń [nʲ] | *ṇ [ɳ] | *ŋ [ŋ] | |

| Plosive | *p [p] | *t [t] | *k [k] | |||

| Affricate | *ć [tsʲ] | *č̣ [ʈʂ] | ||||

| Fricative | central | *s [s] | *γ [ɣ] | |||

| lateral | *ᴧ [ɬ] | |||||

| Lateral approximant | *l [l] | *ľ [lʲ] | *ḷ [ɭ] | |||

| Trill | *r [r] | |||||

| Semivowel | *w [w] | *j [j] | ||||

19 consonants are reconstructed for Proto-Khanty, listed with the traditional UPA transcription shown above and an IPA transcription shown below.

A major consonant isogloss among the Khanty varieties is the reflexation of the lateral consonants, *ɬ (from Proto-Uralic *s and *š) and *l (from Proto-Uralic *l and *ð).[10] These generally merge, however with varying results: /l/ in the Obdorsk and Far Eastern dialects, /ɬ/ in the Kazym and Surgut dialects, and /t/ elsewhere. The Vasjugan dialect still retains the distinction word-initially, having instead shifted *ɬ > /j/ in this position. Similarly, the palatalized lateral *ľ developed to /lʲ/ in Far Eastern and Obdorsk, /ɬʲ/ in Kazym and Surgut, and /tʲ/ elsewhere. The retroflex lateral *ḷ remains in Far Eastern, but in /t/-dialects develops into a new plain /l/.

Other dialect isoglosses include the development of original *ć to a palatalized stop /tʲ/ in Eastern and Southern Khanty, but to a palatalized sibilant /sʲ ~ ɕ/ in Northern, and the development of original *č similarly to a sibilant /ʂ/ (= UPA: š) in Northern Khanty, partly also in Southern Khanty.

Eastern Khanty

Far Eastern

The Vakh dialect is divergent. It has rigid vowel harmony and a tripartite (ergative–accusative) case system: The subject of a transitive verb takes the instrumental case suffix -nə-, while the object takes the accusative case suffix. The subject of an intransitive verb, however, is not marked for case and might be said to be absolutive. The transitive verb agrees with the subject, as in nominative–accusative systems.

Vakh has the richest vowel inventory, with four reduced vowels /ĕ ø̆ ɑ̆ ŏ/ and full /i y ɯ u e ø o æ ɑ/. Some researchers also report /œ ɔ/.[12]

| Bilabial | Dental | Palatal/ized | Retroflex | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | n | nʲ | ɳ | ŋ |

| Stops | p | t | tʲ | k | |

| Affricate | ʈʂ | ||||

| Fricatives | s | ɣ | |||

| Lateral approximants | l | lʲ | ɭ | ||

| Trill | r | ||||

| Semivowels | w | j |

Surgut

| Bilabial | Dental / Alveolar | Palatal/ized | Post- alveolar | Velar | Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n̪ | nʲ | ŋ | |||

| Stop / Affricate | p | t̪ | tʲ ~ tɕ 1 | tʃ | k 2 | q 2 | |

| Fricative | central | s | (ʃ) 3 | ʁ | |||

| lateral | ɬ 4 | ɬʲ | |||||

| Approximant | central | w | j | (ʁ̞ʷ) 5 | |||

| lateral | l | ||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

Notes:

- /tʲ/ can be realized as an affricate [tɕ] in the Tremjugan and Agan sub-dialects.

- The velar/uvular contrast is predictable in inherited vocabulary: [q] appears before back vowels, [k] before front and central vowels. However, in loanwords from Russian, [k] may also be found before back vowels.

- The phonemic status of [ʃ] is not clear. It occurs in some words in variation with [s], in others in variation with [tʃ].

- In the Pim sub-dialect, /ɬ/ has recently shifted to /t/, a change that has spread from Southern Khanty.

