Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange (May 26, 1895 – October 11, 1965) was an American documentary photographer and photojournalist, best known for her Depression-era work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Lange's photographs influenced the development of documentary photography and humanized the consequences of the Great Depression.[1]

Dorothea Lange | |

|---|---|

Lange in 1936 | |

| Born | Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn May 26, 1895 Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | October 11, 1965 (aged 70) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Documentary photography, photojournalism |

| Spouse(s) | |

Early life

Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn was born on May 26, 1895, at 1041 Bloomfield Street, Hoboken, New Jersey[2][3] to second-generation German immigrants Heinrich Nutzhorn and Johanna Lange.[4] She "grew up on Manhattan’s Lower East Side ... and attended PS 62 on Hester Street, where she was one of the only gentiles — quite possibly the only — in a class of 3000 Jews."[5]

She had a younger brother, Martin.[4] She dropped her middle name and assumed her mother's maiden name after her father abandoned the family when she was twelve years old, one of two traumatic events early in her life.[6] The other trauma was her contraction of polio at age seven, which left her with a weakened right leg and a permanent limp.[2][3] "It formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me, and humiliated me," Lange once said of her altered gait. "I've never gotten over it, and I am aware of the force and power of it."[7]

Career

Lange graduated from the Wadleigh High School for Girls,[8] and although she had never operated or owned a camera, she was adamant that she would become a photographer upon graduating from high school.[9] Lange was educated in photography at Columbia University in New York City in a class taught by Clarence H. White.[9] She was informally apprenticed to several New York photography studios, including that of the famed Arnold Genthe.[6] In 1918, she left New York with a female friend to travel the world, but was forced to end the trip in San Francisco due to a robbery, and settled there, working as a photograph finisher at a photographic supply shop,[10] where she became acquainted with other photographers and met an investor who aided in the establishment of a successful portrait studio.[3][6][11] This business supported Lange and her family for the next fifteen years.[6] In 1920, she married the noted western painter Maynard Dixon, with whom she had two sons, Daniel, born in 1925, and John, born in 1930.[12]

Lange's early studio work mostly involved shooting portrait photographs of the social elite in San Francisco.[13] At the onset of the Great Depression, Lange turned her lens from the studio to the street. Her photographs during this period bear kinship with John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath.[14]

In 1933, at the height of the Depression, about fourteen million people were out of work. Many of them drifted aimlessly, with no place to live, many times without food. In addition, the dust storms of the Midwest created economic havoc. About 300,000 men, women and children came to California in the 1930s, hoping to find work. These migrant families were routinely called "Okies" regardless of where they were from. They traveled in beat-up cars, wandering from place to place, following the crops. Lange began to photograph these people from her studio window. Later, she left the studio so she could photograph them in the streets of California. Lange felt she had, at last, found her purpose and direction in photography. She roamed the streets with her camera, portraying the extent of the social and economic upheaval of the Depression. She was no longer a portraitist. Neither was she a photojournalist. She became known as a "documentary" photographer.[15]

Her studies of unemployed and homeless people, starting with White Angel Breadline (1933), which depicted a lone man facing away from the crowd in front of a soup kitchen run by a widow known as the White Angel,[16] captured the attention of local photographers and led to her employment with the federal Resettlement Administration (RA), later called the Farm Security Administration (FSA).

Lange learned to talk to her subjects when photographing them, which helped her to accompany her photographs with pertinent remarks. The titles of her works often were very personal and revealed a lot about her subjects.[15]

Resettlement Administration

In December 1935, Lange and Dixon divorced, and she married economist Paul Schuster Taylor, Professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley.[12] Traveling around the California coast as well as the Midwest,[5] for the next five years they documented rural poverty and the exploitation of sharecroppers and migrant laborers. Taylor interviewed subjects and gathered economic data, while Lange took photographs. Lange resided in Berkeley for the rest of her life.

Working for the Resettlement Administration and Farm Security Administration, Lange's images brought the plight of the poor and forgotten—particularly sharecroppers, displaced farm families, and migrant workers—to public attention. Distributed free to newspapers across the country, Lange's poignant images became icons of the era.

