Gattaca

Gattaca is a 1997 American science fiction film written and directed by Andrew Niccol. It stars Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman, with Jude Law, Loren Dean, Ernest Borgnine, Gore Vidal, and Alan Arkin appearing in supporting roles.[4] The film presents a biopunk vision of a future society driven by eugenics where potential children are conceived through genetic selection to ensure they possess the best hereditary traits of their parents.[5] The film centers on Vincent Freeman, played by Hawke, who was conceived outside the eugenics program and struggles to overcome genetic discrimination to realize his dream of going into space.

| Gattaca | |

|---|---|

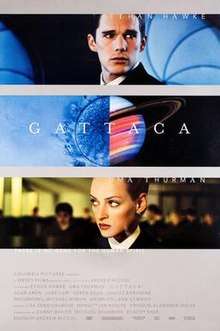

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Andrew Niccol |

| Produced by | |

| Written by | Andrew Niccol |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Michael Nyman |

| Cinematography | Sławomir Idziak |

| Edited by | Lisa Zeno Churgin |

Production company | Jersey Films |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 106 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $36 million[2] |

| Box office | $12.5 million[3] |

The film draws on concerns over reproductive technologies that facilitate eugenics, and the possible consequences of such technological developments for society. It also explores the idea of destiny and the ways in which it can and does govern lives. Characters in Gattaca continually battle both with society and with themselves to find their place in the world and who they are destined to be according to their genes.

The film's title is based on the letters G, A, T, and C, which stand for guanine, adenine, thymine, and cytosine, the four nucleobases of DNA.[6] It was a 1997 nominee for the Academy Award for Best Art Direction and the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score.

Plot

In the future, eugenics is common. A genetic registry database uses biometrics to classify those so created as "valids" while those conceived by traditional means and more susceptible to genetic disorders are known as "in-valids". Genetic discrimination is illegal, but in practice genotype profiling is used to identify valids to qualify for professional employment while in-valids are relegated to menial jobs.

Vincent Freeman is conceived without the aid of genetic selection; his genetic profile indicates a high probability of several disorders and an estimated lifespan of 30.2 years. His parents, regretting their decision, use genetic selection in conceiving their next child, Anton. Growing up, the two brothers often play a game of "chicken" by swimming out to sea as far as they can, with the first one returning to shore considered the loser. Vincent always loses. Vincent dreams of a career in space travel but is always reminded of his genetic inferiority. One day, Vincent challenges Anton to a game of chicken and beats him. Anton starts to drown and is saved by Vincent. Shortly after, Vincent leaves home.

Years later, Vincent works as an in-valid, cleaning office spaces including that of Gattaca Aerospace Corporation, a spaceflight conglomerate. He gets a chance to pose as a valid by using hair, skin, blood and urine samples from a donor, Jerome Eugene Morrow, a former swimming star who was paralyzed after being hit by a car. With Jerome's genetic makeup, Vincent gains employment at Gattaca, and is assigned to be navigator for an upcoming trip to Saturn's moon Titan. To keep his identity hidden, Vincent must meticulously groom and scrub down daily to remove his own genetic material and pass daily DNA scanning and urine tests using Jerome's samples.

Gattaca becomes embroiled in controversy when one of its administrators is murdered a week before the flight. The police find a fallen eyelash of Vincent's at the scene. An investigation is launched to find the owner of the eyelash, considering them the top suspect. During this, Vincent becomes close to a co-worker, Irene Cassini, and falls in love with her. Though a valid, Irene has a higher risk of heart failure that will prevent her from joining any deep space Gattaca mission. Vincent also learns that Jerome's paralysis is by his own hand; after coming in second place in a swim meet, Jerome threw himself in front of a car. Jerome maintains that he was designed to be the best, yet wasn't, and that is the source of his suffering.

Vincent repeatedly evades the grasp of the investigation. Finally, it is revealed that Gattaca's mission director was the killer, with the administrator's threats to cancel the mission as a motive. Vincent learns that the detective who closed the case was his brother Anton, who in turn has become aware of Vincent's presence. The brothers meet, and Anton warns Vincent that what he is doing is illegal, but Vincent asserts that he has gotten to this position on his own merits. Anton challenges Vincent to one more game of chicken. As the two swim out in the dead of night, Anton expresses surprise at Vincent's stamina, so Vincent reveals that his strategy for winning was not to save energy for the swim back. Anton turns back and begins to drown, but Vincent rescues him and swims them both back to shore.