- The labialized postvelar approximant [ʁ̞ʷ] occurs in the Tremjugan sub-dialect as an allophone of /w/ between back vowels, for some speakers also word-initially before back vowels. Research from the early 20th century also reported two other labialized phonemes: /kʷ~qʷ/ and /ŋʷ/, but these are no longer distinguished.

Northern Khanty

The Kazym dialect distinguishes 18 consonants.

| Bilabial | Dental | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | pal. | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ | ɳ | ŋ | ||

| Plosive | p | t | k | ||||

| Fricative | central | s | sʲ | ʂ | x | ||

| lateral | ɬ | ɬʲ | |||||

| Approximant | central | w | j | ||||

| lateral | ɭ | ||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

The vowel inventory is much simplified. Eight vowels are distinguished in initial syllables: four full /e a ɒ o/ and four reduced /ĭ ă ŏ ŭ/. In unstressed syllables, four values are found: /ɑ ə ĕ ĭ/.[14]

A similarly simple vowel inventory is found in the Nizyam, Sherkal, and Berjozov dialects, which have full /e a ɒ u/ and reduced /ĭ ɑ̆ ŏ ŭ/. Aside from the full vs. reduced contrast rather than one of length, this is identical to that of the adjacent Sosva dialect of Mansi.[12]

The Obdorsk dialect has retained full close vowels and has a nine-vowel system: full vowels /i e æ ɑ o u/ and reduced vowels /æ̆ ɑ̆ ŏ/).[12] It however has a simpler consonant inventory, having the lateral approximants /l lʲ/ in place of the fricatives /ɬ ɬʲ/ and having fronted *š *ṇ to /s n/.

Grammar

The noun

The nominal suffixes include dual -ŋən, plural -(ə)t, dative -a, locative/instrumental -nə.

For example:

- xot "house" (cf. Finnish koti "home")

- xotŋəna "to the two houses"

- xotətnə "at the houses" (cf. Hungarian otthon, Finnish kotona "at home", an exceptional form using the old, locative meaning of the essive case ending -na).

Singular, dual, and plural possessive suffixes may be added to singular, dual, and plural nouns, in three persons, for 33 = 27 forms. A few, from məs "cow", are:

- məsem "my cow"

- məsemən "my 2 cows"

- məsew "my cows"

- məstatən "the 2 of our cows"

- məsŋətuw "our 2 cows"

Pronouns

The personal pronouns are, in the nominative case:

| SG | DU | PL | |

| 1st person | ma | min | muŋ |

| 2nd person | naŋ | nən | naŋ |

| 3rd person | tuw | tən | təw |

The cases of ma are accusative manət and dative manəm.

The demonstrative pronouns and adjectives are:

- tamə "this", tomə "that", sit "that yonder": tam xot "this house".

Basic interrogative pronouns are:

- xoy "who?", muy "what?"

Numerals

Khanty numerals, compared with Hungarian and Finnish, are:

| # | Khanty | Hungarian | Finnish |

| 1 | yit, yiy | egy | yksi |

| 2 | katn, kat | kettő, két | kaksi |

| 3 | xutəm | három | kolme |

| 4 | nyatə | négy | neljä |

| 5 | wet | öt | viisi |

| 6 | xut | hat | kuusi |

| 7 | tapət | hét | seitsemän |

| 8 | nəvət | nyolc | kahdeksan |

| 9 | yaryaŋ (short of ten?) | kilenc | yhdeksän |

| 10 | yaŋ | tíz | kymmenen |

| 20 | xus | húsz | kaksikymmentä |

| 30 | xutəmyaŋ (3 tens) | harminc | kolmekymmentä |

| 40 | nyatəyaŋ (4 tens) | negyven | neljäkymmentä |

| 100 | sot | száz | sata |

The formation of multiples of ten shows Slavic influence in Khanty, whereas Hungarian uses the collective derivative suffix -van (-ven) closely related to the suffix of the adverbial participle which is -va (-ve) today but used to be -ván (-vén). Note also the regularity of [xot]-[haːz] "house" and [sot]-[saːz] "hundred".

