Kappa (folklore)

A kappa (河童, river-child)—also known as kawatarō (川太郎, "river-boy"), komahiki (駒引, horse-puller), kawatora (川虎, river-tiger) or suiko (水虎, water-tiger)–is an amphibious yōkai demon or imp found in traditional Japanese folklore. They are typically depicted as green, human-like beings with webbed hands and feet and a turtle-like carapace on their backs. A depression on its head, called its "dish" (sara), retains water, and if this is damaged or its liquid is lost (either through spilling or drying up), the kappa is severely weakened.

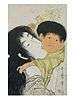

A drawing of a kappa. —From an 1836 copy of Koga Tōan's Suiko Kōryaku (1820). | |

| Grouping | Yōkai |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) | Gatarō, Kawako |

| Country | Japan |

The kappa are known to favor cucumbers and love to engage in sumo wrestling. They are often accused of assaulting humans in water and removing a mythical organ called the shirikodama from their victim's anus.

Terminology

The name kappa is a portmanteau of the words kawa (river) and wappa, a variant form of 童 warawa (also warabe) "child". Another translation of kappa is "water sprites".[1] The kappa are also known regionally by at least eighty other names such as kawappa, kawako, kawatarō, gawappa, kōgo, mizushi, mizuchi, suitengu.[2]

Its names kawaso meaning "otter", dangame "soft-shelled turtle", and enkō "monkey" suggest its outward resemblance to these animals. The name komahiki or "steed-puller" alludes to its reputed penchant to drag away horses.[2]

The kappa has been known as kawako in Izumo (Shimane Prefecture) where Lafcadio Hearn was based,[3] and gatarō was the familiar name of it to folklorist Kunio Yanagita from Hyogo Prefecture.[4]

Appearance

The kappa is said to be roughly humanoid in form and about the size of a child, inhabiting the ponds and rivers of Japan.[5] Clumsy on land, they are at home in the water, and thrive during the warm months.[6] It is typically greenish in color[7] (or yellow-blue[8]), and either scaly[9][10] or slimy skinned, with webbed hands and feet, and a turtle-like carapace on its back.[7] Inhuman traits include three anuses that allow them to pass three times as much gas as humans.[6] Kappa are generally the size and shape of a human child, yet despite their small stature they are physically stronger than a grown man.[6]

One peculiar trait is that it has a cavity on its head called a sara ("dish", "bowl", or "plate") that retains water or some sort of liquid, which is regarded as the source of the kappa's power or life force. This cavity must be full whenever a kappa is away from the water; if it ever dries out, or if its water is spilled, kappa loses its power and may even die.[11][12][10] The kappa are sometimes said to smell like fish,[8] and they can swim like them.

According to some accounts, its arms are connected to each other through the torso and can slide from one side to the other.[13] While they are primarily water creatures, they do on occasion venture onto land. When they do, the "dish" on their head can be covered with a metal cap for protection.[14]

A hairy kappa is called a hyōsube.[15]

A book illustrating twelve kinds of kappa.

A book illustrating twelve kinds of kappa. A kappa by Katsushika Hokusai

A kappa by Katsushika Hokusai_Utamakura_print_No._01_(BM%2C_cropped).jpg)

Behavior

Kappa are usually seen as mischievous troublemakers or trickster figures. Their actions range from the comparatively minor, such as looking up women's kimonos, to the outright malevolent, such as drowning people and animals, kidnapping children, raping women and at times eating human flesh.[14] Though sometimes menacing, it may also behave amicably towards humans.[9] While younger kappa are frequently found in family groups, adult kappa live solitary lives. However, it is common for kappa to befriend other yōkai and sometimes even people.[16]

Cucumber

Folk beliefs claim the cucumber as their traditional favorite meal.[14] At festivals, offerings of cucumber are frequently made to the kappa.[17] Sometimes the kappa is said to have other favorite foods, such as the Japanese eggplant, soba (buckwheat noodles), nattō (fermented soybeans), or kabocha.[18]

In Edo (old Tokyo), there used to be a tradition where people would write the names of their family members on cucumbers and send them afloat into the streams to mollify the kappa, to prevent the family from coming to harm in the streams.[19] In some regions, it was customary to eat cucumbers before swimming as protection, but in others it was believed that this act would guarantee an attack.[17]

As a menace

As water monsters, kappa have been blamed for drownings, and are often said to try to lure people into water and pull them in with their great skill at wrestling.[14] They are sometimes said to take their victims for the purpose of drinking their blood, eating their livers, or gaining power by taking their shirikodama (尻子玉), a mythical ball said to contain the soul, which is located inside the anus.[14][20][21]

Kappa have been used to warn children of the dangers lurking in rivers and lakes, as kappa have been often said to try to lure people to water and pull them in.[22][14] Even today, signs warning about kappa appear by bodies of water in some Japanese towns and villages.

Kappa are also said to victimize animals, especially horses and cows. The motif of the kappa trying to drown a horse is found all over Japan.[23]

Lafcadio Hearn wrote of a story in Kawachimura near Matsue where a horse-stealing kappa was captured and made to write a sworn statement vowing never to harm people again.[3][12]

In many versions the kappa is dragged by the horse to the stable where it is most vulnerable, and it is there it is forced to submit a writ of promise not to misbehave.[24]

Defeating the kappa

It was believed that there were a few means of escape if one was confronted with a kappa. Kappa are obsessed with politeness, so if a person makes a deep bow, it will return the gesture. This results in the kappa spilling the water held in the "dish" (sara) on its head, rendering it unable to leave the bowing position until the plate is refilled with water from the river in which it lives. If a person refills it, the kappa will serve that person for all eternity.[14] A similar weakness of the kappa involves its arms, which can easily be pulled from its body. If an arm is detached, the kappa will perform favors or share knowledge in exchange for its return.[25]

Another method of defeat involves shogi or sumo wrestling: a kappa sometimes challenges a human being to wrestle or engage in other tests of skill.[26] This tendency is easily used to encourage the kappa to spill the water from its sara. One notable example of this method is the folktale of a farmer who promises his daughter's hand in marriage to a kappa in return for the creature irrigating his land. The farmer's daughter challenges the kappa to submerge several gourds in water. When the kappa fails in its task, it retreats, saving the farmer's daughter from the marriage.[17] Kappa have also been driven away by their aversion to iron, sesame, or ginger.[27]

Good deeds

Kappa are not entirely antagonistic to human beings.

Once befriended, kappa may perform any number of tasks for human beings, such as helping farmers irrigate their land. Sometimes, they bring fresh fish, which is regarded as a mark of good fortune for the family that receives it.[25] They are also highly knowledgeable about medicine, and legend states that they taught the art of bone setting to human beings.[14][28][29]

Localizations

Along with the oni and the tengu, the kappa is among the best-known yōkai in Japan.[30][31]

The kappa is known by various names of the creature vary by region and local folklore.[2] In Shintō, they are often considered to be an avatar (keshin) of the Water Deity or suijin.[32]

Shrines are dedicated to the worship of kappa as water deity in such places as Aomori Prefecture[9] or Miyagi Prefecture.[33] There were also festivals meant to placate the kappa in order to obtain a good harvest, some of which still take place today. These festivals generally took place during the two equinoxes of the year, when the kappa are said to travel from the rivers to the mountains and vice versa.[34]

The best known place where it has been claimed Kappa reside is in the Kappabuchi waters of Tōno in the Iwate Prefecture. The nearby Jōkenji In Tōno, there is a Buddhist temple that has komainu dog statues with depressions on their heads reminiscent of the water-retaining dish on the kappa's heads, said to be dedicated to the kappa which according to legend helped extinguish a fire at the temple.[35] The Kappa is also venerated at the Sogenji Buddhist temple in the Asakusa district of Tokyo where according to tradition, a mummified arm of a Kappa is enshrined within the chapel hall since 1818.

