Highbridge Park

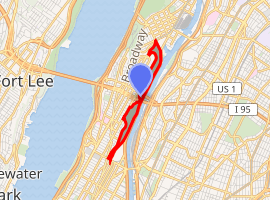

Highbridge Park is a public park located on the western bank of the Harlem River in Washington Heights, Manhattan, New York City. It stretches between 155th Street and Dyckman Street in Upper Manhattan. The park is operated by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. The City maintains the southern half of the park, while the northern half is maintained by the non-profit New York Restoration Project.[1][2] Prominent in the park are the Manhattan end of the High Bridge, the High Bridge Water Tower, and the Highbridge Play Center.

| Highbridge Park | |

|---|---|

Highbridge Play Center | |

| |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | Washington Heights, Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°50′49″N 73°55′48″W |

| Area | 119 acres (48 ha) |

| Created | 1865 |

| Operated by | NYC Parks |

| Public transit access | Subway: Bus: M2, M3, M98, M100, M101, Bx3, Bx6, Bx6 SBS, Bx11, Bx13, Bx35, Bx36 |

History

Early history

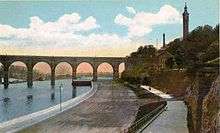

Highbridge Park derives its name from New York City’s oldest standing bridge, the High Bridge (1848), which was built to carry the Old Croton Aqueduct over the Harlem River. From the 17th to the 19th centuries, the area was sparsely populated with scattered farms and private estates. During the American Revolution, General George Washington used the Morris-Jumel Mansion, adjacent to the southern end of the park near Edgecombe Avenue and West 160th Street, as his headquarters in September and October 1776.[3]

The land for Highbridge Park was assembled piecemeal between 1867 and the 1960s. It was designed in 1888 by Samuel Parsons Jr. and Calvert Vaux.[4] The area between 190th and 192nd Streets was occupied by the Fort George Amusement Park, a trolley park/amusement park, from 1895 to 1914; its site is now a seating area in Highbridge Park.[5]

The park was the site of the 1887 USA Cross Country Championships.[6]

In the 1890s, the City of New York built a racetrack for horses, the Harlem River Speedway, along the riverbank of the park.

20th century

Early 20th century

The cliffside area from West 181st Street to Dyckman Street was acquired in 1902, and the parcel including Fort George Hill was acquired in 1928. In 1934 the Department of Parks obtained the Highbridge Tower and the site of the old Highbridge Reservoir.

By the early years of the 20th century, upper-middle class New Yorkers would promenade along the wide boardwalks in top hats and bustles. The park provided access to the Harlem River and places for horseback riding and other outdoor sports. By the 1920s dirt and other materials from the build-up of the new Washington Heights neighborhood threatened to ruin the nascent park; a harbinger of bad times to befall the park.[7]

Works Progress Administration renovation

In 1934, Robert Moses was nominated by mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia to become commissioner of a unified New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. At the time, the United States was experiencing the Great Depression, and immediately after La Guardia won the 1934 election, Moses began to write "a plan for putting 80,000 men to work on 1,700 relief projects".[8][9]:82 By the time he was in office, several hundred projects were underway across the city.[9]:84

Moses was especially interested in creating new pools and other bathing facilities, such as those in Jacob Riis Park, Jones Beach, and Orchard Beach.[10]:456 He devised a list of pools at 11 locations around the city, including at Highbridge Park, which would be built using funds from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a federal agency created to combat the Depression's negative effects as part of the New Deal.[11][10]:456 In total, Moses planned to create 23 pools.[12] He, along with architects Aymar Embury II and Gilmore David Clarke, created a common design for each of the 11 proposed aquatic centers. Each location was to have distinct pools for diving, swimming, and wading; bleachers and viewing areas; and bathhouses with locker rooms that could be used as gymnasiums. The pools were to have several common features, such as a minimum 55-yard (50 m) length, underwater lighting, heating, filtration, and low-cost construction materials. To fit the requirement for cheap materials, each building would be built using elements of the Streamline Moderne and Classical architectural styles. The buildings would also be located near "comfort stations", additional playgrounds, and spruced-up landscapes.[13]

Construction for some of the 11 pools began that October.[13] Highbridge Park was among the first sites that Moses selected; in April 1934, the New York Times had reported that the unused Highbridge and Williamsbridge Reservoirs had been selected for use as park sites.[14] By mid-1936, ten of the eleven WPA funded pools were completed and were being opened at a rate of one per week.[10]:456 Highbridge Park pool opened on July 14, 1936.[15] The complex included a 166-by-288-foot (51 by 88 m) main pool and 166-by-288-foot (51 by 88 m) wading pool.[16]

