Michigan State University

Michigan State University (MSU) is a public research university in East Lansing, Michigan. MSU was founded in 1855 and served as a model for land-grant universities later created under the Morrill Act of 1862.[7] The university was founded as the Agricultural College of the State of Michigan, one of the country's first institutions of higher education to teach scientific agriculture.[8] After the introduction of the Morrill Act, the college became coeducational and expanded its curriculum beyond agriculture. Today, MSU is one of the largest universities in the United States (in terms of enrollment) and has approximately 634,300 living alumni worldwide.[5]

| |

| Motto | |

|---|---|

| Type |

|

| Established | February 12, 1855 |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $3.03 billion (2019)[4] |

| President | Samuel L. Stanley |

Academic staff | 5,703 (2020)[5] |

Administrative staff | 7,365 (2020)[5] |

| Students | 49,809 (Fall 2019)[5] |

| Undergraduates | 39,176 (Fall 2019)[5] |

| Postgraduates | 10,633 (Fall 2019)[5] |

| Location | , , United States 42°43′30″N 84°28′48″W |

| Campus | Suburban 5,300 acres (21 km2)[5] |

| Colors | Green and white[6] |

| Nickname | Spartans |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division I – Big Ten |

| Mascot | Sparty |

| Website | www |

| |

U.S. News & World Report ranks its graduate programs the best in the U.S. in elementary teacher's education, secondary teacher's education, industrial and organizational psychology, rehabilitation counseling, African history (tied), supply chain logistics and nuclear physics in 2019. MSU pioneered the studies of packaging, hospitality business, supply chain management, and communication sciences. Michigan State is a member of the Association of American Universities, an organization of 65[9] leading research universities in the US and Canada. The university's campus houses the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory, the W. J. Beal Botanical Garden, the Abrams Planetarium, the Wharton Center for Performing Arts, the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, and the country's largest residence hall system.[10]

The Michigan State Spartans compete in the NCAA Division I Big Ten Conference. Michigan State Spartans football won the Rose Bowl Game in 1954, 1956, 1988 and 2014, and a total of six national championships.[11] Spartans men's basketball won the NCAA National Championship in 1979 and 2000 and has attained the Final Four eight times since the 1998–1999 season. Spartans ice hockey won NCAA national titles in 1966, 1986 and 2007. The women’s cross country team was named Big Ten champions in 2019.[12] In the fall of 2019, MSU student-athletes posted all-time highs for graduation success rates and federal graduation rates, according to NCAA statistics.[13]

History

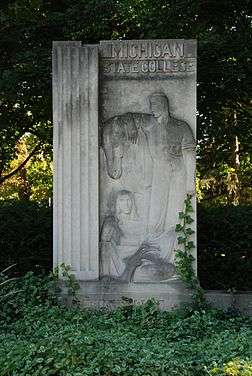

Agricultural Roots

The Michigan Constitution of 1850 called for the creation of an "agricultural school,"[14] though it was not until February 12, 1855, that Michigan Governor Kinsley S. Bingham signed a bill establishing the United States' first agricultural college, the Agricultural College of the State of Michigan.[15] Classes began on May 13, 1857, with three buildings, five faculty members, and 63 male students.

The first president, Joseph R. Williams, encouraged a curriculum that required more scientific study than practically any undergraduate institution of the era. It balanced science, liberal arts, and practical training. The curriculum excluded Latin and Greek studies since most applicants did not study any classical languages in their rural high schools. However, it did require three hours of daily manual labor, which kept costs down for both the students and the College.[16] Despite Williams' innovations and his defense of education for the masses, the State Board of Education saw Williams' curriculum as elitist. They forced him to resign in 1859 and reduced the curriculum to a two-year vocational program.

Land-Grant pioneer

In 1860, Williams became acting lieutenant governor[17] and helped pass the Reorganization Act of 1861. This restored the college's four-year curriculum and gave the college the power to grant master's degrees. Under the act, a newly created body, known as the State Board of Agriculture, took over from the State Board of Education in running the institution.[15] The college changed its name to State Agricultural College, and its first class graduated in the same year. As the Civil War had begun, there was no time for an elaborate graduation ceremony. The first alumni enlisted to the Union Army. Williams died, and the following year, Abraham Lincoln signed the First Morrill Act of 1862 to support similar colleges, making the Michigan school a national model. Shortly thereafter, on March 18, 1863, the state designated the college its land-grant institution making Michigan State University one of the nation's first land-grant colleges.[18]

Co-ed college

The college first admitted women in 1870, although at that time there were no female residence halls. The few women who enrolled boarded with faculty families or made the arduous stagecoach trek from Lansing. From the early days, female students took the same rigorous scientific agriculture courses as male students. In 1896, the faculty created a "Women Course" that melded a home economics curriculum with liberal arts and sciences. That same year, the College turned the Abbot Hall male dorm into a women's dormitory. It was not until 1899 that the State Agricultural College admitted its first African American student, William O. Thompson. After graduation, he taught at what is now Tuskegee University. President Jonathan L. Snyder invited its president Booker T. Washington to be the Class of 1900 commencement speaker. A few years later, Myrtle Craig became the first woman African American student to enroll at the College. Along with the Class of 1907, she received her degree from U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, commencement speaker for the Semi-Centennial celebration. The City of East Lansing was incorporated the same year,[19] and two years later the college changed its name to Michigan Agricultural College (M.A.C.).

Big Ten university

During the early 20th century, M.A.C. expanded its curriculum well beyond agriculture. By 1925 it had expanded enough to change its name to Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science (M.S.C.). In 1941, the Secretary of the State Board of Agriculture, John A. Hannah, became president of the College.

After World War II, he began the largest expansion in the institution's history, with the help of the 1945 G.I. Bill, which helped World War II veterans gain college educations. One of Hannah's strategies was to build a new dormitory building, enroll enough students to fill it, and use the income to start construction of another dormitory. Under his plan, enrollment increased from 15,000 in 1950 to 38,000 in 1965.[20]

In 1957, Hannah continued MSU's expansion by co-founding Michigan State University–Oakland, now Oakland University, with Matilda Dodge Wilson. Hannah also got the chance to improve the athletic reputation of M.S.C. when the University of Chicago resigned from the Big Ten Conference in 1946. Hannah lobbied to take its place, gaining admission in 1949.[21]

Six years later, in its Centennial year of 1955, the State of Michigan renamed the College as Michigan State University of Agriculture and Applied Science.[22] Nine years afterward, the University governing body changed its name from the State Board of Agriculture to the MSU Board of Trustees. The State of Michigan[23] allowed the University to drop the words "Agriculture and Applied Science" from its name. Since 1964, the institution has been Michigan State University.

