Game of Change

The Game of Change was a college basketball game played between the Loyola Ramblers and the Mississippi State Bulldogs on March 15, 1963, during the second round of the 1963 NCAA University Division Basketball Tournament, at Jenison Fieldhouse in East Lansing, Michigan. Taking place in the midst of the American civil rights movement, the game between the integrated Loyola team and the all-white Mississippi State team is remembered as a milestone in the desegregation of college basketball.[1][2]

| 1963 NCAA Tournament Mideast Regional Semifinal | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

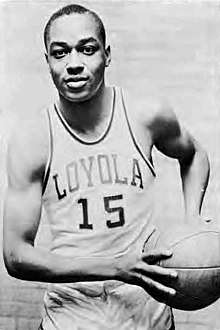

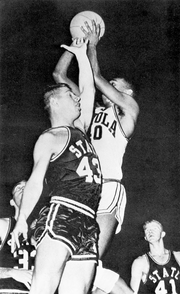

Loyola captain Jerry Harkness about to make a layup over opposing guard Stan Brinker | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Date | March 15, 1963 | ||||||||||||

| Arena | Jenison Fieldhouse | ||||||||||||

| Location | East Lansing, Michigan | ||||||||||||

| Referee(s) | Philip Fox, John Stevens | ||||||||||||

| Attendance | 12,143 | ||||||||||||

In an era when teams typically played no more than two black players at a time, Loyola had four black starters. Persevering through hate mail and racial slurs hurled by segregationists, Loyola finished the 1962–63 regular season with a dominant 24–2 record. Mississippi State came into the postseason with their fourth Southeastern Conference (SEC) title in five years; however, due to an unwritten law that Mississippi teams would never play against black players, they had never before participated in the NCAA tournament. When university president Dean W. Colvard announced that he would send the team to the tournament, several state officials objected and attempted to restrain the team in the state. Employing a plan involving decoy players, the Bulldogs avoided being served an injunction as they took a charter plane to Michigan the day before the game.

Loyola advanced to the second round after beating Tennessee Tech by 69 points, the largest margin of victory in tournament history, while Mississippi State had a first round bye. The game was preceded by a handshake between Jerry Harkness, a black Loyola player, and Joe Dan Gold, a white Mississippi State player. Loyola won the game by the score of 61–51 and ultimately won the entire NCAA tournament with a victory over Cincinnati in the championship game.

Background

Loyola-Chicago

In the early 1960s, college basketball had an unwritten rule that teams should only play two or three black players at a time.[3] Loyola, however, started four black players throughout their 1962–63 season.[1] Head coach George Ireland decided to defy the norms because he was "tired of losing", according to John Egan, the lone white starter on the 1963 team.[4] According to Ireland, this made him unpopular in the basketball world; he once said that other coaches "used to stand up at banquets and say, 'George Ireland isn't with us tonight because he's in Africa — recruiting.'"[5]

Loyola's 1962–63 season went very well on the court, and they concluded the regular season with a 24–2 record. They consistently remained in the top five rankings throughout their campaign, and ultimately finished at No. 3 in the AP Poll and No. 4 in the Coaches Poll.[6] However, they regularly faced harsh discrimination. In a road match at Houston on February 23, members of the crowd shouted racial slurs and threw popcorn and ice.[4]

On February 18, Loyola was awarded one of eleven at-large bids for the tournament.[7] In the first round game on March 11, the Ramblers defeated Tennessee Tech 111–42, the largest margin of victory in tournament history as of 2020. This led them to face Mississippi State, who'd had a first round bye, in the Mideast regional semifinal on the campus of Michigan State University in East Lansing, Michigan.[1]

Mississippi State

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, head coach Babe McCarthy led the Mississippi State Bulldogs to much success in the Southeastern Conference (SEC). Starting with the 1958–59 season, they won the SEC title four times in five years.[8] The Bulldogs' 1962–63 season was no exception, as they won the SEC title outright with a win over Ole Miss on March 2,[8] and never fell below a No. 11 ranking in either poll for the duration of the season. They finished the season at #6 in the AP Poll and #7 in the Coaches Poll.[6] They finished the regular season with a 21–5 overall record and a 12–2 record in conference play.[9]

However, the all-white Mississippi State team had limited itself to only competing against other all-white teams. They remained confined to the South for all their regular season games, and had declined NCAA tournament invitations in previous seasons to avoid facing integrated teams.[1] At that time, there existed an "unwritten law" within the state that no Mississippi team would ever play against a team with black players.[10] However, as the civil rights movement was gaining traction around the country, this rule began to face scrutiny and opposition. On February 26, 1963, Mississippi State's student senate voted unanimously to recommend that the Bulldogs accept the tournament invitation, and the following day, they gathered 2,000 student signatures on a resolution to the same effect.[11]