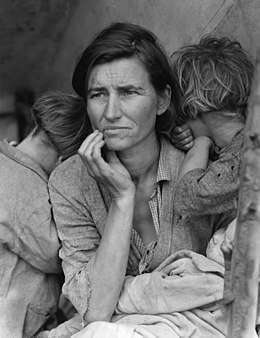

One of Lange's most recognized works is Migrant Mother.[17] The woman in the photograph is Florence Owens Thompson. In 1960, Lange spoke about her experience taking the photograph:

I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.[18]

After Lange returned home, she told the editor of a San Francisco newspaper about conditions at the camp and provided him with two of her photographs. The editor informed federal authorities and published an article that included the images. In response, the government rushed aid to the camp to prevent starvation.[19]

According to Thompson's son, Lange got some details of this story wrong, but the impact of the picture was based on the image of the strength and need of migrant workers.[20] Twenty-two of the photographs she took as part of the FSA were included in John Steinbeck's The Harvest Gypsies when it was originally published in The San Francisco News in 1936. According to an essay by photographer Martha Rosler, the photo became the most reproduced photograph in the world.[21]

Japanese American internment

In 1941, Lange was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for achievement in photography.[22] After the attack on Pearl Harbor, she gave up the prestigious fellowship to record the forced evacuation of Japanese Americans from the West Coast on assignment for the War Relocation Authority (WRA).[23] She covered the internment of Japanese Americans[24] and their subsequent incarceration, traveling throughout urban and rural California to photograph families preparing to leave, visiting several temporary assembly centers as they opened, and eventually highlighting Manzanar, the first of the permanent internment camps. Much of her work focused on the waiting and uncertainty involved in the removal: piles of luggage waiting to be sorted, families wearing identification tags while awaiting transport.[25] To many observers, her photograph[26] of Japanese American children pledging allegiance to the flag shortly before they were sent to camp is a haunting reminder of the travesty of detaining people without charging them with a crime.[27]

Her images were so obviously critical that the Army impounded most of them, and they were not seen publicly during the war.[28][29] Today her photographs of the internment are available in the National Archives on the website of the Still Photographs Division, and at the Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.

California School of Fine Arts/San Francisco Art Institute

In 1945, Ansel Adams invited Lange to teach at the first fine art photography department at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA), now known as San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). Imogen Cunningham and Minor White also joined the faculty.[30]

In 1952, Lange co-founded the photography magazine Aperture. In the mid-1950s, Life magazine commissioned Lange and Pirkle Jones to shoot a documentary about the death of Monticello, California and the subsequent displacement of its residents by the damming of Putah Creek to form Lake Berryessa. Because the magazine did not run the piece, Lange devoted an entire issue of Aperture to the work. The collection was shown at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1960.[31] Another series for Life magazine, begun in 1954 and featuring the lawyer Martin Pulich, grew out of Lange's interest in how poor people were defended in the court system, which by one account grew out of personal experience associated with her brother's arrest and trial.[32]

Death and legacy

In the last two decades of her life, Lange's health declined.[4] She suffered from gastric problems as well as post-polio syndrome, although the reoccurrence of the pain and weakness of polio was not yet recognized by most physicians.[6] Lange died of esophageal cancer on October 11, 1965, in San Francisco, California, at age seventy.[12][33] She was survived by her second husband, Paul Taylor, two children, three stepchildren,[34] and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Three months later, the Museum of Modern Art in New York mounted a retrospective of her work, which Lange herself had helped to curate.[35] It was MoMa's first one-person retrospective by a female photographer.[36] In February 2020, MoMA exhibited her work again, under the rubric “Dorothea Lange: Words and Pictures,"[37] prompting critic Jackson Arn to write that "the first thing" this exhibition "needs to do—and does quite well—is free her from the history textbooks where she’s long been jailed."[5] Contrasting her work with that of other 20th century photographers such as Eugène Atget and André Kertész whose images "were in some sense context-proof, Lange’s images tend to cry out for further information. Their aesthetic power is obviously bound up in the historical importance of their subjects, and usually that historical importance has had to be communicated through words." That characteristic has caused "art purists" and "political purists" alike to criticize her work, which Arn argues is unfair: "The relationship between image and story," Arn notes, was often altered by Lange's employers as well as by government forces when her work did not suit their commercial purposes or undermined their political purposes. In his review of this exhibition, critic Brian Wallis also stressed the distortions in the "afterlife of photographs" that went often contrary to Lange's intentions.[38] - Finally, Jackson Arn situates Lange's work alongside other Depression-era artists such as Pearl Buck, Margaret Mitchell, Thornton Wilder, John Steinbeck, Frank Capra, Thomas Hart Benton, and Grant Wood in terms of their role creating a sense of the national "We."[5]

In 2003, Lange was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[39] In 2006, an elementary school was named in her honor in Nipomo, California, near the site where she had photographed Migrant Mother.[40] In 2008, she was inducted into the California Hall of Fame, located at The California Museum for History, Women and the Arts; her son, Daniel Dixon, accepted the honor in her place.[41] In October 2018, Lange's hometown of Hoboken, New Jersey honored her with a mural depicting Lange and two other prominent women from Hoboken's history, Maria Pepe and Dorothy McNeil.[42]

Collections

- Kalamazoo Institute of Arts[43]

- Museum of Modern Art, New York[44]

- Whitney Museum of American Art[45]

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art[46]

References

- Hudson, Berkley (2009). Sterling, Christopher H. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Journalism. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE. pp. 1060–67. ISBN 978-0-7619-2957-4.

- Lurie, Maxine N. and Mappen, Marc. Encyclopedia of New Jersey. 2004, page 455

- Vaughn, Stephen L. Encyclopedia of American Journalism. 2008, page 254

- "Dorothea Lange – Photographer (1895–1965)". A&E Television Network. November 16, 2016. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- Arn, Jackson (March 5, 2020). "How Dorothea Lange Invented the American West". Forward. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- Dorothea, Lange (2014). Dorothea Lange. Gordon, Linda (Second ed.). New York City. ISBN 9781597112956. OCLC 890938300.

- "Corrina Wu, "American Eyewitness", CR Magazine, Spring/Summer 2010". Crmagazine.org. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- Acker, Kerry Dorothea Lange, Infobase Publishing, 2004

- Dorothea., Lange (1995). The photographs of Dorothea Lange. Davis, Keith F., 1952–, Botkin, Kelle A. Kansas City, Mo.: Hallmark Cards in association with H.N. Abrams, New York. ISBN 0810963159. OCLC 34699158.

- Durden, Mark (2001). Dorothea Lange (55). London N1 9PA: Phaidon Press Limited. p. 126. ISBN 0-7148-4053-X.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Dorothea Lange". NARA. Retrieved June 29, 2008.

Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, Dorothea Lange (1895–1965) announced her intention to become a photographer at age 18. After apprenticing with a photographer in New York City, she moved to San Francisco and in 1919 established her own studio.

- Oliver, Susan (December 7, 2003). "Dorothea Lange: Photographer of the People".

- Stienhauer, Jillian (September 2012). "Dorothea Lange". Art + Auction. 36: 129.

- Isaac, Frederick (1989). "Milestones in California History: The Grapes of Wrath: Fifty Years after". California History. 68 (3): 25462393. doi:10.2307/25462393. JSTOR 25462393.

- Perchick, Max. "’Dorothea Lange’ the Greatest Documentary Photographer in the United States." Photographic Society of America 61.6 (n.d.): June 1995. Web.

- Durden, p. 3.

- "Two women and a photograph". The Hindu.

- (Popular Photography, Feb. 1960)

- "Dorothea Lange ~ Watch Full Film: Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning". American Masters. PBS. August 30, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- Dunne, Geoffrey (2002). "Photographic license". New Times. Archived from the original on June 2, 2002.

- Rosler, Martha (2004). Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001. pp. 184.

- "Dorothea Lange". John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- "Hayward, California, Two Children of the Mochida Family who, with Their Parents, Are Awaiting Evacuation". World Digital Library. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- Civil Control Station, Registration for evacuation and processing. San Francisco, April 1942. War Relocation Authority, Photo By Dorothea Lange, From the National Archive and Records Administration taken for the War Relocation Authority courtesy of the Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley, California. Published in Image and Imagination, Encounters with the Photography of Dorothea Lange, Edited by Ben Clarke, Freedom Voices, San Francisco, 1997.

- Alinder, Jasmine. "Dorothea Lange". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- Pledge of allegiance at Rafael Weill Elementary School a few weeks prior to evacuation, April 1942. N.A.R.A.; 14GA-78 From the National Archive and Records Administration taken for the War Relocation Authority courtesy of the Bancroft Library. Published in Image and Imagination, Encounters with the Photography of Dorothea Lange, Edited by Ben Clarke, Freedom Voices, San Francisco, 1997.

- Davidov, Judith Fryer. Women's Camera Work. 1998, page 280

- Dinitia Smith (November 6, 2006). "Photographs of an Episode That Lives in Infamy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- Kerri Lawrence (February 16, 2017). "Correcting the Record on Dorothea Lange's Japanese Internment Photos". National Archives News. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- Robert Mix. "Vernacular Language North. SF Bay Area Timeline. Modernism (1930–1960)". Verlang.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- BellaVistaRanch.net. Suisun History. Nancy Dingler, Part 3 – Fifty years since the birth of the Monticello Dam. Retrieved on August 17, 2009.

- Partridge, Elizabeth (1994). Dorothea Lange–a visual life. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 26. ISBN 1-56098-350-7.

- "Dorothea Lange Is Dead at 70. Chronicled Dust Bowl Woes. Photographer for 50 Years Took Notable Pictures of 'Oakies' Exodus". The New York Times. October 14, 1965. Retrieved June 29, 2008.

- Neil Genzlinger (August 28, 2014). "The Story Behind the Photos". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- "American Masters – Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning". PBS, thirteen.org. August 29, 2014. Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- Partridge, Elizabeth. (November 5, 2013). Dorothea Lange, grab a hunk of lightning : her lifetime in photography. San Francisco. ISBN 9781452122168. OCLC 830030445.

- "Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "Dorothea Lange and the Afterlife of Photographs". Aperture Foundation NY. April 24, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "National Women's Hall of Fame: Dorothea Lange". womenofthehall.org. 2003. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- Mike Hodgson (May 6, 2016). "Lange Elementary's 10th anniversary comes with Gold Ribbon Award". Santa Maria Times. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- Timm Herdt (December 21, 2008). "Hall of Fame ceremony lauds state achievers in many fields". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- "Hoboken Celebrates New Mural on Northern Edge, Celebrating Inspirational Women of the Mile Square City". hNOW. October 26, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- "Inspired by Art : Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California | Kalamazoo Institute of Arts (KIA)". www.kiarts.org.

- "Dorothea Lange". The Museum of Modern Art.

- "Dorothea Lange". whitney.org.

- "Dorothea Lange | LACMA Collections". collections.lacma.org.

Further reading

- Dorothea Lange; Paul Schuster Taylor (1999) [1939]. An American Exodus: A record of Human Erosion. Jean Michel Place. ISBN 978-2-85893-513-0.

- Milton Meltzer (1978). Dorothea Lange: A Photographer's Life. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0622-2.

- Linda Gordon (2009). Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05730-0.

- Linda Gordon; Gary Y. Okihiro, eds. (2006). Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 0-393-33090-7.

- Linda Gordon (2003). Encyclopedia of the Great Depression. Gale. ISBN 9780028656861.

- Anne Whiston Spirn (2008). Daring to Look: Dorothea Lange's Photographs and Reports from the Field. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226769844.

- Sam Stourdze, ed. (2005). Dorothea Lange: The Human Face. Paris: NBC Editions. ISBN 9782913986015.

- Neil Scott-Petrie (2014). Dorothea Lange Color: Photography. CreateSpace. ISBN 9781495477157.

- Pardo, Alona (2018). Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing. Prestel. ISBN 9783791357768.

External links

- Oakland Museum of California – Dorothea Lange

- Dorothea Lange papers relating to the Japanese-American relocation, 1942–1974 (bulk 1942–1945), The Bancroft Library

- Online Archive of California: Guide to the Lange (Dorothea) Collection 1919–1965

- Dorothea Lange at the Museum of Modern Art

- Photo Gallery of Dorothea Lange at the library of congress

- Dorothea Lange – "A Photographers Journey", at Gendell Gallery

- 1964 Oral history interview with Lange

- Dorothea Lange Yakima Valley, Washington Collection, Great Depression in Washington State Project.

- Photographic Equality, by David J. Marcou, October 8, 2009.

- Encyclopædia Britannica

.jpg)