Fort Amsterdam

Fort Amsterdam was a fort on the southern tip of Manhattan at the confluence of the Hudson and East rivers. It was the administrative headquarters for the Dutch and then English/British rule of the colony of New Netherland and subsequently the Province of New York from 1625 or 1626, until being torn down in 1790 after the American Revolution. It was the nucleus of the settlement in the area that became New Amsterdam and eventually New York City.

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

|

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

In its subsequent history it was known under various such names as Fort James, Fort Willem Hendrick and its anglicized Fort William Henry, Fort Anne, and Fort George. The fort changed hands eight times in various battles including the Battle of Long Island in the American Revolution, when volleys were exchanged between the fort and British emplacements on Governor's Island. After the fort's demolition Government House was constructed on the site as a possible house for the United States President. The site is now occupied by the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, which houses the National Museum of the American Indian; Bowling Green is nearby.

The construction of the fort marked the official founding date of New York City as recognized by the its seal. In October 1683 what would become the first session of the New York legislature convened at the fort. Guns at the fort formed a battery that would later be the namesake of nearby Battery Park.

History

Dutch rule (1625/1626–1664)

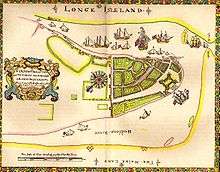

Fort Amsterdam was designed by Cryn Fredericks, chief engineer of the New Netherland colony. Seventeenth-century Dutch forts all followed a similar design. Probably originally intended as a standard star-shaped fort, Fort Amsterdam had four sides with a bastion at each corner to better protect the walls. The fort was built of hard-packed earth or rubble because earthworks would absorb cannon fire without collapsing as stone walls might. Much of the construction was probably done by enslaved Africans held by the Dutch West India Company.[1]

The fort was constructed at the southern tip of Manhattan Island, at the junction of the East and North (now known as the Hudson) rivers. Building commenced in 1625 under the direction of Willem Verhulst, the second director of the New Netherland colony. The elevation of the site was originally somewhat higher than it is today. The fort stood on a hill that sloped down to Pearl Street and Bowling Green.[2] (The hill was cut down in 1788, when the fort was demolished, and the site was graded to approximately its present level.)

At the time, Manhattan was sparsely settled, as most of the Dutch West India Company operations were upriver along the Hudson in order to conduct trading operation for beaver pelts.[3] According to John Romeyn Brodhead, while the fort was under construction, three Wechquaesgeek individuals traveled south from the area of present-day Westchester County to barter beaver skins. When they reached the Kolck, a pond near what is now Chinatown, they were set upon by three farmhands, and one of the two adults was killed. When the young boy who was with them grew older, he took his revenge for the murder of his uncle, which act served as a pretext for Kieft's War.[4]

The fort was the nucleus of the New Amsterdam settlement and its mission was protecting New Netherland colony operations in the Hudson River against attack from the English and the French. Although its main function was military, it also served as the center of trading activity. It contained a barracks, a church, a house for the West India Company director, and a warehouse for the storage of company goods.[5]

Troops from the fort used the triangle between the Heerestraat and what came to be known as Whitehall Street for marching drills.

It is sometimes asserted that around 1620, the Dutch East India Company contacted the English architect Inigo Jones asking him to design a fortification for the harbor. Jones responded in a letter with a plan for a star-shaped fortification made of stone and lime, surrounded by a moat, and defended with cannon. Jones advised the company against constructing a timber fort out of haste. The involvement of Jones cannot be corroborated with reliable documentary evidence.

English rule (1664–1673)

In autumn 1664, four English warships with several hundred soldiers onboard arrived in New Amsterdam’s harbor and demanded the Dutch surrender. Although Peter Stuyvesant at least outwardly prepared to fight, prominent city residents persuaded him to stand down, and on September 8 he signed the colony over without any blood being shed in one of the skirmishes of the larger Second Anglo–Dutch War. The English renamed the fort Fort James, in honour of James II of England, and New Amsterdam was renamed New York in recognition of James's title as Duke of York.[6]

Dutch rule (1673–1674)

In August 1673, the Dutch brought in a fleet of 21 ships and recaptured Manhattan. The Dutch attack was part of the bigger Third Anglo-Dutch War. The fort was renamed Fort Willem Hendrick in honor of William III of England, who was Stadtholder and Prince of Orange, and New York was renamed New Orange. In 1674, the fort and New Orange were turned back over to the English in the Treaty of Westminster (1674) which ended the war (the Dutch got Suriname).

