Gott mit uns

Gott mit uns ("God with us") is a phrase commonly used in heraldry in Prussia (from 1701) and later by the German military during the periods spanning the German Empire (1871 to 1918), the Third Reich (1933 to 1945), and the early years of West Germany (1949 to 1962). It was also commonly used by Sweden in most of its wars and especially as a warcry during the Thirty Years' War.

Origins

Matthew 1:23, refers to the prophecy written in Isaiah 7:14, glossing the name Immanuel (Emmanuel, עִמָּנוּאֵל) as "God with us":

Ancient Greek: ἰδοὺ ἡ παρθένος ἐν γαστρὶ ἔξει καὶ τέξεται υἱόν, καὶ καλέσουσι τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ Εμμανουήλ, ὅ ἐστι μεθερμηνευόμενον μεθ᾽ ἡμῶν ὁ θεός.

Behold, a virgin shall be with child, and shall bring forth a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel, which being interpreted is, God with us.

German: "Siehe, eine Jungfrau wird schwanger sein und einen Sohn gebären, und sie werden seinen Namen Immanuel heißen", das ist verdolmetscht: Gott mit uns.

Usage

Roman Empire

Nobiscum Deus in Latin, Μεθ᾽ἡμων ὁ Θεός (Meth hēmon ho theos) in Greek, was a battle cry of the late Roman Empire and of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Russia / Ukraine

It is also a popular hymn of the Eastern Orthodox Church, sung during the service of Great Compline (Μεγα Αποδειπνον). The Church Slavonic translation is Съ Hами Богъ (S Nami Bog). "Съ нами Богъ!" S nami Bog! was used as a motto by the Russian Empire. During the War in Donbass, a Ukrainian version (З нами Бог, Z nami Bog) was used by the Aidar Battalion. There is also popular russian song ″Мы Русские...С нами Бог!!!″, which has the same meaning.[1]

Germany

It was used for the first time in Germany by the Teutonic Order.[2]

In the 17th century, the phrase Gott mit uns was used as a 'field word', a means of recognition akin to a password,[3] by the army of Gustavus Adolphus at the battles of Breitenfeld (1631), Lützen (1632) and Wittstock (1636) in the Thirty Years' War.[4]

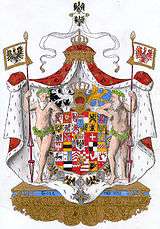

In 1701, Frederick I of Prussia changed his coat of arms as Prince-Elector of Brandenburg. The electoral scepter had its own shield under the electoral cap. Below, the motto Gott mit uns appeared on the pedestal. The Prussian Order of the Crown was Prussia's lowest ranking order of chivalry, and was instituted in 1861. The obverse gilt central disc bore the crown of Prussia, surrounded by a blue enamel ring bearing the motto of the German Empire Gott Mit Uns.

At the time of the completion of German unification in 1871, the imperial standard bore the motto Gott mit uns on the arms of an Iron Cross.[5] Imperial German 3 and 5 mark silver and 20 mark gold coins had Gott mit uns inscribed on their edge.

German soldiers had Gott mit uns inscribed on their helmets in the First World War.[6] The slogan entered the mindset on both sides; in 1916 a cartoon was printed in the New York Tribune captioned "Gott Mit Uns!", showing "a German officer in spiked helmet holding a smoking revolver as he stood over the bleeding form of a nurse. It symbolized the rising popular demand that the United States shed its neutrality".[7]

In June 1920 George Grosz produced a lithographic collection in three editions entitled Gott mit uns. A satire on German society and the counterrevolution, the collection was swiftly banned. Grosz was charged with insulting the army, which resulted in a 300 German Mark fine and the destruction of the collection.[8]

During the Second World War Wehrmacht soldiers wore this slogan on their belt buckles,[9] as opposed to members of the Waffen SS, who wore the motto Meine Ehre heißt Treue ('My honour is loyalty').[10] After the war the motto was also used by the Bundeswehr and German police. It was replaced with "Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit" ("Unity and Justice and Freedom") in 1962 (police within the 1970s), the first line of the third stanza of the German national anthem.

Gallery

Coat of arms of Frederick I of Prussia

Coat of arms of Frederick I of Prussia

German arms of 1871 (note banners)

German arms of 1871 (note banners) Coat of arms of the State of Prussia (1933-1935)

Coat of arms of the State of Prussia (1933-1935)- A First World War-era Prussian enlisted man's belt buckle

See also

References

- Youtube Youtube

- Haldon, John (1999). Warfare, State and Society in the Byzantine World. Taylor & Francis, Inc. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-85728-495-9.

- Young, Alan R., ed. (1995). The English Emblem Tradition: Volume 3: Emblematic Flag Devices of the English Civil Wars, 1642-1660 Index Emblematicus. University of Toronto Press. p. xxiv.

- Brzezinski, Richard (1993). The Army of Gustavus Adolphus (2): Cavalry (Men-at-Arms). Osprey Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 1-85532-350-8.

- Preble, George Henry, History of the Flag of the United States of America: With a Chronicle of the Symbols, Standards, Banners, and Flags of Ancient and Modern Nations, 2nd ed, p. 102; A. Williams and co, 1880

- Spector, Robert Melvyn (2004). World Without Civilization: Mass Murder and the Holocaust, History, and Analysis. University Press of America. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7618-2963-8.

- Hoehling, Adolph A.; The Great War at Sea: A History of Naval Action, 1914-18, p. 106; Crowell, 1965; ISBN 1-56619-726-0

- Crockett, Dennis (1999). German Post-Expressionism: The Art of the Great Disorder, 1918-1924. Penn State University Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-271-01796-9.

- Armbrüster, Thomas (2005). Management and Organization in Germany. Ashgate Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-7546-3880-3.

- McConnell, Winder (1998). A Companion to the Nibelungenlied. Boydell & Brewer. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-57113-151-5.

External links

- "Gott Mit Uns." Time Magazine archive article. Monday September 18, 1944.