Later 20th century

.jpg)

In 1940, Moses turned portions of the Speedway into the Harlem River Drive, a 6-lane highway from the Manhattan end of the Triborough Bridge at 125th Street, to the tunnels under Manhattan to the George Washington Bridge. New fences blocked public recreational access to the riverfront. It was this series of actions, according to Parks & Recreation Commissioner Adrian Benepe, that "ruined" the park.[17] The Highbridge Play Center bathhouse was restored in the 1960s, during which the original murals by Charles Clarke were destroyed or covered over.[18] The 1200-foot-long, 116-foot-tall High Bridge walkway was closed to regular public use around 1970.[19]

By the 1970s, Highbridge Park and other city parks were in poor condition due to the 1975 New York City fiscal crisis. Particularly in Highbridge Park, large sections set aside as natural areas, had been taken over by homeless people who built permanent shacks made of sheet metal and steel pipes driven into the earth. Prostitutes, drug dealers and drug users frequented the park.[17] NYC Parks commenced a project to restore the pools in several parks in 1977, including at Highbridge Park, for whose restoration the agency set aside an estimated $5.8 million.[20] These projects were not carried out due to a lack of money, and by March 1981, NYC Parks only had 2,900 employees in its total staff, less than 10 percent of the 30,000 present when Moses was parks commissioner.[20][21] In 1982, the NYC Parks budget increased greatly, enabling the agency to carry out $76 million worth of restoration projects by year's end; among these projects was the restoration of the Highbridge Park pool.[22] The play center and pool were completely renovated over a three-year period following a design by architect Stephen B. Jacobs. The play center reopened on June 14, 1985.[23]

NYC Parks continued to face financial shortfalls in the coming years, and the pools retained a reputation for being unsafe.[24] In June 1984, a man set fire to the Highbridge Tower roof before jumping to his death.[23][25] By the mid-1980s, Highbridge had become so degraded that during a manual cleanup in 1986, 250 tons of garbage and 25 auto wrecks were removed, but garbage again began to fill the park within a matter of days.[4] For the summer of 1991, mayor David Dinkins had planned to close all 32 outdoor pools in the city, a decision that was only reversed after a $2 million donation from real estate developer Sol Goldman[26] and $1.8 million from other sources.[24] Additionally, in the 1990s, a practice called "whirlpooling" became common in New York City pools such as Highbridge Park, wherein women would be inappropriately fondled by teenage boys.[27][28] By the turn of the century, crimes such as sexual assaults had decreased in parks citywide due to increased security.[24]

The condition of Highbridge Park has gotten better, and it is no longer a haven for petty crime and other illegal activities. In November 1991, the water tower was restored.[23][25] The New York Restoration Project, chaired by Bette Midler, has been working since 1999 to restore the park.[29] The park also received a renovation in 1996, which included a $305,000 pool filtration system and a $445,000 renovation of heating and ventilation in the pool area.[23]

21st century

On May 19, 2007, the first legal mountain bike trails and dirt jumps in New York City were opened in Highbridge Park. New York City Mountain Bike Association, working with NYC Parks & Recreation, and the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA), worked to design and install the trails; the opening weekend featured a festival and cross-country mountain bike race.[30][31][32] Around 2010, the waterfront Speedway was rehabilitated and reopened as the Harlem River portion of the Manhattan Waterfront Greenway.

By late 2011, despite the efforts of both the NYRP and NYC Parks, the infrastructure of the park had decayed significantly.[4][33] The city announced plans for a skatepark under the Hamilton Bridge in 2013,[34] and it opened the following year.[35] The city also announced plans for an ice-skating rink in 2014.[36] A citizen-driven restoration movement culminated in a grant from the Bloomberg administration to repair the bridge and make some other improvements. The restored bridge was reopened on June 9, 2015.[37] However, the park itself still faced several problems. A writer for Curbed NY observed that there were homeless encampments under the Harlem River Drive, and that much of the park south of Washington Bridge remained overgrown. In contrast, the NYRP-maintained northern section of the park was extremely clean.[35]

In 2016, about $30 million in funding was allocated for further improvements to the park's recreational facilities as part of the city's Anchor Parks program.[38][39] At the time, NYC Parks postponed plans for an ice-skating rink due to a lack of interest.[36] The first phase of Highbridge Park's renovations started in December 2018. This entailed upgrades to lighting and paths, cleanup of a 10-block section of the park, restoration of the "Grand Staircase", creation of a "welcome garden" at Dyckman Street, and creation of an ADA-accessible entrance plaza at 184th Street.[40] The second phase, which started in July 2019, included restoration of the water tower and the Adventure Playground at 164th Street.[41]