English rule (1674–1689)

The English once again named the area "New York" and returned the Fort James name. In September 1682, James, Lord Proprietor of the Province of New York, appointed Thomas Dongan, 2nd Earl of Limerick as Vice-admiral in the Navy and provincial governor (1683–1688) to replace Edmund Andros[7] "Dongan's long service in the French army had made him conversant with the French character and diplomacy and his campaigns in the Low Countries had given him a knowledge of the Dutch language."[8]

At the time of his appointment, the province was bankrupt and in a state of rebellion. Dongan was able to restore order and stability. Dongan convened the first legislature of New York in October 1683 for a meeting at the fort. Dongan was also the first to establish batteries of cannon to the south of the fort.[9]

Colonist rule (1689–1691)

In 1689, following the Glorious Revolution (English Revolution of 1688), in which William and Mary acceded to the throne, German-born colonist Jacob Leisler seized the fort in what was called Leisler's Rebellion. He represented the common people against a group of wealthy leaders represented by Pieter Stuyvesant and others and enacted a government of direct popular representation. By some accounts, he also acted to redistribute wealth to the poor.

English/British rule (1691–1775)

Leisler's rule ended in 1691, when British sovereign William's new governor (appointed in 1690) finally reached New York. The fort had earlier been named for Willem when he was head of the Dutch government. He became the sovereign of the English government by the overthrow of James in the Glorious Revolution. The fort was renamed Fort William Henry in honor of the new Protestant king.[10]

The fort continued to be named for subsequent British sovereigns: Fort Anne (for Anne, Queen of Great Britain) and Fort George for the succession of Georgean monarchs (George I of Great Britain, George II of Great Britain, George III of the United Kingdom).

92 guns were added to the battery in 1756 during the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years' War.

Colonist/rebel rule (1775–1776)

The fort became the target of American rioting following Parliament's passage of the Stamp Act 1765. Activists spiked the guns at the battery to make them inoperable.

In the American Revolution, the colonists under George Washington seized the fort in 1775,[11] before the colonies formally seceded from the British Empire. During the Battle of Long Island, guns from the fort engaged British frigates starting on July 12, 1776. Between September 2 and 14, the fort and British guns on Governors Island exchanged volleys.

British rule (1776-1783)

The British recaptured the fort along with lower Manhattan in September 1776. They occupied the city and ruled New York from the fort throughout the war. Thousands of slaves migrated to the British lines in New York to gain promised freedom by fighting with them during the war. A large camp of freedmen was set up nearby.

Afterward, the British evacuated more than 3,000 former slaves from New York to Nova Scotia, to fulfill their promise. Others were taken to the Caribbean and some to London. Many found the climate harsh in Nova Scotia, and supplies late and limited. They struggled to settle there, also having to deal with slaveholding Loyalists. More than 1,700 former African Americans emigrated to Freetown, Sierra Leone in 1792, after Britain set up a new colony in West Africa for free blacks and liberated slaves.

American rule (1783–1790)

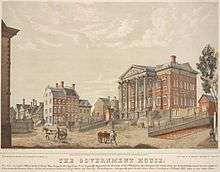

The Americans took over the fort in Manhattan on Evacuation Day, November 25, 1783, after the British pulled out. In 1788, the government ordered the razing of Fort George (as it was then known). Its materials were used as landfill to add to the shore and expand the Battery.[12] The fort was torn down in 1790, and the Government House, intended as the presidential residence, was built on the site.

The need for new fortifications soon became apparent, especially as tensions started rising again with France and Great Britain. In 1798, guns were placed in temporary fortifications on the Battery. Eventually a new fort, Castle Clinton, was built on Lower Manhattan to the southwest, shortly before the outbreak of the War of 1812 with Britain.[13]

The site of Fort James was redeveloped for the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House. Prior to landfilling and the creation of Battery Park, it was located at the shoreline of the Hudson River but is now a few blocks away.

See also

- Amsterdam (city), New York, a city in Upstate New York

- Bowling Green, the public park abutting the north side of the fort's site

References

- "History of Slavery in New York". Slavery in New York.

- Davis, Asahel (1854). History of New Amsterdam. New York: R. T. Young. p. 23.

history of fort amsterdam nyc.

- "Fort Amsterdam". New Netherland Institute.

- Brodhead, John Romeyn (1853). History of the State of New York. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 774.

history of fort amsterdam nyc.

- National Parks of New York Harbor Conservancy. The New Amsterdam Trail (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-04. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- Hemstreet, Charles (1905). Nooks and Corners of Old New York. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- The Memorial History of the City of New York, page 400 (appointment)and 453 (supersession)

- Phelan, Thomas P. "Thomas Dongan, Catholic Colonial Governor of New York". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, vol. 22, no. 4, 1911, pp. 207–237. JSTOR

- Driscoll, John T. "Thomas Dongan." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 6 Jun. 2014

- Carleton, Guy Lee; Thorpe, Francis Newton (1904). "The Dutch Under English Rule". The History of North America. New York: G. Barrie & sons. p. 167.

Willem Hendrick.

- "Fort George". dmna.ny.gov. February 19, 2006. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- "The Battery". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

- "Historic Timeline of The Battery". The Battery Conservancy. Archived from the original on 2009-02-28. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Amsterdam. |

- "Fort George". dmna.ny.gov.

- "George Washington's New York: Virtual tour". nyharborparks.org.

- "Map of Fort George 1773". memory.loc.gov. See Map # 1