Reichswehr

The Reichswehr (English: Realm Defence) formed the military organisation of Germany from 1919 until 1935, when it was united with the new Wehrmacht (Defence Force).

| Realm Defence | |

|---|---|

| Reichswehr | |

.svg.png) War ensign of the Reichswehr | |

| Founded | 19 January 1919 |

| Disbanded | 16 March 1935 |

| Service branches |

|

| Headquarters | Zossen, Brandenburg |

| Leadership | |

| Commander-in-chief | Friedrich Ebert (1919–25) Paul von Hindenburg (1925–34) Adolf Hitler (1934–35) |

| Minister of Defence | See list |

| Chief of the Troop Office | See list |

| Manpower | |

| Military age | 18–45 |

| Conscription | No |

| Active personnel | 115,000 (1921) |

| Related articles | |

| History | German Revolution Silesian Uprisings Suppression of the Beer Hall Putsch Ruhr Uprising Kapp Putsch (limited support) |

| Ranks | Military ranks of the Weimar Republic |

Founding

At the end of World War I, the forces of the German Empire were disbanded, the men returning home individually or in small groups. Many of them joined the Freikorps (Free Corps), a collection of volunteer paramilitary units that were involved in suppressing the German Revolution and border clashes between 1918 and 1923.

The Reichswehr was limited to a standing army of 100,000 men,[1] and a navy of 15,000. The establishment of a general staff was prohibited. Heavy weapons such as artillery above the calibre of 105 mm (for naval guns, above 205 mm), armoured vehicles, submarines and capital ships were forbidden, as were aircraft of any kind. Compliance with these restrictions was monitored until 1927 by the Military Inter-Allied Commission of Control.

It was conceded that the newly formed Weimar Republic did need a military, so on 6 March 1919 a decree established the Vorläufige Reichswehr (Provisional National Defence), consisting of the Vorläufiges Reichsheer (Provisional National Army) and Vorläufige Reichsmarine (Provisional National Navy). The Vorläufige Reichswehr was made up of 43 brigades.[2]

On 30 September 1919, the army was reorganised as the Übergangsheer (Transitional Army), and the force size was reduced to 20 brigades.[2] About 400,000 men were left in the armed forces,[3] and in May 1920 it further was downsized to 200,000 men and restructured again, forming three cavalry divisions and seven infantry divisions. On 1 October 1920 the brigades were replaced by regiments and the manpower was now only 100,000 men as stipulated by the Treaty of Versailles.[2] This lasted until 1 January 1921, when the Reichswehr was officially established according to the limitations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles (Articles 159 to 213).

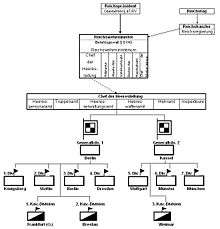

The Reichswehr was a unified organisation composed of the following (as was allowed by the Versailles Treaty):

- The Reichsheer, an army consisted of:

- seven infantry divisions, and

- three cavalry divisions.[4]

- General Command 1 at Berlin supervised 1st Division (Königsberg), 2nd Division (Stettin), 3rd Division (Berlin), and 4th Division (Dresden) as well as 1st and 2nd Cavalry Divisions (Frankfurt an der Oder and Breslau).

- General Command 2 at Kassel supervised 5, 6, 7 and 3rd Cavalry divisions (Stuttgart, Münster, Munich, and Weimar).

- The Reichsmarine, a navy with a limited number of certain types of ships and boats. No submarines were allowed.[5]

Despite the limitations on its size, their analysis of the loss of World War I, research and development, secret testing abroad (in co-operation with the Red Army) and planning for better times went on. In addition, although forbidden to have a General Staff, the army continued to conduct the typical functions of a general staff under the disguised name of Truppenamt (Troop Office). During this time, many of the future leaders of the Wehrmacht – such as Heinz Guderian – first formulated the ideas that they were to use so effectively a few years later.

State within the state

In 1918, Wilhelm Groener, Quartermaster General of the German Army, had assured the government of the military's loyalty.[6][7] But most military leaders refused to accept the democratic Weimar Republic as legitimate and instead the Reichswehr under the leadership of Hans von Seeckt became a state within the state that operated largely outside of the control of the politicians.[8] Reflecting this position as a “state within the state”, the Reichswehr created the Ministeramt or Office of the Ministerial Affairs in 1928 under Kurt von Schleicher to lobby the politicians.[9] The German historian Eberhard Kolb wrote that

…from the mid-1920s onwards the Army leaders had developed and propagated new social conceptions of a militarist kind, tending towards a fusion of the military and civilian sectors and ultimately a totalitarian military state (Wehrstaat).[10]

The biggest influence on the development of the Reichswehr was Hans von Seeckt (1866–1936), who served from 1920 to 1926 as Chef der Heeresleitung (Chief of the Army Command) – succeeding Walther Reinhardt. After the Kapp Putsch, Hans von Seeckt took over this post. After Seeckt was forced to resign in 1926, Wilhelm Heye took the post. Heye was in 1930 succeeded by Kurt Freiherr von Hammerstein-Equord, who submitted his resignation on 27 December 1933.