Attractions and facilities

Playgrounds

There are six playgrounds in Highbridge Park:[42]

- Adventure Playground, located at the intersection of 164th Street and Edgecombe Avenue. It was created in 1973, emulating the concept of adventure playgrounds in Europe, and was renovated again in 1989 and 2017.[43]

- CPF Playground, located at 173rd Street near the pool

- Fort George Playground, located at the intersection of Fort George Avenue and St. Nicholas Avenue. It was named after Fort George and was formerly the site of Fort George Amusement Park before it was destroyed in 1914. The playground was acquired by NYC Parks in 1928 and restored in 1999.[44]

- Quisqueya Playground, located at the intersection of 180th Street and Amsterdam Avenue. The name "Quisqueya", honoring the local Dominican community, means "cradle of life" which was a native name for Hispaniola. The playground was created in 1934 and restored in 1998.[45]

- Sunken Playground, located at the intersection of 167th Street and Edgecombe Avenue

- Wallenberg Playground, located at the intersection of 189th Street and Amsterdam Avenue

High Bridge Water Tower

The High Bridge Water Tower, located in the park between West 173rd and 174th Streets, was built in 1866–1872 to help meet the increasing demands on the city's water system. The 200-foot-tall octagonal tower was designed by John B. Jervis in a mixture of Romanesque Revival and neo-Grec styles, and was accompanied by a 7-acre reservoir. The High Bridge system was inaugurated in 1872, and reached its full capacity by 1875.[25] With the opening of the Croton Aqueduct, the High Bridge system became less relied upon; during World War I it was taken out of service when sabotage was feared.[25] In 1949 the tower was disconnected from the system,[25][46] and a carillon, donated by the Altman Foundation, was installed in 1958.[25] The tower's cupola was damaged by an arson fire in 1984. The tower and cupola were rehabilitated and restored in 1989–1990.[25]

Highbridge Play Center

The Highbridge Play Center, located on Amsterdam Avenue between West 172nd and West 174th Streets, was built in 1934-36 in the Art Moderne style, during the Fiorello LaGuardia administration. The supervising architect was Aymar Embury II, and the landscape architect was Gilmore D. Clarke, among others. It was built on the site of the reservoir which had formerly served the High Bridge Water Tower, and features a swimming pool.[46][47]

Bathhouse

The bathhouse is set on an ashlar base above the surrounding street level, while the rest of the structure is made of brick. The building is rectangular: the longer side is located on a north-south axis (i.e. parallel to Amsterdam Avenue), while the shorter side is located on a west-east axis (i.e. parallel to 173rd Street). Its main entrance is located on an elevated, slightly projecting portico at Amsterdam Avenue and 173rd Street. Stone staircases on either side ascend to the portico. The portico itself consists of two brick towers with flagpoles, two concrete piers that carry a concrete architrave, and a bronze sign with the words highbridge play center at the top of the architrave.[48] Just inside the portico, there is a circular turret with a second-story loft, overlooking the first-floor entrance.[48]

The north and south wings respectively contain the women's and men's locker rooms and are nearly identical. Both have nine windows separated by eight brick pilasters. The stone capitals of the pilasters line up with the lintels of the windows. Ramps lead from the extreme ends of each wing. The ground slopes down northward, so that the northern wing is at a higher elevation above the ground than the southern wing.[48] The eastern facade is similar to the western facade, except that it contains entrances to both genders' respective locker rooms, as well as a bronze clock hanging from the architrave. A cellar is located below the northern wing.[49]

Pools

The pool area consists of a rectangular main pool measuring 165 by 228 feet (50 by 69 m) to the east, and a rectangular wading pool measuring 97 by 228 feet (30 by 69 m) to the west. The pool areas are located beside each other, with the 228-foot side being located on the north-south axis. A 29-foot-wide (8.8 m) promenade surrounds the pool area on the north, south, and east sides. A set of concrete bleachers is located to the north of the pool area. A short brick wall encloses the pool area, and niches along the eastern boundary provide another seating area. Just east of the pool area is a set of stairs that leads to the High Bridge. The water tower is located at the northeast corner of the pool area.[50]

Landmark designations

The High Bridge Water Tower was designated a New York City landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1967.[46] The Play Center was designated a New York City landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2007.[46]

References

Notes

- "Highbridge Park". New York Restoration Project. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- Nathan Kensinger (June 25, 2015). "As High Bridge Reopens, a Neglected Park Remains in Its Shadow". Curbed New York. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- "Highbridge Park". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- Hellman, Peter (May 28, 1999). "Bette Midler Was Here: A Park Gets a Second Act". The New York Times. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- Martens, Victoria (August 1, 2019). "Fort George Amusement Park". Museum of the City of New York. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- "The Accurate Database of U.S. National Champions". therealxc.com. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- "Landslide Threatens Highbridge Park" (PDF). The New York Times. April 2, 1922. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- Highbridge Play Center Exterior 2007, pp. 4–5.