On the day of the launch, Jerome reveals that he has stored enough DNA samples for Vincent to last two lifetimes upon his return, and gives him an envelope to open once in flight. After saying goodbye to Irene, Vincent prepares to board but discovers there is a final genetic test, and he currently lacks any of Jerome's samples. He is surprised when Dr. Lamar, the person in charge of background checks, reveals that he knows Vincent has been posing as a valid. Lamar admits that his son looks up to Vincent and wonders whether his son, genetically selected but "not all that they promised", could exceed his potential just as Vincent has. The doctor changes the test results, allowing Vincent to pass. As the rocket launches, Jerome dons his swimming medal and immolates himself in his home's incinerator; Vincent opens the note from Jerome to find only a lock of Jerome's hair. As the movie ends, Vincent muses that "For someone who was never meant for this world, I must confess, I'm suddenly having a hard time leaving it. Of course, they say every atom in our bodies was once a part of a star. Maybe I'm not leaving; maybe I'm going home."

Cast

- Ethan Hawke as Vincent Freeman, impersonating Jerome Eugene Morrow

- Mason Gamble as young Vincent

- Chad Christ as teenage Vincent

- Uma Thurman as Irene Cassini

- Jude Law as Jerome Eugene Morrow

- Loren Dean as Anton Freeman

- Vincent Nielson as young Anton

- William Lee Scott as teenage Anton

- Gore Vidal as Director Josef

- Xander Berkeley as Dr. Lamar

- Jayne Brook as Marie Freeman

- Elias Koteas as Antonio Freeman

- Maya Rudolph as Delivery nurse

- Blair Underwood as Geneticist

- Ernest Borgnine as Caesar

- Tony Shalhoub as German

- Alan Arkin as Detective Hugo

- Dean Norris as Cop on the Beat

- Ken Marino as Sequencing technician

- Cynthia Martells as Cavendish

- Gabrielle Reece as Gattaca Trainer

Production

Filming

The exteriors (including the roof scene) and some of the interior shots of the Gattaca complex were filmed at Frank Lloyd Wright's 1960 Marin County Civic Center in San Rafael, California.[7] The speakers in the complex broadcast announcements both in Esperanto language and English; Miko Sloper from the Esperanto League of North America went to the recording studio to handle the Esperanto part.[8] The parking lot scenes were shot at the Otis College of Art and Design, distinguished by its punch card-like windows, located near Los Angeles International Airport. The exterior of Vincent Freeman's house was shot at the CLA Building on the campus of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Other exterior shots were filmed at the bottom of the spillway of the Sepulveda Dam and outside The Forum in Inglewood. The solar power plant mirrors sequence was filmed at the Kramer Junction Solar Electric Generating Station.

The film is noted for its unique use of color. Cinematographer Slawomir Idziak employed vibrant gold, green, and electric blue tones throughout the film, and shot the film in Super 35mm format, which adds an enlarged layer of grain.

Design

The movie uses a swimming treadmill in the opening minutes to punctuate the swimming and futuristic themes.[9] The production design makes heavy use of retrofuturism; the futuristic electric cars[10] are based on 1960s car models like Rover P6, Citroën DS19 and Studebaker Avanti,[11] futuristic buildings represent modern architecture of the 1950s, and clothing and hairstyles also evoke the 1940s and 1950s.

Title

The film was shot under the working title The Eighth Day, a reference to the seven days of creation in the Bible. However, by the time its release was scheduled for the fall of 1997, the Belgian film Le huitième jour had already been released in the US under the title The Eighth Day. As a result, the film was retitled Gattaca.[12]

Title sequence

The opening title sequence was created by Michael Riley of Shine design studio. It features closeups of body matter (fingernails and hair) hitting the floor accompanied by loud sounds as the objects strike the ground. We later learn that these are the result of Vincent's daily bodily scourings. According to Riley they created oversize models of the fingernails and hair to create the effect.[13]

Release

Box office

Gattaca was released in theaters on October 24, 1997, and opened at number 5 at the box office; trailing I Know What You Did Last Summer, The Devil's Advocate, Kiss the Girls, and Seven Years in Tibet.[14] Over the first weekend the film brought in $4.3 million. It ended its theatrical run with a domestic total of $12.5 million against a reported production budget of $36 million.[15]

