Islam in Vietnam

Islam in Vietnam is primarily the religion of the Cham people, an Austronesian minority ethnic group; however, roughly one-third of the Muslims in Vietnam are of other ethnic groups.[1][2] There is also a community describing themselves of mixed ethnic origins (Cham, Khmer, Malay, Minang, Viet, Chinese and Arab), who practice Islam and are also known as Cham, or Cham Muslims, around the region of Châu Đốc in the Southwest.[3]

History

Uthman ibn Affan, the third Caliph of Islam, sent the first official Muslim envoy to Vietnam and Tang Dynasty China in 650.[4] Seafaring Muslim traders are known to have made stops at ports in the Champa Kingdom en route to China very early in the history of Islam. After the Tang Dynasty collapsed, Abbasid Caliphate continued trading with the Vietnamese in Annam, later with Đại Việt kingdom.[5] however, the earliest material evidence of the transmission of Islam consists of Song Dynasty-era documents from China which record that the Cham familiarised themselves with Islam in the late 10th and early 11th centuries.[6][7] The number of followers began to increase as contacts with Sultanate of Malacca broadened in the wake of the 1471 collapse of the Champa Kingdom, but Islam would not become widespread among the Cham until the mid-17th century.[8]

On the same time, during the Mongol invasions of Vietnam, several Mongol generals were Muslims, including Omar Nasr al-Din; and the major bulk of Mongol army invading Vietnam came from the Turks and Persians. During their short conquest, the Mongols managed to spread Islam with a minimal decent, although it was never large enough to challenge the Vietnamese.

In the mid-19th century, many Muslim Chams emigrated from Cambodia and settled in the Mekong Delta region, further bolstering the presence of Islam in Vietnam. Malayan Islam began to have an increasing influence on the Chams in the early 20th century; religions publications were imported from Malaya, Malay clerics gave khutba (sermons) in mosques in the Malay language, and some Cham people went to Malayan madrasah to further their studies of Islam.[9][10] The Mekong Delta also saw the arrival of Malay Muslims.[11]

In 1832 the Vietnamese Emperor Minh Mang annexed the last Champa Kingdom. This resulted in the Cham Muslim leader Katip Suma, who was educated in Kelantan to declare a Jihad against the Vietnamese.[12][13][14][15] The Vietnamese coercively fed lizard and pig meat to Cham Muslims and cow meat to Cham Hindus against their will to punish them and assimilate them to Vietnamese culture.[16]

Cham Muslims and Hindus formed the Cham Liberation Front (Front de Liberation du Champa, FLC) led by the Muslim Lieutenant-Colonel Les Kosem to fight against both North and South Vietnam during the Vietnam War in order to obtain Cham independence. The Cham Liberation Front joined with the Montagnards and Khmer Krom to form the United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races (Front Uni de Lutte des Races Opprimées, FULRO) to fight the Vietnamese.

After the 1976 establishment of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, some of the 55,000 Muslim Chams emigrated to Malaysia. 1,750 were also accepted as immigrants by Yemen; most settled in Ta'izz. Those who remained did not suffer violent persecution, although some writers claim that their mosques were closed by the government.[1] In 1981, foreign visitors to Vietnam were still permitted to speak to indigenous Muslims and pray alongside them, and a 1985 account described Ho Chi Minh City's Muslim community as being especially ethnically diverse: aside from Cham people, there were also Indonesians, Malays, Bangladeshis, Pakistanis, Yemenis, Omanis, and North Africans; their total numbers were roughly 10,000 at the time.[8]

Vietnam's second largest mosque was opened in January 2006 in Xuân Lộc, Đồng Nai Province; its construction was partially funded by donations from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the latter has a strong tie to Vietnam.[17] A new mosque, the largest in Vietnam, in An Giang Province, the Kahramanlar Rahmet Mosque, was opened in 2017 with Turkish funds.[18]

