Frederick J. Osterling

Frederick John Osterling (October 4, 1865, Duquesne, Pennsylvania – July 5, 1934, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) was an American architect, practicing in Pittsburgh from 1888.

Frederick J. Osterling was born to Philip and Bertha Osterling in Dravosburg, Pennsylvania, in 1865. The Osterling family moved to Allegheny City when Frederick was young. Following his schooling in Allegheny City, Osterling began work in the office of Joseph Stillburg, and was published in American Architect and Building News at age 18.[1] Following a period of European travel, he launched his own practice in 1888. During his career he designed many prominent Pittsburgh buildings, such as the Union Trust Building (1915–17). According to Martin Aurand, Architecture Librarian at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh,[2] Osterling's practice faltered after controversy relating to his anticipated alteration to the landmark H.H. Richardson Allegheny County Courthouse and a public lawsuit filed by the industrialist Henry Clay Frick. Osterling's studio was in a building he designed himself in 1917 at 228 Isabella Street in Pittsburgh's North Shore neighborhood.

Some of Osterling’s works are pictured in a book entitled ," F. J. Osterling Architect" , Murdoch-Kerr Press, Pittsburg, 1904. The book contains about 40 plates (some lithos, some artists drawings) depicting Osterling’s works. These plates include views of the Washington County, Pennsylvania Court House, its portico and law library; the entrance and smoking room of the Syria Temple (Pittsburgh); and the residences H.H. Westinghouse and other notable Western Pennsylvanians.

Significant buildings designed by Osterling in chronological order

All buildings are in Pittsburgh unless otherwise stated; italics denote a registered Historic Landmark:

- Charles Schwab House (541 Jones Avenue, North Braddock), 1889

- Heinz Company Factories, 1889

- Bellefield Presbyterian Church (Bellefield and 5th Ave) 1889; only the bell tower remains),[3]

- Westinghouse Air Brake Company General Office Building (Wilmerding, Pennsylvania), 1889–1890

- Bell Telephone of Pennsylvania Building, now Verizon Building (416-420 Seventh Avenue), 1890

- Marine Bank Building, later known as Fort Pitt Federal Building (301 Smithfield Street), 1890

- Times Building (334-336 Fourth Avenue), 1892

- Byrnes & Kiefer Building(1133 Penn Avenue), 1892

- Clayton, now the Frick Art & Historical Center, 1892 remodeling by Osterling of an 1870s house at 7200 Penn Avenue. This was the home of Henry Clay Frick, the industrialist.

- First Methodist Church, now Shadyside Seventh Day Adventist Church (821 South Aiken Avenue), 1893

- Chautauqua Lake Ice Company Warehouse, now the Heinz History Center (1212 Smallman Street), 1898

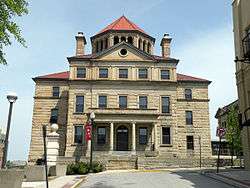

- Washington County Courthouse & Jail (Washington, Pennsylvania), 1899–1900

- Allegheny County Morgue (Originally on Forbes Avenue; the building was physically moved to 542 Fourth Avenue in 1929), built 1901

- Armstrong Cork Company Building, now The Cork Factory Lofts (2349 Railroad Street at 23rd Street), 1901

- Basilica of St. Michael the Archangel in Loretto, Pennsylvania, 1901[4]

- Hays Hall, a residence hall at Washington & Jefferson College in Washington, Pennsylvania,[5] built from 1901 to 1903 (demolished in 1994)

- Washington Trust Building, Washington, Pennsylvania, 1902[6]

- Arrott Building (401 Wood Street), 1902

- Colonial Trust Company Building, now part of the Bank Center of Point Park University (Wood Street, between Forbes and Fourth Avenues), 1902. Also, Osterling designed a T-shaped lobby that was added to his original building in 1926.

- Carnegie Free Library of Beaver Falls (Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania), 1903

- Iroquois Apartments, now offices (3600 Forbes Avenue), 1903

- Allegheny County Jail (Ross Street), 1903-1905 additions by Osterling to the 1886 building by Henry Hobson Richardson

- Allegheny High School, now Allegheny Middle School (810 Arch Street), 1904

- Commonwealth Trust Building (312 Fourth Avenue), 1907

- Luzerne County Courthouse (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), 1909

- Parkvale Building (200 Meyran Ave), 1911[7]

- Union Trust Building (501 Grant Street), 1917

- Gwinner-Harter House, also known as the William B. Negley House (5061 Fifth Avenue) was designed by an unknown architect and built 1870-1871. However, Osterling was responsible for additions between 1912 and 1923.

