E. Nesbit

Edith Nesbit (married name Edith Bland; 15 August 1858 – 4 May 1924) was an English author and poet; she published her books for children under the name of E. Nesbit.

Edith Nesbit | |

|---|---|

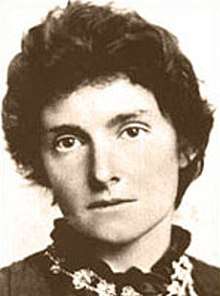

Edith Nesbit, ca. 1890 | |

| Born | 15 August 1858 Kennington, Surrey (now Greater London), England[1] |

| Died | 4 May 1924 (aged 65) New Romney, Kent, England |

| Pen name | E. Nesbit |

| Occupation | Writer, poet |

| Nationality | English |

| Period | 1886–1924 |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse | Thomas Tucker (m. 1917)

|

She wrote or collaborated on more than 60 books of children's literature. She was also a political activist and co-founded the Fabian Society, a socialist organisation later affiliated to the Labour Party.

Biography

Nesbit was born in 1858 at 38 Lower Kennington Lane in Kennington, Surrey (now classified as Inner London), the daughter of an agricultural chemist, John Collis Nesbit, who died in March 1862, before her fourth birthday.[2] Her sister Mary's ill health meant that the family travelled around for some years, living variously in Brighton, Buckinghamshire, France (Dieppe, Rouen, Paris, Tours, Poitiers, Angoulême, Bordeaux, Arcachon, Pau, Bagnères-de-Bigorre, and Dinan in Brittany), Spain and Germany, before settling for three years at Halstead Hall in Halstead in north-west Kent, a location which later inspired The Railway Children (this distinction has also been claimed by the Derbyshire town of New Mills).[3]

When Nesbit was seventeen, the family moved back to London, living in South East London in Elswick Road in Lewisham. There is still a plaque on the house to mark her time there.

At eighteen, Nesbit met the bank clerk Hubert Bland, who was her elder by three years, in 1877. Seven months pregnant, she married Bland on 22 April 1880, though she did not immediately live with him, as Bland initially continued to live with his mother. Their marriage was a tumultuous one. Early on Nesbit discovered that another woman believed she was Hubert's fiancée and had also borne him a child. A more serious blow came in 1886 when she discovered that her good friend, Alice Hoatson, was pregnant with Hubert's child. She had previously agreed to adopt Hoatson's child and allow Hoatson to live with her as their housekeeper. After she discovered the truth, they quarrelled violently and she suggested that Hoatson and the baby, Rosamund, should leave; her husband threatened to leave Edith if she disowned the baby and its mother. Hoatson remained with them as a housekeeper and secretary and became pregnant by Bland again 13 years later. Edith again adopted Hoatson's child, John.[4]

Nesbit's children by Bland were Paul Cyril Bland (1880–1940), to whom The Railway Children was dedicated; Mary Iris Bland (1881–1965), who married John Austin D Phillips in 1907;[5] and Fabian Bland (1885–1900). She also adopted Bland's two children by Alice Hoatson, Rosamund Edith Nesbit Hamilton, later Bland (1886–1950), who married Clifford Dyer Sharp on 16 October 1909,[6] and to whom The Book of Dragons was dedicated; and John Oliver Wentworth Bland (1899–1946)[7] to whom The House of Arden and Five Children and It were dedicated.[8] Nesbit's son Fabian died aged 15 after a tonsil operation; Nesbit dedicated several books to him such as The Story of the Treasure Seekers and its sequels as well as many others. Nesbit's adopted daughter Rosamund collaborated with her on the book Cat Tales.

Nesbit was a follower of the Marxist[9][10] socialist William Morris and she and her husband Hubert Bland were among the founders of the Fabian Society in 1884.[11] Their son Fabian was named after the society.[2] They also jointly edited the Society's journal Today; Hoatson was the Society's assistant secretary. Nesbit and Bland also dallied briefly with the Social Democratic Federation, but rejected it as too radical. Nesbit was an active lecturer and prolific writer on socialism during the 1880s. Nesbit also wrote with her husband under the name "Fabian Bland",[12] though this activity dwindled as her success as a children's author grew.

Nesbit lived from 1899 to 1920 in Well Hall, Eltham,[13] in southeast London, which appears in fictional guise in several of her books, especially The Red House. From 1911 she also maintained a second home on the Sussex Downs, in the hamlet of Crowlink, Friston, East Sussex. [14] She and her husband entertained a large circle of friends, colleagues and admirers at their Well Hall house.[15] On 20 February 1917, some three years after Bland died, Nesbit married Thomas "the Skipper" Tucker. They were married in Woolwich, where he was the captain of the Woolwich Ferry.

