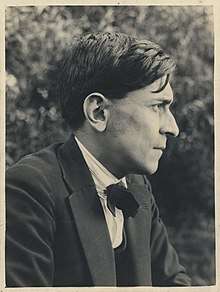

José Carlos Mariátegui

José Carlos Mariátegui La Chira (14 June 1894 – 16 April 1930) was a Peruvian intellectual, journalist and political philosopher. A prolific writer before his early death at the age of 35, he is considered one of the most influential Latin American socialists of the 20th century. Mariátegui's Seven Interpretive Essays on Peruvian Reality (1928) is still widely read in South America, and called "one of the broadest, deepest, and most enduring works of the Latin American century".[1] An avowed self-taught Marxist, he insisted that a socialist revolution should evolve organically in Latin America based on local conditions and practices, not the result of mechanically applying a European formula. Although best known as a political thinker, his literary writings have gained attention by scholars.[2]

José del Carmen Eliseo Mariátegui De La Chira | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 14 June 1894 Moquegua, Peru |

| Died | 16 April 1930 (aged 35) Lima, Peru |

| Era | 20th-century |

| Region | Latin American philosophy |

| School | Marxism |

Main interests | Politics, aesthetics |

Influenced

| |

| Signature | |

| |

Life and works

One of three children, José Carlos Mariátegui was born in Moquegua, although his pious Catholic mother, María Amalia La Chira Ballejos, led him to believe he was born in Lima.[3] His father, Francisco Javier Mariátegui Requejo, abandoned his family when José Carlos was young. To support her children, José Carlos' mother, moved first to Lima, then to Huacho, where she had more relatives who helped her make a living. José Carlos had a brother and a sister: Julio César and Guillermina. In 1902, as a young schoolboy, he badly injured his left leg in an accident and was moved to a hospital in Lima. Despite a four-year-long convalescence, his leg remained fragile and he was unable to continue his studies. This was the first of a series of health problems that plagued him throughout his life. Although he was unable to continue formal schooling, Mariátegui read widely and taught himself French.[4]

Though he hoped to become a Roman Catholic priest, at the age of fourteen he started working at a newspaper, first as an errand boy, then as a linotypist, then eventually as a writer. The linotypist he assisted, Juan Manuel Campos, introduced him to an anarchist intellectual, Manuel González Prada. González Prada had made a name for himself in a denunciation of the corruption and incompetence of Peru's rulers, and especially the condition of Peruvian peasants due to the monopolization of land by a small group of gamonales (landowners), an analysis that influenced Mariátegui's later writings.[5] Mariátegui worked in daily journalism for La Prensa and also for the magazine Mundo Limeño. In 1916, he left his first employer to join a new daily, El Tiempo, which had a more leftist orientation. Two years later he launched his magazine, only to find that the owners of El Tiempo refused to print it. This led him to break with El Tiempo and launch a newspaper called La Razón, which became his first major venture in left-wing journalism. In 1918, "nauseated by Creole politics," he wrote in an autobiographical note, "I turned resolutely toward socialism".

The newspaper led by Mariátegui waged a vigorous defense of the campaign then underway for reform of the universities and went on to become a tribunal for the defense of the young labor movement. La Razón supported a strike for the eight-hour day held in May 1919, along with lowering the cost of subsistence goods. The paper’s aggressive radicalism brought it into conflict with the Leguía government, and it was rumored that the ruling circles gave Mariátegui a choice: exile or jail.[6] In any event, Mariátegui left for Europe in 1920, traveling through France, Germany, Austria and eventually living in Italy for two years. In France, he met with Georges Sorel. He was rather taken with the voluntarist, unorthodox Marxism of Sorel, which he saw the qualities of in the rise of Lenin and the Bolsheviks.[7] During his time in Italy, he married an Italian woman, Anna Chiappe,[8] with whom he had four children. He was in Italy during the Turin factory occupations of 1920, and in January 1921 he was present at the Livorno Congress of the Italian Socialist Party, where the historic split occurred that led to the formation of the Communist Party. By the time he left the country in 1922, Benito Mussolini was already on his way to power.

In his writings from that period, Mariátegui observed that fascism was a response to deep social crisis, that it based itself on the petty bourgeoisie of town and country, and that it relied heavily on a cult of violence. According to him, fascism was the price that a society in crisis paid for the failures of the left.

Upon his return to Peru in 1923, he began giving in lectures to the Student Federation in the People’s University and writing articles about the European situation. He also began using Marxist methods to study Peru. Mariátegui also came into contact with and allied himself with Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, leader of the populist movement American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA). In October 1923, Haya de la Torre was deported by the Leguía government, leaving Mariátegui as the editor of the magazine Claridad. The fifth issue of the publication in March 1924 was dedicated to Vladimir Lenin.

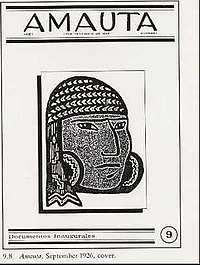

In 1924, Mariátegui nearly died, and his injured leg had to be amputated. In 1926, he established the journal Amauta to serve as a forum for discussions of socialism, art, and culture in Peru and all of Latin America. In 1927, he was arrested and confined to a military hospital, and later subject to house arrest. He briefly considered relocating to Montevideo or Buenos Aires.