According to the Cham advocacy group International Office of Champa (IOC-Champa) and Cham Muslim activist Khaleelah Porome, both Hindu and Muslim Chams have experienced religious and ethnic persecution and restrictions on their faith under the current Vietnamese government, with the Vietnamese state confisticating Cham property and forbidding Cham from observing their religious beliefs. Hindu temples were turned into tourist sites against the wishes of the Cham Hindus. In 2010 and 2013 several incidents occurred in Thành Tín and Phươc Nhơn villages where Cham were murdered by Vietnamese. In 2012, Vietnamese police in Chau Giang village stormed into a Cham Mosque, stole the electric generator.[19] Cham Muslims in the Mekong Delta have also been economically marginalised, with ethnic Vietnamese settling on land previously owned by Cham people with state support.[20]

The Cham Suleiman Idres Bin called for independence of Champa from Vietnam and advocated for international intervention similar as to how East Timor independence was implemented by the United Nations.[21]

Due to the rising pro-American and pro-Western supports in Vietnam, and worrying about the spread of Islamic terrorism on the War on Terror, the United States and the West with other countries like India, Australia, have, instead, strongly supported Vietnam on territorial integrity, since most of Cham people are now Muslims. Adding with what Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and Al-Qaeda have done, and the fears over Myanmar's Rohingya crisis and Islamic insurgency in Thailand, most ignore the Cham's demands.

Demographics

Vietnam's April 1999 census showed 63,146 Muslims. Over 77% lived in the South Central Coast, with 34% in Ninh Thuận Province, 24% in Bình Thuận Province, and 9% in Ho Chi Minh City; another 22% lived in the Mekong Delta region, primarily in An Giang Province. Only 1% of Muslims lived in other regions of the country. The number of believers is gender-balanced to within 2% in every area of major concentration except An Giang, where the population of Muslim women is 7.5% larger than the population of Muslim men.[22] This distribution is somewhat changed from that observed in earlier reports. Prior to 1975, almost half of the Muslims in the country lived in the Mekong Delta, and as late as 1985, the Muslim community in Ho Chi Minh City was reported to consist of nearly 10,000 individuals.[1][8] Of the 54,775 members of the Muslim population over age 5, 13,516, or 25%, were currently attending school, 26,134, or 48%, had attended school in the past, and the remaining 15,121, or 27%, had never attended school, compared to 10% of the general population. This gives Muslims the second-highest rate of school non-attendance out of all religious groups in Vietnam (the highest rate being that for Protestants, at 34%). The school non-attendance rate was 22% for males and 32% for females.[23] Muslims also had one of the lowest rate of university attendance, with less than 1% having attended any institution of higher learning, compared to just under 3% of the general population.[24]

Official representation

The Ho Chi Minh City Muslim Representative Committee was founded in 1991 with seven members; a similar body was formed in An Giang Province in 2004.[10]

Cultural appreciation

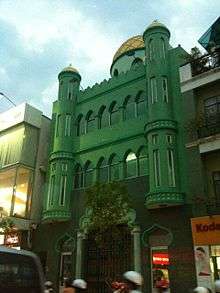

Though Muslim community counted only just 1% of Vietnamese population and has been suffering communist oppression, the Vietnamese regard the Muslim community with a favorable opinion due to its tolerance approach. It's notable that religious worshipping locations, whenever located, can be found easily and get less harassment despite the communist's atheist policy. In Ho Chi Minh City already has five major mosques and a Muslim district.[25]

See also

References

Notes

- Farah 2003, pp. 283–284

- Levinson & Christensen 2002, p. 90

- Taylor 2007

- "Hanoi's Old Quarter a Haven for the Muslim Tourist". Jakarta Globe. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- Hoàng thành Thăng Long (8 August 2013). "10th-century Egyptian and Muslim ceramics found in Hanoi".

- Hourani 1995, pp. 70–71

- GCRC 2006, p. 24

- Taouti 1985, pp. 197–198

- Teng 2005

- GCRC 2006, p. 26

- Philip Taylor (2007). Cham Muslims of the Mekong Delta: Place and Mobility in the Cosmopolitan Periphery. NUS Press. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-9971-69-361-9.

