Jain literature

Jain literature comprises Jain Agamas and subsequent commentaries on them by various Jain ascetics. Jain literature is primarily divided between Digambara literature and Śvētāmbara literature. Jain literature exists mainly in Magadhi Prakrit, Sanskrit, Marathi, Tamil, Rajasthani, Dhundari, Marwari, Hindi, Gujarati, Kannada, Malayalam, Tulu and more recently in English.

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major sects |

|

Texts |

|

Festivals

|

|

|

History

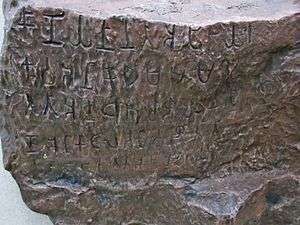

Jain literature was transmitted through oral tradition and consisted of teachings of Jain leaders like Mahavira.[1] After Bhadrabahu, the teachings became inconsistent and differences emerged among Jain leaders due to the scism of religious order into Digambara and Śvētāmbara.[2] After the emigration of large number of Jain monks to south with Bhadrabahu, numerous councils were called to organise the sacred teachings.[2] One of them was organised at Pataliputra.[2] Another was organised in 2nd-century BCE in Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves, Kalinga (now in Odisha) during the reign of Kharavela.[2] The council concluded with the decision to write the teachings, marking the origins of written Jain literature.[2]

Early Jain writers included Gunadhara, Dharasena-Pushpadanta, Kundakunda and Umaswati.[2]

Svetambara leaders organised two councils at Mathura and Valabhi in 4th-century CE.[2] They accepted their canon in Valabhi council of 5th-century CE under the leadership of Devardhigani.[2]

Canonical

The canonical texts of Jainism are called Agamas. These are said to be based on the discourse of the tirthankara, delivered in a samavasarana (divine preaching hall). These discourses are termed as Śrutu Jnāna (Jinvani) and comprises eleven angas and fourteen purvas.[4] According to the Jains, the canonical literature originated from the first tirthankara Rishabhanatha. The Digambara sect believes that there were 26 Agam‑sutras (12 Ang‑agams + 14 Ang‑bahya‑agams). However, they were gradually lost starting from one hundred fifty years after Lord Mahavir's nirvana.[5] Hence, they do not recognize the existing Agam-sutras (which are recognized by the Śvētāmbara sects) as their authentic scriptures.

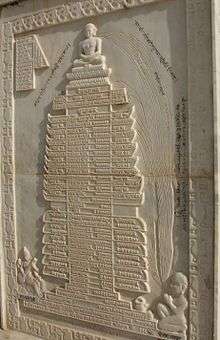

The Jain tradition believes that their religion is eternal, and the teachings of their first Tirthankara Rishabhanatha were their scriptures millions of years ago.[6] The mythology states that the tirthankaras taught in divine preaching halls called samavasarana, which were heard by the gods, the ascetics and laypersons. The discourse delivered is called Śhrut Jnāna (or heard knowledge) and comprises eleven angas and fourteen purvas.[7] The discourse is remembered and transmitted by the Ganadharas (chief disciples), and is composed of twelve angas (departments). It is symbolically represented by a tree with twelve branches.[8]

According to the Jain tradition, an araha (worthy one) speaks meaning that is then converted into sūtra (sutta) by his disciples, and from such sūtras emerge the doctrine.[9] The creation and transmission of the Agama is the work of disciples in Jainism. These texts, historically for Jains, have represented the truths uttered by their tirthankaras, particularly the Mahāvīra.[9] In every cycle of Jain cosmology, twenty-four tirthankaras appear and so do the Jain scriptures for that ara.[6] These then become coded into duvala samgagani pidaga (twelve limbed baskets by disciples), but transmitted orally.[10] In the 980th year after Mahāvīra's death (~5th century CE), the texts were written down for the first time by the Council of Valabhi.[11]

Agama is a Sanskrit word which signifies the 'coming' of a body of doctrine by means of transmission through a lineage of authoritative teachers. They are believed to have been verbally transmitted by the oral tradition from one generation to the next, much like the ancient Buddhist and Hindu texts.[10] The Jain tradition believes that their religion is eternal, and the teachings of their first Tirthankara Rishabhanatha were their scriptures millions of years ago.[6] The religion states that the tirthankara taught in a divine preaching hall called samavasarana, which were heard by the gods, the ascetics and laypersons.

