Geohash

Geohash is a public domain geocode system invented in 2008 by Gustavo Niemeyer[1] and (similar work in 1966) G.M. Morton,[2] which encodes a geographic location into a short string of letters and digits. It is a hierarchical spatial data structure which subdivides space into buckets of grid shape, which is one of the many applications of what is known as a Z-order curve, and generally space-filling curves.

Geohashes offer properties like arbitrary precision and the possibility of gradually removing characters from the end of the code to reduce its size (and gradually lose precision). Geohashing guarantees that the longer a shared prefix between two geohashes is, the spatially closer they are together. The reverse of this is not guaranteed, as two points can be very close but have a short or no shared prefix.

History

The core part of the Geohash algorithm and the first initiative to similar solution was documented in a report of G.M. Morton in 1966, "A Computer Oriented Geodetic Data Base and a New Technique in File Sequencing".[2] The Morton work was used for efficient implementations of Z-order curve, like in this modern (2014) Geohash-integer version, based on direct interleave 64-bits integers. But his geocode proposal was not human-readable and was not popular.

Apparently, in the late 2000s, G. Niemeyer still didn't know about Morton's work, and reinvented it, adding the use of base32 representation. In February 2008, together with the announcement of the system,[1] he launched the website http://geohash.org, which allows users to convert geographic coordinates to short URLs which uniquely identify positions on the Earth, so that referencing them in emails, forums, and websites is more convenient.

Many variations has been developed, as the OpenStreetMap's short link[3] (using base64 instead of base32) in 2009, the 64-bit Geohash[4] in 2014, the exotic Hilbert-Geohash[5][6] in 2016, and others.

Typical and main usages

To obtain the Geohash, the user provides an address to be geocoded, or latitude and longitude coordinates, in a single input box (most commonly used formats for latitude and longitude pairs are accepted), and performs the request.

Besides showing the latitude and longitude corresponding to the given Geohash, users who navigate to a Geohash at geohash.org are also presented with an embedded map, and may download a GPX file, or transfer the waypoint directly to certain GPS receivers. Links are also provided to external sites that may provide further details around the specified location.

For example, the coordinate pair 57.64911,10.40744 (near the tip of the peninsula of Jutland, Denmark) produces a slightly shorter hash of u4pruydqqvj.

The main usages of Geohashes are:

- As a unique identifier.

- To represent point data, e.g. in databases.

Geohashes have also been proposed to be used for geotagging.

When used in a database, the structure of geohashed data has two advantages. First, data indexed by geohash will have all points for a given rectangular area in contiguous slices (the number of slices depends on the precision required and the presence of geohash "fault lines"). This is especially useful in database systems where queries on a single index are much easier or faster than multiple-index queries. Second, this index structure can be used for a quick-and-dirty proximity search: the closest points are often among the closest geohashes.

Technical description

A formal description for Computational and Mathematical views.

Textual representation

For exact latitude and longitude translations Geohash is a spatial index of base 4, because it transforms the continuous latitude and lontitude space coordinates into a hierarchical discrete grid, using a recurrent four-partition of the space. To be a compact code it uses base 32 and represents its values by the following alphabet, that is the "standard textual representation".

| Decimal | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base 32 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | b | c | d | e | f | g | |||

| Decimal | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

| Base 32 | h | j | k | m | n | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z | |||

The "Geohash alphabet" (32ghs) uses all digits 0-9 and almost all lower case letters except "a", "i", "l" and "o".

For example, using the table above and the constant , the Geohash ezs42 can be converted to a decimal representation by ordinary positional notation:

- [

ezs42]32ghs =

- =

- =

- = =

Geometrical representation

The geometry of the Geohash have a mixed spatial representation:

- Geohashes with 2, 4, 6, ... e digits (even digits) are represented by Z-order curve in a "regular grid" where decoded pair (latitude,longitude) has uniform uncertainty, valid as Geo URI.

- Geohashes with 1, 3, 5, ... d digits (odd digits) are represented by "И-order curve". Latitude and longitude of the decoded pair has different uncertainty (longitude is truncated).