- Osterling Flats, date unavailable. These are three houses at 3603-3607 California Avenue with Dutch design elements, which were converted into condos by the Brighton Heights Citizens' Federation in 2003.[8]

Gallery

The 1889 bell tower from the former Bellefield Presbyterian Church is all that remains in front of the University of Pittsburgh's Bellefield Towers building

The 1889 bell tower from the former Bellefield Presbyterian Church is all that remains in front of the University of Pittsburgh's Bellefield Towers building Westinghouse Air Brake Company General Office Building in Wilmerding, PA. Built in 1889-1890.

Westinghouse Air Brake Company General Office Building in Wilmerding, PA. Built in 1889-1890. The Frick Mansion, or "Clayton", at 7200 Penn Avenue was built in the 1870s. Original architect: Unknown. Modifications by Andrew Peebles in 1883, and further remodeling done by Osterling in 1892.

The Frick Mansion, or "Clayton", at 7200 Penn Avenue was built in the 1870s. Original architect: Unknown. Modifications by Andrew Peebles in 1883, and further remodeling done by Osterling in 1892.- Chautauqua Lake Ice Company Warehouse (1898), now the Heinz History Center.

- Washington County Courthouse (1900)

Basilica of St. Michael the Archangel in Loretto, Pennsylvania (1901)

Basilica of St. Michael the Archangel in Loretto, Pennsylvania (1901) Hays Hall at Washington & Jefferson College, built from 1901 to 1903 (demolished in 1994).

Hays Hall at Washington & Jefferson College, built from 1901 to 1903 (demolished in 1994). Allegheny County Mortuary, built between 1901 and 1903, in Downtown Pittsburgh.

Allegheny County Mortuary, built between 1901 and 1903, in Downtown Pittsburgh. Arrott Building in Downtown Pittsburgh (1902).

Arrott Building in Downtown Pittsburgh (1902). Additions to Allegheny County Jail. H. H. Richardson's Ross Street jail was completed in 1886. Additions were added by Osterling from 1903 to 1905.

Additions to Allegheny County Jail. H. H. Richardson's Ross Street jail was completed in 1886. Additions were added by Osterling from 1903 to 1905. Allegheny High School (1904).

Allegheny High School (1904). Luzerne County Courthouse in Wilkes-Barre, PA (1909).

Luzerne County Courthouse in Wilkes-Barre, PA (1909). Negley-Gwinner-Harter House, built in 1870 and 1871, at 5061 Fifth Avenue. Original architect: Unknown, but Osterling remodeled the house and was responsible for additions between 1912 and 1923.

Negley-Gwinner-Harter House, built in 1870 and 1871, at 5061 Fifth Avenue. Original architect: Unknown, but Osterling remodeled the house and was responsible for additions between 1912 and 1923.

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frederick J. Osterling. |

- Frederick J. Osterling Photographs, ca. 1889-c1910, DAR.2014.01 Archived 2015-12-12 at the Wayback Machine, The Darlington Collection, Special Collections Department, University of Pittsburgh

- Aurand, Frederick J. Osterling and a Tale of Two Buildings, exhibition catalogue, Pennsylvania Heritage 15:2

- Kidney, Walter C. (2005). Oakland. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 0-7385-3867-1. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- Lu Donnelly; H. David Brumble IV; Franklin Toker (2010). Buildings of Pennsylvania: Pittsburg and Western Pennsylvania. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 304. ISBN 9780813928234.

- "Agreement submitted to the Board of Trustees by F.J. Osterling". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. January 2, 1901. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- "Washington Trust Building up for sale". Observer Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. 2010-04-26. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- Lubenau, Joel O. (Winter 2011). "Vanadium: Stained Gglass, Helpful Metal". Western Pennsylvania History. 94 (4): 52. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- Post-Gazette, May 3, 2003

External links

- Structures by Osterling

- "Osterling at phlf.org". Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

References

- J. Franklin Nelson, comp. Works of F. J. Osterling, Architect, Pittsburg. Pittsburgh: Murdoch-Kerr Press, 1904.

- Franklin Toker, Buildings of Pittsburgh, Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-8139-2650-6.

- Franklin Toker, Pittsburgh: An Urban Portrait, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-8229-5434-7..

- James D. Van Trump & Arthur P. Ziegler, Jr., Landmark Architecture of Allegheny County Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 1967, No ISBN.