Green ticket roundup

The green ticket roundup (or green card roundup; French: rafle du billet vert) is the name given to the summons and arrest of foreign Jews in France by French police on 14 May 1941.

Although called by this name, it was not actually a "roundup" since the summons were mailed, and those who responded reported to an assembly point on their own. Those who appeared as ordered were arrested, and deported to one of two transit camps in France. From there, the great majority were shipped to Auschwitz where they were killed.

Terminology

This event is called la rafle du billet vert in French.[1][2][3] Scholarship in English has tended to use one of three terms for this topic: either green ticket roundup,[4][5] green card roundup,[6] or the original French term la rafle du billet vert [4] to discuss the event. Green is part of the name in all sources, which report that the summons that was sent to foreign Jewish residents of the Paris region was printed on green paper[5] or green card stock. The word billet can be translated in various ways, in this context, usually "ticket" or "card".

| Look up roundup in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The event is known as a "roundup" both in French (rafle) and in English, although the term roundup is not strictly accurate, since the victims responded to a mailed summons. However, it has become the conventional term to use for this event, because it was the first of a wave of massive arrests of Jews under the Vichy regime, of which the remaining ones were mostly roundups. In particular, it occurred before the larger Vel' d'Hiv Roundup of July 1942.[5][7]

Background

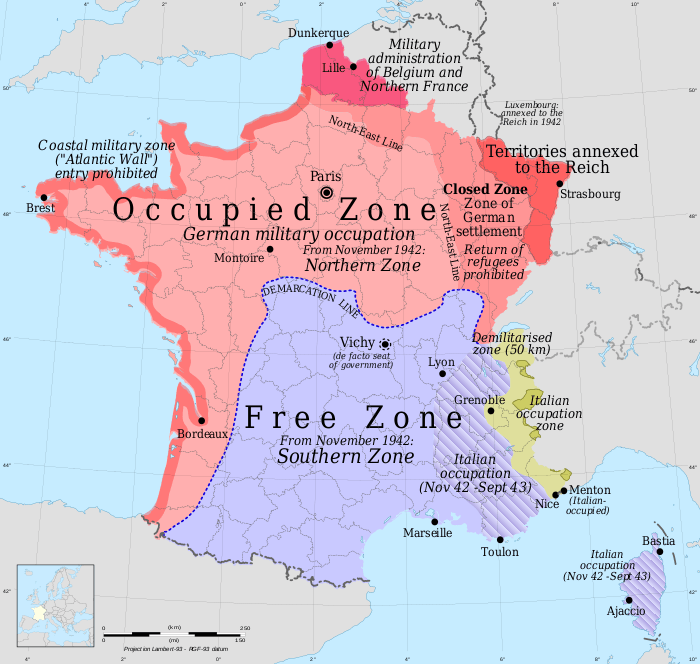

France fell in World War II to the German invasion which began in May 1940 and ended with the occupation of Paris on June 14 and capitulation to Germany eight days later. France was occupied by Nazi Germany and divided in two, with the north and west (including Paris) belonging to the Occupied zone administered directly by Germany, and the rest to the so-called Zone libre ("Free zone") in the south and east. The French government under Marshall Philippe Pétain moved to the town of Vichy in the Zone libre. On July 10, parliament dissolved itself, ending the Third Republic and creating the "French State" (État français; more commonly known as the "Vichy regime") in its place with Petain holding supreme power.

Starting in 1940, the Vichy government voluntarily adopted, without coercion from the German forces, laws that excluded Jews and their children from certain roles in society. According to Marshal Philippe Pétain's chief of staff, "Germany was not at the origin of the anti-Jewish legislation of Vichy. That legislation was spontaneous and autonomous."[8]

Rudolph Schleier, the German Consul General in Paris wrote in a report to Berlin, "The French government has undertaken to send all foreign-born Jews to concentration camps in the Unoccupied Zone," and continued that "[Jews] will be arrested in the Occupied Zone the moment the necessary camps are ready."[9] By 1941, the camps at Pithiviers, Beaune-la-Roland, Compiegne, and Drancy were in operation, chiefly for the purpose of interning foreign Jews from Paris.[10]

In July 1940, Vichy set up a special commission charged with reviewing naturalisations granted since the 1927 reform of the nationality law. Between June 1940 and August 1944, 15,000 persons, mostly Jews, were denaturalised.[11] This bureaucratic decision was instrumental in their subsequent internment.