The decision ultimately fell upon Dean W. Colvard, president of Mississippi State University. On March 2, 1963, Colvard issued a statement announcing that he would be sending the team to the tournament "unless hindered by competent authority."[12]

Colvard's decision sparked widespread debate within the state of Mississippi. Several Mississippi legislators, including State Sen. Billy Mitts, State Rep. Russell Fox, and State Rep. Walter Hester, expressed their disapproval of the decision. In a statement, Hester wrote, "This action follows the Meredith incident as an admission that Miss. State has capitulated and is willing for the Negroes to move into that school en masse,"[13] referring to James Meredith's enrollment as the first black student at University of Mississippi after a 1962 riot. State Sen. Sonny Montgomery, on the other hand, indicated his support for Colvard's decision.[13] Sending the team to the tournament was also favored by the players themselves, who unanimously indicated their desire to play when interviewed by The Clarion-Ledger,[14] as well as by the general public, with a locally conducted poll reporting 85% approval.[8]

On March 5, the state college board announced they would be holding a special session to review Colvard's decision. The meeting was convened by trustee M. M. Roberts of Hattiesburg, whom Sports Illustrated describes as a "tenacious lawyer and proud racist".[8] When the board met several days later in Jackson, Mississippi, protesters and petitioners on both sides of the debate were present outside the building. The board voted 8–3 in support of the tournament decision, and 9–2 in a vote expressing confidence in Colvard's leadership.[8]

Nevertheless, participation in the game was still opposed by many in the state, including Gov. Ross R. Barnett.[1] On March 13, State Sen. Billy Mitts obtained a temporary injunction from a Mississippi Chancery Court that, if served, would have prevented the team from leaving the state.[15] That night, the injunction was reportedly received by the Oktibbeha County deputy sheriff.[16] Fearing being stopped by authorities if he were named in the injunction, coach Babe McCarthy left the state early, driving himself north to Nashville to be joined by the rest of the team later.[10]

On the morning of March 14, the day before the game was to be played, the team sent trainer Dutch Luchsinger and five reserve players to Starkville airport at 8 a.m. as decoys. Had they been served an injunction while trying to board, the rest of the team would have taken a private plane to Nashville and flown commercially to Michigan. However, due to a weather delay in Atlanta, the plane was late to arrive in Starkville. The deputy sheriff reportedly came to the airport with an injunction to serve, but did not find the plane or the team. The reserve squad did not encounter the deputy sheriff when they arrived, and thus returned to campus to reunite with the rest of the team. Thirty minutes later, they received word that the plane was en route, and the entire team headed to the airport together. The deputy sheriff was not present when they arrived, and their plane successfully took off at 9:44 a.m.[16] They stopped over in Nashville to pick up McCarthy before proceeding to Michigan, where the game would be held the next day.[10]

Game summary

On game day, Jenison Fieldhouse was packed with a reported crowd of 12,143 in the 12,500-capacity gym.[17] The game was preceded with a handshake between Jerry Harkness, a black Loyola player, and Joe Dan Gold, a white Mississippi State player.[18] In a 2013 interview, Harkness told NPR of the moment: "The flashbulbs just went off unbelievably, and at that time, boy, I knew that this was more than just a game. This was history being made."[3]

Despite the circumstances, the game itself was played without incident. The underdog Mississippi State team started out with a 0–7 lead, holding Loyola scoreless for nearly the first five minutes.[17] Ron Miller ended the shutout, scoring Loyola's first basket at 14:11. His teammate Jerry Harkness shortly followed it with two three-point plays to bring the game to a 12–12 tie.[19] By halftime, Loyola led Mississippi State 26–19.[20]

With Vic Rouse and Les Hunter dominating in field goals and rebounds, Loyola stretched their lead to 39–29 with 13:15 left in the second half. However, Mississippi State's offense picked up the slack and narrowed the score to 41–38 with 10:55 remaining. Mississippi State remained competitive in the game until forward Leland Mitchell, their leading scorer and rebounder, fouled out with 6:47 left. Loyola's lead swelled to 57–42, and the Bulldogs were never able to recover.[19] The Ramblers won with a final score of 61–51.[20]

After the game, Loyola coach George Ireland praised Mississippi State as "the most deliberate offense we ran into all year".[21] Bulldogs coach Babe McCarthy attributed Loyola's win to strength in rebounding, and said he thought his team would have had to play "a near perfect game" to beat the Ramblers.[21]

Box score

Friday, March 15 |

| Mississippi State 51, Loyola-Chicago 61 | ||

| Scoring by half: 19–26, 32–35 | ||

| Pts: L. Mitchell – 14 Rebs: L. Mitchell – 11 |

Pts: J. Harkness – 20 Rebs: V. Rouse – 19 | |

| Legend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Jersey number | Pos | Position | FGM | Field goals made |

| FGA | Field goals attempted | FTM | Free throws made | FTA | Free throws attempted |

| Reb | Rebounds | PF | Personal fouls | Pts | Points |

| No. | Player | Pos | FGM | FGA | FTM | FTA | Reb | PF | Pts | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44 | Leland Mitchell | F | 6 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 14 | ||||||||

| 33 | Joe Dan Gold | F | 3 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 11 | ||||||||

| 42 | Doug Hutton | G | 5 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 10 | ||||||||

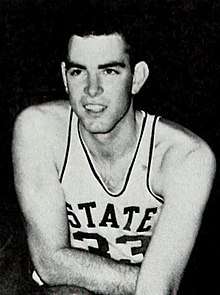

| 53 | Stan Brinker | G | 3 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 9 | ||||||||

| 41 | Red Stroud | G | 3 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 | ||||||||

| 43 | Aubrey Nichols | G | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Team totals | 20 | 49 | 11 | 20 | 25 | 14 | 51 | ||||||||||

| Statistics from Sports-Reference.com,[22] rosters from game program[23] | |||||||||||||||||

| No. | Player | Pos | FGM | FGA | FTM | FTA | Reb | PF | Pts | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | Jerry Harkness | F | 7 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 20 | ||||||||

| 40 | Vic Rouse | F | 8 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 4 | 16 | ||||||||

| 41 | Les Hunter | C | 3 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 12 | ||||||||

| 42 | Ron Miller | G | 5 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 11 | ||||||||

| 11 | John Egan | G | 1 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | ||||||||

| 23 | Chuck Wood | G/F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | ||||||||

| Team totals | 24 | 66 | 13 | 16 | 44 | 17 | 61 | ||||||||||

| Statistics from Sports-Reference.com,[22] rosters from game program[23] | |||||||||||||||||

Aftermath

After defeating Mississippi State, Loyola advanced to the title game with relative ease. On March 16, they defeated Illinois 79–64 in the regional final, and on March 22, they defeated Duke 94–75 in the national semifinal.[24] In the championship game, the Ramblers went to overtime against Cincinnati before ultimately winning by a score of 60–58. It was the first national championship in Loyola-Chicago history, and as of 2020, it remains the only national championship for the state of Illinois.[1]

The day after the Loyola game, Mississippi State faced Bowling Green in a consolation game. They won 65–60, and returned to Starkville as the third place team from the Mideast region. Upon landing at the airport in Mississippi, they were greeted by a crowd of 700 fans. In 1965, Mississippi State became an integrated campus when Richard Holmes became the first black student to enroll.[8]

Legacy

The 50th anniversary of the Game of Change was marked with a number of commemorative events. On December 15, 2012, Mississippi State visited Loyola for the teams' first meeting since the 1963 tournament. With surviving players from both of the historic teams present, Loyola won by a score of 59–51.[25][26] On July 10–11, 2013, members of the 1962–63 Loyola team reunited for a two-day trip to Washington, D.C. On the first day, they toured the Capitol Building and met privately with Senator Dick Durbin and House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi,[27] and on July 11, they met with President Barack Obama in the Oval Office.[28] On November 24, 2013, the 1962–63 Loyola team was inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame, the first time an entire team was inducted collectively.[27][29] The team was also inducted into the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame on September 18, 2013.[27][30]

The overall significance of the Game of Change to the civil rights movement has been debated. The 1962–63 Loyola Ramblers are often overlooked, or overshadowed by the 1965–66 Texas Western Miners, who won the 1966 NCAA Championship with an all-black starting lineup over an all-white Kentucky team.[31][32] In a 2018 opinion piece for The Washington Post, Kevin Blackistone argues that the game did not actually bring about much change. Blackistone points to significant setbacks that the movement faced in Mississippi after the game, such as the murder of Vernon Dahmer and the shooting of James Meredith at the March Against Fear, and suggests that the modern narrative of the game is more of a societal myth than a truthful retelling.[2] In a response letter to the editor, journalist Charles Paikert contends that, although the game did not cause sudden major change to ongoing racial tensions in the South, it did show that white athletes and students rejected the unwritten rule against interracial sports competitions. He further writes that the national publicity garnered by Loyola's championship run was a "big deal" in 1963.[33]

References

- Mather, Victor (March 29, 2018). "When Loyola-Chicago Broke a Racial Barrier 55 Years Ago". The New York Times. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Blackistone, Kevin (March 22, 2018). "What did the Game of Change really change? Not much, despite what you might hear". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Corley, Cheryl (March 15, 2013). "Game Of Change: Pivotal Matchup Helped End Segregated Hoops". NPR.org. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Gregory, Sean (March 30, 2018). "How Loyola Chicago's Basketball Team Shattered a Racial Barrier". Time. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Goldstein, Richard (September 20, 2001). "George Ireland, 88, Title-Winning Coach at Loyola, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- "1962-63 College Basketball Polls". College Basketball at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC.

