Jainism in Tamil Nadu

Jainism in Tamil Nadu is about the origin, flourishment and present status of the religion in the state.

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major sects |

|

Texts |

|

Festivals

|

|

|

History

Early Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions in Tamil Nadu date to the 3rd century BCE and describe the livelihoods of Tamil Jains. Inscriptions dating back to eighth century CE were found in Trichy narrating the presence of Jain monks in the region.[1]

Present demography

Tamil Jains are Digambara Jains residing in Tamil Nadu. They are a microcommunity of around 85,000 (around 0.13% of the population of Tamil Nadu). Tamil Jains are predominantly scattered in northern Tamil Nadu, largely in the districts of Madurai, Viluppuram, Kanchipuram, Vellore, Tiruvannamalai, Cuddalore and Thanjavur.

Royal patronage

.jpg)

Kalabhra dynasty ruled over the entire ancient Tamil country between the 3rd and the 7th century were patrons of Jainism.[2]

Pallavas followed Hinduism but also patronised Jainism. Trilokyanatha Temple in Kanchipuram and Chitharal Jain Temple were built during the reign of the Pallava dynasty.[3][4]

The Pandyan kings were Jains in their early ages but later became Shaivaites.[5] Strabo states that an Indian king called Pandion sent Augustus Caesar "presents and gifts of honour".[6] Sittanavasal Cave, Samanar Malai were built during the reign of Pandyan dynasty

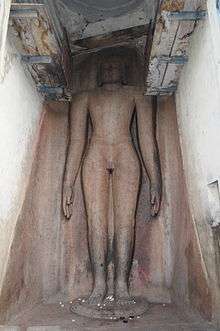

Cholas patronised Hinduism, however, Jainism also flourished during their rule.[7] Construction of Tirumalai cave complex was commissioned Queen Kundavai, elder sister of Rajaraja Chola I. Tirumalai cave complex consist of 3 Jain caves, 2 Jain temples and a 16 metres (52 ft) high sculpture of Tirthankara Neminatha which is the tallest idol of Neminatha and largest Jain idol in Tamil Nadu. Thirakoil and Mannargudi Mallinatha Swamy Jain Temple were built during the reign of the Chola dynasty.

Art

Influence on Tamil literature

Parts of the Sangam literature in Tamil is attributed to Jaina authors. The authenticity and interpolations are controversial, because the Sangam literature presents Hindu ideas.[8] Some scholars state that the Jain portions of the Sangam literature was added about or after the 8th-century CE, and it is not the ancient layer.[9]

Tamil Jain texts such as the Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi and Nālaṭiyār are credited to Digambara Jain authors.[10][11] These texts have seen interpolations and revisions. For example, it is generally accepted now that the Jain nun Kanti inserted a 445 verse poem into Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi in the 12th-century.[12][13] The Tamil Jain literature, states Dundas, has been "lovingly studied and commented upon for centuries by Hindus as well as Jains".[11] The themes of two of the Tamil epics, including the Silapadikkaram, have an embedded influence of Jainism.[11]

Silappatikaram, the earliest surviving epic in Tamil literature, was written by a Samaṇa, Ilango Adigal. This epic is a major work in Tamil literature, describing the historical events of its time and also of then-prevailing religions, Jainism, Buddhism and Shaivism. The main characters of this work, Kannagi and Kovalan, who have a divine status among Tamils, were Jains.

The Jains of Tamil Nadu have contributed so much so, that the then Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu and an important figure in modern Tamil literature M. Karunanidhi said, in an official Government release made, on 23-12-1974 "The virtuous Jains have adorned our ‘Tamil mother’ with innumerable jewels of literary works. If you remove these works of Samanars, the world of Tamil literature would wear a deserted look; such is the contribution of Jain poets to the Tamil language. The ancient kings have also encouraged and supported these noble efforts."[14]

Temples

There are 26 caves, 200 stone beds, 60 inscriptions, and over 100 sculptures in and around Madurai. This is also the site where Jain ascetics wrote great epics and books on grammar in Tamil.[15]

The Sittanavasal Cave temple is regarded as one of the finest examples of Jain art. It is the oldest and most famous Jain centre in the region. It possesses both an early Jain cave shelter, and a medieval rock-cut temple with excellent fresco paintings comparable to Ajantha paintings; the steep hill contains an isolated but spacious cavern. Locally, this cavern is known as "Eladipattam", a name that is derived from the seven holes cut into the rock that serve as steps leading to the shelter. Within the cave there are seventeen stone beds aligned in rows; each of these has a raised portion that could have served as a pillow-loft. The largest stone bed has a distinct Tamil-Brahmi inscription assignable to the 2nd century BCE, and some inscriptions belonging to the 8th century BCE are also found on the nearby beds. The Sittannavasal cavern continued to be the "Holy Sramana Abode" until the 7th and 8th centuries. Inscriptions over the remaining stone beds name mendicants such as Tol kunrattu Kadavulan, Tirunilan, Tiruppuranan, Tittaicharanan, Sri Purrnacandran, Thiruchatthan, Ilangowthaman, Sri Ulagathithan, and Nityakaran Pattakali as monks.[16]

The 8th century Kazhugumalai temple marks the revival of Jainism in Tamil Nadu. This cave temple was built by King Parantaka Nedunjadaiya of Pandyan dynasty.[17]

Mel Sithamur Jain Math is headed by the primary religious head of this community, Bhattaraka Laxmisena Swami.[18]