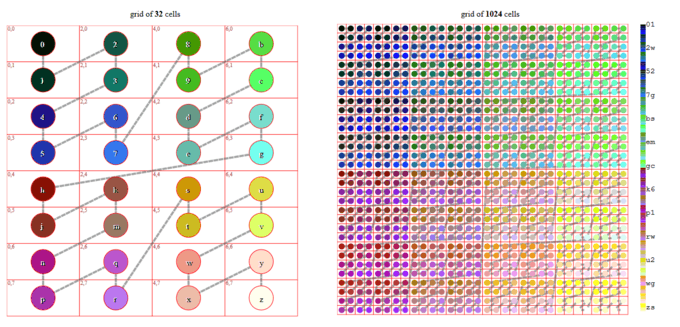

Is possible to build the "И-order curve" from Z-order by merging neighboring cells and indexing the result rectangular grid by the function j=floor(i ÷ 2). The side illustration shows how to obtain the grid of 32 rectangular cells from the grid of 64 square cells.

The most important property of Geohash for humans is that it preserves spatial hierarchy in the code prefixes.

For example, in the "1 Geohash digit grid" illustration of 32 rectangles, above, the spatial region of the code e (rectangle of greyish blue circle at position 4,3) is preserved with prefix e in the "2 digit grid" of 1024 rectangles (scale showing em and greyish green to blue circles at grid).

Algorithm and example

Using the hash ezs42 as an example, here is how it is decoded into a decimal latitude and longitude. The first step is decoding it from textual "base 32ghs", as showed above, to obtain the binary representation:

- .

This operation results in the bits 01101 11111 11000 00100 00010. Assuming that counting starts at 0 in the left side, the even bits are taken for the longitude code (0111110000000), while the odd bits are taken for the latitude code (101111001001).

Each binary code is then used in a series of divisions, considering one bit at a time, again from the left to the right side. For the latitude value, the interval -90 to +90 is divided by 2, producing two intervals: -90 to 0, and 0 to +90. Since the first bit is 1, the higher interval is chosen, and becomes the current interval. The procedure is repeated for all bits in the code. Finally, the latitude value is the center of the resulting interval. Longitudes are processed in an equivalent way, keeping in mind that the initial interval is -180 to +180.

For example, in the latitude code 101111001001, the first bit is 1, so we know our latitude is somewhere between 0 and 90. Without any more bits, we'd guess the latitude was 45, giving us an error of ±45. Since more bits are available, we can continue with the next bit, and each subsequent bit halves this error. This table shows the effect of each bit. At each stage, the relevant half of the range is highlighted in green; a low bit selects the lower range, a high bit selects the upper range.

The column “mean value” shows the latitude, simply the mean value of the range. Each subsequent bit makes this value more precise.

| Latitude code 101111001001 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bit position | bit value | min | mid | max | mean value | maximum error |

| 0 | 1 | -90.000 | 0.000 | 90.000 | 45.000 | 45.000 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 45.000 | 90.000 | 22.500 | 22.500 |

| 2 | 1 | 0.000 | 22.500 | 45.000 | 33.750 | 11.250 |

| 3 | 1 | 22.500 | 33.750 | 45.000 | 39.375 | 5.625 |

| 4 | 1 | 33.750 | 39.375 | 45.000 | 42.188 | 2.813 |

| 5 | 1 | 39.375 | 42.188 | 45.000 | 43.594 | 1.406 |

| 6 | 0 | 42.188 | 43.594 | 45.000 | 42.891 | 0.703 |

| 7 | 0 | 42.188 | 42.891 | 43.594 | 42.539 | 0.352 |

| 8 | 1 | 42.188 | 42.539 | 42.891 | 42.715 | 0.176 |

| 9 | 0 | 42.539 | 42.715 | 42.891 | 42.627 | 0.088 |

| 10 | 0 | 42.539 | 42.627 | 42.715 | 42.583 | 0.044 |

| 11 | 1 | 42.539 | 42.583 | 42.627 | 42.605 | 0.022 |

| Longitude code 0111110000000 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bit position | bit value | min | mid | max | mean value | maximum error |