In September 1940, French authorities performed a census of foreign Jews by order of the Germans. In October, the Vichy regime then took the initiative to promulgate a new law on the status of Jews. Theodor Dannecker, representative of Adolf Eichmann in Paris, wished to speed up the exclusion of Jews, not only by registering them and plundering their goods, but also by interning them. He counted on Carltheo Zeitschel at the German embassy in Paris, who shared the same objectives, and who was in charge of relations with the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs, which was created on 29 March 1941.

On 22 April 1941, Dannecker informed Prefect Ingrand, representative of the Ministry of the Interior in the Occupied zone, of the transformation of the prison camp of Pithiviers into an internment camp, with the transfer of its management to French authorities. At the same time, the Germans insisted on implementation of the 4 October 1940 law which allowed the internment of foreign Jews. The camp at Pithiviers being insufficient for the purpose on its own, the Beaune-la-Rolande internment camp was needed as well, for a total capacity of 5,000 detainees.[12]

Operations

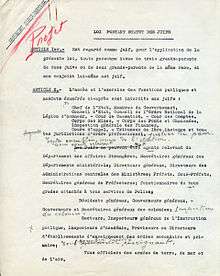

On the basis of censuses, 6694 foreign Jews, mostly Polish males between 18 and 60 years old living in the Paris region, received a summons on a green card (the French: billet vert) hand-delivered by a French policemean for a "status review" (French: examen de situation, lit. 'examination of situation'".[13] The green cards ordered them to go to Parisian police stations[14] on 14 May 1941, accompanied by a relative. The card read:[13]

Mr. _______ is invited to present himself in person, accompanied by one member of his family or by one friend, at 7:00 in the morning on May 14, 1941, for an examination of his situation. He is asked to provide identification. Those who do not present themselves on the set day and hour are liable for the most severe sanctions.

More than half (3747) obeyed the summons,[14] because they thought it was only an administrative formality, and were immediately arrested; while the person accompanying them was requested to go fetch their belongings and food. They were transferred by bus to the Paris Austerlitz railway station and deported the same day by four special trains to the internment camps of the Loiret department, about 1700 in Pithiviers and 2000 in Beaune-la-Rolande.[14]

Fate of the deportees

Between May 1941 and June 1942, about 800 prisoners managed to escape but they were often recaptured. The overwhelming majority of the victims of the operation were deported in the first deportation convoys of June and July 1942 and murdered at Auschwitz concentration camp.

See also

References

Notes

- Cercleshoah 2011.

- Tillier 2011, p. 53.

- Wieviorka 1999, p. 36.

- Laub 2010, p. 217.

- Marrus & Paxton 2019, p. 274.

- Zuccotti 1999, p. 312.

- Drake 2015, p. 207 Unlike the earlier 'green card roundup' this one included a thousand Jews who were French, of whom about forty were well-known lawyers.

- Henri du Moulin de la Barthète. October 26, 1946 cited in Cirtis, Verdict on Vichy. p.111. Quoting from: Robert Satloff (2006): Among the Righteous. p.31

- Grynberg 1991, p. 135, as quoted in Rosenberg 2018, p. 297

- Rosenberg 2018, p. 297.

- François Masure, "État et identité nationale. Un rapport ambigu à propos des naturalisés", in Journal des anthropologues, hors-série 2007, pp. 39–49 (see p. 48) (in French)

- Peschanski 2002.