Decline

Royal patronage has been a key factor in the growth as well as decline of Jainism.[19] The Pallava king Mahendravarman I (600–630 CE) converted from Jainism to Shaivism under the influence of Appar.[20] His work Mattavilasa Prahasana ridicules certain Shaiva sects and the Buddhists and also expresses contempt towards Jain ascetics.[21] Sambandar converted the contemporary Pandya king to Shaivism. During the 11th century, Basava, a minister to the Jain king Bijjala, succeeded in converting numerous Jains to the Lingayat Shaivite sect. The Lingayats destroyed various temples belonging to Jains and adapted them to their use.[22] The Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana (c. 1108–1152 CE) became a follower of the Vaishnava sect under the influence of saint Ramanuja, after which Vaishnavism grew rapidly.[23]

Jain Caves and Stone Beds

- Tirumalai (Jain complex)

- Kalugumalai Jain Beds

- Thirakoil

- Samanar Hills

- Sittanavasal Cave

- Armamalai Cave

- Mangulam

- Kurathimalai, Onampakkam

- Panchapandavar Malai

- Seeyamangalam

- Kanchiyur Jain cave and stone beds

- Andimalai Stone beds, Cholapandiyapuram

- Adukkankal, Nehanurpatti

- Ennayira Malai

The 16 meter statue of Neminath, the tallest Jain sculpture in Tamil Nadu.

The 16 meter statue of Neminath, the tallest Jain sculpture in Tamil Nadu.- Parshvanatha at Thirakoil, 8th Century

- Mahaveer Swami at Kurathimalai, 8th Century AD

- Jain Reliefs at Panchapandava Bed, Kizhavalavu, 9th Century

Image of Mahavira at Samanar Hills, 9th century

Image of Mahavira at Samanar Hills, 9th century Jain Sculptures at Othakakai

Jain Sculptures at Othakakai Chitharal malaikovil, before 425 AD

Chitharal malaikovil, before 425 AD- Mahavir, Parshavanatha and Bahubali, Seeyamangalam, 9th century

Main Temple

- Mel Sithamur Jain Math

- Mannargudi Mallinatha Swamy Temple

- Arahanthgiri Jain Math

- Trilokyanatha Temple

- Karanthai Jain Temple

- Chitharal malaikovil

- Poondi Arugar Temple

- Adisvaraswamy Jain Temple, Thanjavur

- Chandraprabha Jain Temple, Kumbakonam

- Mel Sithamur Jain Math headed by Bhattaraka Laxmisena

Mannargudi Mallinatha Swamy Temple

Mannargudi Mallinatha Swamy Temple Arahanthgiri Jain Math

Arahanthgiri Jain Math Shri Adinatheeswarar Jain Temple, Desur

Shri Adinatheeswarar Jain Temple, Desur.jpg) Shikhar of Thiruparuthikundram temple, Kanchipuram

Shikhar of Thiruparuthikundram temple, Kanchipuram.jpg) Painting at Thiruparuthikundram temple, Kanchipuram

Painting at Thiruparuthikundram temple, Kanchipuram Chitharal Jain Temple

Chitharal Jain Temple Gingee Jain temple, Villupuram district

Gingee Jain temple, Villupuram district

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jainism in Tamil Nadu. |

References

Citation

- "Eighth century artefacts on Jainism at Rockfort lie neglected, damaged", The Times of India, 16 July 2016

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2007). A History of India (4th ed.). London: Routledge. p. 105. ISBN 9780415329200. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- http://www.thehindu.com/thread/arts-culture-society/article8179948.ece

- "Chitharal". Tamil Nadu Tourism. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "Pandya dynasty". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- Sastri 2002, p. 339.

- Cush, Robinson & York 2012, pp. 515, 839.

- Zvelebil 1992, pp. 13–16.

- Cort 1998, p. 163.

- Dundas 2002, p. 116–117.

- Zvelebil 1992, pp. 37–38.

- Spuler 1952, pp. 24–25, context: 22-27.

- https://balpatil.wordpress.com/2010/09/06/jainism-in-tamilnadu-chief-minister-dr-m-karunanidhi-on-jainism-and-tamilnadu/

- S. S. Kavitha (31 October 2012), "Namma Madurai: History hidden inside a cave", The Hindu

- S. S. Kavitha (3 February 2010), "Preserving the past", The Hindu

- "Arittapatti inscription throws light on Jainism", The Hindu, 15 September 2003

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001). Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture. Popular Prakashan. p. 135. ISBN 9788171548392. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- Natubhai Shah 2004, pp. 69–70.

- Lochtefeld 2002, p. 409.

- Arunachalam 1981, p. 170.

- von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 75–77.

- Das 2005, p. 161.

Sources

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1938-1

- Lochtefeld, James G. (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M, 1, The Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8

- Arunachalam, M., ed. (1981), Aintām Ulakat Tamil̲ Mānāṭu-Karuttaraṅku Āyvuk Kaṭṭuraikaḷ, International Association of Tamil Research

- Das, Sisir Kumar (2005), A History of Indian Literature, 500–1399: From Courtly to the Popular, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 978-81-260-2171-0

- Freiberger, Oliver (2006), Asceticism and Its Critics: Historical Accounts and Comparative Perspectives, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-1997-1901-3

- Cort, John E., ed. (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-3785-X

- Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine; York, Michael (2012), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-18978-5

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1992), Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, BRILL Academic, ISBN 90-04-09365-6

- Spuler, Bertold (1952), Handbook of Oriental Studies, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-04190-7

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Sastri, K. A. N. (2002) [1955], A History of South India: From Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar, Oxford University Press

.jpg)