| 0 | 0 | -180.000 | 0.000 | 180.000 | -90.000 | 90.000 |

| 1 | 1 | -180.000 | -90.000 | 0.000 | -45.000 | 45.000 |

| 2 | 1 | -90.000 | -45.000 | 0.000 | -22.500 | 22.500 |

| 3 | 1 | -45.000 | -22.500 | 0.000 | -11.250 | 11.250 |

| 4 | 1 | -22.500 | -11.250 | 0.000 | -5.625 | 5.625 |

| 5 | 1 | -11.250 | -5.625 | 0.000 | -2.813 | 2.813 |

| 6 | 0 | -5.625 | -2.813 | 0.000 | -4.219 | 1.406 |

| 7 | 0 | -5.625 | -4.219 | -2.813 | -4.922 | 0.703 |

| 8 | 0 | -5.625 | -4.922 | -4.219 | -5.273 | 0.352 |

| 9 | 0 | -5.625 | -5.273 | -4.922 | -5.449 | 0.176 |

| 10 | 0 | -5.625 | -5.449 | -5.273 | -5.537 | 0.088 |

| 11 | 0 | -5.625 | -5.537 | -5.449 | -5.581 | 0.044 |

| 12 | 0 | -5.625 | -5.581 | -5.537 | -5.603 | 0.022 |

(The numbers in the above table have been rounded to 3 decimal places for clarity)

Final rounding should be done carefully in a way that

So while rounding 42.605 to 42.61 or 42.6 is correct, rounding to 43 is not.

Digits and precision in km

| geohash length | lat bits | lng bits | lat error | lng error | km error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ±23 | ±23 | ±2500 |

| 2 | 5 | 5 | ±2.8 | ±5.6 | ±630 |

| 3 | 7 | 8 | ±0.70 | ±0.70 | ±78 |

| 4 | 10 | 10 | ±0.087 | ±0.18 | ±20 |

| 5 | 12 | 13 | ±0.022 | ±0.022 | ±2.4 |

| 6 | 15 | 15 | ±0.0027 | ±0.0055 | ±0.61 |

| 7 | 17 | 18 | ±0.00068 | ±0.00068 | ±0.076 |

| 8 | 20 | 20 | ±0.000085 | ±0.00017 | ±0.019 |

Limitations when used for deciding proximity

Edge cases

Geohashes can be used to find points in proximity to each other based on a common prefix. However, edge case locations close to each other but on opposite sides of the 180 degree meridian will result in Geohash codes with no common prefix (different longitudes for near physical locations). Points close to the North and South poles will have very different geohashes (different longitudes for near physical locations).

Two close locations on either side of the Equator (or Greenwich meridian) will not have a long common prefix since they belong to different 'halves' of the world. Put simply, one location's binary latitude (or longitude) will be 011111... and the other 100000...., so they will not have a common prefix and most bits will be flipped. This can also be seen as a consequence of relying on the Z-order curve (which could more appropriately be called an N-order visit in this case) for ordering the points, as two points close by might be visited at very different times. However, two points with a long common prefix will be close by.

In order to do a proximity search, one could compute the southwest corner (low geohash with low latitude and longitude) and northeast corner (high geohash with high latitude and longitude) of a bounding box and search for geohashes between those two. This search will retrieve all points in the z-order curve between the two corners, which can be far too many points. This method also breaks down at the 180 meridians and the poles. Solr uses a filter list of prefixes, by computing the prefixes of the nearest squares close to the geohash .

Non-linearity

Since a geohash (in this implementation) is based on coordinates of longitude and latitude the distance between two geohashes reflects the distance in latitude/longitude coordinates between two points, which does not translate to actual distance, see Haversine formula.

Example of non-linearity for latitude-longitude system:

- At the Equator (0 Degrees) the length of a degree of longitude is 111.320 km, while a degree of latitude measures 110.574 km, an error of 0.67%.

- At 30 Degrees (Mid Latitudes) the error is 110.852/96.486 = 14.89%

- At 60 Degrees (High Arctic) the error is 111.412/55.800 = 99.67%, reaching infinity at the poles.

