Khan Dannun

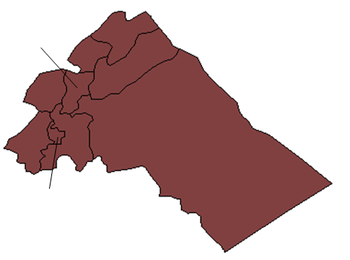

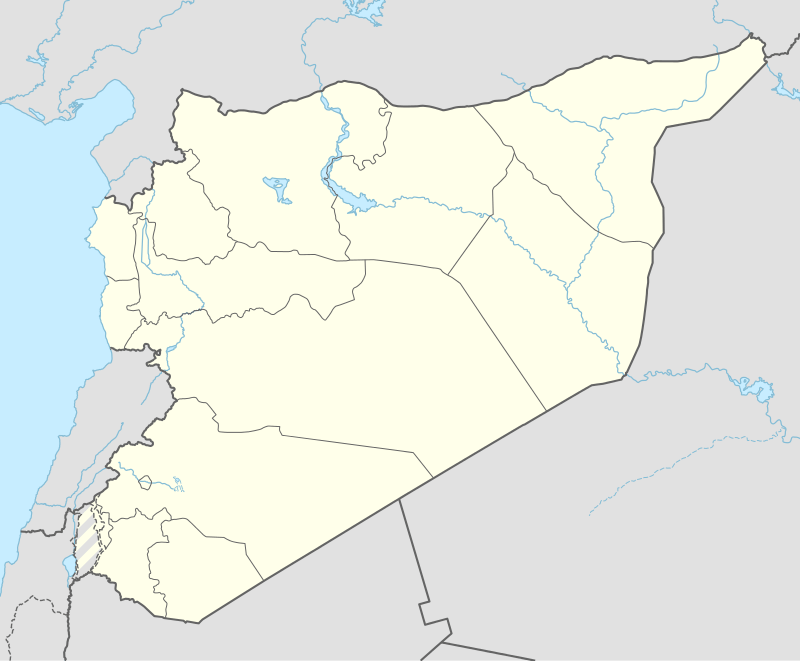

Khan Dannun (Arabic: خان دنون, also spelled Khan Danun, Khan Dunnun or Khan Dhul-Nun) is a town in southern Syria, administratively part of the Markaz Rif Dimashq District of the Rif Dimashq Governorate. Located south of Damascus, nearby localities include al-Taybah to the west, Muqaylibah to the northwest, al-Kiswah 5 kilometers to the north and Khiyarat Dannun to the east. According to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics, Khan Dannun had a population of 8,727 in the 2004 census.[1]

Khan Dannun خان دنون Khan Danoun | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Khan Dannun | |

| Coordinates: 33°19′55″N 36°19′56″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Rif Dimashq Governorate |

| District | Markaz Rif Dimashq |

| Nahiya | Al-Kiswah |

| Population (2004) | |

| • Total | 8,727 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (EEST) |

Khan Dannun also contains a refugee camp with the same name and is one of ten Palestinian refugee camps in Syria recognized by UNRWA. According to UNRWA statistics the camp had a population of 7,841 in 1998.[2] According to UNRWA the population of the camp in June 2008 was 9,479 persons and 2,192 families.[3]

History

Khan Dannun was originally a large khan ("caravansary") completed in 1376 by the Mamluk governor of Damascus, Manjak al-Yusufi,[4] during the reign of the Bahri Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Sha'ban.[5] The khan was designed by Ali ibn al-Badri, known as muhandis ash-Sham ("engineer of Damascus.")[6] The name "Dan nun" is the colloquial version of "Dhul-Nun,"[7][8] a highly venerated 9th-century Muslim figure. He is considered to be the early patriarch of the Sufis.[7] Khan Dannun became a stopping point on the hajj ("pilgrimage to Mecca") caravan route after al-Kiswah, and before Ghabaghib.[9]

The khan, with exception of its vaults, was built in the traditional basalt masonry typically found in the old structures in Hauran.[4] It consisted of an open, square-shaped courtyard, the center of which had been occupied by livestock. Surrounding the courtyard were arcades built atop lodging apartments which served as accommodation for visitors.[10] The courtyard was flanked by circular basalt towers.[7] Inside the khan was a small prayer room with mihrab niche which indicated the direction of Mecca.[11] A marsh was formed in front of the khan's gate as a result of an eastern-flowing rivulet.[7]

When traveler John Lewis Burckhardt visited the site in the early 19th-century, the khan was in ruins.[10] Khan Dannun was one of the stops on the Damascus-Hauran line of the Hejaz Railway.[12]

In 1949, following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, a Palestinian refugee camp called Khan Dannun was set up in the town.[13] In 2009 a new sewage project for Khan Dannun, funded by the European Commission, was finished.[14]

References

- General Census of Population and Housing 2004. Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Rif Dimashq Governorate. (in Arabic)

- Mahmoud as-Sahly, Nabil. Profiles: Palestinian Refugees in Syria Archived 2014-08-11 at the Wayback Machine. BADIL. Winter 1999.

- Total Registered Camp Population-Summary. UNRWA. 2008-06-30.

- Meinecke, 1996, p. 46

- Bosworth, 1989, p. 548

- Meinecke, 1996, p. 53

- Newbold, 1846, p. 334

- Ed. Popper, 1955, p. 51. Translated work of Ibn Taghribirdi.

- Museums With No Frontiers, 2000, p. 202

- Burckhardt, 1822, p. 54

- Constable, 2004, p. 99

- Masterman, 1897, p. 200

- Khan Danoun Refugee Camp. Jerusalem Media and Communications Center (JMCC). 2007-01-01.

- UNRWA Commissioner-General Visits Syria. UNRWA. 2009-04-23.

Bibliography

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1989). Encyclopaedia of Islam , Fascicle 107, Parts 107-108. Brill Archive. ISBN 9004090827.

- Burckhardt, Johann Ludwig (1822). Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. J. Murray.

- Constable, Olivia Remia (2004). Housing the Stranger in the Mediterranean World: Lodging, Trade, and Travel in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521819180.

- Masterman, E. W. G. (1897). "The Damascus Railways". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 29: 198–200.

- Meinecke, Michael (1996). Patterns of Stylistic Changes in Islamic Architecture: Local Traditions Versus Migrating Artists. New York University Press. ISBN 9780814754924.

- Museum With No Frontiers (2000). The Umayyads: The Rise of Islamic Art. AIRP. ISBN 187404435X.

- Newbold, Captain (1846). "On the site of Ashtaroth". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society: JRGS. Murray. 16: 331–338.

- Ibn Taghribirdi (1955). William Popper (ed.). University of California publications in Semitic philology. 15-17. The University of California Press.