According to the Jain tradition, an araha (worthy one) speaks meaning that is then converted into sūtra (sutta) by his disciples, and from such sūtras emerge the doctrine.[9] The creation and transmission of the Agama is the work of disciples in Jainism. These texts, historically for Jains, have represented the truths uttered by their tirthankaras, particularly the Mahāvīra.[9] In every cycle of Jain cosmology, twenty-four tirthankaras appear and so do the Jain scriptures for that ara.[6] The spoken scriptural language is believed to be Ardhamagadhi by the Śvētāmbara Jains, and a form of sonic resonance by the Digambara Jains. These then become coded into duvala samgagani pidaga (twelve limbed baskets by disciples), but transmitted orally.[10] In the 980th year after Mahāvīra's death (~5th century CE), the texts were written down for the first time by the Council of Valabhi.[11] The Śvētāmbaras believe that they have the original Jain scriptures. This is denied by the Digambaras sect which believes that Āchārya Bhutabali(1st Century CE) was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original canon. Āchārya Bhutabali along with Āchārya Pushpadanta wrote Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama which is a canonical text to Digambaras. The Śvētāmbaras state that their collection of 45 works represent a continuous tradition, though they accept that their collection is also incomplete because of a lost Anga text and four lost Purva texts.[12] According to von Glasenapp, the Digambara texts partially agree with the enumerations and works of older Śvētāmbara texts, but in many cases there are also gross differences between the texts of the two major Jain traditions.[13] Āchāryas recreated the oldest-known Digambara Jain texts, including the four anuyoga.[14][15][16]

The Śvētāmbara consider their 45 text collection as canonical.[12] The Digambaras created a secondary canon between 600 and 900 CE, compiling it into four groups: history, cosmography, philosophy and ethics.[17] This four-set collection is called the "four Vedas" by the Digambaras.[17][lower-alpha 1]

The most popular and influential texts of Jainism have been its non-canonical literature. Of these, the Kalpa Sūtras are particularly popular among Śvētāmbaras, which they attribute to Bhadrabahu (c. 300 BCE). This ancient scholar is revered in the Digambara tradition, and they believe he led their migration into the ancient south Karnataka region, and created their tradition.[19] Śvētāmbaras disagree, and they believe that Bhadrabahu moved to Nepal, not into peninsular India.[19] Both traditions, however, consider his Niryuktis and Samhitas as important texts. The earliest surviving Sanskrit text by Umaswati called the Tattvarthasūtra is considered authoritative Jain philosophy text by all traditions of Jainism. [20][21][22] His text has the same importance in Jainism as Vedanta Sūtras and Yogasūtras have in Hinduism.[23][20][24]

In the Digambara tradition, the texts written by Kundakunda are highly revered and have been historically influential.[25][26][27] Other important Jain texts include: Samayasara, Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra, and Niyamasara.[28]

Digambara literature

In Digambara tradition, two main texts, three commentaries on main texts, and four Anuyogas (exposition) consisting of more than 20 texts are followed.[29] These scriptures were written by great Acharyas (scholars) from 5th to 14th century CE using the original Agama Sutras as the basis for their work.[30] According to Vijay. K. Jain:

Āchārya Bhutabali was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original canon. Later on, some learned Āchāryas started to restore, compile and put into written words the teachings of Lord Mahavira, that were the subject matter of Agamas. Āchārya Dharasen, from 3rd to 7th century CE, guided two Āchāryas, Āchārya Pushpadant and Āchārya Bhutabali, to put these teachings in the written form. The two Āchāryas wrote, on palm leaves, Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama- among the oldest known Digambara Jaina texts. Around the same time, Āchārya Gunadhar wrote Kaşāyapāhuda. [31]

The prathmanuyoga (first exposition) contains the universal history, the karananuyoga (calculation exposition) contains works on cosmology and the charananuyoga (behaviour exposition) includes texts about proper behaviour for monks and Sravakas.[29]

The Shatkhandagama is also known as Maha‑kammapayadi‑pahuda or Maha‑karma‑prabhrut. Two Acharyas; Pushpadanta and Bhutabali wrote it around 6th century CE. The second Purva‑agama named Agraya‑niya was used as the basis for this text. The text contains six volumes. Acharya Virasena wrote two commentary texts, known as Dhaval‑tika on the first five volumes and Maha‑dhaval‑tika on the sixth volume of this scripture, around 780 AD.

Acharya Gunadhara wrote the Kasay-pahud on the basis of the fifth Purva‑agama named Jnana‑pravada. Acharya Virasena and his disciple, Jinasena, wrote a commentary text known as Jaya‑dhavala‑tika around 780 AD.[32]

Jain texts believed to be composed by Acharya Kundakunda around 4th century CE. are:[33]

- Samayasāra (The Nature of the Self)

- Niyamasara (The Perfect Law)

- Pancastikayasara

Gommatsāra is one of the most important Jain texts authored by Acharya Nemichandra Siddhanta Chakravarti.[34] It is based on the major Jain text, Dhavala written by the Acharya Bhutabali and Acharya Pushpadanta.[35] It is also called Pancha Sangraha, a collection of five topics:[36]

- That which is bound, i.e., the Soul (Bandhaka);

- That which is bound to the soul;

- That which binds;

- The varieties of bondage;

- The cause of bondage.

Non-Canonical

Theological

Bhadrabahu (c. 300 CE) is considered by the Jains as last sutra-kevali (one who has memorized all the scriptures). He wrote various books known as niyukti, which are commentaries on those scriptures.[37] He also wrote Samhita, a book dealing with legal cases. Umaswati (c. 1st century CE) wrote Tattvarthadhigama-sutra which briefly describes all the basic tennets of Jainism. Haribhadra (c 8th century) wrote the Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya, a key Jain text on Yoga which compares the Yoga systems of Buddhists, Hindus and Jains. Siddhasena Divakara (c. 650 CE), a contemporary of Vikramaditya, wrote Nyayavatra a work on pure logic.

Hemachandra (c. 1088-1172 CE) wrote the Yogaśāstra, a textbook on yoga and Adhatma Upanishad. His minor work Vitragastuti gives outlines of the Jaina doctrine in form of hymns. This was later detailed by Mallisena (c. 1292 CE) in his work Syadavadamanjari. Devendrasuri wrote Karmagrantha which discuss the theory of Karma in Jainism. Gunaratna (c. 1400 CE) gave a commentary on Haribhadra's work. Lokaprakasa of Vinayavijaya and pratimasataka of Yasovijaya were written in c. 17th century CE. Lokaprakasa deals with all aspects of Jainism. Pratimasataka deals with metaphysics and logic. Yasovijaya defends idol-worshiping in this work. Srivarddhaeva (aka Tumbuluracarya) wrote a Kannada commentary on Tattvarthadigama-sutra. This work has 96000 verses. Jainendra-vyakarana of Acharya Pujyapada and Sakatayana-vyakarana of Sakatayana are the works on grammar written in c. 9th century CE. Siddha-Hem-Shabdanushasana" by Acharya Hemachandra (c. 12th century CE) is considered by F. Kielhorn as the best grammar work of the Indian middle age. Hemacandra's book Kumarapalacaritra is also noteworthy.

Narrative literature and poetry

Jaina narrative literature mainly contains stories about sixty-three prominent figures known as Salakapurusa, and people who were related to them. Some of the important works are Harivamshapurana of Jinasena (c. 8th century CE), Vikramarjuna-Vijaya (also known as Pampa-Bharata) of Kannada poet named Adi Pampa (c. 10th century CE), Pandavapurana of Shubhachandra (c. 16th century CE).

Mathematics

Jain literature covered multiple topics of mathematics around 150 AD including the theory of numbers, arithmetical operations, geometry, operations with fractions, simple equations, cubic equations, bi-quadric equations, permutations, combinations and logarithms.[38]

Languages

Jains literature exists mainly in Jain Prakrit, Sanskrit, Marathi, Tamil, Rajasthani, Dhundari, Marwari, Hindi, Gujarati, Kannada, Malayalam,[39] Tulu and more recently in English.

Jains have contributed to India's classical and popular literature. For example, almost all early Kannada literature and many Tamil works were written by Jains. Some of the oldest known books in Hindi and Gujarati were written by Jain scholars.