In 1928, Mariátegui became alienated from the APRA, and he set about establishing the Socialist Party, which formally constituted in October of that year, with Mariátegui as general secretary (it later became the Communist Party of Peru). That year, he published his best-known work, Seven Interpretative Essays on Peruvian Reality, in which he examined Peru's social and economic situation from a Marxist perspective. It was considered one of the first materialist analyses of a Latin American society. Beginning with the country’s economic history, the book proceeds to a discussion of the "Indian problem", which Mariátegui locates firmly within the "land problem". Other essays are devoted to public education, religion, regionalism and centralism, and literature.

Also in the same work, Mariátegui blamed the latifundistas, or large land-owners, for the stilted economy of the country and the miserable conditions of the indigenous peoples in the region. He observed that Peru at the time had many characteristics of a feudal society. He argued that a transition to socialism should be based on traditional forms of collectivism as practiced by the Indians. In a famous phrase, Mariátegui stated "the communitarianism of the Incas cannot be denied or disparaged for having evolved under an autocratic regime."

In 1929, Mariátegui participated in the establishment of the General Confederation of Peruvian Workers (CGTP), which then sent a delegate to Montevideo for the Constituent Congress of the Latin American Trade Union Conference.

Mariátegui died on April 16, 1930, in Lima of complications from his earlier affliction. His house at Jirón Washington in the center of Lima was later turned into a museum.

Influence

In different ways, organizations like Shining Path, and the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, and the Peruvian Communist Party all look towards Mariátegui and his writings.

Mariátegui's ideas have recently seen a major revival due to the rise of leftist governments all over South America, in particular in Bolivia was in 2005 Evo Morales became that country's first-ever indigenous president since the Conquest 500 years earlier (second in Latin America following Mexico's Benito Juárez). The rise of popular indigenous movements in Ecuador and Peru have also sparked a renewed interest in Mariátegui's writings concerning the role of indigenous peoples in a Latin American revolution. The previous ruling party in Peru, the Peruvian Nationalist Party, claims Mariátegui as one of its ideological founders.[9]

Quotes

- Italian fascism represents, clearly, the anti-revolution or, as it is usually called, the counter-revolution. The fascist offensive is explained and is realized in Italy, as a consequence of a retreat or a defeat of the revolution.

- I am self-taught. I once registered in Arts in Lima, but only in the interest of taking an erudite Augustine’s Latin course. And, in Europe, I freely attended some courses, but without ever deciding to lose my extra-collegiate, and perhaps anti-collegiate, status.[10]

- Peru is a semi-feudal and semi-colonial country at the same time. Though this may seem like a paradox, this is a fact and has to be changed.

- The fight is long and tough, but together we can make it.

Mariátegui is also responsible for coining the phrase, about Marxism, sendero luminoso al futuro ("the Shining Path to the future"). This phrase later became the name of the Shining Path Maoist terrorist organization in Peru as a means of differentiating them from other Communist groups (they preferred to be called the Communist Party of Peru).

Works

- The Heroic and Creative Meaning of Socialism José Carlos Mariátegui. Selected Essays. - Edited and Translated by Michael Pearlman. 1996 Humanities Press, New Jersey

- Seven Interpretive Essays on Peruvian Reality by José Carlos Mariátegui. University of Texas Press. 1997. ISBN 978-0292701151

Further reading

- Chang-Rodríguez, Eugenio. Poética e ideología en José Mariátegui. 1983.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. "Indigenous Resistance in the Americas and the Legacy of Mariátegui". Monthly Review vol. 61(4)2009.

- Krauze, Enrique. "José Carlos Mariátegui: Indigenous Marxism" in Redeemers: Ideas and Power in Latin America. Translated by Hank Heifetz and Natasha Wimmer. New York: HarperCollins 2011.

- Vanden, Harry E. National Marxism in Latin America: José Carlos Mariátegui's Thought and Politics. 1986.

References

- Enrique Krauze, "José Carlos Mariátegui: Indigenous Marxism" in Redeemers: Ideas and Power in Latin America. Translated by Hank Heifetz and Natasha Wimmer. New York: HarperCollins 2011, p. 89.

- Eugenio Chang-Rodríguez, "José Carlos Mariátegui" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 3, p. 523. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Krauze, "Mariátegui", p. 90.

- Krauze, "Mariátegui", p. 91.

- Krauze, "Mariátegui", p. 92.

- Krauze, "Mariátegui" p. 97.

- Vanden, Harry (2011). José Carlos Mariátegui: An Anthology. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 9781583672457.

- Chang-Rodríguez, "José Carlos Mariátegui" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 3, p. 522.

- "Bases Ideológicas". Partido Nacionalista Peruano. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- José Carlos Mariátegui, Autobiographical Note. January 10, 1927.

External links

- José Carlos Mariátegui Online Archive

- José Carlos Mariátegui Memorial Museum, Lima

- José Carlos Mariátegui Film Archive

- José Carlos Mariátegui Complete Photo Archive

- José Carlos Mariátegui Main Internet Portal

- José Carlos Mariátegui Internet Archive (articles, biography, and pictures)

- "José Carlos Mariátegui: Latin America’s forgotten Marxist" an introduction to Mariátegui's life and political views by Mike Gonzalez from International Socialism 115 (summer 2007)

- Indigenous Resistance in the Americas and the Legacy of Mariátegui by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Monthly Review