- Diamant 1977, p. 22, as quoted in Zuccotti 1999, p. 146–147

- Diamant 1977, as quoted in Rosenberg 2018, p. 297

Sources

- "La rafle du billet vert et l'ouverture des camps du Loiret 1941" [The green ticket roundup and the opening of the Loiret camps 1941]. Cercle d’étude de la Déportation et de la Shoah (in French). 5 May 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Diamant, David (1977). Le billet vert: la vie et la résistance à Pithiviers et Beaune-la-Rolande, camps pour juifs, camps pour chrétiens, camps pour patriotes [The green ticket: life and resistance in Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande, camps for Jews, camps for Christians, camps for patriots] (in French). Éditions Renouveau. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Drake, David (16 November 2015), Paris at War: 1939-1944, Boston: Harvard University Press, p. 544, ISBN 978-0-674-49591-3, retrieved 25 May 2020

- Grynberg, Anne (1991). Les camps de la honte: les internés juifs des camps français, 1939-1944 [Camps of shame: Jewish internees in the French camps, 1939-1944]. Textes à l'appui (in French). Paris: La Découverte. p. 135. ISBN 978-2-7071-2030-4. OCLC 878985416.

- Klarsfeld, Serge (1983). Vichy-Auschwitz: le rôle de Vichy dans la solution finale de la question juive en France [Vichy-Auschwitz: the role of Vichy in the final solution of the Jewish question in France] (in French). Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-01573-6. OCLC 13304110.</ref>

- Laub, Thomas J. (2010). After the Fall: German Policy in Occupied France, 1940-1944. Oxford: OUP. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-19-953932-1. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Marrus, Michael R.; Paxton, Robert O. (17 September 2019) [1st pub. Basic Books (1981)], Vichy France and the Jews (2nd ed.), Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-1-5036-0982-2, OCLC 1137492753, retrieved 25 May 2020

- Peschanski, Denis (2002). La France des camps. L'internement 1938-1946 [France in the era of the camps. The internment 1938–1946] (doctoral thesis). Suite des temps (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-214077-8. OCLC 937884093.

- Rosenberg, Pnina (10 September 2018). "Yiddish Theatre in the camps of the Occupied Zone". In Dalinger, Brigitte; Zangl, Veronika (eds.). Theater unter NS-Herrschaft: Theatre under Pressure [Theatre under NS rule: Theatre under Pressure]. Theater - Film - Medien (Print) #2. Göttingen: V&R Unipress. p. 297. ISBN 978-3-8470-0642-8. OCLC 1135506612. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Tillier, Alice (2011). Les 100 dates les plus marquantes de la seconde guerre mondiale [The 100 most important dates of the Second World War] (in French). Editions Asap. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-2-35932-052-7. OCLC 762677546. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Wieviorka, Annette (1999). La Shoah: témoignage savoirs, oeuvres ; cet ouvrage fait suite aux journees detude organisees a Orleans les 14, 15 et 16 novembre 1996 par le Cercil avec les Universites de Paris VII et d'Orleans [The Holocaust: Testimony, Knowledge, Works; this book is a follow-up to the workshops organized in Orleans on 14, 15 and 16 November 1996 by Cercil along with the Universities of Paris VII and Orleans.] (in French). Cercil ; Press Universitaires de Vincennes. ISBN 978-2-9507561-4-5. OCLC 313238488. Retrieved 27 May 2020.</ref>

- Zuccotti, Susan (1999), "5 Roundups and Deportations", The Holocaust, the French, and the Jews, Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska Press, p. 81, ISBN 0-8032-9914-1, retrieved 25 May 2020

Further reading

- "Le rôle des camps de Pithiviers et de Beaune-la-Rolande dans l'internement et la déportation des Juifs de France" [The role of Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande camps in the internment and deportation of the Jews of France] (PDF). Cercil archive (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- Verny, Benoît; Burko-Falcman, Berthe; Ungar, Claude (2011). "La « rafle » du billet vert et l'ouverture des camps d'internement du Loiret" [The green ticket roundup and the opening of internment camps in the Loiret] (in French). conférence du Cercle d'étude.

- Josephs, Jeremy (1 May 2012), Swastika Over Paris, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, p. 60, ISBN 978-1-4088-3448-0, retrieved 25 May 2020