She was a guest speaker at the London School of Economics, which had been founded by other Fabian Society members.

Towards the end of her life, she moved to "Crowlink" in Friston, and later to "The Long Boat" at Jesson, St Mary's Bay, New Romney, East Kent where, probably suffering from lung cancer (she "smoked incessantly"),[16] she died in 1924 and was buried in the churchyard of St Mary in the Marsh. Her husband Thomas died at the same address on 17 May 1935. Edith's son Paul Bland was one of the executors of Thomas Tucker's will.

Writer

Nesbit published approximately 40 books for children, including novels, collections of stories and picture books.[17] Collaborating with others, she published almost as many more.

According to her biographer, Julia Briggs, Nesbit was "the first modern writer for children": Nesbit "helped to reverse the great tradition of children's literature inaugurated by Lewis Carroll, George MacDonald and Kenneth Grahame, in turning away from their secondary worlds to the tough truths to be won from encounters with things-as-they-are, previously the province of adult novels." Briggs also credits Nesbit with having invented the children's adventure story. Noël Coward was a great admirer of hers and, in a letter to an early biographer Noel Streatfeild, wrote: "she had an economy of phrase and an unparalleled talent for evoking hot summer days in the English countryside."[18]

Among Nesbit's best-known books are The Story of the Treasure Seekers (1899) and The Wouldbegoods (1901), which both recount stories about the Bastables, a middle-class family that has fallen on (relatively) hard times. The Railway Children is also known from its adaptation into a 1970 film version. Gore Vidal called the time-travel book, The Story of the Amulet, one in which "Nesbit's powers of invention are at their best."[19] Her children's writing also included numerous plays and collections of verse.

She created an innovative body of work that combined realistic, contemporary children in real-world settings with magical objects – what would now be classed as contemporary fantasy – and adventures and sometimes travel to fantastic worlds.[20] In doing so, she was a direct or indirect influence on many subsequent writers, including P. L. Travers (author of Mary Poppins), Edward Eager, Diana Wynne Jones and J. K. Rowling. C. S. Lewis was influenced by her in writing the Narnia[21] series and mentions the Bastable children in The Magician's Nephew. Michael Moorcock would go on to write a series of steampunk novels with an adult Oswald Bastable (of The Treasure Seekers) as the lead character. In 2012, Jacqueline Wilson wrote a sequel to the Psammead trilogy, titled Four Children and It.

Nesbit also wrote for adults, including eleven novels, short stories and four collections of horror stories.

Allegations of plagiarism

In 2011, Nesbit was accused of lifting the plot of The Railway Children from The House by the Railway by Ada J. Graves, a book first published in 1896 and serialised in a popular magazine in 1904, a year before The Railway Children first appeared.[22] In both works the children's adventures bear similarities. In the story, Nesbit's characters use red petticoats to stop the train whilst Graves has them using a red jacket.

Legacy

- Edith Nesbit Walk, also a cycle way, runs along the south side of Well Hall Pleasaunce in Eltham.[23]

- Also in south east London, at Lee Green, is Edith Nesbit Gardens.[24]

- A 200-metre walking path in Grove Park (connecting Baring Road to Reigate Road), south-east London is named Railway Children Walk to commemorate Nesbit's novel of the same name.[25] A similar path is located in Oxenhope[26] (a location on the Keighley and Worth Valley Railway used in filming the 1970 film).

A one-act, one-woman play titled Larks and Magic, based on Nesbit's life, was created by Alison Neil.[27][28][29]

Works

Novels for children

Bastable series

- 1899 The Story of the Treasure Seekers

- 1901 The Wouldbegoods

- 1904 The New Treasure Seekers

The Complete History of the Bastable Family (1928) is a posthumous omnibus of the three Bastable novels, but it is not the complete history. Four more stories about the Bastables are included in the 1905 collection Oswald Bastable and Others.[1] The Bastables also appear in the 1902 adult novel The Red House.

Psammead series

House of Arden series

- 1908 The House of Arden

- 1909 Harding's Luck

Other children's novels

- 1906 The Railway Children

- 1907 The Enchanted Castle

- 1910 The Magic City

- 1911 The Wonderful Garden

- 1913 Wet Magic

- 1925 Five of Us—and Madeline (published posthumously in the collection of the same name, below)[30]

Novels for adults

- 1885 The Prophet's Mantle (as Fabian Bland)[31]

- 1886 Something Wrong (as Fabian Bland)[31]

- 1896 The Marden Mystery (as Fabian Bland)[32] (Very rare; few if any copies have survived)[33]

- 1899 The Secret of Kyriels (Very rare; few if any copies have survived)[33]

- 1902 The Red House

- 1906 The Incomplete Amorist

- 1909 Salome and the Head (also published as The House with No Address)[1]

- 1909 Daphne in Fitzroy Street

- 1911 Dormant (US title, Rose Royal)

- 1916 The Incredible Honeymoon

- 1922 The Lark

Stories and story collections for children

- 1891 "The Pilot", poem, picture book(?), OCLC 905335060

- 1894 Miss Mischief

- 1895 Tick Tock, Tales of the Clock

- 1895 Pussy Tales

- 1895 Doggy Tales

- 1897 The Children's Shakespeare

- 1897 Royal Children of English History

- 1897 Tales Told in the Twilight (bed-time stories by multiple writers)

- 1898 The Book of Dogs

- 1899 Pussy and Doggy Tales

- 1901 The Book of Dragons (stories previously published in The Strand, 1899) †

- 1901 Nine Unlikely Tales

- 1902 The Revolt of the Toys

- 1903 The Rainbow Queen and Other Stories

- 1903 Playtime Stories

- 1904 The Story of Five Rebellious Dolls

- 1904 Cat Tales (by Nesbit and her daughter Rosamund E. Nesbit Bland)[34]

- 1905 Oswald Bastable and Others (includes four Bastable stories)[1]

- 1905 Pug Peter, King of Mouseland

- 1907 Beautiful Stories from Shakespeare (reprint of The Children's Shakespeare, 1895)

- 1908 The Old Nursery Stories

- 1912 The Magic World

- 1925 Five of Us—and Madeline (published posthumously, assembled and edited by Rosamund E. Nesbit Bland, comprising the title novel and two short stories perhaps completed by Nesbit)[30]

† The Book of Dragons (1901) comprised The Seven Dragons, a 7-part serial, and an eighth story, all published 1899 in The Strand Magazine. Augmented by a ninth story, "The Last of the Dragons" (posthumous, 1925), it was issued in 1972 as The Complete Book Of Dragons and in 1975 as The Last Of The Dragons and Some Others. The original title has been used since then, with the original contents augmented variously by "The Last of the Dragons" and material contemporary to the reissue. The title Seven Dragons and Other Stories has also been used for a latter-day Nesbit collection.[35]

Stories and story collections for adults

- 1893 Grim Tales (horror stories)

- 1893 Something Wrong (horror stories)

- 1893 "Hurst of Hurstcote"

- 1894 The Butler in Bohemia (by Nesbit and Oswald Barron), OCLC 72479308

- 1896 In Homespun (10 stories "written in an English dialect" of South Kent and Sussex)

- 1901 Thirteen Ways Home

- 1903 The Literary Sense

- 1906 Man and Maid (10 stories) (some supernatural stories) †

- 1908 "The Third Drug", Strand Magazine, February 1908 (reprinted in anthologies under that title and as "The Three Drugs")[36]

- 1909 These Little Ones

- 1910 Fear (horror stories)

- 1923 To the Adventurous

† According to John Clute, "Most of Nesbit's supernatural fiction" is short stories "assembled in four collections"; namely, Man and Maid and the three noted here as containing horror stories.[37]

Non-fiction

Poetry

- "The Time of Roses", undated (Victorian era 1890?)

- 1886 "Lays and Legends"

- 1887 "The Lily and the Cross"

- 1887 "The Star of Bethlehem"

- 1888 "The Better Part, and Other Poems"

- 1888 "Landscape and Song"

- 1888 "The Message of the Dove"

- 1888 "All Round the Year"

- 1888 "Leaves of Life"

- 1889 "Corals and Sea Songs"

- 1890 "Songs of Two Seasons"

- 1892 "Sweet Lavender"

- 1892 "Lays and Legends: Second Edition"

- 1895 "Rose Leaves"

- 1895 "A Pomander of Verse"

- 1898 "Songs of Love and Empire"

- 1901 "To Wish You Every Joy"

- 1905 "The Rainbow and the Rose"

- 1908 "Jesus in London"

- 1883–1908 "Ballads and Lyrics of Socialism"

- 1911 "Ballads and Verses of the Spiritual Life"

- 1912 "Garden Poems"

- 1922 "Many Voices"

References

- E. Nesbit at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDB). Retrieved 29 December 2013. Select a title to see its linked publication history and general information. Select a particular edition (title) for more data at that level, such as a front cover image or linked contents.

- Holmes, John R. (2007). "Guide to Literary Masters and Their Works – E. Nesbit". www.ebscohost.com. Literary Reference Center, EBSCOhost. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- "Railway Children battle lines are drawn". Telegraph & Argus. Bradford. 22 April 2000. Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- Langley Moore, Doris (1966). E. Nesbit: a biography. Philadelphia and New York: Chilton Books. pp. 70–71, 102–03.

