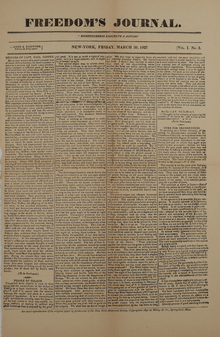

Freedom's Journal

Freedom's Journal was the first African-American owned and operated newspaper published in the United States.[1] Founded by Rev. John Wilk and other free black men in New York City, it was published weekly starting with the 16 March 1827 issue. Freedom's Journal was superseded in 1829 by The Rights of All, published between 1829 and 1830 by Samuel Cornish, the former senior editor of the Journal.

Volume 1, no.3, 23 March 1827 | |

| Type | Weekly newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Tabloid |

| Owner(s) | John Russwurm Samuel Cornish |

| Publisher | Cornish & Russwurm |

| Editor | John B. Russwurm Samuel Cornish |

| Founded | 16 March 1827 |

| Language | English |

| Ceased publication | 28 March 1829 |

| Headquarters | New York City |

| OCLC number | 1570144 |

Background

The newspaper was founded by Peter Williams, Jr. and other leading free blacks in New York City, including orator and abolitionist William Hamilton. The founders intended to appeal to free blacks throughout the United States, who were desperately attempting to elevate their literacy rate and finding some success at that. During this time, the free black American population in the U.S was about 300,000. The largest population of free black Americans after 1810 was in the slave state of Maryland, as slaves and free blacks lived in the same communities. [2] In New York State, a gradual emancipation law was passed in 1799, granting freedom to enslaved children born after July 4, 1799 after a period of indentured servitude into their 20s. In 1817 a new law was adopted, which quickened the emancipation process for virtually all who remained in slavery. The last slave was freed in 1827.

By this time, the United States and Great Britain had banned the African slave trade in 1808. But, slavery was expanding rapidly in the Deep South, because of the demand for labor to develop new cotton plantations there; a massive forced migration had been under way as a result of the domestic slave trade, as slaves were sold and taken overland or by sea from the Upper South to the new territories.

History

The newspaper founders selected Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwurm as senior and junior editors, respectively. Both men were community activists: Cornish was the first to establish an African-American Presbyterian church and Russwurm was a member of the Haytian Emigration Society. This group recruited and organized free blacks to emigrate to Haiti after its slaves achieved independence in 1804. It was the second republic in the Western Hemisphere and the first free republic governed by blacks.

According to the nineteenth-century African-American journalist, Irvine Garland Penn, Cornish and Russwurm's objective with Freedom's Journal was to oppose New York newspapers that attacked African Americans and encouraged slavery.[3] For example, Mordecai Noah wrote articles that degraded African Americans; other editors also wrote articles that mocked blacks and supported slavery.[4] The New York economy was strongly intertwined with the South and slavery; in 1822 half of its exports were cotton shipments. Its upstate textile mills processed southern cotton.[5]

The abolitionist press had focused its attention on opposing the paternalistic defense of slavery and the Southern culture's reliance on racist stereotypes. These typically portrayed slaves as children who needed the support of whites to survive or who were ignorant and happy as slaves. The stereotypes depicted blacks as inferior to whites and a threat to society if free.[6]

Cornish and Russwurm argued in their first issue: "Too long have others spoken for us, too long has the public been deceived by misrepresentations…." [7] They wanted the newspaper to strengthen the autonomy and common identity of African Americans in society.[8][9] "We deem it expedient to establish a paper," they remarked, "and bring into operation all the means with which out benevolent creator has endowed us, for the moral, religious, civil and literary improvement of our race…."[10]

Freedom's Journal provided international, national, and regional information on current events. Its editorials opposed slavery and other injustices. It also discussed current issues, such as the proposal by the American Colonization Society (ACS) to resettle free blacks in Liberia, a colony established for that purpose in West Africa.[1] Freedom's Journal printed two letters written by preeminent black American leaders of the time, both in opposition to the aims of the ACS. One man was the head of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.), Richard Allen, whose letter appeared in Nov. 1827 and the other was the Reverend Lewis Woodson, also associated with the A.M.E., whose letter appeared in Jan. 1829. Allen's letter was reprinted later, as part of David Walker's Appeal. [11]

