Eguisheim

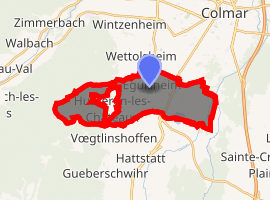

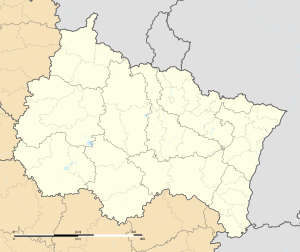

Eguisheim (German: Egisheim; Alsatian: Egsa) is a commune in the Haut-Rhin department in Grand Est in north-eastern France.

Eguisheim | |

|---|---|

Street in Eguisheim | |

Coat of arms | |

Location of Eguisheim

| |

Eguisheim  Eguisheim | |

| Coordinates: 48°02′37″N 7°18′24″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Grand Est |

| Department | Haut-Rhin |

| Arrondissement | Colmar-Ribeauvillé |

| Canton | Wintzenheim |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Claude Centlivre |

| Area 1 | 14.13 km2 (5.46 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-01-01)[1] | 1,726 |

| • Density | 120/km2 (320/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 68078 /68420 |

| Elevation | 191–764 m (627–2,507 ft) (avg. 210 m or 690 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Eguisheim produces Alsace wine of high quality. In May 2013 it was voted the «Village préféré des Français» (Favorite French Village), an annual distinction that passes from town to town throughout France.

History

Human presence in the area as early as the Paleolithic age is testified by archaeological excavations. Two parts from a human skull (from the frontal and parietal bones) were found in 1865 and given to Charles-Frédéric Faudel, a physician in nearby Colmar, who carefully described the find[2] and noted they were found undisturbed between animal bones, which allowed for a relative dating at a time when the very existence of prehistoric humans was still doubted.[3] The find became known in France in 1867 through Paul Broca,[4] and subsequently became a topic of discussion in the debate over what would become Paleoanthropology.[3] Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau and Ernest Hamy, in their 1873 Crania ethnica, grouped Eguisheim and others with the finds at Neanderthal and Naulette, creating a "race of Canstadt" that was so flexible that almost all fossil remains of humans would fit.[5]

Gustav Schwalbe (who first published on the skull in 1897[6]), in a comparison with other skull fragments including those found in Spy, Belgium, concluded the skull was sufficiently different from Neanderthal skulls and approached the measurements of modern humans. One reviewer cast some doubt on Schwalbe's comparison and argued that only the cranial vault was substantially different from the others, but this, he said, could have been a normal variation from the mean within a group.[7] Later scholars seem to have accepted the identification of the skull as belonging to a Neanderthal,[8] though Schwalbe again, in 1902, insisted on the difference between the Eguisheim and Neanderthal skulls.[9] In 1904 Schwalbe proposed a species he called Homo primigenius for what at least one of his contemporaries called Home neandertalensis, and excluded the Eguisheim skull from that category.[10]

In early historic times it was inhabited by the Gaul tribe of the Senones; the Romans conquered the village and developed here the cultivation of wine.

In the early Middle Ages, the Dukes of Alsace built here a castle (11th century) around which the current settlement developed. The commune was the alleged birthplace of Pope Leo IX in June 1002.

Tourism

The village centre receives many tourists, as the Alsace "Wine Route" passes the village. The village is also a member of the Les Plus Beaux Villages de France ("The most beautiful villages of France") association. (Its 2013 election is expected to increase visitation by up to 70%.)

Notable people

Leo IX, 1002 - 1054, pope of the Catholic Church from 12 February 1049 to his death in 1054.

International relations

Eguisheim is twinned with

.svg.png)

It has also friendship agreements with:

.svg.png)

See also

- Communes of the Haut-Rhin département

References

- "Populations légales 2017". INSEE. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Faudel, Charles-Frédéric (1866). "Sur la découverte d'ossements humains fossiles dans le lehm alpin de la vallée du Rhin à Eguisheim, prês de Colmar". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences. 63: 689–691.

- Goodrum, Matthew R. (2014). "Crafting a New Science: Defining Paleoanthropology and Its Relationship to Prehistoric Archaeology, 1860–1890". Isis. 105 (4): 706–33. doi:10.1086/679420. JSTOR 10.1086/679420.

- Broca, Paul (1867). "Fragments de crâne humaine d'Eguisheim". Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris. 2: 129–131. doi:10.3406/bmsap.1867.4286.

- Leroi-Gourhan, André (1993). "The Image of Ourselves". In White, Randall (ed.). Gesture and Speech. Translated by Berger, Anna Bostock. MIT Press. pp. 3–24. ISBN 9780262121736.

- Schwalbe, Gustav (1897). "Über die Schadelformen der altesten Menschenrassen, mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des Schadels von Egisheim". Mitteilungen der philomathischen Gesellschaft in Elsas-Lothringen. 5 (3).

- Zaborowski-Moindron, Sigismond (1899). "L'homo neanderthaliensis et le crâne d'Eguisheim". Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris. 10: 283–93. doi:10.3406/bmsap.1899.5841.

- Hewitt, J. F. (1897). "History as told in the cave deposits in the Ardennes: The travels of the cavemen of the Stone Age, and their legends". The Westminster Review. 147: 484–597.

- Duckworth, B. L. H. (1903). "Reviews: Craniology; Bluid, Schwalbe". Man: 77–78.

- MacCurdy, George Grant (1904). "Reviewed Work: Die Vorgeschichte des Menschen by G. Schwalbe". American Anthropologist. New Series. 6 (2): 336–38. doi:10.1525/aa.1904.6.2.02a00100. JSTOR 659078.

- INSEE

- ['Eguisheim «Village préféré des Français» en 2013' in "L'Alsace.fr" http://www.lalsace.fr/haut-rhin/2013/06/05/eguisheim-est-village-prefere-des-francais-en-2013]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eguisheim. |