- "5 Fives Accept Bids to N.C.A.A. Tourney". The New York Times. New York. February 19, 1963. p. 16. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Wolff, Alexander (March 10, 2003). "Ghosts of Mississippi". Sports Illustrated. 98 (10). Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- "2019–20 Mississippi State Men's Basketball Media Guide" (PDF). Mississippi State University Athletics. November 4, 2019. p. 256. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- "Miss. State Five Flees Injunction". The New York Times. East Lansing, Michigan. United Press International. March 15, 1963. p. 16. ProQuest 116645293. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- "MSU Student Senate Votes to Go NCAA". The Clarion-Ledger. Jackson, Mississippi. March 3, 1963. p. 4-C. Retrieved June 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Colvard, D. W. (March 2, 1963). "Statement by D. W. Colvard, President of Mississippi State University, Relative to Participation in NCAA Championship Competition" (Press release). Retrieved June 10, 2020 – via Mississippi State University Libraries.

- "MSU Entry Brings Additional Criticism". The Clarion-Ledger. March 5, 1963. p. 1. Retrieved June 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Fulton, Robert (March 9, 1963). "High 'N Inside: To The Man, State's Cage Squad Wants Trip To NCAA". The Clarion-Ledger. p. 7. Retrieved June 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Bulldogs Head for Tournament". Enterprise-Journal. Associated Press. March 14, 1963. p. 9. Retrieved June 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Fulton, Robert (March 15, 1963). "Bulldog Cagers Arrive For NCAA Play Friday". The Clarion-Ledger. p. 25. Retrieved June 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Liska, Jerry (March 16, 1963). "Mississippi State Falls Before Chicago Loyola". The Decatur Daily. East Lansing, Michigan. Associated Press. p. 6. Retrieved May 29, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- O'Neil, Dana (December 13, 2012). "A game that should not be forgotten". ESPN.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Damer, Roy (March 16, 1963). "Loyola, Illinois Win; Meet Tonight!". Chicago Tribune. sec. 3, p. 1. Retrieved June 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hallas, Clark (March 16, 1963). "Loyola of Chicago Cagers Triumph in Region Playoff". Shamokin News-Dispatch. United Press International. p. 6. Retrieved May 29, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "If Ireland Had His Druthers, It'd Be Ohio". Chicago Tribune. March 16, 1963. sec. 3, p. 2. Retrieved June 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mississippi State vs. Loyola (IL) Box Score, March 15, 1963". College Basketball at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- Mideast Regional Basketball Tournament Official Program (Game program), NCAA, March 15, 1963 – via Mississippi State University Libraries

- "Loyola Men's Basketball 2018–19 Media Guide" (PDF). Loyola University Chicago Athletics. 2018. p. 39. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Sumrak, Seanna Mullen. "Game of Change: The Matchup That Transformed College Basketball". Loyola University Chicago. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- "Mississippi State vs. Loyola (IL) Box Score, December 15, 2012". College Basketball at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- "Loyola 1963 Basketball Team To Visit With President Obama". Loyola University Chicago Athletics. July 11, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Jarrett, Valerie (July 11, 2013). "The Game of Change Comes to the White House". The White House. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- "1963 Loyola University Team: Class of 2013". The College Basketball Experience. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- "Loyola 1963 Men's Basketball Team To Enter Chicagoland Sports Hall Of Fame". Loyola University Chicago Athletics. June 7, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Moser, Whet (July 15, 2013). "Why the Pathbreaking 1963 Loyola Ramblers Met President Obama". Chicago. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Lopresti, Mike (March 13, 2013). "Loyola-Chicago's groundbreaking title overlooked today". USA Today. Gannett Company. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Paikert, Charles (April 6, 2018). "The 'Game of Change' mattered". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

Further reading

- Lenehan, Michael (2013). Ramblers: Loyola Chicago 1963—The Team That Changed the Color of College Basketball. Agate Publishing. ISBN 1572847212.

- Veazey, Kyle (2012). Champions for Change: How the Mississippi State Bulldogs and Their Bold Coach Defied Segregation. The History Press. ISBN 1614237220.

- Freedman, Lew (2014). Becoming Iron Men: The Story of the 1963 Loyola Ramblers. Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 0896728773.

- Peterson, Jason A. (2016). Full Court Press: Mississippi State University, the Press, and the Battle to Integrate College Basketball. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1496808231.

- Mitchell, Fred (2019). The History of Loyola Basketball: More Than a Shot and a Prayer. Post Hill Press. ISBN 1642930652.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Game of Change. |

- Box score at Sports-Reference

- "Game of Change: The Matchup That Transformed College Basketball" at Loyola University Chicago