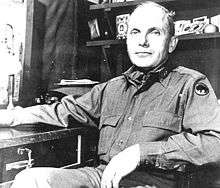

Edward Almond

Edward Mallory "Ned" Almond (December 12, 1892 – June 11, 1979) was a senior United States Army officer who fought in both World War I and World War II, where he commanded the 92nd Infantry Division. He is perhaps best known as the commander of the U.S. X Corps during the Korean War.

Edward Almond | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Edward Mallory Almond |

| Nickname(s) | "Ned" |

| Born | December 12, 1892 Luray, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | June 11, 1979 (aged 86) Anniston, Alabama, U.S. |

| Buried | Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, U.S. |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1916–1953 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | |

| Commands held | 92nd Infantry Division 2nd Infantry Division X Corps United States Army War College |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II Korean War |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross (2) Army Distinguished Service Medal (2) Silver Star (2) Purple Heart |

Early life and World War I

Born on December 12, 1892 in Luray, Virginia,[1] Almond graduated from the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in 1915 and joined the United States Army. He served in France during the latter stages of World War I. He fought in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive of late 1918, during which he was wounded and received the Silver Star. He ended the war as a commander of a machine-gun battalion.[2]

Interbellum

On returning to the United States after the war, Almond taught military science at Marion Military Institute from 1919 to 1924. He then attended Infantry School at Fort Benning in Georgia after which he resumed teaching at Marion until 1928.[1] He also taught at the Infantry School at Fort Benning, becoming acquainted with Lieutenant Colonel George Marshall, the assistant commandant of the school.[2]

In 1930, Almond graduated from the Command & General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. After a tour of duty in Philippines, where he commanded a battalion of Philippine Scouts,[2] he attended the Army War College in 1934 after which he was attached to the Intelligence Division of the General Staff for four years. Having been promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1938,[1] he attended the Army War College, Air Corps Tactical School,[2] and finally the Naval War College, from which he graduated in 1940. Almond was then assigned to staff duty at VI Corps HQ, Providence, Rhode Island.[1]

World War II

_Division_in_Italy%2C_inspects_his_troops_during_a_decoration_ceremony.jpg)

Soon after the outbreak of World War II, Almond was promoted to brigadier general and named assistant commander of the 93rd Infantry Division, based in Arizona at the time.[3]

Almond was for a time highly regarded by George Marshall, also a VMI graduate, who was Army Chief of Staff during World War II. This regard accounted in part for Almond's promotion to major general ahead of most of his peers and subsequent command of the 92nd Infantry Division, made of almost exclusively African-American soldiers, a position he held from its formation in October 1942 until August 1945. He led the division in combat in the Italian campaign of 1944–1945.[4]

Although George Marshall picked Almond for this assignment because Marshall believed Almond would excel at this difficult assignment, the division performed poorly in combat with Almond blaming the division's poor performance on its largely African-American troops, echoing the widespread prejudice in the segregated Army that blacks made poor soldiers[5]—and went on to advise the Army against ever again using African-Americans as combat troops. Almond told confidants that the division's poor combat record had cheated him of higher command.[6]

No white man wants to be accused of leaving the battle line. The Negro doesn't care.... people think being from the South we don't like Negroes.(sic.) Not at all, but we understand his capabilities. And we don't want to sit at the table with them.

— Edward Almond[7]

Occupation duty in Japan

In 1946 Almond was transferred to Tokyo as chief of personnel at General Douglas Macarthur's headquarters, normally a dead-end job. Almond very effectively handled the sizable challenge of staffing the occupation forces in Japan as American forces rapidly demobilized, standing out among MacArthur's lackluster staff. Having won MacArthur's confidence as capable and loyal,[8] Almond was the logical choice to become Chief of Staff in January 1949, when the incumbent, Paul Mueller, rotated home.[5]

Korean War and X Corps

After the initial North Korean attack in June 1950, United Nations forces were forced to withdraw and eventually fell back to the Pusan Perimeter.

MacArthur decided to counterattack with an amphibious invasion at Inchon in November. The invasion force, consisting of the 1st Marine Division and the 7th Infantry Division (United States), was originally named "X Force" and was placed under the command of General Almond. Because the name X Force was confusing to logistics officers, upon Almond's suggestion, the formation was re-designated as X Corps. MacArthur split X Corps from the 8th Army, then placed Almond, who had no experience with amphibious operations, in command of the main landing force just before the landings.

Almond earned the scorn of Marine officers when, during the early phase of the Inchon landing, he asked if the amphibious tractors used to land the Marines could float.[9] The invasion succeeded, but Almond did not pursue effectively and most of the routed North Korean Army escaped northwards.

During this time, Major General O. P. Smith,[9] commander of the 1st Marine Division, which was part of X Corps (and therefore under Almond's overall command) from October until December 1950 had many conflicts with Almond.

Almond also had a poor relationship with Lieutenant General Walton Harris Walker, commander of the 8th Army.