Oakland University

In 1957, the donation of 1,500 acres (6.1 km2) in Pontiac Township, Oakland County, Michigan prompted creation of Michigan State University – Oakland. That campus became the independent school Oakland University in 1970.[24]

Global Leadership Initiative, 2012 and Beyond

Since the end of the Hannah era in 1969, Michigan State shifted its focus from increasing the size of its student body to advancing its national and global reputation. In September 2005, President Lou Anna Simon called for MSU to become the global model leader for Land-Grant institutions by 2012. Her plans included creating a new residential college and increased grants awarded from the National Institutes of Health past the US$100 million mark. While there are over 100 Land-grant universities in the United States, she stated she would like Michigan State University to be the leader.[25]

Michigan State, the University of Michigan and Wayne State University created the University Research Corridor in 2006.[26] This alliance was formed to transform and strengthen Michigan's economy by reaching out to businesses, policymakers, innovators, investors and the public to speed up technology transfer, make resources more accessible and attract new jobs to the state.[26]

Sexual assault investigation

On May 1, 2014, Michigan State University was named one of fifty five higher education institutions under investigation by the Office of Civil Rights “for possible violations of federal law over the handling of sexual violence and harassment complaints” by Barack Obama's White House Task Force To Protect Students from Sexual Assault.[27] "The investigation at Michigan State involves its response to sexual harassment and sexual assault complaints involving students," according to one reporter.[28] It was later reported in the same paper that "An investigation by the U.S. Department of Education into how Michigan State University handles sexual assault complaints was spurred by an incident in Wonders Hall in August 2010, a spokesman said."[29]

USA Gymnastics sex abuse scandal

In 2016, a police report was filed alleging that in 2000, USA Gymnastics team doctor and MSU sports physician Larry Nassar (also a professor in the College of Osteopathic Medicine) had sexually assaulted a minor named Rachael Denhollander under the guise of medical treatment.[30] The allegation led to the arrest and eventual conviction of Nassar. He was sentenced in January 2018. Between the police report filing and the time of sentencing, 156 victims including Olympic gymnasts and MSU student athletes came forward to speak of abuses inflicted by Nassar. The Detroit News reported that 14 MSU representatives – including athletic trainers, coaches, a university police detective, and administrators – had possibly been alerted of sexual misconduct by Nassar across two decades, with notification of an incident in 2014 documented by a Title IX investigation.[31] Michigan State and USA Gymnastics have been accused of enabling Nassar's abuse[32][33][34] and are named as defendants in civil lawsuits that gymnasts and former MSU student athletes have filed against Nassar.[35][36] On May 16, 2018, it was announced that Michigan State University had agreed to pay the victims of Nassar $500 million.[37]

MSU's role in the scandal led to the resignation of president Simon in January 2018 due to mounting pressure from the public and alumni, as well as the retirement of athletic director Mark Hollis.[38][39] In March 2018, William Strampel was arrested and charged with felony misconduct in office and criminal sexual conduct for allegedly groping a student and storing nude photos of female students on his computer. Strampel is the former dean of the College of Osteopathic Medicine and oversaw Larry Nassar's clinic.[40] On November 20, 2018, former university president Simon was charged with two felonies and two misdemeanor counts for lying to the police about her knowledge of sexual abuse committed by Nassar. The case is currently going through the legal process with Simon maintaining her innocence.[41] In January 2019, interim president John Engler, who had replaced Simon, resigned after a pattern of controversial comments about the ongoing scandal including that Nassar's victims were "enjoying" the spotlight.[42]

Campus

MSU's sprawling campus is in East Lansing, Michigan. The campus is perched on the banks of the Red Cedar River. Development of the campus started in 1856 with three buildings: a multipurpose College Hall building, a dormitory later called "Saints' Rest",[43] and a barn. Today, MSU's contiguous campus consists of 5,300 acres (21 km2),[5] 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) of which are developed. There are 563[5] buildings: 107[5] for academics, 131 for agriculture, 166 for housing and food service, and 42 for athletics. Overall, the university has 22,763,025 square feet (2,114,754.2 m2) of indoor space.[44] Connecting it all is 26 miles (42 km) of roads and 100 miles (160 km) of sidewalks.[45] MSU also owns 44 non-campus properties, totaling 22,000 acres (89 km2) in 28 different counties.[46]

In early 2017, construction of a $22.5 million solar project began at five parking lots on campus. MSU's solar carport array is constructed on five of the university's largest commuter parking lots and covers 5,000[48] parking spaces. The solar carports are designed to deliver a peak power of 10.5 Megawatts and an annual energy of 15 million kilowatt-hours, which is enough to power approximately 1,800 Michigan homes.[49] The solar carport project was recognized at the Smart Energy Decisions Innovation Summit 2018, earning the Onsite Renewable Energy award for “The Largest Carport Solar Array in North America.”[50]

North campus

The oldest part of campus lies on the Red Cedar river's north bank.[51] It includes Collegiate Gothic architecture, plentiful trees, and curving roads with few straight lines. The College built its first three buildings here, of which none survive. Other historic buildings north of the river include the president's official residence, Cowles House; and Beaumont Tower, a carillon clock tower marking the site of College Hall, the original classroom building. To the east lies Eustace–Cole Hall, America's first freestanding horticulture laboratory.[52] Other landmarks include the bronze statue of former president John A. Hannah,[53] the W. J. Beal Botanical Garden, and the painted boulder known as "The Rock", a popular spot for theatre, tailgating, and candlelight vigils. On the campus's northwest corner is the University's hotel, the Kellogg Hotel and Conference Center. The university also has a museum, initiated in 1857. MSU Museum is one of the Midwest's oldest museums and is accredited by the American Alliance of Museums.[54]

South campus

The campus south of the river consists mostly of post-World War II International Style buildings, and is characterized by sparser foliage, relatively straight roadways, and many parking lots. The "2020 Vision" Master Plan proposes replacing these parking lots with parking ramps and green space,[55] but these plans will take many years to reach fruition. As part of the master plan, the University erected a new bronze statue of The Spartan in 2005 to be placed at the intersection of Chestnut and Kalamazoo, just south of the Red Cedar River. This replica replaced the original modernist terra cotta statue,[56] which can still be seen inside Spartan Stadium. Notable academic and research buildings on the South Campus include the Cyclotron, the College of Law, the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB), Interdisciplinary Science and Technology Building,[57] and the Broad College of Business.[58]

This part of campus is home to the MSU Horticulture Gardens and the adjoining 4-H Children's Garden. South of the gardens lie the Canadian National and CSX railroads, which divide the main campus from thousands of acres of university-owned farmland. The university's agricultural facilities include the Horse, Dairy Cattle, Beef Cattle, Swine, Sheep, and Poultry Teaching and Research Farms, as well as the Air Quality Control Lab and the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory.[59]

Kellogg Hotel and Conference Center

The Kellogg Hotel and Conference Center doubles as a 4-star hotel and a business-friendly conference center. It is on the northwest corner of Michigan State University's campus, across from the Brody Complex, on Harrison Road just south of Michigan Avenue. The hotel's 160 rooms and suites can accommodate anyone staying in East Lansing for a business conference, sporting event or an on-campus visit. Besides a lodging facility, the Kellogg Hotel and Conference Center is a "learning laboratory for the 300–400 students each year that are enrolled in The School of Hospitality Business and other majors." The Kellogg Hotel and Conference Center strives to facilitate education by hosting conferences and seminars.[60]

Dubai campus

MSU ran a small campus at Dubai Knowledge Village, Dubai, United Arab Emirates.[61] It first offered only one program, a master's program in human resources and labor relations. In 2011, it added a master's program in Public Health.[62]

Previously, MSU established an education center in Dubai that offered six undergraduate programs, thereby becoming the first American university with a presence in Dubai International Academic City. The University attracted 100 students in 2007, its first year,[63] but the school was unable to achieve the 100–150 new students per year needed for the program to be viable, and in 2010 MSU closed the program and the campus.[62][64][65]

Academics

Admissions

Michigan State offers a rolling admissions system, with an early admission deadline in October. MSU is considered "more selective" by U.S. News & World Report.[66] For the Class of 2022 (enrolling Fall 2018), MSU received 33,129 applications and accepted 25,733 (77.7%), with 8,688 enrolling.[67] The middle 50% range of SAT scores for enrolling freshmen was 560-650 for reading and writing, and 550-660 for math.[67] The middle 50% ACT composite score range was 23–29.[67] The average high school grade point average (GPA) was 3.73.[67]

For Fall 2019 MSU received over 44,000 freshman applications.[68]

| 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Time Undergraduate Applicants | 44,321 | 33,129 | 36,143 | 37,480 | 35,303 |

| Admits | 31,522 | 25,733 | 25,860 | 24,641 | 23,400 |

| % Admitted | 71.1 | 77.7 | 71.5 | 65.7 | 66.3 |

| Enrolled | 8,527 | 8,395 | 8,066 | 7,911 | 7,929 |

| Avg GPA | 3.76 | 3.73 | 3.71 | 3.70 | 3.68 |

| Avg ACT | 26.2 | 26.0 | 25.9 | 26.1 | 25.7 |

| Avg SAT Composite | 1,218 | 1,213 | 1,205 | 1,128 | 1,129 |

MSU tied for 10th place among universities with the largest student enrollment in the U.S. for fall 2018.[70] For the fiscal year of 2018–19, the Office of the Registrar conferred 12,354 degrees.[71] The student body is 52% female and 48% male.[5] While 75.1% of students come from all 83 counties in the State of Michigan,[5] also represented are all 50 states in the U.S. and 138 other countries.[5]

In Fall 2019, 5,660 international students enrolled at MSU, with the top five countries outside North America being China (2,965), India (506), South Korea (331), Saudi Arabia (222) and Taiwan (144).[72] According to a Brookings Institution report analyzing foreign student visa approvals from 2008–2012, MSU once enrolled the highest number of Chinese international students in the United States, with roughly 4,700 Chinese citizens enrolled during the period of the study.[73] MSU has since seen decreased Chinese enrollment and has lost its status as the top destination of Chinese students, which former Michigan Department of Education head Tom Watkins attributed to a ramp-up in anti-China rhetoric by U.S. President Donald Trump and changes in Chinese domestic conditions.[74]

MSU has about 5,703 faculty and 7,365 staff members.[5] Listed as a Public Ivy,[75] Michigan State is a member of the Association of American Universities. Michigan State University Ombudsperson is the longest continually operating ombudsman office at a college or university in the country.[76] MSU's study abroad program is amongst the 10 largest of any single-campus university in the United States with 2,755[77] MSU students studying abroad in 2017–18 in over 60 countries on all continents, including Antarctica.[78]

Rankings

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| ARWU[79] | 46-58 |

| Forbes[80] | 159 |

| Times/WSJ[81] | 81 |

| U.S. News & World Report[82] | 84 |

| Washington Monthly[83] | 38 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[84] | 101–150 |

| QS[85] | 157 |

| Times[86] | 84 |

| U.S. News & World Report[87] | 101 |

|

USNWR graduate school rankings[88] | |

|---|---|

| Business | 40 |

| Education | 24 |

| Engineering | 58 |

| Law | 93 |

| Medicine: Primary Care | 67 |

| Nursing: Doctorate | 90 |

| Nursing: Master's | 64 |

|

USNWR departmental rankings[88] | |

|---|---|

| Biological Sciences | 46 |

| Chemistry | 48 |

| Clinical Psychology | 43 |

| Computer Science | 55 |

| Criminology | 10 |

| Earth Sciences | 64 |

| Economics | 29 |

| English | 60 |

| Fine Arts | 53 |

| History | 44 |

| Mathematics | 47 |

| Nursing–Anesthesia | 29 |

| Physics | 28 |

| Political Science | 29 |

| Psychology | 45 |

| Rehabilitation Counseling | 1 |

| Social Work | 36 |

| Sociology | 42 |

| Speech–Language Pathology | 38 |

| Statistics | 50 |

| Veterinary Medicine | 17 |

In its 2020 rankings, Times Higher Education World University Rankings ranked MSU 26th in public schools, 36th overall in the United States, and 84th in the world. Michigan State ranks 101–150 in the world in 2016, according to the Academic Ranking of World Universities. The 2020 QS World University Rankings placed it at 144th internationally.[89] In its 2020 edition, U.S. News & World Report ranked it as tied for the 34th among best public university in the United States, tied for 84th nationally and tied for 52nd among best universities for veterans.[90]

The university has over 200 academic programs. U.S. News ranked MSU's graduate-level programs first in elementary teacher's education and secondary teacher's education for 26 straight years, African history (tied), curriculum and instruction (tied), industrial and organizational psychology, nuclear physics, rehabilitation counseling (tied), and supply chain logistics in the U.S. for 2020.[88]

The Eli Broad College of Business was ranked No. 39th nationally for 2019-20 by Bloomberg Businessweek. Ninety-two percent of the school's graduates received job offers in 2019.[91] The latest edition of U.S. News ranked Michigan State's undergraduate and graduate supply chain management/logistics programs in the Eli Broad College of Business 1st in the nation.[90] In addition, the Eli Broad College of Business undergraduate accounting program is ranked 22nd, the master's accounting program is ranked 15th, and the doctoral program is ranked 18th, according to the 2018 Public Accounting Report's Annual Survey of Accounting Professors.[92] The MBA program is ranked 27th in the U.S. by Forbes magazine.[93]

The College of Communication Arts and Sciences was established in 1955 and was the first of its kind in the United States.[94] The college's Media and Information Studies doctoral program was ranked No. 2 in 2007 by The Chronicle of Higher Education in the category of mass communication.[94] The communication doctoral program was ranked No. 4 in a separate category of communication in The Chronicle of Higher Education's 2005 Faculty Scholarly Productivity Index, published in 2007.[94] The college's faculty and alumni include eight Pulitzer Prize winners and a two-time Emmy Award winning recording mixer.[94]

Collections and museum

The Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum is the university's contemporary art museum. Michigan State University Libraries comprise North America's 29th largest academic library system with over 4.9 million volumes and 6.7 million microforms.[95]

Research

The university has a long history of academic research and innovation. In 1877, botany professor William J. Beal performed the first documented genetic crosses to produce hybrid corn, which led to increased yields. MSU dairy professor G. Malcolm Trout improved the process for the homogenization of milk in the 1930s, making it more commercially viable. In the 1960s, MSU scientists developed cisplatin, a leading cancer fighting drug, and followed that work with the derivative, carboplatin. Albert Fert, an Adjunct professor at MSU, was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Physics together with Peter Grünberg.[96]

Today, Michigan State continues its research with facilities such as the U.S. Department of Energy-sponsored MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory[97] and a particle accelerator called the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory. The U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science named Michigan State University as the site for the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB). The $730 million facility will attract top researchers from around the world to conduct experiments in basic nuclear science, astrophysics, and applications of isotopes to other fields.[5]

In 2004, scientists at the Cyclotron produced and observed a new isotope of the element germanium, called Ge-60[98] In that same year, Michigan State, in consortium with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the government of Brazil, broke ground on the 4.1-meter Southern Astrophysical Research Telescope (SOAR) in the Andes Mountains of Chile. The consortium telescope will allow the Physics & Astronomy department to study galaxy formation and origins.[99] Since 1999, MSU has been part of a consortium called the Michigan Life Sciences Corridor, which aims to develop biotechnology research in the State of Michigan.[100] Finally, the College of Communication Arts and Sciences' Quello Center researches issues of information and communication management.

Endowment

MSU's (private, non-Morrill Act) endowment started in 1916 when the Engineering Building burned down. Automobile magnate R.E. Olds helped the program stay afloat with a gift of $100,000.[101] There was a time when MSU lagged behind peer institutions in terms of endowments. As recently as the early 1990s, MSU was last among the eleven Big Ten schools (of the time), with barely over $100 million in endowment funds.

This changed dramatically in the 2000s (decade), when the University started a campaign to increase the size of the endowment. At the close of fiscal year 2004–2005, the endowment had risen to $1.325 billion, raising the University to sixth of the 11 Big Ten schools in terms of endowment; within $2 million of the fifth-rated school.[102]

Colleges

MSU has over 200 academic programs offered by 17 degree-granting colleges.[5]

Residential colleges

MSU has several residential colleges, based on the Oxbridge "living-learning" model. By putting classes in student dormitories, these colleges improve student access to faculty and facilities. MSU's first residential college, Justin Morrill College started in 1965 with an interdisciplinary curriculum.[103] MSU closed Morrill College in 1979, but today the university has three residential colleges, including the recent opening of the Residential College in Arts & Humanities (RCAH) located in Snyder and Phillips halls.

Established in 1967, James Madison College is a smaller component residential college featuring multidisciplinary programs in the social sciences, founded on a model of liberal education. James Madison College is housed in Case Hall. Classes in the college are small, with an average of 25 students, and most instructors are tenure track faculty. James Madison College has about 1150 students total, with each freshman class containing about 320 students.[104] Each of Madison's four majors—Social Relations and Policy, International Relations, Political Theory and Constitutional Democracy, and Comparative Cultures and Politics[105]—requires two years of foreign language and one semester of "field experience" in an internship or study abroad program. Although Madison students make up about 4% of MSU graduates, they represent around 35% of the MSU's Phi Beta Kappa members.[106]

Also established in 1967, Lyman Briggs College teaches math and science within social, historical and philosophical contexts.[107] Many Lyman Briggs students intend to pursue careers in medicine, but the school supports over 30 coordinate majors, from human biology to computer sciences.[108] Lyman Briggs is one of the few colleges that lets undergraduates teach as "Learning Assistants."[109]

MSU's newest residential college is the Residential College in Arts & Humanities. Founded October 21, 2005,[110] the college provides around 600 undergraduates with an individualized curriculum in the liberal, visual and performing arts. Though all the students will graduate with the same degree, MSU encourages students in the college to get a second degree or specialization.[111] The university houses the new college in a newly renovated Snyder-Phillips Hall, the location of MSU's first residential college, Justin Morrill College.[112]

Professional schools

The Michigan State University College of Law is an independent, non-profit corporation[113] affiliated[114] with the public institution. Founded in Detroit in 1891 as the Detroit College of Law, the law school moved to East Lansing in 1995 becoming affiliated with the university. Students attending MSU College of Law come from 42 states and 13 countries. The law school publishes the Michigan State Law Review,[115] the Michigan State Journal of International Law, the Journal of Medicine Law, and the Journal of Business & Securities Law. The College of Law is the home of the Geoffrey Fieger Trial Practice Institute,[116] the first trial practice institute in the United States. In October 2018, MSU's Board of Trustees voted to fully integrate the College of Law into the university, thereby converting it from a private to a public law school. The integration is expected to take a year and a half to finalize.[117]

The Eli Broad College of Business has programs in accounting, information systems, finance, general management, human resource management, marketing, supply chain management, and hospitality business. The school has 2,066 admitted undergraduate students and 817 graduate students.[118] The Eli Broad Graduate School of Management, which Businessweek magazine in 2012 ranked 35th in the nation and 14th among public institutions,[119] offers three MBA programs, as well as joint degrees with the College of Law.[120] The opening of the Eugene C. Eppley Center for Graduate Studies in Hotel, Restaurant and Institutional Management brought the first program in the United States to offer a Master of Business Administration degree in Hotel, Restaurant and Institutional Management to MSU.[121]

The Michigan State University College of Nursing grants B.S.N., M.S.N., and PhD degrees.

The Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine was the world's first publicly funded college of osteopathic medicine.[122] It has a long-standing tradition of retaining its alumni in Michigan to practice – more than two-thirds of the college's graduates remain to practice in Michigan.[123] In 2008, the Michigan State University Board of Trustees approved a resolution endorsing the expansion of the College of Osteopathic Medicine to two sites in southeast Michigan, a move board members and college officials say will not only improve medical education in the state, but also address a projected physician shortage.[124]

According to U.S. News & World Report's 2016 rankings, the College of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O. degree) ranked tied for 12th among U.S. medical schools for primary care,[125] and the College of Human Medicine (MD degree) was ranked 70th among the U.S. medical schools for primary care.[126]

The College of Human Medicine graduates students with a Doctor of Medicine (M.D. degree) and is split into seven distinct campuses located in East Lansing, Kalamazoo, Flint, Saginaw, Marquette, Traverse City and Grand Rapids. Each campus is affiliated with local hospitals and other medical facilities professionals in the area.[127] For example, the Lansing campus includes Sparrow Hospital and McLaren–Greater Lansing Hospital.[128] The College of Human Medicine has recently gained attention for its expansion into the Grand Rapids area, with the new Secchia Center completed in the Fall of 2010, that is expected to fuel the growing medical industry in that region.[129]

Though Michigan State has offered courses in veterinary science since its founding, the College of Veterinary Medicine was not formally established as a four-year, degree-granting program until 1910.[130] In 2011, the Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine was ranked No. 9 in the nation.[131] The college has over 170,000 square feet (16,000 m2) of office, teaching, and research space, as well as a veterinary teaching hospital.[132]

Other academic units

In recent years, MSU's music program has grown substantially. Music major enrollment increased more than 97% between 1991 and 2004.[133] In early 2007, this growth led the university board of trustees to spin the music program off into its own college unit: The MSU College of Music.[134] The new college faces many new challenges, such as working with limited space[135] and funding.[136] Nevertheless, MSU's music college plans on continued success, placing an annual average of 25 graduate students in tenure stream university positions.[133]

The College of Education at Michigan State University offers graduate and undergraduate degrees in several fields, including counseling, educational psychology, special education, teacher education and kinesiology.[137] The graduate school has several programs ranked in the top five in the country by U.S. News & World Report for 2016: elementary teacher education (1st), secondary teacher education (1st), curriculum and instruction (3rd), educational psychology (4th), and higher education administration (4th).[90] The College of Education is housed in Erickson Hall.

Founded in 1956, the MSU Honors College provides individualized curricula to MSU's top undergraduate students. Though the college offers no majors of its own, it has its own dean and academic advisers to help Honors students with their educational pursuits. High school students starting at MSU may join the Honors College if they are in the top 5% of their high school graduating class and have an ACT score of at least 30 or an SAT total score of at least 1360.[138] Students can also be admitted after their first semester, generally if they're in the top 10% of their College in GPA. Once admitted, students must maintain a 3.20 GPA and complete eight approved honors courses to graduate with Honors College designation on their degree. If membership is relinquished, it cannot be reclaimed.[139]

After three years of planning, The College of Engineering launched the first stages of its Residential Experience for Spartan Engineering, formally known as the Residential Option for Scientists and Engineers (ROSES), the new program is in Wilson Hall after being housed in Bailey Hall for a number of years. The Residential program essentially combines with a brand new academic component, Cornerstone Engineering, where freshman engineering students not only get an overview of the engineering field(s) but get a hands-on experience along with it.[140] Global Engineering is a new subject that is of interest for not only the Cornerstone Engineering and Residential Experience programs but the entire College of Engineering at MSU. Engineering in today's society has shown to have a monumental impact on the global economy due to advancements in education, interdependence on economics with infrastructure, computers, transportation, technology and other manufactured goods as well as Michigan State University's study-abroad program being ranked No. 1 in the nation, allowing for students to experience education and learn cultures in hundreds of countries.[141] The newly established Cornerstone Engineering and Residential Experience programs for College of Engineering have started programs abroad for more courses in engineering including Study abroad seminars.[142] In 2014, the Detroit Free Press reported on a MSU study which ranked engineering among the top 20 college degrees with the highest starting salaries.[143]

MSU offers a 30 credit graduate program for Masters in Educational Technology[144] in 3 different formats; completely online,[145] hybrid[146] in East Lansing, Michigan, or overseas.

Athletics

Michigan State's NCAA Division I-A program offers 12 varsity sports for men and 13 for women.[5] Since their teams are called the Spartans, MSU's mascot is a Spartan warrior named Sparty. The university participates in the Big Ten Conference in all varsity sports, including the new Big Ten hockey conference, featuring 6 teams. The current athletic director is Bill Beekman who replaced Mark Hollis. Bill Beekman officially assumed the role of MSU's 19th athletic director on July 17, 2018. He was appointed interim athletic director on Feb. 5, 2018, before taking over the position full-time on July 17, 2018.[147] Hollis was promoted to the position on January 1, 2008.[148] Hollis replaced Ron Mason, who served as head hockey coach from 1979 to 2002, retiring with a record total of 924 wins, and a 635–270–69 record at MSU.[149]

In 1888 Michigan State University (then known as Michigan Agricultural College) along with Olivet, Albion and Hillsdale Colleges was a founding member of the nation's oldest athletic conference, the Michigan Intercollegiate Athletic Association (MIAA). MAC left the conference in 1907.

Football

Football has a long tradition at Michigan State. Starting as a club sport in 1884, football gained varsity status in 1896.[150] MSU football teams won the Rose Bowl in 1954, 1956, 1988, and 2014. They won national championships in 1951, 1952, 1955, 1957, 1965 and 1966. The Spartans accounted for four of the top eight selections in the 1967 NFL Draft, the only time a college football program has accomplished such a feat.

Today, the football team competes in Spartan Stadium, a renovated 75,005 seat football stadium near the center of campus. The current coach is Mel Tucker, the new head coach after Mark Dantonio left.[151] Mark Dantonio

led the team in its first season to a 7–6 record. In 2010, the Spartans finished 11–2 (7–1 in conference play) and were Co-Big Ten Champion along with Wisconsin and Ohio State. In 2011, the Spartans finished 1st in the Legends Division of the Big Ten with a 7–1 (11–3) conference record, logging back-to-back 11 win seasons for the first time in Spartan history. In 2014, MSU achieved an 11–2 overall record with losses only to the University of Oregon Ducks and The Ohio State Buckeyes, and ended the season ranked #5.

MSU's traditional archrival is the University of Michigan, against whom they compete annually for the Paul Bunyan Trophy. Their overall record against the Wolverines currently stands at 32–67–5 and 23–34–2 since 1953 when the Paul Bunyan Trophy was established and MSU joined the Big Ten Conference.

Men's basketball

MSU's men's basketball team has won the National Championship twice: in 1979 and again in 2000.[152] In 1979, Earvin "Magic" Johnson,[153] along with Greg Kelser[154] and Jay Vincent[155] led MSU to a 75–64 win against the Larry Bird-led Indiana State Sycamores in the Championship game. In 2000, three players from Flint, Morris Peterson,[156] Charlie Bell[157] and Mateen Cleaves,[158] led the team to its second national title. Dubbed the "Flintstones", they were the key to the Spartans' victory over Florida in the Championship game. In 2009 the Spartans made it to the National Championship game before losing 89–72 to North Carolina.

The basketball team plays at the Jack Breslin Student Events Center under head coach Tom Izzo, who has a 603–231 record as of March 22, 2019 ( .723 winning percentage). The student spirit section at Breslin is called the Izzone. Izzo's coaching has helped the team make seven Final Fours since 1999, winning the title in 2000, and eighteen consecutive NCAA tournament appearances (beginning in 1998).

On December 13, 2003, Michigan State and Kentucky played in the Basketbowl, in which a record crowd of 78,129 watched the game in Detroit's Ford Field. Kentucky won 79–74.[159]

Men's ice hockey

The Michigan State University men's ice hockey team started in 1924, though it has been a varsity sport only since 1950. The team has since won national titles in 1966, 1986 and 2007. The Spartans came close to repeating the national title in 1987, but lost the championship game to the University of North Dakota. They play at MSU's Munn Ice Arena. Former head coach Ron Mason is college hockey's winningest coach with 924 wins total and 635 at MSU.[149] The current head coach is Tom Anastos. The MSU men's ice hockey team competes in the Big Ten conference. They formerly competed in the Central Collegiate Hockey Association. Michigan State leads the CCHA in all-time wins, is second in CCHA Conference championships with 7, and is first in CCHA Tournament Championships with 11. Along with the University of Michigan (U-M) and the Ohio State University, it was one of three Big Ten schools in the CCHA. As with other sports, the hockey rivalry between MSU and U-M is a fierce one, and on October 6, 2001, MSU faced U-M in the Cold War, during which a world record crowd of 74,554 packed Spartan Stadium to watch the game end in a 3–3 tie.[160] In the 2006–2007 season, the Men's Ice Hockey team defeated Boston College for its third NCAA hockey championship.[161]

Men's cross country

Between World War I and World War II, Michigan State College competed in the Central Collegiate Conference, winning titles in 1926–1929, 1932, 1933 and 1935. Michigan State also experienced success in the IC4A, at New York's Van Cortlandt Park, winning 15 team titles (1933–1937, 1949, 1953, 1956–1960, 1962, 1963 and 1968). Since entering the Big Ten in 1950, Michigan State has won 14 men's team titles (1951–1953, 1955–1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1970 and 1971). Michigan State hosted the inaugural NCAA cross country championships in 1938 and every year thereafter through 1964 (there was no championship in 1943). The Spartans won NCAA championships in 1939, 1948, 1949, 1952, 1955, 1956, 1958 and 1959.[162][163][164]

Wrestling

MSU Spartan Wrestling won their only team NCAA Championship in 1967. The current Spartans Head coach is Roger Chandler in his 2nd season. The team competes on campus at the Jenison Field House. Spartan Wrestling has over 50 Big Ten Conference Champions, over 100 All-Americans, and 11 individual wrestlers have NCAA Division I Wrestling Championships. Notable former Spartan wrestlers include Rashad Evans and Gray Maynard.

Student life

East Lansing is very much a college town, with 60.2% of the population between the ages of 15 and 24.[165] President John A. Hannah's push to expand in the 1950s and 1960s resulted in the largest residence hall system in the United States.[166] Around 16,000 students live in MSU's 23 undergraduate halls, one graduate hall, and three apartment villages. Each residence hall has its own hall government, with representatives in the Residence Halls Association. Yet despite the size and extent of on-campus housing, the residence halls are complemented by a variety of housing options. 58% of students live off-campus,[167] mostly in the areas closest to campus, in either apartment buildings, former single-family homes, fraternity and sorority houses, or in a co-op.

In 2014 there were approximately 50,085 students, 38,786 undergraduate and 11,299 graduate and professional. The students are from all 50 states and 130 countries around the world.[168]

Greek life

With over 3,000 members, Michigan State University's Greek Community is one of the largest in the US. Started in 1872[169] and re-established in 1922 by Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity, Alpha Gamma Rho fraternity, and Alpha Phi sorority; the MSU Greek system now consists of 55 Greek lettered student societies.[170] These chapters are in turn under the jurisdiction of one of MSU's four Greek governing councils: National Panhellenic Conference, North American Interfraternity Council, National Pan-Hellenic Council,[171] and Independent Greek Council. National Pan-Hellenic Council is made up of 9 organizations, 5 Fraternities and 4 Sororities, that were founded on Historically Black College and Universities (HBCU's).[172] The Interfraternity Council and the Women's Panhellenic Council are each entirely responsible for their own budgets, giving them the freedom to hold large fundraising and recruitment events. MSU's fraternities and sororities hold many philanthropy events and community fundraisers. For example, in April 2011 the Greek Community held Greek Week to raise over $260,000 for the American Cancer Society, and $5,000 for each of these charities: Big Brothers Big Sisters, The Listening Ear and previous charities include: the Make-a-Wish Foundation (MSU Chapter), Share Laura's Hope, The Mary Beth Knox Scholarship, and the Special Olympics, in which fraternity and sorority members get to help each other participate.[173]

Student organizations

The Associated Students of Michigan State University (ASMSU) is the all-university undergraduate student government of Michigan State University.[174] It is unusual amongst university student governments for its decentralized bicameral structure,[175] and the relatively non-existent influence of the Greek system. The structure has since changed to a single General Assembly as part of reorganization in the late 2000s. ASMSU representatives are nonpartisan and many are elected in noncompetitive races. Their mission is to enhance the individual and collective student experience through education, empowerment, and advocacy by education to the needs and interest of students. Some services they offer include: free blue books, low cost copies and printing, free yearbooks, interest free loans, funding for student organizations, free legal consultation, and iClicker and graphing calculator rentals.

Students pay $21 per semester to fund the functions of the ASMSU, including stipends for the organization's officers and activities throughout the year.[176] Some students have criticized ASMSU for not having enough electoral participation to gain a student mandate. Turnout since 2001 has hovered between 3 and 17 percent, with the 2006 election bringing out 8% of the undergraduate student body.[177]

Student-run organizations beyond student government also have a large impact on the East Lansing/Michigan State University community. Student Organizations are registered through the Department of Student Life, which currently has a registry of over 800 student organizations.[178]

The Eli Broad College of Business includes 27 student organizations of primary interest to business students. The three largest organizations are the Finance Association (FA), the Accounting Student Association (ASA), and the Supply Chain Management Association (SCMA).[179] The SCMA is the host of the university's largest major specific career fair. The fair attracts over 100 companies and over 400 students each year.[180]

Activism

Activists have played a significant role in MSU history. During the height of the Vietnam War, student protests helped create co-ed residence halls, and blocked the routing of Interstate 496 through campus.[181] In the 1980s, Michigan State students convinced the University to divest the stocks of companies doing business in apartheid South Africa from its endowment portfolio, such as Coca-Cola.[182] MSU has many student groups focused on political change. Graduate campus groups include the Graduate Employees Union[183] and the Council of Graduate Students.[184] Michigan State also has a variety of partisan groups ranging from liberal to conservative, including the College Republicans, the College Democrats and several third party organizations. Other partisan activist groups include Young Americans for Freedom and Young Americans for Liberty on the right; Young Democratic Socialists, Students for Economic Justice, Young Communist League and MEChA on the left. Given MSU's proximity to the Michigan state capital of Lansing, many politically inclined Spartans intern for state representatives.

Sustainability

The MSU Office of Sustainability works with the University Committee for a Sustainable Campus to "foster a collaborative learning culture that leads the community to heightened awareness of its environmental impact."[185] The University is a member of the Chicago Climate Exchange, the world's first greenhouse gas emission registry, and boasts the lowest electrical consumption per square foot among Big Ten universities. The University has set a goal of reducing energy use by 15%, reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 15%, reducing landfill waste by 30% by 2015.[186]

The university has also pledged to meet LEED-certification standards for all new construction. In July 2009, the University completed construction of a $13.3 million recycling center, and hopes to double their 2008 recycling rate of 14% by 2010.[187] The construction of Brody Hall, a residence hall of Michigan State University Housing, was completed in August 2011 and qualified for LEED Silver certification because the facility includes a rain water collection tank used for restroom fixtures, a white PVC roof, meters that will monitor utilities to make sure they are used efficiently, and the use of recycled matter and local sources for building materials.[188]

The Environmental Steward's program support's president Simon's "Boldness by Design" strategic vision to transform environmental stewardship on campus within the seven-year time frame.[189] Environmental stewards promote environmental changes among co-workers and peers, be points of contact for their department for environment-related concerns, and be liaisons between the Be Spartan Green Team and buildings.[189]

The Student Organic Farm is a student-run, four-season farm, which teaches the principals of organic farming and through a certificate program and community-supported agriculture (CSA) on ten acres on the MSU campus.[190] The certificate program consists of year-round crop production, course work in organic farming, practical training and management, and an off-site internship requirement.[191]

Media

MSU has a variety of campus media outlets. The student-run newspaper is The State News and free copies are available online or at East Lansing newsstands. The paper prints 28,500 copies from Monday through Friday during the fall and spring semesters, and 15,000 copies Monday through Friday during the summer.[192] The paper is not published on weekends, holidays, or semester breaks, but is continually updated online at statenews.com. The campus yearbook is called the Red Cedar Log.[193] Red Cedar Review, Michigan State University's premier literary digest for over forty years, is the longest running undergraduate-run literary journal in the United States.[194] It is published annually by the Michigan State University Press.

MSU also publishes a student-run magazine during the academic year called Ing Magazine.[195] Created in 2007 by MSU alumnus Adam Grant, the publication is released at the beginning of each month and publishes 7 issues each school year.[196] MSU also publishes a student-run fashion and lifestyle magazine called VIM Magazine once a semester.

Electronic media include three radio stations and one public television station, as well as student-produced television shows. MSU's Public Broadcasting Service affiliate, WKAR-TV, the station is the second-oldest educational television station in the United States, and the oldest east of the Mississippi River. Besides broadcasting PBS shows, WKAR-TV produces its own local programming, such as a high school quiz bowl show called "QuizBusters". In addition, MSU has three radio stations; WKAR-AM plays National Public Radio's talk radio programming, whereas WKAR-FM focuses mostly on classical music programming.[197] Michigan State's student-run radio station, WDBM, broadcasts mostly alternative music during weekdays and electric music programming nights and weekends.[198]

Alumni

19th century

Important College leaders in the 19th century include John C. Holmes, who kept the Agriculture School from being a part of the University of Michigan and is widely credited with being the prime mover for the school's founding;[15] Joseph R. Williams, the first president,[17] and Theophilus C. Abbot, the third president who stabilized the College after the Civil War, were both key in establishing and maintaining the college's early balanced liberal/practical curriculum.[199] Also of importance was botany professor William J. Beal, an early plant (hybrid corn) pre-geneticist who championed the laboratory teaching method.[200] Another distinguished faculty member of the era was the alumnus/professor Liberty Hyde Bailey.[201] Bailey was the first to raise the study of horticulture to a science, paralleling botany, which earned him the title of "Father of American Horticulture".[202] William L. Carpenter, a jurist who was elected to the Third Judicial Circuit of Michigan in 1894, and member of the Michigan Supreme Court from 1902 until 1904. Other famous 19th-century graduates include Ray Stannard Baker,[203] a famed "muckraker" journalist and Pulitzer Prize winning biographer; Minakata Kumagusu,[204] a renowned environmental scientist; William Chandler Bagley, a pioneering education reformer;[205] and Lyman J. Briggs, 1893 graduate and renowned engineer and physicist who was the chairman of the U.S. Uranium Committee before the Second World War.

20th and 21st centuries

As of fall 2018, there were about 634,300 living MSU alumni worldwide.[5] Notable politicians and public servants from MSU include current governor of Michigan Gretchen Whitmer, former Michigan governors James Blanchard[206] and John Engler,[207] U.S. Senators Debbie Stabenow,[208] Tim Johnson, and Spencer Abraham, (who also served as Secretary of Energy),;[209] U.S. Ambassador to Brazil Donna Hrinak, former Prime Minister of South Korea Lee Wan-koo, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Director Richard Cordray, former Jordan prime minister Adnan Badran, and Chief Justice of the Texas Supreme Court Wallace B. Jefferson.[210]

Trial lawyer Geoffrey Feiger, billionaire philanthropists Tom Gores, Andrew Beal and Eli Broad,[211] Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Richard Ford, Teamsters president James P. Hoffa,[212] and Quicken Loans founder and billionaire Cleveland Cavaliers owner Dan Gilbert,[213] are all also MSU alums.

Alumni in Hollywood include actors such as James Caan, Anthony Heald,[214] Robert Urich[215] and William Fawcett;[216] comedian Dick Martin, voice actor SungWon Cho, comedian Jackie Martling, film directors Michael Cimino and Sam Raimi, and film editor Bob Murawski,[217] as well as screenwriter David Magee[218] Puerto Rican comedian Sunshine Logroño (who has played the occasional Hollywood movie) was a graduate student at MSU.

Composer Dika Newlin received her undergraduate degree from MSU,[219] while lyricist, theatrical director and clinical psychologist Jacques Levy earned a doctorate in psychology.[220] The university has also produced such jazz luminaries as pianist Henry Butler,[221] vibraphonist Milt Jackson,[222] and keyboardist/composer-arranger Clare Fischer.[223]

Journalists include NBC reporter Chris Hansen,[224] AP White House correspondent Nedra Pickler and NPR Washington correspondent Don Gonyea. Novelist Michael Kimball graduated in 1990. Novelist and true crime author R. Barri Flowers, who in 1977 earned a bachelor's degree and in 1980 a master's degree in criminal justice, was inducted in 2006 into the MSU Criminal Justice Wall of Fame.[225] Author Erik Qualman graduated with honors in 1994 and was also Academic Big-Ten in basketball. Susan K. Avery, the first woman president and director of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, received an MSU bachelor's degree in physics.[226] In addition, two of the Little Rock Nine attended Michigan State, including Ernest Green,[227] the first black student to graduate from Little Rock Central High School, and Carlotta Walls LaNier.[228] The University awarded an honorary degree to Robert Mugabe in 1990, but revoked it in 2008.[229]

Spartans have made their mark in all major American sports. MSU alumni formerly or currently in the NBA include point guard and three-time MVP Earvin "Magic" Johnson,[153] Greg Kelser,[154] Jay Vincent,[155] Steve Smith,[230] Scott Skiles,[231] Jason Richardson,[232] Zach Randolph,[233] Johnny Green, Draymond Green, Gary Harris, Denzel Valentine, Deyonta Davis, Bryn Forbes, Miles Bridges and Jaren Jackson Jr..

In the National Football League, MSU alumni include Carl Banks, who was a member of the Giants teams that won Super Bowls XXI and XXV and a member of the NFL's 1980's All-Decade Team; twenty-one year veteran quarterback Earl Morrall,[234] defensive end and actor Bubba Smith,[235] former Detroit Lions head coach Wayne Fontes,[236] NFL games-played leader Morten Andersen,[237] Plaxico Burress,[238] Andre Rison,[239] Derrick Mason,[240] Muhsin Muhammad,[241] T. J. Duckett,[242] Flozell Adams,[243] Julian Peterson,[244] Charles Rogers,[245] and Jim Miller.[246]

The American Football League's All-Time Team includes tight-end Fred Arbanas[247] and safety George Saimes.[248]

Former Michigan State players in the National Hockey League include All Star Defensemen Duncan Keith, Rod Brind'Amour,[249] Anson Carter,[250] Donald McSween,[251] Adam Hall,[252] John-Michael Liles, Justin Abdelkader, Corey Tropp, brothers Kelly Miller[253] and Kip Miller,[254] as well as their cousins, brothers Ryan Miller[255] and Drew Miller.[256]

Former Michigan State players in Major League Baseball include Hall of Fame inductee Robin Roberts,[257] Kirk Gibson,[258] Steve Garvey[259] and Mark Mulder.[260] Olympic gold medalists include Savatheda Fynes[261] and Fred Alderman.[262] The Spartans are also contributing athletes to Major League Soccer, as Doug DeMartin, Dave Hertel, Greg Janicki, Rauwshan McKenzie, Ryan McMahen, and Fatai Alashe have all played in Major League Soccer.[263] In addition, Alex Skotarek, Steve Twellman and Buzz Demling played in the North American Soccer League, with Demling playing in the 1972 Summer Olympics and the United States Men's National Soccer Team in the 1970s.

Ryan Riess, 2013 World Series of Poker Main Event Champion, is a 2012 graduate of MSU.[264] NCAA Gymnastics Champion and former Sesame Street Muppet performer Toby Towson is an MSU graduate.

Miss America 1961, Nancy Fleming, is a graduate of Michigan State.[265]

Verghese Kurien was an Indian social entrepreneur known as the "Father of the White Revolution" for his Operation Flood, the world's largest agricultural development programme. He earned a Master of Science in Metallurgical Engineering from Michigan State University in 1948. Peter Schmidt, an American economist and econometrician, is both an alumnus (1970) and faculty member of MSU, holding a University Distinguished Professor position since 1997.[266] Tyler Oakley, YouTube personality, graduated from Michigan State University in 2011.[267]

Vince Colella is a personal injury attorney in Southfield, MI. He has handled a number of high-profile cases. [268]

See also

References

- "Editorial Content for the MSU Brand". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "Go Tell the Spartans: Upload Your Video". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "Feature: The Campaign for MSU Advancing Knowledge, Transforming Lives". Michigan State University Alumni Association. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- As of June 30, 2019. "U.S. and Canadian 2019 NTSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2019 Endowment Market Value, and Percentage Change in Market Value from FY18 to FY19 (Revised)". National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- "MSU Facts". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "Color Palette – The MSU Brand". Michigan State University. September 1, 2015. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- Staley, David J. (January 2013). "Democratizing American Higher Education: The Legacy of the Morrill Land Grant Act". Origins. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015.

- Beal, W.J. (1915). History of the Michigan agricultural college and biographical sketches of trustees and professors. Agricultural College. Archived from the original on February 8, 2016.

- "Our Members". Association of American Universities. Archived from the original on April 5, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "State of Michigan" (PDF). Michigan Legislature. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ""Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)". College Football Data Warehouse. Accessed December 28, 2007."Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 20, 2007. Retrieved February 8, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Women's Cross Country Crowned 2019 Big Ten Champions". Michigan State Spartan Athletics. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "MSU Student-Athletes Post All-Time Highs for GSR and FGR". Michigan State Spartan Athletics. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "Michigan Constitution of 1850". Wikisource. Article 13, Section 11. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "Milestones of MSU's Sesquicentennial Archived August 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine". MSU University Archives and Historical Collection. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- Darling, Birt. (1950). City in the Forest; The Story of Lansing. New York: Stratford House. p. 121. LCCN 50008202.

- "Joseph R. Williams Biographical Information Archived September 16, 2006, at the Wayback Machine". MSU Archives and Historical Collection Accessed March 5, 2008.

- "The National Schools of Science", The Nation, p. 409, November 21, 1867, archived from the original on June 24, 2016

- Miller, Whitney. (2002). East Lansing: Collegeville Revisited (Images of America). Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 0-7385-2045-4.

- Heineman, Kenneth J. (1993). Campus Wars: The Peace Movement at American State Universities in the Vietnam Era. New York: New York University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-8147-3512-6.

- "It's Big 10 Now – Spartans Admitted". Wisconsin State Journal. May 21, 1949. p. 13.

- Kuhn, Madison. (1955). Michigan State: The First Hundred Years, 1855–1955. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. p. 471. ISBN 0-87013-222-9.

- "Michigan.gov". Michigan.gov. Archived from the original on November 15, 2010. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- "Oakland's History". Oakland University. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012.

- Darrow, Bob. Simon: MSU to be model university Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The State News. September 9, 2005. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "MSU, U-M, Wayne State create University Research Corridor". MSU News. Archived from the original on September 1, 2011. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- "U.S. Department of Education Releases List of Higher Education Institutions with Open Title IX Sexual Violence Investigations". U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- Associated Press (May 1, 2014). "UM and MSU among 55 Colleges in Federal Sexual Abuse Investigation". Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- Smith, Brian (February 28, 2014). "Michigan State sexual assault investigation tied to a 2010 incident, spokesman confirms". Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- USA TODAY Sports (January 24, 2018). "Watch: Nassar victim Rachael Denhollander speaks out". Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2018 – via YouTube.

- Kozlowski, Kim (January 18, 2018). "What MSU knew: 14 were warned of Nassar abuse". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on January 20, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- "Michigan State President Resigns; US Olympic Committee Face Fallout of Larry Nassar Sentencing". NBC Chicago. January 24, 2018. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018.

- Pearce, Matt (January 24, 2018). "Michigan State University president resigns amid widening calls for accountability over Larry Nassar abuse scandal". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018.

- Levenson, Eric (January 15, 2018). "Larry Nassar's sexual abuse victims finally get their days in court". CNN. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018.

- Maese, Rick; Hobson, Will (February 16, 2017). "USA Gymnastics alerted FBI in 2015 to doctor accused of abuse". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018.

- Macur, Juliet (September 13, 2016). "Sexual Abuse Charges Put Shadow on U.S. Gymnastics Federation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017.

- "ABC Sports News". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- Haag, Matthew; Tracy, Marc (January 24, 2018). "Michigan State President Lou Anna Simon Resigns Amid Nassar Fallout". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018.

- Tracy, Marc (January 26, 2018). "Michigan State Athletic Director Mark Hollis Resigns". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018.

- "William Strampel, former Michigan State University Dean, accused of storing nude photos". CBS News. March 27, 2018. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- Smith, Mitch (November 20, 2018). "Ex-President of Michigan State Charged with Lying about Nassar Case". NYT.com. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- Kozlowski, Kim (January 28, 2019). "How John Engler's MSU reign fell apart". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on March 20, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- "Saints' Rest: Early Campus Life at MSU". Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved June 13, 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) Michigan State University. Retrieved on March 5, 2008.

- "Building Data Summary Archived April 27, 2015, at the Wayback Machine". MSU Physical Plant. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- "Frequently Asked Questions Archived January 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". MSU Resource Center for Persons with Disabilities (RCPD). Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "Land Management Office Archived June 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine". Michigan State University Land Management Office. August 29, 2005. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- Bruns, Adam (January 2009).How Are You Helping Companies Grow? Archived April 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.Site Selection Magazine. Retrieved on December 27, 2009.

- "Carport Solar Array Receives 2018 Innovative Project Award". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "Campus sustainability information". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "MSU'S SOLAR CARPORT RECEIVES THE SMART ENERGY DECISIONS ONSITE RENEWABLE ENERGY AWARD". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- Forsyth, Kevin S. (2003). "Michigan Agricultural College – Introduction". A Brief History of East Lansing, Michigan. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- Stanford, Linda O. (2002). MSU Campus: Buildings, Places, Spaces. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. p. 60. ISBN 0-87013-631-3.

- Roeschke, Jaclyn. "Former 'U' president immortalized with bronze statue Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". The State News. September 20, 2004. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "MSU Museum – About the Museum". Retrieved February 25, 2009. Archived October 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "2020 Vision Campus Master Plan Archived June 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine". MSU Campus Planning and Administration. 2006. Accessed March 5, 2008."Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 17, 2007. Retrieved February 8, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Stanford, Linda (2002). MSU Campus: Buildings, Places, Spaces. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-631-3.

- "Building for Tomorrow". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "Facilities". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on April 1, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "About the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "Kellogg Hotel and Conference Center". Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 28, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) MSU Dubai

- Jason Lane and Kevin Kinser "A Phoenix Rising in the Desert: Michigan State University" The Chronicle of Higher Education July 31, 2012 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- About Michigan State University Dubai Archived June 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Andrew Mills "Low Enrollment Led Michigan State U. to Cancel Most Programs in Dubai" The Chronicle of Higher Education July 6, 2010 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 16, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Larry Abrahamson "Michigan State To Close Dubai Campus" July 6, 2010. npr. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 28, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Michigan State University". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- "Common Data Set 2018-2019, Part C" (PDF). Michigan State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- "Applications increase, MSU welcomes largest class after using Common Application". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on September 6, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "Fall, 2019 Enrollment Report" (PDF). Michigan State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "10 Colleges With the Most Undergraduates". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ['"Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)]'Office of the Registrar'.' Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Office of the Registrar Enrollment and Term End Reports". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Ruiz, Neil. "The Geography of Foreign Students in U.S. Higher Education: Origins and Destinations". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on November 23, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Wolcott, RJ. "For years, Chinese students flocked to MSU. Now their numbers are declining". 17 May 2018. Lansing State Journal. Archived from the original on May 29, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Greene, Howard R. & Greene, Matthew W. (2001). The Public Ivies: America’s Flagship Public Universities (1st ed.). New York: Cliff Street Books. ISBN 0-06-093459-X.

- "America’s longest-operating Office of the Ombudsman turns 40 Archived September 25, 2007, at the Wayback Machine". Michigan State University Newsroom. September 19, 2007. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- "Enrollment Trends & Statistics". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on April 19, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "Studies in Antarctic System Science—Antarctica Archived June 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine". MSU Office of Study Abroad. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2019: USA". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- "America's Top Colleges 2019". Forbes. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- "U.S. College Rankings 2020". Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- "Best Colleges 2020: National University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- "2019 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2019". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- "QS World University Rankings® 2021". Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- "World University Rankings 2020". THE Education Ltd. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "Best Global Universities Rankings: 2020". U.S. News & World Report LP. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- "Michigan State University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "QS World University Rankings". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "U.S. News Best Colleges Rankings: Michigan State University". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on May 31, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "U.S. B-Schools Ranking". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on April 19, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "Ph.D. in Accounting". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on April 1, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "#27 Broad College of Business". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 9, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "Distinctions for College of Communication Arts and Sciences". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on August 31, 2011. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- "ARL Statistics 2007–2008 — Rank Order By Volumes Held Archived January 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine". Association of Research Libraries. Accessed June 20, 2010.

- Thoel, Tara. "Adjunct physics professor at MSU wins Nobel Prize Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". The State News. October 9, 2007. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- "Michigan State University | College of Natural Science | Plant Research Laboratory". Prl.msu.edu. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- "First observation of Germanium-60 and Selenium-64 Archived August 10, 2014, at the Wayback Machine". NSCL Science Nuggets. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- "Points of Pride". MSU Today. Accessed March 5, 2008. Archived May 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Truscott, John. "Governor Signs Bill Creating 'Life Sciences Corridor' in Michigan Archived May 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine". Michigan Executive Office press release. July 19, 1999. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- Rodriguez, Michael (2004). R.E. Olds and Industrial Lansing. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 117. ISBN 0-7385-3272-X.

- Seguin, Rick. "Endowment surges in growth, rankings Archived September 2, 2006, at the Wayback Machine". MSU News Bulletin. 2006. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "Unofficial website Archived February 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". Justin Morrill College. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- ""Quick Madison Facts"". Archived from the original on June 27, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). James Madison College @ Michigan State University. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ""You and JMC"". Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved August 14, 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). James Madison College @ Michigan State University. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ""Quick Madison Facts"". Archived from the original on October 20, 2007. Retrieved October 20, 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). James Madison College @ Michigan State University. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "Educational Philosophy Archived June 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine". Lyman Briggs College. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "Majors". Lyman Briggs College. Retrieved June 18, 2010. Archived January 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "Undergraduate Learning Assistant Application 2008–2009 Archived April 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). Lyman Briggs College. Accessed March 5, 2008."Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Collins, Laura. "Trustees approve residential college Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". The State News. October 24, 2005. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "How the Program Works Archived July 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine". Michigan State University Residential College in Arts & Humanities. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- "Living in the College Archived July 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine". Michigan State University Residential College in Arts & Humanities. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "Board of Trustees". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011.

- "MSU Law: News". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011.

- "Main Page Archived June 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine". Michigan State Law Review. Accessed March 5, 2008."Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 2, 2007. Retrieved February 8, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)