- Jean-François Hubert (8 May 2012). The Art of Champa. Parkstone International. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-1-78042-964-9.

- "The Raja Praong Ritual: A Memory of the Sea in Cham- Malay Relations". Cham Unesco. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- (Extracted from Truong Van Mon, “The Raja Praong Ritual: a Memory of the sea in Cham- Malay Relations”, in Memory And Knowledge Of The Sea In South Asia, Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences, University of Malaya, Monograph Series 3, pp, 97-111. International Seminar on Maritime Culture and Geopolitics & Workshop on Bajau Laut Music and Dance”, Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, 23-24/2008)

- Dharma, Po. "The Uprisings of Katip Sumat and Ja Thak Wa (1833-1835)". Cham Today. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- "Xuan Loc district inaugurates the biggest Minster for Muslim followers", Dong Nai Radio and Television Station, 2006-01-16, archived from the original on 2007-09-27, retrieved 2007-03-29

- "Turkish aid NGO opens Vietnam's biggest mosque".

- "Mission to Vietnam Advocacy Day (Vietnamese-American Meet up 2013) in the U.S. Capitol. A UPR report By IOC-Campa". Chamtoday.com. 2013-09-14. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

- Taylor, Philip (December 2006). "Economy in Motion: Cham Muslim Traders in the Mekong Delta" (PDF). The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology. The Australian National University. 7 (3): 238. doi:10.1080/14442210600965174. ISSN 1444-2213. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Suleiman Idres Bin (12 September 2011). "The case of the fallen Champa". IOC-Champa. Archived from the original on 7 June 2012.

- Census 1999, Table & 83

- Census 1999, Table & 93

- Census 1999, Table 104

- "Top 5 Mosques in Ho Chi Minh City".

Sources

- Taylor, Philip (2007), Cham Muslims of the Mekong Delta: Place and Mobility in the Cosmopolitan Periphery, NUS Press, Singapore, ISBN 978-9971-69-361-9

- De Feo, Agnès (2006), Trangressions de l'islam au Vietnam, Cahiers de l'Orient n°83, Paris

- Religion and policies concerning religion in Vietnam, Hanoi, Vietnam: Government Committee for Religious Affairs, 2006, archived from the original on 2011-05-15, retrieved 2007-03-29

- Teng, Chengda (2005), 当代越南占族与伊斯兰教 [Modern Vietnam's Cham People and Islam], 西北第二民族学院学报 [Journal of the #2 Northwest Nationalities Academy] (in Chinese), 1

- Farah, Caeser E. (2003), Islam:Beliefs and Observances, Barron's, ISBN 0-7641-2226-6

- Hourani, George Fadlo (1995), Arab Seafaring (expanded ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-00032-8

- Levinson, David; Christensen, Karen (2002), Encyclopedia of Modern Asia, Thomson Gale, ISBN 0-684-31247-6

- Taouti, Seddik (1985), "The Forgotten Muslims of Kampuchea and Viet Nam", in Datuk Ahmad Ibrahim; Yasmin Hussain; Siddique, Sharon (eds.), Readings on Islam in Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 193–202, ISBN 9971988089

Census tables

- Table 83: Muslim believers as of 1 April 1999 by province and by sex (Excel), Tổng Cục Thống kê Việt Nam, 1999-04-01, retrieved 2007-03-29

- Table 93: Population aged 5 and over as of 1 April 1999 by religion, by sex and by school attendance (Excel), Tổng Cục Thống kê Việt Nam, 1999-04-01, retrieved 2007-03-29

- Table 104: Population aged 5 and over as of 1 April 1999 by religion, by sex and by education level (Attending/attended) (Excel), Tổng Cục Thống kê Việt Nam, 1999-04-01, retrieved 2007-03-29

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Islam in Vietnam. |