Syntax

Both Khanty and Mansi are basically nominative–accusative languages but have innovative morphological ergativity. In an ergative construction, the object is given the same case as the subject of an intransitive verb, and the locative is used for the agent of the transitive verb (as an instrumental) . This may be used with some specific verbs, for example "to give": the literal Anglicisation would be "by me (subject) a fish (object) gave to you (indirect object)" for the equivalent of the sentence "I gave a fish to you". However, the ergative is a morphological (marked using a case) only, not syntactic, so that, in addition, these may be passivized in a way resembling English. For example, in Mansi, "a dog (agent) bit you (object)" could be reformatted as "you (object) were bitten, by a dog (instrument)".

Khanty is an agglutinative language and employs an SOV order.[15]

Lexicon

The lexicon of the Khanty varieties is documented relatively well. The most extensive early source is Toivonen (1948), based on field records by K. F. Karjalainen from 1898–1901. An etymological interdialectal dictionary, covering all known material from pre-1940 sources, is Steinitz et al. (1966–1993).

Schiefer (1972)[16] summarizes the etymological sources of Khanty vocabulary, as per Steinitz et al., as follows:

| Inherited | 30% | Uralic | 5% |

| Finno-Ugric | 9% | ||

| Ugric | 3% | ||

| Ob-Ugric | 13% | ||

| Borrowed | 28% | Komi | 7% |

| Samoyedic (Selkup and Nenets) | 3% | ||

| Tatar | 10% | ||

| Russian | 8% | ||

| unknown | 40% |

Futaky (1975)[17] additionally proposes a number of loanwords from the Tungusic languages, mainly Evenki.

Notes

- Khanty at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Khantyic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh

- Gulya 1966, pp. 5-6.

- Abondolo 1998, pp. 358-359.

- Honti 1998, pp. 328-329.

- Honti, László (1981), "Ostjakin kielen itämurteiden luokittelu", Congressus Quintus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum, Turku 20.-27. VIII. 1980, Turku: Suomen kielen seura, pp. 95–100

- Honti 1998, p. 336.

- Abondolo 1998, pp. 358–359.

- Honti 1998, p. 338.

- Estill, Dennis (2004). Diachronic change in Erzya word stress. Helsinki: Finno-Ugrian Society. p. 179. ISBN 952-5150-80-1.

- Abondolo 1998, p. 360.

- Csepregi 2011, pp. 12-13.

- Honti 1998, p. 337.

- Grenoble, Lenore A (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Springer. p. 14. ISBN 9781402012983.

- Schiefer, Erhard (1972). "Wolfgang Steinitz. Dialektologisches und etymologisches Wörterbuch der ostjakischen Sprache. Lieferung 1 – 5, Berlin 1966, 1967, 1968, 1970, 1972". Études Finno-Ougriennes. 9: 161–171.

- Futaky, István (1975). Tungusische Lehnwörter des Ostjakischen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

References

- Abondolo, Daniel (1998). "Khanty". In Abondolo, Daniel (ed.). The Uralic Languages.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Csepregi, Márta (1998). Szurguti osztják chrestomathia (pdf). Studia Uralo-Altaica Supplementum. 6. Szeged. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- Filchenko, Andrey Yury (2007). A grammar of Eastern Khanty (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). Rice University. hdl:1911/20605.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gulya, János (1966). Eastern Ostyak chrestomathy. Indiana University Publications, Uralic and Altaic series. 51.

- Honti, László (1988). "Die Ob-Ugrischen Sprachen". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Uralic Languages.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Honti, László (1998). "ObUgrian". In Abondolo, Daniel (ed.). The Uralic Languages.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steinitz, Wolfgang, ed. (1966–1993). Dialektologisches und etymologisches Wörterbuch der ostjakischen Sprache. Berlin. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Toivonen, Y. H., ed. (1948). K. F. Karjalainen's Ostjakisches Wörterbuch. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

External links

| Khanty language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |