French ironclad Vauban

Vauban was the lead ship of the Vauban class of ironclad barbette ships built for the French Navy in the late 1870s and 1880s. Intended for service in the French colonial empire, she was designed as a "station ironclad", smaller versions of the first-rate vessels built for the main fleet. The Vauban class was a scaled down variant of Amiral Duperré. They carried their main battery of four 240 mm (9.4 in) guns in open barbettes, two forward side-by-side and the other two aft on the nautical. Vauban was laid down in 1879 and was completed in 1885.

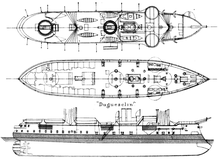

Vauban as originally completed | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Vauban |

| Builder: | Arsenal of Cherbourg |

| Laid down: | February 1879 |

| Launched: | July 1882 |

| Commissioned: | 1885 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 6,112 long tons (6,210 t) |

| Length: | 81 m (265 ft 9 in) lwl |

| Beam: | 17.45 m (57 ft) |

| Draft: | 7.62 to 7.7 m (25 ft 0 in to 25 ft 3 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 14 to 14.5 kn (25.9 to 26.9 km/h; 16.1 to 16.7 mph) |

| Crew: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

Though Vauban had been intended for use overseas, she spent the majority of her career in French waters in the Mediterranean Squadron. During this period, she was primarily occupied with annual training exercises. By 1893, she was reduced to the Reserve Division. She was sent to French Indochina in 1899, though she was relieved in 1900. Her return to France proved to be short-lived, as the Boxer Rebellion in Qing China prompted the French to send reinforcements to help suppress the rebellion. Vauban spent the next four years in East Asia, though she spent 1903 and 1904 in reserve in Saigon. She was struck from the naval register in 1905, though her ultimate fate is unknown.

Design

The Vauban class of barbette ships was designed in the late 1870s as part of a naval construction program that began under the post-Franco-Prussian War fleet plan of 1872. At the time, the French Navy categorized its capital ships as high-seas ships for the main fleet, station ironclads for use in the French colonial empire, and smaller coastal defense ships. The Vauban class was intended to serve in the second role, and they were based on the high-seas ironclad Amiral Duperré, albeit a scaled-down version.[1]

Vauban was 81 m (265 ft 9 in) long at the waterline, with a beam of 17.45 m (57 ft) and a draft of 7.62 to 7.7 m (25 ft 0 in to 25 ft 3 in). She displaced 6,112 long tons (6,210 t). She was fitted with a pair of pole masts equipped with spotting tops for her main battery guns. The crew numbered 24 officers and 450 enlisted men. Her propulsion machinery consisted of two compound steam engines that drove a pair of screw propellers, with steam provided by eight coal-burning fire-tube boilers. Her engines were rated to produce 4,400 indicated horsepower (3,300 kW) for a top speed of 14 to 14.5 knots (25.9 to 26.9 km/h; 16.1 to 16.7 mph).[2][3] On steam trials, Vauban reached 14.3 knots (26.5 km/h; 16.5 mph) using forced draft.[4] To supplement the steam engines, she was fitted with a brig sail rig with a total area of 2,160 m2 (23,200 sq ft).[2]

Her main battery consisted of four 240 mm (9.4 in), 19-caliber guns mounted in individual barbette mounts, two forward placed abreast and two aft, both on the centerline. She carried a 190 mm (7.6 in) gun in the bow as a chase gun. These guns were supported by a secondary battery of six 140 mm (5.5 in) guns carried in a central battery located amidships in the hull, three guns per broadside. For defense against torpedo boats, she carried four 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss revolver cannon and twelve 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder Hotchkiss revolvers, all in individual mounts. Her armament was rounded out with two 356 mm (14 in) torpedo tubes in above-water launchers. The ship was protected with wrought iron armor; her belt was 152 to 254 mm (6 to 10 in) thick and extended for the entire length of the hull. The barbettes for the main battery were 203 mm (8 in) thick.[2]

Service history

.jpg)

Vauban was built in the Arsenal of Cherbourg, and her keel was laid down in October 1877,[3] or February 1879. She was launched in July 1882 and was completed in 1885.[2] The ship took part in the annual large-scale fleet maneuvers with the Mediterranean Squadron in 1886, which were held off Toulon from 10 to 17 May. The exercises were used to test the effectiveness of torpedo boats in defending the coastline from a squadron of ironclads, whether cruisers and torpedo boats could break through a blockade of ironclads, and whether a flotilla of torpedo boats could intercept ironclads at sea.[5]

Vauban served in the 3rd Division of the Mediterranean Squadron in 1890 as the flagship of Rear Admiral O'Neill, along with her sister ship Duguesclin and the ironclad Bayard. She took part in the annual fleet maneuvers that year in company with her division-mates and six other ironclads, along with numerous smaller craft. Vauban served as part of the simulated enemy force during the maneuvers, which lasted from 30 June to 6 July.[6] During the 1890 fleet maneuvers, the ship was transferred to the 4th Division of the 2nd Squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet, along with Duguesclin and Bayard. The ships concentrated off Oran, French Algeria on 22 June and then proceeded to Brest, France, arriving there on 2 July for combined operations with the ships of the Northern Squadron. The exercises began four days later and concluded on 25 July, after which Amiral Duperré and the rest of the Mediterranean Fleet returned to Toulon. During the maneuvers, a number of French ships suffered machinery problems, including Vauban, which had ball bearings in her propulsion system become overheated, forcing her to temporarily withdraw from operations.[7]

During the fleet maneuvers of 1891, which began on 23 June, Vauban served in the 3rd Division, once again with Duguesclin and Bayard. The maneuvers lasted until 11 July, during which the 3rd Division operated as part of the "French" fleet, opposing a simulated hostile force that attempted to attack the southern French coast.[8] By 1893, Vauban had been reduced to the Reserve Division of the Mediterranean Squadron, where she and Dueguesclin were rated as armored cruisers. While in reserve, the ships were kept in commission with full crews for six months of the year to take part in training exercises.[9] By 1895, the two Vauban-class ironclads had been removed from the Reserve Division altogether, and were no longer kept in service, their place having been taken by new, purpose-built armored cruisers.[10] They were reduced to the 2nd category of reserve, along with several old coastal defense ships and unprotected cruisers. The ships were retained in a state that allowed them to be mobilized in the event of a major war.[11]

In 1899, Vauban was recommissioned for service abroad, finally serving in the role for which she was built. She was deployed to French Indochina, along with the unprotected cruiser Duguay-Trouin and the protected cruisers Descartes and Pascal.[12] Vauban remained there for just a year before she was replaced by the new protected cruiser D'Entrecasteaux.[13] As the Boxer Rebellion in Qing China worsened in 1900, the French decided to reinforce the Far East squadron, sending Vauban, the ironclad Redoutable and the protected cruiser Guichen there by 1901.[14] Vauban had arrived in 1900, and she was approaching Nagasaki, Japan, in September, when a shell accidentally exploded in her forward magazine, wounding five men.[15] After the rebellion was suppressed, the Navy determined Vauban was no longer a useful warship and removed her from the 1902 budget estimates.[16] She was nevertheless retained in reserve in Saigon, French Indochina in 1903, along with Redoutable and three gunboats.[17] The ships remained in reserve in Saigon in 1904.[18] The ship was struck from the naval register in 1905, though her ultimate fate is unknown.[2]

Notes

- Ropp, p. 97.

- Gardiner, p. 303.

- Dale, p. 405.

- Brassey 1886, p. 29.

- Brassey 1888, pp. 208–213.

- Brassey 1890, pp. 33–36, 64.

- Brassey 1891, pp. 33–40.

- Thursfield, pp. 61–67.

- Brassey 1893, p. 70.

- Brassey 1895, p. 51.

- Weyl, p. 96.

- Brassey 1899, p. 73.

- Leyland 1900, p. 65.

- Leyland 1901, pp. 75–77.

- Marine Casualties, p. 170.

- Brassey & Leyland, p. 17.

- Brassey 1903, pp. 62–63.

- Brassey 1904, p. 90.

References

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1886). "Chapter IV: General Efficiency of the British Naval Administration". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 28–30. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1888). "French Naval Manoeuvres, 1886". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 207–224. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1890). "Chapter II: Foreign Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1891). "Foreign Maneouvres: I—France". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 33–40. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1893). "Chapter IV: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 66–73. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1895). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 49–59. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1899). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 70–80. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1903). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 57–68. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1904). "Chapter IV: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 86–107. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. & Leyland, John (1902). "Chapter II: Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 15–46. OCLC 496786828.

- Dale, George F. (1982). Wright, Christopher C. (ed.). "Question 23/81". Warship International. Toledo: International Naval Research Organization. XIX (4): 404–405. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Leyland, John (1900). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 63–70. OCLC 496786828.

- Leyland, John (1901). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter IV: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 71–79. OCLC 496786828.

- "Marine Casualties". Notes on Naval Progress. Washington, D.C.: United States Office of Naval Intelligence. 20: 161–181. July 1901. OCLC 699264868.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1892). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Foreign Naval Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 61–88. OCLC 496786828.

- Weyl, E. (1896). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter IV: The French Navy". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 61–72. OCLC 496786828.