Home media

Gattaca was released on DVD on July 1, 1998,[16] and was also released on Superbit DVD.[17] Special Edition DVD and Blu-ray versions were released on March 11, 2008.[18][19] Both editions contain a deleted scene featuring historical figures like Einstein, Lincoln, etc., who are described as having been genetically deficient.[15]

Reception

Critical response

Gattaca received positive reviews from critics. On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes the film received an approval rating of 82% based on 60 reviews, with a rating average of 7.11/10. The site's critical consensus states that "Intelligent and scientifically provocative, Gattaca is an absorbing sci-fi drama that poses important interesting ethical questions about the nature of science."[20] On Metacritic, the film received "generally favorable reviews" with a score of 64 out of 100, based on 20 reviews.[21] Roger Ebert stated, "This is one of the smartest and most provocative of science fiction films, a thriller with ideas."[22] James Berardinelli praised it for "energy and tautness" and its "thought-provoking script and thematic richness."[23]

Although critically acclaimed, Gattaca was not a box office success, but it is said to have crystallized the debate over the controversial topic of human genetic engineering.[24][25][26] The film's dystopian depiction of "genoism" has been cited by many bioethicists and laypeople in support of their hesitancy about, or opposition to, eugenics and the societal acceptance of the genetic-determinist ideology that may frame it.[27] In a 1997 review of the film for the journal Nature Genetics, molecular biologist Lee M. Silver stated that "Gattaca is a film that all geneticists should see if for no other reason than to understand the perception of our trade held by so many of the public-at-large".[28]

In the 2004 book Citizen Cyborg, bioethicist James Hughes in arguing for democratic transhumanism avoiding libertarian transhumanism and bioconservatism, criticized the premise and influence of the film,[29] as fear-mongering and arguing:

- Astronaut-training programs are entirely justified in attempting to screen out people with heart problems for safety reasons;

- In the United States, people are already screened by insurance companies on the basis of their propensities to disease, for actuarial purposes;

- Rather than banning genetic testing or genetic enhancement, society should develop genetic information privacy laws such as the U.S. Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act signed into law on May 21, 2008 that allow justified forms of genetic testing and data aggregation, but forbid those that are judged to result in genetic discrimination. Citizens should then be able to make a complaint to the appropriate authority if they believe they have been discriminated against because of their genotype.

Accolades

| Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Art Direction | Jan Roelfs Nancy Nye |

Nominated |

| Art Directors Guild Award | Excellence in Production Design | Jan Roelfs Sarah Knowles Natalie Richards |

Nominated |

| Bogey Awards | Bogey Award | Won | |

| Gérardmer Film Festival | Special Jury Prize | Andrew Niccol | Won |

| Fun Trophy | Won | ||

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Original Score | Michael Nyman | Nominated |

| Hugo Awards | Best Dramatic Presentation | Andrew Niccol | Nominated |

| London Film Critics' Circle Awards | Best Screenwriter of the Year | Won | |

| Paris Film Festival | Grand Prix | Nominated | |

| Satellite Awards | Best Art Direction and Production Design | Jan Roelfs | Nominated |

| Saturn Awards | Best Costume | Colleen Atwood | Nominated |

| Best Music | Michael Nyman | Nominated | |

| Best Home Video Release | Nominated | ||

| Sitges – Catalan International Film Festival |

Best Motion Picture | Andrew Niccol | Won |

| Best Original Soundtrack | Michael Nyman | Won | |

Soundtrack

| Gattaca: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | ||||

| Released | October 21, 1997 | |||

| Genre | Contemporary classical music, film scores, minimalism | |||

| Length | 54:55 | |||

| Label | Virgin Records America | |||

| Producer | Michael Nyman | |||

| Michael Nyman chronology | ||||

| ||||

The score for Gattaca was composed by Michael Nyman, and the original soundtrack was released on October 21, 1997.[30]

Legacy

Television series

On October 30, 2009, Variety reported that Sony Pictures Television was developing a television adaptation of the feature film as a one-hour police procedural set in the future. The show was to be written by Gil Grant, who has written for 24 and NCIS.[31]

In Time

Writer-director Andrew Niccol has called his 2011 film In Time a "bastard child of Gattaca".[32][33] Both films feature classic cars in a futuristic dystopia; a caste privilege schism which the protagonist challenges; and which prejudices the authorities into neglecting a thorough investigation in favor of condemning the protagonist.

Political references

U.S. Senator Rand Paul used near-verbatim portions of the plot summary from the English Wikipedia entry on Gattaca in a speech at Liberty University on October 28, 2013 in support of Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli's campaign for Governor of Virginia. Paul accused pro-choice politicians of advocating eugenics in a manner similar to the events in Gattaca.[34][35]

See also

- List of films featuring surveillance

- Transhumanism § Genetic divide

- Germinal choice technology

References

- "Gattaca (15)". British Board of Film Classification. November 5, 1997. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- "Gattaca Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- "Gattaca (1997)". Box Office Mojo.

- "Review of Gattaca". Challengingdestiny.com. 2004-02-25. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- "NEUROETHICS | The Narrative Perspectives". Neuroethics.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- Zimmer, Carl (November 10, 2008). "Now: The Rest of the Genome". The New York Times.

- "Gattaca a Not-So-Perfect Specimen", Mick LaSalle, San Francisco Chronicle, Friday, October 24, 1997, URL retrieved 19 February 2009

- https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=tRJF2EhWtz0

- "Endless Pools in the Press". Endlesspools.com. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- https://www.theavanti.com/gattaca.html

- ""Gattaca, 1997": cars, bikes, trucks and other vehicles". IMCDb.org. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- "Gattaca on Hulu". Slashfilm.

- Vlaanderen, Remco. "Gattaca title sequence - Watch the Titles". watchthetitles.com. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- "US Movie Box Office Chart Weekend of October 24, 1997". The Numbers. 1997-10-24. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- "Movie Gattaca - Box Office Data, News, Cast Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- Amazon.com: Gattaca (1997). ISBN 0767805712.

- "Amazon.com: Gattaca (Superbit Collection) (1997)". Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- "Amazon.com: Gattaca (Special Edition) (1997)". Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- "Amazon.com: Gattaca [Blu-ray] (1997)". Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- "Gattaca (1997)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- "Gattaca reviews at". Metacritic.com. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- Roger Ebert (1997-10-24). "Gattaca :: rogerebert.com :: Reviews". Rogerebert.suntimes.com. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- "Review: Gattaca". Reelviews.net. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- Jabr, Ferris (2013). "Are We Too Close to Making Gattaca a Reality?". Retrieved 2014-04-30. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Darnovsky, Marcy (2008). "Are We Headed for a Sci-Fi Dystopia?". Retrieved 2008-03-23. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pope, Marcia; McRoberts, Richard (2003). Cambridge Wizard Student Guide Gattaca. Cambridge University press. ISBN 0-521-53615-4.

- Kirby, D.A. (2000). "The New Eugenics in Cinema: Genetic Determinism and Gene Therapy in GATTACA. Science Fiction Studies, 27: 193-215". Retrieved 2008-01-08. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Silver, Lee M. (1997). "Genetics Goes to Hollywood". Nature Genetics. 17 (3): 260–261. doi:10.1038/ng1197-260.

- Hughes, James (2004). Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-4198-1.

- "Gattaca soundtrack overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- Schneider, Michael (2009-10-29). "Apostle preps for post-'Rescue' life". www.variety.com. Archived from the original on 2010-01-06.

- Capps, Robert (October 6, 2011). "Director Calls In Time 'Bastard Child of Gattaca'". Wired. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- McCarthy, Eric (October 28, 2011). "In Time: Andrew Niccol on His Gattaca-Inspired New Film". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Carroll, James R. (October 28, 2013). "Senator: Scientific advances could bring back eugenics". The Courier-Journal. USA Today. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Kopan, Tal (October 28, 2013). "Rachel Maddow: Rand Paul ripped off Wikipedia". Politico. Sinclair Broadcast Group. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

Further reading

- Frauley, Jon (2010). "Biopolitics and the Governance of Genetic Capital in GATTACA". Criminology, Deviance and the Silver Screen: The Fictional Reality and the Criminological Imagination. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 195–216. doi:10.1057/9780230115361_7. ISBN 978-0230615168.

- Interview with Dr. Paul Durham, Director of Cell Biology and the Center for Biomedical and Life Sciences at Missouri State University, about Gattaca.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gattaca |