- "Ancestry – Sign In". www.ancestry.co.uk.

- "Ancestry – Sign In". www.ancestry.co.uk.

- Bedson, S. P. (1947). "John Oliver Wentworth Bland (Born 6th October 1899. Died 10th May 1946)". The Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology. 59 (4): 716–721. doi:10.1002/path.1700590427.

- Lawrence, Ben (4 July 2016). "Five children and a philandering husband: E Nesbit's private life" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- Bennett, Phillippa, and Rosemary Miles (2010). William Morris in the Twenty-First Century. Peter Lang. ISBN 3034301065. p. 136.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Introduction". Five Children and It. London: Penguin Books Ltd. 1996. ISBN 9780140367355.

- The Prophet's Mantle (1885), a fictional story inspired by the life of Peter Kropotkin in London.

- "Well Hall" entry of London Gazetteer by Russ Willey, (Chambers 2006) ISBN 0-550-10326-0 (online extract )

- "Edith Nesbit". Women of Eastbourne.

- Iannello, Silvia (18 August 2008). "Edith Nesbit, la precorritrice della Rowling". Tvcinemateatro―i protagonisti. Silvia-iannello.blogspot.com (reprint 19 September 2011 from Zam (zam.it)). Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Gardner, Lyn (26 March 2005). "how did E Nesbit come to write such an idealised celebration of Victorian family life?". The Guardian.

- Lisle, Nicola (15 August 2008). "E Nesbit: Queen of Children's Literature". AbeBooks (abebooks.co.uk).

- Day, Barry (2009). The Letters of Noël Coward. New York: Vintage Books. March 2009. p. 74.

- Vidal, Gore (3 December 1964). "The Writing of E. Nesbit". The New York Review of Books. 3 (2). Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- Morrow, Clark Elder (October 2011). "Edith Nesbit: An Appreciation". Vocabula Review. 13 (10): 1–8. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- Nicholson, Mervyn (Fall 1998). "C. S. Lewis and the Scholarship of Imagination in E. Nesbit and Rider Haggard". Renascence. 51 (1): 41–62. doi:10.5840/renascence19985114. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- Copping, Jasper (20 March 2011). "The Railway Children 'plagiarised' from earlier story". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- "TQ4274 : Edith Nesbit Walk, Eltham". Geograph. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- "Edith Nesbit Gardens". Lewisham Parks and Open Spaces. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- "Railway Children Walk". www.geoview.info. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Jones, Roger. "Visit to Hebden Bridge". www.wordpress.com. Wordpress. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Larks and Magic at alisonneil.co.uk, Accessed 18 February 2018

- 'Larks and Magic', a new play by Alison Neil at uktw.co.uk, Accessed 18 February 2018

- BROCKWEIR EVENTS at the Mac Hall LARKS AND MAGIC Saturday 17th February, 7.30 for 8.00 Written and performed by Alison Neil at brockweirvillagehall.co.uk, Accessed 18 February 2018

- "Five of Us—and Madeline". ISFDB. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- Simkin, John. "Edith Nesbit". www.spartacus-educational.com. Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "Edith Nesbit Books". The Folio Society. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "E.Nesbit". Delphi Classics. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- OCLC 62770293

- "The Book of Dragons". ISFDB.

"The Seven Dragons and Other Stories". ISFDB. Retrieved 24 February 2015. - "The Third Drug". ISFDB. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- "Nesbit, E". SFE: The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (sf-encyclopedia.com). Entry by "JC", John Clute. Last updated 8 August 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "book lookup – Long ago when I was young". www.nla.gov.au. National Library of Australia. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Lovegrove, Chris. "The sweet white flowers of memory". www.wordpress.com. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Slave song. OCLC. OCLC 60194453.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Edith Nesbit |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edith Nesbit. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: E. Nesbit |

- E. Nesbit at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- "The Writing of E. Nesbit" by Gore Vidal, The New York Review of Books, 3 December 1964

- "Lost Lives: Edith Bland" by Bill Greenwell

- Nesbit at YourDictionary.com (reprint from Encyclopedia of World Biography)

- E. Nesbit at Library of Congress Authorities, with 140 catalogue records

- Rosamund E. Nesbit Bland at LC Authorities, with 2 records, and at WorldCat

- Eager, Edward (1 October 1958). "Daily Magic". The Horn Book Magazine. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Online texts

- Works by Edith Nesbit at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Edith (née Bland) Nesbit at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about E. Nesbit at Internet Archive

- Works by E. Nesbit at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Melisande by E. Nesbit, a tale similar to Rapunzel

- My School Days (article series by Nesbit)

- The Magic World