Note that these limitations are not due to geohashing, and not due to latitude-longitude coordinates, but due to the difficulty of mapping coordinates on a sphere (non linear and with wrapping of values, similar to modulo arithmetic) to two dimensional coordinates and the difficulty of exploring a two dimensional space uniformly. The first is related to Geographical coordinate system and Map projection, and the other to Hilbert curve and z-order curve. Once a coordinate system is found that represents points linearly in distance and wraps up at the edges, and can be explored uniformly, applying geohashing to those coordinates will not suffer from the limitations above.

While it is possible to apply geohashing to an area with a Cartesian coordinate system, it would then only apply to the area where the coordinate system applies.

Despite those issues, there are possible workarounds, and the algorithm has been successfully used in Elasticsearch,[7] MongoDB,[8] HBase, Redis,[9] and Accumulo[10] to implement proximity searches.

Similar indexing systems

An alternative to storing Geohashes as strings in a database are Locational codes, which are also called spatial keys and similar to QuadTiles.[11][12]

In some geographical information systems and Big Data spatial databases, a Hilbert curve based indexation can be used as an alternative to Z-order curve, like in the S2 Geometry library.[13]

In 2019 a front-end was designed by QA Locate[14] in what they called GeohashPhrase[15] to use phrases to code Geohashes for easier communication via spoken English language. There were plans to make GeohashPhrase open source.[16]

- Open Location Code (2014, aka. "plus codes", Google Maps)

- 3Geonames (2018, open source)

- GeoKey (2018, proprietary)

- Ghana Post GPS (2017)

- Xaddress

- Maidenhead Locator System (1980)

- Makaney Code (2011)

- MapCode (2008)

- Military Grid Reference System

- Natural Area Code

- QRA locator (1959)

- Universal Transverse Mercator coordinate system

- what3words (2013, proprietary)

- WhatFreeWords

- GEOREF (similar 2-digit hierarchy code)

Licensing

The Geohash algorithm was put in the public domain by its inventor in a public announcement on February 26, 2008.[17]

While comparable algorithms have been successfully patented[18] and had copyright claimed upon,[19][20] GeoHash is based on an entirely different algorithm and approach.

See also

- List of geodesic-geocoding systems

- Geohash-36 (is not a Geohash-variant)

- Grid (spatial index)

- Maidenhead Locator System

- Military Grid Reference System

- Morton number (number theory)

- Natural Area Code

- Numbering scheme

- Open Location Code (plus code)

- space-filling curves

- what3words

- Z-order curve

References

- Evidences at the Wayback Machine (also with 2008's records of this article):

- G. M. Morton (1966)"A Computer Oriented Geodetic Data Base and a New Technique in File Sequencing". Report in IBM Canada.

- The OpenStreetMap's short link, documented in wiki.openstreetmap.org, was released in 2009, is near the same source-code 10 years after. It is strongly based on Morton's interlace algorithm.

- The "Geohash binary 64 bits" have classic solutions, as yinqiwen/geohash-int, and optimized solutions, as mmcloughlin/geohash-assembly.

- Tibor Vukovic (2016), "Hilbert-Geohash - Hashing Geographical Point Data Using the Hilbert Space-Filling Curve". https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d23c/996f44b1443fca76276ce8d37239fb8fd6f9.pdf

- https://github.com/tammoippen/geohash-hilbert

- geo_shape Datatype in Elasticsearch

- Geospatial Indexing in MongoDB

- Spatio-temporal Indexing in Non-relational Distributed Databases

- Spatial Keys

- QuadTiles

- "S2 Geometry Library" for optimized spatial indexation, https://s2geometry.io

- "QA Locate | The Power of Precision Location Intelligence". QA Locate. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- "GeohashPhrase™". QA Locate. 2019-09-17. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- thelittlenag (2019-11-11). "At QA Locate we've been working on a solution that we call GeohashPhrase | Hacker News". news.ycombinator.com. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- geohash.org announcement post in groundspeak.com forum

- Compact text encoding of latitude/longitude coordinates - Patent 20050023524

- Does Microsoft Infringe the Natural Area Coding System? Archived 2010-12-28 at the Wayback Machine

- The Natural Area Coding System - Legal and Licensing