The first autobiography in the ancestor of Hindi, Braj Bhasha, is called Ardhakathānaka and was written by a Jain, Banarasidasa, an ardent follower of Acarya Kundakunda who lived in Agra. Many Tamil classics are written by Jains or with Jain beliefs and values as the core subject. Practically all the known texts in the Apabhramsha language are Jain works.

The oldest Jain literature is in Shauraseni and the Jain Prakrit (the Jain Agamas, Agama-Tulya, the Siddhanta texts, etc.). Many classical texts are in Sanskrit (Tattvartha Sutra, Puranas, Kosh, Sravakacara, mathematics, Nighantus etc.). "Abhidhana Rajendra Kosha" written by Acharya Rajendrasuri, is only one available Jain encyclopedia or Jain dictionary to understand the Jain Prakrit, Ardha-Magadhi and other languages, words, their use and references within oldest Jain literature.

Jain literature was written in Apabhraṃśa (Kahas, rasas, and grammars), Standard Hindi (Chhahadhala, Moksh Marg Prakashak, and others), Tamil (Nālaṭiyār, Civaka Cintamani, Valayapathi, and others), and Kannada (Vaddaradhane and various other texts). Jain versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata are found in Sanskrit, the Prakrits, Apabhraṃśa and Kannada.

Jain Prakrit is a term loosely used for the language of the Jain Agamas (canonical texts). The books of Jainism were written in the popular vernacular dialects (as opposed to Sanskrit which was the classical standard of Brahmanism), and therefore encompass a number of related dialects. Chief among these is Ardha Magadhi, which due to its extensive use has also come to be identified as the definitive form of Prakrit. Other dialects include versions of Maharashtri and Sauraseni.[40]

Influence on Indian literature

Parts of the Sangam literature in Tamil are attributed to Jains. The authenticity and interpolations are controversial because it presents Hindu ideas.[41] Some scholars state that the Jain portions were added about or after the 8th century CE, and are not ancient.[42] Tamil Jain texts such as the Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi and Nālaṭiyār are credited to Digambara Jain authors.[43][44] These texts have seen interpolations and revisions. For example, it is generally accepted now that the Jain nun Kanti inserted a 445-verse poem into Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi in the 12th century.[45][46] The Tamil Jain literature, according to Dundas, has been "lovingly studied and commented upon for centuries by Hindus as well as Jains".[44] The themes of two of the Tamil epics, including the Silapadikkaram, have an embedded influence of Jainism.[44]

Jain scholars also contributed to Kannada literature.[47] The Digambara Jain texts in Karnataka are unusual in having been written under the patronage of kings and regional aristocrats. They describe warrior violence and martial valor as equivalent to a "fully committed Jain ascetic", setting aside Jainism's absolute non-violence.[48]

Jain manuscript libraries called bhandaras inside Jain temples are the oldest surviving in India.[49] Jain libraries, including the Śvētāmbara collections at Patan, Gujarat and Jaiselmer, Rajasthan, and the Digambara collections in Karnataka temples, have a large number of well-preserved manuscripts.[49][50] These include Jain literature and Hindu and Buddhist texts. Almost all have been dated to about, or after, the 11th century CE.[51] The largest and most valuable libraries are found in the Thar Desert, hidden in the underground vaults of Jain temples. These collections have witnessed insect damage, and only a small portion have been published and studied by scholars.[51]

References

Citations

- Natubhai Shah 2004, pp. 39-40.

- Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 40.

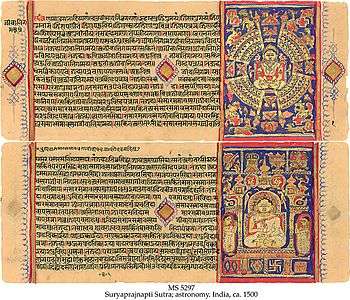

- SuryaprajnaptiSūtra Archived 15 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Schoyen Collection, London/Oslo

- Champat Rai Jain 1929, p. 135.

- Melton & Baumann 2010, p. 1553.

- von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 109–110.

- Champat Rai Jain 1929b, p. 135.

- Champat Rai Jain 1929b, p. 136.

- Dundas 2002, p. 61.

- Dundas 2002, pp. 60–61.

- von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 110–111.

- von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 112–113.

- von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 121–122.

- Vijay K. Jain 2016, p. xii.

- Jaini 1998, p. 78–81.

- von Glasenapp 1925, p. 124.

- von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 123–124.

- Dalal 2010, pp. 164–165.

- von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 125–126.

- Jones & Ryan 2007, pp. 439–440.

- Dundas 2006, pp. 395–396.

- Umāsvāti 1994, p. xiii.

- Johnson 1995, pp. 46–51, 91–96.

- Finegan 1989, p. 221.

- Balcerowicz 2003, pp. 25–34.

- Chatterjee 2000, p. 282–283.

- Jaini 1991, p. 32–33.

- Dundas 2002, p. 80.

- Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. xi-xii.

- Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. xii.

- "Digambar Literature", jainworld.com

- Vijay K. Jain 2012.

- Jaini 1927, p. 5.

- Jaini 1927, p. 3.

- Jaini 1927, p. 2.

- von Glasenapp 1925, p. 175.

- Gheverghese 2016, p. 23.

- Banerjee, Satya Ranjan (2005). Prolegomena to Prakritica et Jainica. The Asiatic Society. p. 61.

- Upinder Singh 2016, p. 26.

- Cush, Robinson & York 2012, pp. 515, 839.

- Zvelebil 1992, pp. 13–16.

- Cort 1998, p. 163.

- Dundas 2002, p. 116–117.

- Zvelebil 1992, pp. 37–38.

- Spuler 1952, pp. 24–25, context: 22–27.

- Cort 1998, p. 164.

- Dundas 2002, pp. 118–120.

- Dundas 2002, p. 83.

- Guy, John (January 2012), "Jain Manuscript Painting", The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Heilburnn Timeline of Art History, archived from the original on 2 April 2013, retrieved 25 April 2013

- Dundas 2002, pp. 83–84.

Sources

- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2003), Essays in Jaina Philosophy and Religion, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1977-1

- Spuler, Bertold (1952), Handbook of Oriental Studies, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-04190-5

- Chatterjee, Asim Kumar (2000), A Comprehensive History of Jainism: From the Earliest Beginnings to AD 1000, Munshiram Manoharlal, ISBN 978-81-215-0931-2

- Cort, John E., ed. (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-3785-8

- Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine; York, Michael (2012), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-18978-5* Gheverghese, Joseph George (2016), Indian Mathematics: Engaging With The World From Ancient To Modern Times, World Scientific, ISBN 9781786340603

- Dalal, Roshen (2010) [2006], The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin books, ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6

- Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine; York, Michael (2012), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-18978-5

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-26605-5

- Dundas, Paul (2006), Olivelle, Patrick (ed.), Between the Empires : Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1

- Finegan, Jack (1989), An Archaeological History of Religions of Indian Asia, Paragon House, ISBN 978-0-913729-43-4

- Jain, Champat Rai (1929), Risabha Deva - The Founder of Jainism, Allahabad: The Indian Press Limited,

- Jain, Champat Rai (1929), The Practical Dharma, The Indian Press Ltd.,

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya: Realization of the Pure Self, With Hindi and English Translation, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-4-5,

- Jain, Vijay K. (2016), Ācārya Samantabhadra's Ratnakarandaka-śrāvakācāra: The Jewel-casket of Householder's Conduct, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-9-0,

- Jaini, Jagmandar-lāl (1927), Gommatsara Jiva-kanda Alt URL

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1991), Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06820-9

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979], The Jaina Path of Purification, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1578-0

- Johnson, W.J. (1995), Harmless Souls: Karmic Bondage and Religious Change in Early Jainism with Special Reference to Umāsvāti and Kundakunda, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1309-0

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9

- Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin, eds. (2010), Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, One: A-B (Second ed.), ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1938-2

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Spuler, Bertold (1952), Handbook of Oriental Studies, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-04190-5

- Umāsvāti, Umaswami (1994), That which is (Translator: Nathmal Tatia), Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-06-068985-8

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1925), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation [Der Jainismus: Eine Indische Erlosungsreligion], Shridhar B. Shrotri (trans.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (Reprint: 1999), ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1992), Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-90-04-09365-2