In his Tōno Monogatari, Kunio Yanagita records a number of beliefs from the Tōno area about women being accosted and even impregnated by kappa.[36] Their offspring were said to be repulsive to behold, and were generally buried.[36]

Cross culture lore

Similar folklore can be found in Asia and Europe. The Japanese folklore creature Kappa is known in Chinese folklore as 水鬼[37] "Shui Gui", Water Ghost, or water monkey and may also be related to the Kelpie of Scotland and the Neck of Scandinavia. Like the Japanese description of the beast, in Chinese and in Scandinavian lore this beast is infamous for kidnapping and drowning people as well as horses. The Siyokoy of the Philippine islands is also known for kidnapping children by the water's edge. A frog-face vodyanoy is known in Russian mythology. A green human-like being named a vodnik is widely known in western Slavic folklore and tales, especially in the Czech Republic or Slovakia.

In media

Kappas, and creatures based on them, are recurring characters in Japanese tokusatsu films and television shows. Examples include the kappas in the Daiei/Kadokawa series Yokai Monsters, Nikkatsu's Death Kappa, and King Kappa, a kaiju from the 1972 Tsuburaya Productions series Ultraman Ace.[38]

In Japan, the character Sagojō (Sha Wujing) is conventionally depicted as a kappa: he being a comrade of the magic monkey Gokū in the Chinese story Journey to the West.[22]

The kappa is probably the best known creature of the Japanese folk imagination; its manifestations cut across genre lines, appearing in folk religion, beliefs, legends, folktales and folk metaphors.[2]

These yokai also represent Japan as a nation, featuring in advertisements for a range of products from a major brand of sake to Tokyo-Mitsubishi Bank’s DC Card (a credit card). In their explicitly commercial conceptions, yokai are no longer frightening or mysterious—the DC Card Kappa, for example, is not a slimy water creature threatening to kill unsuspecting children but a cute and (almost) cuddly cartoon character.[39]

Summer Days with Coo is a 2007 Japanese animated film about a kappa and its impact on an ordinary family, written for the screen and directed by Keiichi Hara based on two novels by Masao Kogure.[40]

Kappas are a recurring image in David Peace's novel Patient X,[41] about the life and work of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa.

It is said that the company president of Calbee liked Kappa, so he wanted the name "Kappa" to be included in one of his products. That brought about Kappa Ebisen, a popular shrimp flavored snack in Japan.[42]

In the live-action Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles III movie, the turtles were viewed as "Kappa" when they traveled back in time to Feudal Japan.

In the video game series Animal Crossing the character Kapp'n is depicted as a Kappa in the Japanese versions of the game.

In the video game SMITE, Kuzenbo, supposed King of the Kappas is a playable God.

In the anime series Sarazanmai, the main characters are turned into Kappas by the Prince of the Kappas and collect shirikodama.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kappa. |

- Kappabashi-dori, a Tokyo street named after the kappa

- Kijimuna, a spirit creature from Okinawa

- Kappa, a novel by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

- Koopa

References

- Shamoon, Deborah (2013). "The Yōkai in the Database: Supernatural Creatures and Folklore in Manga and Anime". Marvels & Tales. 27 (2): 276–289. doi:10.13110/marvelstales.27.2.0276. ISSN 1521-4281. JSTOR 10.13110/marvelstales.27.2.0276.

- Foster (1998), p. 3, citing Ōno (1994), p. 14

- Hearn, Lafcadio (1910). Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan. Tauchnitz. pp. 302–303.

- Irokawa, Daikichi (1988). The Culture of the Meiji Period. Princeton University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-691-00030-5.

- Foster (2015), p. 157.

- "Kappa | Yokai.com". Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- Foster (2015), p. 88.

- Foster (1998), p. 4.

- Frédéric, Louis (2002). "kappa". Japan Encyclopedia. President and Fellows of Harvard College. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-674-00770-3.

- Volker, T. (1975). The Animal in Far Eastern Art and Especially in the Art of the Japanese. p. 110. ISBN 978-90-04-04295-7.

- Foster (1998), p. 4; Foster (2015), p. 88

- Davis, F. Hadland (1912). Myths and Legends of Japan. New York: T.Y. Crowell Co. pp. 350–351.

- According to the Wakan Sansai Zue. Foster (1998), p. 6

- Ashkenazi, Michael (2003). Handbook of Japanese Mythology. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-1-57607-467-1. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース: カッパ, ヒョウスベ [Folktale Data of Strange Phenomena and Yōkai] (in Japanese). International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

- "Kappa | Yokai.com". Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- Foster (1998), p. 5.