Historians have criticized Almond for the wide dispersal of his units during the X Corps advance into north-eastern part of North Korea, in November–December 1950. This dispersal contributed to the defeat of X Corps by Chinese troops, including the destruction of Task Force Faith, and the narrow escape of the Marines at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir.[6] Almond was slow to recognize the scale of the Chinese attack on X Corps, urging Army and Marine units forward despite the huge Chinese forces arrayed against them. Displaying his usual reckless boldness, he underestimated the strength and skill of the Chinese forces, at one point telling his subordinate officers "The enemy who is delaying you for the moment is nothing more than remnants of Chinese divisions fleeing north. We're still attacking and we're going all the way to the Yalu. Don't let a bunch of Chinese laundrymen stop you." As stated by a close associate: "When it paid to be aggressive, Ned was aggressive. When it paid to be cautious, Ned was aggressive."[5]

Despite these mistakes and partly due to his close relationship with General MacArthur, the new Eighth Army commander Lieutenant General Matthew Ridgway, who became the commander of the 8th Army following the death of General Walker in December 1950, retained Almond as commander of X Corps. Ridgway admired Almond's aggressive attitude, but felt he needed close supervision to ensure his boldness did not jeopardize his command. Almond and X Corps later took part in the defeat of the Chinese offensives during February and March 1951, as well as the Eighth Army's counter-offensive, Operation Killer.[5] Almond was promoted to lieutenant general in February 1951.

Future general and secretary of state Alexander Haig served as aide-de-camp to General Almond in the Korean War.

Post Korea

In July 1951, Almond was reassigned and became president of the U.S. Army War College.[10]

He retired from the Army on 31 January 1953 and worked as an insurance executive until his death in 1979.

Lieutenant General Almond is interred in Arlington National Cemetery near his son, Edward Mallory Almond Jr., a captain in the 157th Infantry Regiment, killed in action 19 March 1945 in France.[3][11]

Decorations

In popular culture

- In the novel series The Corps, General Almond is mentioned in the last two books: Under Fire and Retreat Hell! Almond is portrayed by the author (who served under Almond in the Korean War) in a positive light, with no reference made to his racial views.

- In James McBride's 2002 novel Miracle at St. Anna, the commanding general of the 92nd Infantry Division, General Allman, is based on Almond.

- In the 2008 Spike Lee film Miracle at St. Anna, Almond is portrayed by Robert John Burke.

References

- Wintermute 2013.

- Taaffe 2016, p. 67.

- "Edward Mallory Almond Lieutenant General, United States Army". Arlington National Cemetery website. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

Notes that his son (Edward Mallory Almond, Jr.) is buried with him at Arlington National Cemetery.

- Taaffe 2016, pp. 67–68.

- Blair, Clay (1987). The Forgotten War. New York: Times Books. pp. 32, 572.

- Halberstam 2007, pp. 161-162.

- Atkinson, Rick (2 October 2007). The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944 (The Liberation Trilogy Book 2). 7635: Henry Holt and Co.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Fehrenbach 1998, pp. 163.

- Coram, Robert (2010). Brute: The Life of Victor Krulak, U.S. Marine (illustrated ed.). Little, Brown and Company. pp. 207, 213. ISBN 978-0-316-75846-8. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- "Carlisle Barracks History". U.S. Army. Retrieved 2011-01-06.

- EM Almond Jr. at findagrave.com

Bibliography

- Blair, Clay (1987). The Forgotten War: America in Korea: 1950-1953. New York: Times Books. ISBN 0-8129-1670-0.

- Fehrenbach, T.R. (1998) [1963]. This Kind of War. Dulles, Virginia: Brassey's. ISBN 1-57488-259-7.

- Halberstam, David (2007). The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4013-0052-4.

- Russ, Martin (1999). Breakout: The Chosin Reservoir Campaign, Korea, 1950. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-029259-4.

- Taaffe, Stephen R. (2016). MacArthur's Korean War Generals. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2221-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wintermute, Bobby A. (2013). "Almond, Edward M.". In Bielakowski, Alexander M. (ed.). Ethnic and Racial Minorities in the U.S. Military [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598844276.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Almond. |

- Arlington National Cemetery listing

- Edward Almond at Find a Grave

- Wilson, Dale E. (1992). "Recipe for Failure: Major General Edward M. Almond and Preparation of the U.S. 92d Infantry Division for Combat in World War II, The Journal of Military History, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Jul 1992)". The Journal of Military History. 56 (3): 473–488. doi:10.2307/1985973. JSTOR 1985973.

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Newly activated post |

Commanding General 92nd Infantry Division 1942–1945 |

Succeeded by Post deactivated |

| Preceded by William Kelly Harrison, Jr. |

Commanding General 2nd Infantry Division 1945–1946 |

Succeeded by Post deactivated |

| Preceded by Newly activated post |

Commanding General X Corps 1950–1951 |

Succeeded by Clovis E. Byers |