- Rodgers, Cleveland (1952). Robert Moses: Builder for Democracy. Holt.

- Caro, Robert (1974). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-48076-3. OCLC 834874.

- "City to Construct 9 Pools To Provide Safe Swimming". New York Daily News. July 23, 1934. p. 8. Retrieved August 18, 2019 – via newspapers.com

- "23 BATHING POOLS PLANNED BY MOSES; Nine to Be Begun in a Month to Meet Shortage of Facilities Caused by Pollution. MANHATTAN TO GET SIX Three of Them Will Be Ready Next Year -- Two of Brooklyn's Six to Be Built Soon". The New York Times. July 23, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- Highbridge Play Center Exterior 2007, p. 6.

- "Moses to Get Two Unneeded Reservoirs As Sites for Stadium and Swimming Pool". The New York Times. April 5, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- "POOL OPENS TOMORROW; La Guardia and Moses to Speak at Highbridge Ceremony". The New York Times. July 13, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- Highbridge Play Center Exterior 2007, p. 7.

- Williams, Timothy (July 6, 2005). "Parks Even the Parks Dept. Won't Claim". The New York Times. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- Highbridge Play Center Exterior 2007, p. 8.

- "History of The High Bridge". NYC Dept. of Parks & Recreation. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- Highbridge Play Center Exterior 2007, p. 10.

- Carmody, Deirdre (March 15, 1981). "Parks Department to Start Hiring for First Time Since Fiscal Crisis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- Carmody, Deirdre (June 25, 1982). "City to Start Repairing Three of Its Swimming Pools". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 121985503.

- Highbridge Play Center Exterior 2007, p. 9.

- Highbridge Play Center Exterior 2007, p. 11.

- Gray, Chrisopher. "Streetscapes: The High Bridge Water Tower; Fire-Damaged Landmark To Get $900,000 Repairs". The New York Times (October 9, 1988)

- "Donation Will Keep 32 Public Pools Open". The New York Times. May 16, 1991. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- Marriott, Michel (July 7, 1993). "A Menacing Ritual Is Called Common in New York Pools". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- "Deep at City Pool; Sex harass is pervasive". New York Daily News. July 11, 1994. p. 7. Retrieved August 9, 2019 – via newspapers.com

- Hellman, Peter (May 28, 1999). "Bette Midler Was Here: A Park Gets a Second Act". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- "Highbridge Park Projects" (PDF). NYC Dept. of Parks & Recreation. February 11, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- Chung, Jen (May 15, 2007). "Highbridge Trails, NYC's First Mountain Bike Trail". Gothamist. Archived from the original on June 12, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- "The Daily Plant : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- "Highbridge Park". New York Restoration Project. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- Barron, Laignee (June 19, 2013). "Washington Heights to get biggest skateboard park in the entire city". nydailynews.com. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- Kensinger, Nathan (June 25, 2015). "As High Bridge Reopens, a Neglected Park Remains in Its Shadow". Curbed NY. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- Pichardo, Carolina (April 29, 2016). "Highbridge Park Ice Rink Plan Dropped After No One Wanted to Run it". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- "High Bridge reopens to bikes, pedestrians" Archived 2015-07-28 at the Wayback Machine MyFox TV

- Neuman, William (August 18, 2016). "5 Neglected New York City Parks to Get $150 Million for Upgrades". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- Krisel, Brendan (August 18, 2016). "City to Invest in Highbridge Park". Washington Heights Media. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- Krisel, Brendan (December 20, 2018). "City Breaks Ground On $30M Highbridge Park Renovation Project". Washington Heights-Inwood, NY Patch. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- Krisel, Brendan (July 15, 2019). "Work Begins On Second Phase Of $30M Highbridge Park Renovation". Washington Heights-Inwood, NY Patch. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- "Highbridge Park Playgrounds : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. June 26, 1939. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- "Highbridge Park Highlights - Adventure Playground : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. June 26, 1939. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- "Highbridge Park Highlights - Fort George Playground : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. June 26, 1939. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- "Highbridge Park Highlights - Quisqueya Playground : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. June 26, 1939. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 566. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- Highbridge Play Center Exterior 2007, p. 10.

- Highbridge Play Center Exterior 2007, p. 11.

- Highbridge Play Center Exterior 2007, p. 11.

Further reading

- Noonan, Theresa C. (June 26, 2007). "Highbridge Play Center Exterior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |