Internet censorship in Vietnam

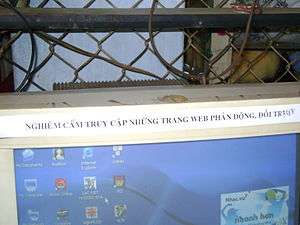

Internet censorship in Vietnam prevents access to websites critical of the Vietnamese government, expatriate political parties, and international human rights organizations, among others or anything the Vietnamese government doesn't agree with.[1] Online police reportedly monitor Internet cafes and cyber dissidents have been imprisoned. Vietnam regulates its citizens' Internet access using both legal and technical means. The government's efforts to regulate, monitor, and provide oversight regarding Internet use has been referred to as a "Bamboo Firewall".[2] However, citizens can usually view, comment and express their opinions civilly on the internet, as long as it does not evoke anti-government movement, political coup and disrupt the social stability of the country.

The OpenNet Initiative classified the level of filtering in Vietnam as pervasive in the political, as substantial in the Internet tools, and as selective in the social and conflict/security areas in 2011,[3] while Reporters without Borders consider Vietnam an "internet enemy".[1][4]

While the government of Vietnam claims to safeguard the country against obscene or sexually explicit content through its blocking efforts, many of the filtered sites contain no such content, but rather politically or religiously critical materials that might undermine the Communist Party and the stability of its one-party rule.[5] Amnesty International reported many instances of Internet activists being arrested for their online activities.[6]

Background

Vietnam's Internet regulation commenced in large part as a result of the government's 1997 decree concerning Internet usage, wherein the General Director of the Postal Bureau (DGPT) was granted exclusive regulatory oversight of the Internet.[2] As a result, the DGPT regulated every aspect of the Internet, including the registration and creation of Internet Service Providers, and the registration of individuals wishing to use the Internet through subscription contracts.

Legal framework

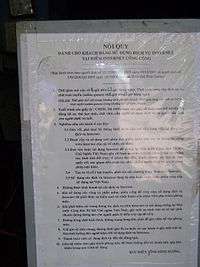

Regulatory responsibility for Internet material is divided along subject-matter lines with the Ministry of Culture and Information focusing on sexually explicit, superstitious, or violent content, while the Ministry of Public Security monitors politically sensitive content. Vietnam nominally guarantees freedom of speech, of the press, and of assembly through constitutional provisions, but state security laws and other regulations reduce or eliminate these formal protections in practice. All information stored on, sent over, or retrieved from the Internet must comply with Vietnam's Press Law, Publication Law, and other laws, including state secrets and intellectual property protections. All domestic and foreign individuals and organizations involved in Internet activity in Vietnam are legally responsible for content created, disseminated, and stored. It is unlawful to use Internet resources or host material that opposes the state; destabilizes Vietnam's security, economy, or social order; incites opposition to the state; discloses state secrets; infringes organizations’ or individuals’ rights; or interferes with the state's Domain Name System (DNS) servers. Law on Information Technology was enacted in June 2006. Those who violate Internet use rules are subject to a range of penalties, from fines to criminal liability for offenses such as causing chaos or security order.[7]

A 2010 law required public Internet providers, such as Internet cafes, hotels, and businesses providing free Wi-Fi, to install software to track users' activities.[8][9]

In September 2013, Decree 72 came into effect; making it illegal to distribute any materials online that "harms national security” or “opposes" the government, only allows users to "provide or exchange personal information" through blogs and social media outlets—banning the distribution of "general information" or any information from a media outlet (including state-owned outlets), and requires that foreign web companies operate servers domestically if they target users in Vietnam.[10]

Censored content

Subversive content

OpenNet research found that blocking is concentrated on websites with contents about overseas political opposition, overseas and independent media, human rights, and religious topics.[3] Proxies and circumvention tools, which are illegal to use, are also frequently blocked.

The majority of blocked websites are specific to Vietnam: those written in Vietnamese or dealing with issues related to Vietnam.[3] Sites not specifically related to Vietnam or only written in English are rarely blocked. For example, the Vietnamese-language version of the website for Radio Free Asia was blocked by both tested ISPs while the English-language version was only blocked by one.[3] While only the website for the human rights organization Human Rights Watch was blocked in the tested list of global human rights sites, many Vietnamese-language sites only tangentially or indirectly critical of the government were blocked as well as sites strongly critical of the government.

The website of the British Broadcasting Corporation (www.bbc.co.uk), which has a significant journalistic presence, is an example of a website that is blocked—albeit intermittently.

Pornography

Although "obscene" content is one of the main reasons cited by the government to censor the Internet, in fact very few websites with pornography are censored in Vietnam. This shows that censorship is in fact not for government reasons. A study by OpenNet in 2006 showed that no websites with pornography were blocked (except for a site containing a link to a pornography site, but was blocked for other reasons).[11] When some sites such as Facebook and YouTube are considered by the media representatives in Vietnam to be blocked due to economic reasons because accounting for 70% -80% of international bandwidth runs through without bringing profits to the home. At the same time, some local feedback asked if thousands of porn websites were profitable for the network without being blocked. In November 2019, Vietnam Internet Service Provider such as Viettel, VNPT, FPT Telecom, etc. may have blocked a mass of porn sites silently or officially.

Social networking

The popular social networking website Facebook has about 8.5 million users in Vietnam and its user base has been growing quickly after the website added a Vietnamese-language interface.[12] During the week of November 16, 2009, Vietnamese Facebook users reported being unable to access the website.[13] Access had been intermittent in the previous weeks, and there were reports of technicians ordered by the government to block access to Facebook.

A supposedly official decree dated August 27, 2009, was earlier leaked on the Internet, but its authenticity has not been confirmed. The Vietnamese government denied deliberately blocking access to Facebook, and the Internet service provider FPT said that it is working with foreign companies to solve a fault blocking to Facebook's servers in the United States.[14]

Blogging

In Vietnam, Yahoo! 360° was a popular blogging service. After the government crackdown on journalists reporting on corruption in mid-2008, many blogs covered the events, often criticizing the government action. In response, the Ministry of Information proposed new rules that would restrict blogs to personal matters.[15]

Global Voices Advocacy maintains a list of bloggers who have been arrested for their views expressed online.[16] Other bloggers who have also been arrested by the Vietnamese government for simply expressing their rights can be found on the 2011 crackdown on Vietnamese youth activists.

As of 29 February 2016, the blogging platforms Blogger and Wordpress.com have been blocked using a DNS block. As of 31 October 2016, Twitter is blocked using a DNS block, but was working normally in November 2017.

All of these blocks could be bypassed by configuring computers to use an alternate DNS provider.

Instant messaging

Yahoo! messenger is amongst the instant messaging software that appears to be monitored, with messages often blocked (i.e., not seen by intended recipient).

Criticism of government

In 2019, Vietnam introduced a cybersecurity law that made it illegal to criticize the government online and requires ISPs to hand over user data when requested.[17]

Persecution for illegal Internet activities

A component of Vietnam's strategy to control the Internet consists of the arrest of bloggers, netizens and journalists.[18][19] The goal of these arrests is to prevent dissidents from pursuing their activities, and to persuade others to practice self-censorship. Vietnam is the world's second largest prison for netizens after China.[20]

- Phan Thanh Hai, also known as Anh Ba Saigon, was arrested in October 2010 and later charged with promoting "propaganda against the State" for spreading false information on his blog, where he had discussed topics such as maritime disputes with China and bauxite mining operations, and had actively supported Vietnamese dissidents.

- Blogger Paulus Lê Sơn was arrested on August 3, 2011 in Hanoi for his attempt to cover the trial of the well known cyberdissident Cu Huy Ha Vu.

- Long time dissident and Catholic priest Nguyen Van Ly is a member of the Bloc 8406 pro-democracy movement. He was arrested on 19 February and sentenced on 30 March 2007 to eight years in prison for committing "very serious crimes that harmed national security" by trying to organize a boycott of the upcoming election. He may have suffered a stroke while in prison on 14 November 2009. He was released from prison to receive medical care on 17 March 2010 and was returned to prison in July 2011 despite his age (65) and poor health.

- Blogger Lư Văn Bảy, also known by the pen-names Tran Bao Viet, Chanh Trung, Hoang Trung Chanh, Hoang Trung Viet and Nguyen Hoang, received a four-year prison sentence plus three years of house arrest in September 2011 on a charge of anti-government propaganda under article 88 of the criminal code. Ten articles calling for multiparty democracy, which he had posted online, were cited by the prosecution during the trial. He was not allowed access to a lawyer at his trial.[21]

- Le Cong Dinh, a prominent Vietnamese lawyer who sat on the defense of many high-profile human rights cases in Vietnam and was critical of bauxite mining in the central highlands of Vietnam was arrested by the Vietnamese government on 13 June 2009 under article 88 of Vietnam's criminal code for "conducting propaganda against the government". On 20 January 20, 2010 he was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison for subversion. His co-defendants, Nguyễn Tiến Trung, Trần Huỳnh Duy Thức, and Lê Thang Long received sentences from 7 to 16 years.

- Franco-Vietnamese blogger Pham Minh Hoang was released from prison after serving his 17-month sentence, but remains under a three-year house arrest. He was arrested on 13 August and charged on 20 September 2010 with “carrying out activities with the intent of overthrowing the government" by virtue of Article 79 of the Penal Code, for having joined the banned opposition party, Viet Tan, and publishing on his blog (pkquoc.multiply.com) opposition articles under the pen name Phan Kien Quoc. According to his wife, Le Thi Kieu Oanh, Pham Minh Hoang was arrested because of his opposition to a Chinese company's plans to mine bauxite in central Vietnam's high plateau region.

- Blogger Dieu Cay was arrested in April 2008 and sentenced in September 2008 for "tax fraud". The authorities were actually seeking to silence him after he had publicly called for people to boycott the Ho Chi Minh City leg of the Olympic torch relay on the occasion of Beijing's 2008 Olympic Games. He should have been released in October 2010 after serving his two and one-half year prison sentence. He is still in detention, now charged with propaganda against the State and the Party by virtue of Article 88 of the Vietnamese Penal Code. His relatives have had no news of him for months, leading to widespread alarmist rumors. Whether or not they are well-founded, concerns about his fate and health remain justified as long as the authorities refuse to grant his family visiting rights.

- Blogger Nguyen Van Tinh and poet Tran Duc Thach were released in 2011 after being sentenced in 2009 to three and one-half and three years in prison, respectively, for “propaganda against the socialist state of Vietnam”.

- In February 2017, the Vietnamese government arrested and prosecuted bloggers and citizen journalists in a crackdown, including Nguyễn Văn Oai and Nguyễn Văn Hoá. Hoá was prosecuted to 7 years in prison for reporting about the 2016 Vietnam Marine Life Disaster.[22][23]

- Pham Chi Dung, a prominent independent journalist, chairman of the Vietnam Independent Journalists Society (IJAVN) and founder of the news website vietnamthoibao.org, was arrested on November 21, 2019 by the public security forces of Ho Chi Minh City. He is charged under Article 117 of Vietnam 2015 Criminal Code for “producing, storing, and disseminating” documents opposing the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. While state media asserts that he has participated in “very dangerous and serious conduct that negatively affects national social stability, public order of Ho Chi Minh City,” they can only point out one fact to support that accusation: that he established and organized a “civil society organization.” The arrest of Pham Chi Dung, is the continuation of an intensified crackdown against political activists.

- Nguyen Tuong Thuy, a 68-year-old blogger and IJAVN vice-president, was arrested on 23 May 2020 in Hanoi, where he lives, and was immediately transported 1,700 km south of the capital to Ho Chi Minh City, where he continues to be held. Nguyen Tuong Thuy is a former Vietnamese Communist Party combatant,.Thuy became a reporter for Radio Free Asia, which is funded by the US Congress.

References

- Reporters Without Borders. "Internet Enemies: Vietnam". Archived from the original on 2009-07-02. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- Robert N. Wilkey (Summer 2002). "Vietnam's Antitrust Legislation and Subscription to E-ASEAN: An End to the Bamboo Firewall Over Internet Regulation?". The John Marshall Journal of Computer and Information Law. The John Marshall Law School. XX (4). Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2012-01-11.

- OpenNet Initiative "Summarized global Internet filtering data spreadsheet" Archived 2012-01-10 at the Wayback Machine, 8 November 2011 and "Country Profiles" Archived 2011-08-26 at the Wayback Machine, the OpenNet Initiative is a collaborative partnership of the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto; the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University; and the SecDev Group, Ottawa

- Internet Enemies Archived 2012-03-23 at the Wayback Machine, Reporters Without Borders (Paris), 12 March 2012

- "OpenNet Initiative Vietnam Report: University Research Team Finds an Increase in Internet Censorship in Vietnam". Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. 2006-08-05. Archived from the original on 2008-09-05. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- Amnesty International (2006-10-22). "Viet Nam: Internet repression creates climate of fear". Archived from the original on 2018-11-22. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- "Vietnam country report" Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine, OpenNet Initiative, 9 May 2007

- Harvey, Rachel (2010-08-18). "Vietnam's bid to tame the internet boom". Archived from the original on 2016-09-27. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- Censorship, Index on (2014-02-20). "Internet repression in Vietnam continues as 30-month prison sentence for blogger is upheld". Index on Censorship. Archived from the original on 2019-09-28. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "Just Stick to Celebrity Gossip: Vietnam Bans Discussion of News From Blogs and Social Sites". Time. 2 September 2013. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- "Internet Filtering in Vietnam in 2005-2006: A Country Study". OpenNet Initiative. 2006. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ""Vietnam boasts 30.8 million internet users." Accessed 5-21-2013". Archived from the original on 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- STOCKING, BEN (2009-11-17). "Vietnam Internet users fear Facebook blackout". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2018-03-19. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- Marsh, Vivien (2009-11-20). "Vietnam government denies blocking networking site". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- Ben Stocking (2008-12-06). "Test for Vietnam government: free-speech bloggers". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2008-12-09. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- "Threatened Voices: Bloggers >> Vietnam" Archived 2010-04-17 at the Wayback Machine, Global Voices Advocacy, accessed 20 March 2012

- Vietnam criticised for 'totalitarian' law banning online criticism of government Archived 2019-01-02 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, 2018

- "Vietnam Report" in Enemies of the Internet 2011 Archived 2012-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, Reporters Without Borders

- "Vietnam Report" in Enemies of the Internet 2012 Archived 2012-03-15 at the Wayback Machine, Reporters Without Borders

- 121 Netizens Imprisoned in 2012 Archived 2012-11-10 at the Wayback Machine, Press Freedom Barometer 2012, Reporters Without Borders

- "Blogger Lu Van Bay Serving Four-Year Sentence" Archived 2012-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, Reporters Without Borders, 26 September 2011

- "Document". www.amnesty.org. Archived from the original on 2017-04-26. Retrieved 2017-04-26.

- Paddock, Richard C. (27 November 2017). "Vietnamese Blogger Gets 7 Years in Jail for Reporting on Toxic Spill". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.