- Foster (1998), p. 5, citing Takeda, Akira (1988), "Suijinshinkō to kappa 水神信仰と河童 [Water deity belief and the kappa]"; Ōshima, Takehiko ed. Kappa 河童, p. 12.

- 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース: 河童雑談 [Folktale Data of Strange Phenomena and Yōkai] (in Japanese). International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

- "Shirikodama". tangorin.com.

- Nara, Hiroshi (2007). Inexorable Modernity: Japan's Grappling with Modernity in the Arts. Lexington Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7391-1841-2.

- Does Kappa still have their occult power?. road-station.com (Michi-no-eiki).

- Ishida & Yoshida (1950), pp. 1–2, 114–115

- Foster (1998), p. 8, 10.

- Foster (1998), p. 8.

- Foster, Michael Dylan (2009). Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yōkai. University of California Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-520-25361-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foster (1998), p. 6, citing Ōno (1994), p. 42

- 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース: 河童の教えた中風の薬 [Folktale Data of Strange Phenomena and Yōkai] (in Japanese). International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

- 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース: 河童の秘伝接骨薬 [Folktale Data of Strange Phenomena and Yōkai] (in Japanese). International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

- Kyōgoku, Natsuhiko; Tada, Katsumi (2000). Yōkai zuka (in Japanese). Tōkyō: Kokusho Kankōkai. p. 147. ISBN 978-4-336-04187-6.

- Tada, Katsumi (1990). 幻想世界の住人たち Iv 日本編 幻想世界の住人たち. Truth In Fantasy (in Japanese). IV. 新紀元社. p. 110. ISBN 978-4-915146-44-2.

- Frédéric, Louis (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. President and Fellows of Harvard Colleg e. p. 910. ISBN 978-0-674-00770-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース: 河童神社 [Folktale Data of Strange Phenomena and Yōkai] (in Japanese). International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

- Foster (1998), p. 9.

- Masatoshi, Naitō (内藤正敏) (1994). Tōno monogatari no gen fūkei 遠野物語の原風景 [Original landscape of the Tōno monogatari]. p. 176.

- Tatsumi, Takayuki (1998). "Deep North Gothic: A Comparative Cultural Reading of Kunio Yanagita's Tono Monogatari and Tetsutaro Murano's The Legend of Sayo". Newsletter of the Council for the Literature of the Fantastic. 1 (5). Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- "水鬼_水鬼[传说的角色]_互动百科". www.baike.com. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

- "Ultraman Ace". Beta Capsule Reviews. 2018-01-26. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- Foster, Michael Dylan (2009). Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai (1 ed.). University of California Press. doi:10.1525/j.ctt1ppkrc.11 (inactive 2020-06-04). ISBN 978-0-520-25361-2. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppkrc.

- Summer Days with Coo, retrieved 2020-05-20

- Peace, David (2018). Patient X : the case-book of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-5255-2177-8. OCLC 1013525517.

- "第九十九回「い組」お稽古「江戸の妖怪・化物」アダム・カバット – 和塾" (in Japanese). Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- Bibliography

- Foster, Michael Dylan (2015). The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-95912-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foster, M. D. (1998). "The Metamorphosis of the Kappa: Transformation of Folklore to Folklorism in Japan". Asian Folklore Studies. 57 (1): 1–24. doi:10.2307/1178994. JSTOR 1178994. S2CID 126656337.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) JSTOR 1178994

- Ishida, Eiichirô; Yoshida, Ken'ichi (1950). "The Kappa Legend: A Comparative Ethnological Study on the Japanese Water-Spirit"Kappa" and Its Habit of Trying to Lure Horses into the Water". Folklore Studies. 9: 1–2. JSTOR 1177401.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Mark Schumacher (2004). Kappa – River Imp or Sprite. Retrieved March 23, 2006.

- Garth Haslam (2000). Kappa Quest 2000. Retrieved December 14, 2006.

- Kirainet (2007). For a look at Kappa in popular culture Kirainet. Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- Hyakumonogatari.com Translated kappa stories from Hyakumonogatari.com

- Kappa Unknown Explorers

- Underwater Love (2011)

- The Great Yokai War (2005)

- Summer Days with Coo (2009) Animation film featuring a Kappa as main character.