The Journal published biographies of prominent blacks, and listings of the births, deaths, and marriages in the African-American community in New York, helping celebrate their achievements. It circulated in 11 states, the District of Columbia, Haiti, Europe, and Canada.[12]

The newspaper employed 14 to 44 subscription agents, such as David Walker, an abolitionist in Boston.[1]

Cornish left the paper and Russwurm began to promote colonization in Africa for American free blacks, as proposed by the American Colonization Society. His readers did not agree and abandoned the paper, which closed in 1829. It was superseded as The Rights of All, founded by Samuel Cornish, the first senior editor of the Journal. It published between 1829 and 1830.[1]

See also

- List of African American firsts

References

- "Freedom's Journal", article on website for Stanley Nelson, The Black Press: Soldiers without Swords (documentary), PBS, 1998, accessed 30 May 2012

- Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone, (Harvard University Press, 1998), 372.

- Bacon, Jacqueline. The First African-American Newspaper: Freedom's Journal, Lexington Books, 2007, pp. 43-45

- Bacon (2007), Freedom's Journal, pp. 38-39

- "King Cotton: Dramatic Growth of the Cotton Trade" Archived 2013-03-30 at the Wayback Machine, New York Divided: Slavery and the Civil War, 2007, New-York Historical Society, accessed 12 May 2012

- Rhodes, Jane. "The Visibility of Race and Media History," Critical Studies in Mass Communication. Routledge, 1993, p. 186.

- Rhodes (1993), "The Visibility of Race", p. 186

- Bacon (2007), Freedom's Journal, p. 43.

- Rhodes (1993), "The Visibility of Race," p. 186

- Bacon (2007), Freedom's Journal, p. 42

- Allen was not only head of the A.M.E., but historian Charles H. Wesley wrote in his 1935 biography of Allen, that Allen was the first of the organizers of the black American people. The highlight of the Allen letter reads, "This land which we have watered with our tears and our blood is now our mother country, and we are well satisfied to stay where wisdom abounds and the gospel is free." Historian Floyd Miller found Woodson to be the 'Father of Black Nationalism.' Woodson's letter took on a more defiant style, "Africa, is with us entirely out of the question, we never asked for it...we never wanted it; neither will we ever go to it." Floyd Miller, "The Father of Black Nationalism," Civil War History, vol. 17, no. 4, Dec. 1971.

- Freedom's Journal, Wisconsin History

Further reading

- Bacon, Jacqueline. "The history of Freedom's Journal: A study in empowerment and community." Journal of African American History 88.1 (2003): 1-20. in JSTOR

- Bacon, Jacqueline. Freedom's journal: the first African-American newspaper (Lexington Books, 2007).

- Bacon, Jacqueline. "“Acting as Freemen”: Rhetoric, Race, and Reform in the Debate over Colonization in Freedom's Journal, 1827–1828." Quarterly Journal of Speech 93.1 (2007): 58-83.

- Dann, Martin. The Black Press, 1827-1890: The Quest for National Identity. New York: G.P. Putnam Sons, 1971.

- Penn, I. Garland. The Afro-American Press and its Editors. Salem, New Hampshire: Ayer Company, Publishers, Inc., 1891.

- Vogel, Todd, ed. The Black Press: New Literary and Historical Essays, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

- Yingling, Charlton W., "No One Who Reads the History of Hayti Can Doubt the Capacity of Colored Men: Racial Formation and Atlantic Rehabilitation in New York City’s Early Black Press, 1827-1841," Early American Studies 11, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 314–348.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Freedom's Journal. |

- Freedom's Journal, Wisconsin History, includes digitized facsimiles of all 103 issues.

- Newspapers: Freedom's Journal, article on website for The Black Press: Soldiers without Swords (90-min. documentary by Stanley Nelson), PBS, 1998