The forced reduction of strength of the German army from 4,500,000 in 1918 to 100,000 after Treaty of Versailles, enhanced the quality of the Reichsheer because only the best were permitted to join the army. However the changing face of warfare meant that the smaller army was impotent without mechanization and air support, no matter how much effort was put into modernising infantry tactics.

During 1933 and 1934, after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, the Reichswehr began a secret program of expansion. In December 1933, the army staff decided to increase the active strength to 300,000 men in 21 divisions. On 1 April 1934, between 50,000 and 60,000 new recruits entered and were assigned to special training battalions. The original seven infantry divisions of the Reichswehr were expanded to 21 infantry divisions, with Wehrkreis headquarters increased to the size of a corps HQ on 1 October 1934.[11] These divisions used cover names to hide their divisional size, but, during October 1935, these were dropped. Also, during October 1934, the officers who had been forced to retire in 1919 were recalled; those who were no longer fit for combat were assigned to administrative positions – releasing fit officers for front-line duties.[12]

Transition to the Wehrmacht

The National Socialist Party came to power in Germany in 1933. The Sturmabteilung (Storm Battalion or SA), the Nazi Party militia, played a prominent part in this change. Ernst Röhm and his SA colleagues thought of their force – at that time over three million strong – as the future army of Germany, replacing the smaller Reichswehr and its professional officers, whom they viewed as old fogies who lacked revolutionary spirit. Röhm wanted to become Minister of Defense, and in February 1934 demanded that the much smaller Reichswehr be merged into the SA to form a true people's army. This alarmed both political and military leaders, and to forestall the possibility of a coup, Hitler sided with conservative leaders and the military. Röhm and the leadership of the SA were murdered, along with many other political adversaries of the Nazis, including two Reichswehr generals, in the Night of the Long Knives (30 June – 2 July 1934).

The secret programme of expansion by the military finally became public in 1935. On 1 March 1935 the Luftwaffe was established. On 16 March 1935 Germany introduced conscription – in violation of the Treaty of Versailles. In the same act, the German government renamed the Reichswehr as the Wehrmacht (defence force). On 1 June 1935 the Reichsheer was renamed the Heer (Army) and the Reichsmarine the Kriegsmarine.[13]

See also

- Ministry of the Reichswehr

- Weimar paramilitary groups

References

Citations

- Darman, Peter, ed. (2007). "Introduction: Deutschland Erwache". World War II A Day-By-Day History (60th Anniversary ed.). China: The Brown Reference Group plc. p. 10; 575. ISBN 978-0-7607-9475-3.

The Reichswehr, the 100,000-man post-Versailles Treaty German Army, was forced to train with dummy tanks.

- Axis History Factbook, Introduction to the Reichswehr, accessed July 2015.

- Haskew, Michael, The Wehrmacht, Amber Books Ltd. 2011, p. 13

- Haskew, The Wehrmacht, p. 13

- Porter, David, The Kriegsmarine, Amber Books Ltd. 2010, p. 11

- Wheeler-Bennett, J.W. (1967). Hindenburg: The Wooden Titan. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 207–208.

- William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany, New York, NY, Simon & Schuster, 2011, p. 54

- Kolb, Eberhard The Weimar Republic London: Routledge, 2005, p. 172

- Wheeler-Bennett, John The Nemesis of Power, London: Macmillan, 1967, p. 198

- Kolb, Eberhard The Weimar Republic London: Routledge, 2005, p. 173.

- Robert B. Kane, Disobedience and Conspiracy in the German Army 1918–1945, 102. See also Robert J. O'Neill, The German Army and the Nazi Party 1933–39, London, 1968, pp. 91–92.

- Stone, David J. (2006) Fighting for the Fatherland: The Story of the German Soldier from 1648 to the Present Day, p. 450.

- Stone says 21 May; Fighting for the Fatherland, p. 316.

Bibliography

- Deist, Wilhelm; Messerschmidt, Manfred; Volkmann, Hans-Erich; Wette, Wolfram (1990). Volume I The Build-up of German Aggression. Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg [Germany and the Second World War]. I. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt GmbH. ISBN 0-19-822866-X.

- Wheeler-Bennett, Sir John (2005) The Nemesis of Power: German Army in Politics, 1918–1945 New York: Palgrave Macmillan Publishing Company.

- Keller, Peter (2014) "Die Wehrmacht der Deutschen Republik ist die Reichswehr". Die deutsche Armee 1918–1921 Paderborn: Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh.