Doppelgänger (1969 film)

Doppelgänger is a 1969 British science-fiction film written by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson and Donald James and directed by Robert Parrish. Filmed by the Andersons' production company Century 21, it stars Roy Thinnes, Ian Hendry, Lynn Loring, Loni von Friedl and Patrick Wymark. Outside Europe, it was released as Journey to the Far Side of the Sun, the title by which it is now more commonly known. Set in 2069, the film concerns a joint European-NASA mission to investigate a newly-discovered planet that lies parallel to Earth on the other side of the Sun. The mission ends in disaster when one of the astronauts (Hendry) is killed, after which his colleague (Thinnes) realises that the planet is a mirror image of Earth.

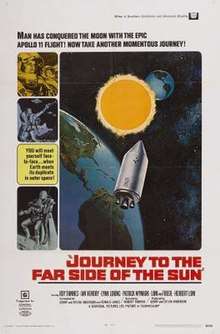

| Doppelgänger | |

|---|---|

Poster for the US release, with the alternative title Journey to the Far Side of the Sun | |

| Directed by | Robert Parrish |

| Produced by | Gerry and Sylvia Anderson |

| Screenplay by | Gerry and Sylvia Anderson Donald James Uncredited: Tony Williamson |

| Story by | Gerry and Sylvia Anderson |

| Starring | Roy Thinnes Ian Hendry Patrick Wymark |

| Music by | Barry Gray |

| Cinematography | John Read |

| Edited by | Len Walter |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | The Rank Organisation (UK) Universal Pictures (International) |

Release date | 27 August 1969 (US) 8 October 1969 (UK) |

Running time | 101 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

The first major live-action film to be produced by the Andersons – then best known for children's puppet television series such as Thunderbirds — Doppelgänger was shot between July and October 1968 at Pinewood Studios and on location in England and Portugal. The relationship between Parrish and the Andersons became strained as filming progressed, while creative disagreements between Gerry Anderson and his business partner John Read, the film's director of photography, led to Read's dismissal from Century 21. Although the Andersons wrote adult themes into the script in an attempt to distinguish Doppelgänger from their children's productions, cuts were needed to allow the film to be certified A by the British Board of Film Censors. Actors and props from the film were re-used during the production of the Andersons' first live-action TV series, UFO.

Doppelgänger premiered in August 1969 in the United States and October 1969 in the United Kingdom. While the film has been praised for its special effects and set design, some commentators have judged the parallel Earth premise to be clichéd and uninspired. Some of the plot devices and imagery have been viewed as poor pastiches of other science-fiction films, such as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). It has been described as a cult film.

Plot

In 2069, the European Space Exploration Council's (EUROSEC) Sun Probe discovers a planet orbiting the same path as Earth on the other side of the Sun. The probe's findings have been transmitted to a power in the East by double agent Dr Hassler. Security Chief Mark Neuman traces the messages to Hassler's laboratory and shoots him dead.

EUROSEC director Jason Webb convinces NASA representative David Poulson that the West must send a manned mission to the planet before Hassler's allies. NASA astronaut Colonel Glenn Ross and EUROSEC astrophysicist Dr John Kane are assigned to the mission. After undergoing training at the EUROSEC Space Centre in Portugal, Ross and Kane blast off in the spacecraft Phoenix. They go into hibernation for the outbound journey and are revived when they reach the planet three weeks later. Scans for extraterrestrial life prove inconclusive, so the astronauts decide to make a surface landing in their shuttle Dove. During the descent, Dove is damaged in a thunderstorm and crashes in mountainous terrain, seriously injuring Kane. The astronauts are picked up by a human rescue team, who tell Ross that they have landed near Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. When they are flown back to the Space Centre, it seems clear that they have somehow returned to Earth.

Neuman and EUROSEC official Lise Hartman question Ross, who denies that he aborted the mission. Kane dies from his injuries soon after. Eventually Ross realises that he is not on Earth, but has indeed reached the unknown planet — a Counter-Earth on which all aspects of life are mirror images of those on his Earth. Signs of this reversal include text printed backwards and cars being driven on the "wrong" side of the road. At first, Ross's wife Sharon and others around him refuse to accept his claims. However, Webb is convinced when Ross reads reflected text aloud without hesitation and Kane's post-mortem examination shows that his internal organs are on the "wrong" side of his body. Ross theorises that the two Earths are parallel and that the Ross of the Counter-Earth is experiencing similar events on the other side of the Sun. Webb proposes that Ross go back to Phoenix to retrieve its flight recorder, then return home.

EUROSEC builds a replacement for Dove designed to be compatible with the "reversed" technologies of Phoenix. Among the modifications is the reverse-polarisation of the electrical circuits. Ross blasts off in the spacecraft, which he has named Doppelganger, and attempts to dock with Phoenix. However, the electrical systems malfunction, disabling Doppelganger and causing it to fall through the atmosphere on a collision course with the Space Centre. EUROSEC is unable to repair the fault from the ground and Doppelganger crashes into a parked spacecraft. Ross is incinerated in the collision and the resulting chain reaction destroys much of the Space Centre, killing key personnel and destroying all records of Ross's presence on the Counter-Earth.

Years later, a wheelchair-bound Jason Webb has been admitted to a nursing home. Noticing his reflection in a mirror, he rolls forward to touch his image but crashes through the mirror and dies.[1]

Cast

|

Credited:

|

|

Uncredited:

|

|

Production

In the summer of 1967, during the filming of the Andersons' puppet series Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons, American film producer Jay Kanter travelled to London to establish a European production office for Universal Pictures.[2] Kanter was open to funding promising film ideas, so Lew Grade, the Andersons' employer and financial backer, set up a meeting for Gerry Anderson to pitch a story about a hypothetical "mirror" Earth.[2][3] On the film's inspiration, Anderson said: "I thought, rather naively, what if there was another planet the other side of the Sun, orbiting at exactly the same speed and the same size as Earth? That idea then developed into the planet being a replicated Earth and that's how it ended up, a mirrored planet."[3]

Writing

Assisted by Tony Williamson, Anderson and his wife Sylvia had written a 194-page treatment long before the initial meeting with Kanter.[2][4][5] Although they had planned it as a one-hour drama for Associated Television, Sylvia thought that the concept was "too good for a television play" and proposed making it as a feature film instead.[4] The title "Doppelgänger" was suggested by the Andersons' business partner John Read.[3] According to Gerry, the word "means 'a copy of oneself', and the legend goes that if you meet your doppelganger, it is the point of your death. Following that legend, clearly, I had to steer the film so that I could end it illustrating the meaning of that word."[3][6] Responding to claims that the tone is overly "dark", Anderson said that he wanted the film to have an interesting premise.[6]

Kanter was dissatisfied with the draft script, so Anderson hired novelist Donald James to improve the characterisation.[2] James' revisions included substantial changes to the parts of the story set on the mirror Earth, essentially causing the characters of Ross and Kane to switch roles.[3][7] In the Andersons' draft, Ross was blinded in the Dove crash while Kane survived unhurt; however, Kane's claims about a Counter-Earth led EUROSEC to declare him insane. A structural flaw in Doppelgänger caused it to burn up in the atmosphere with Kane trapped inside, and the film ended with Kane's wife, Jason Webb and the Rosses attending Kane's funeral.[7]

Despite James's efforts, Kanter remained unenthusiastic but agreed to finance the film on the condition that its director be subject to his approval.[2] After a ten-week search, the Andersons hired Robert Parrish, who had recently co-directed Casino Royale.[8] According to Gerry, Parrish "told us he loved the script and said it would be an honour to work with us. Jay Kanter gave Bob the thumbs up and we were in business."[1] He felt that while the commercial failure of Casino Royale raised questions about Parrish's ability, Doppelgänger could not have been made without him: "It wasn't a question of, 'Will we get on with him?' or, 'Is he the right man?' He was a name director, so we signed him up immediately."[8][9]

Casting

Leading the cast was Roy Thinnes as Colonel Glenn Ross of NASA. Gerry Anderson cast Thinnes after seeing his performance as David Vincent in the TV series The Invaders.[9] In the Andersons' draft script, Ross's first name was Stewart and he was the first man to have walked on Mars.[7] In a 2008 interview, Thinnes said of the film: "I thought [Doppelgänger] was an interesting premise, although now we know that there isn't another planet on the other side of the Sun, through our space exploration and telescopic abilities. But at that time it was conceivable, and it could have been scary."[10] To reflect the script's characterisation of Ross as a heavy smoker, Thinnes burned his way through many packets of cigarettes over the course of the production, damaging his health. In September 1969, The Age reported that the actor intended to demand a non-smoking clause in his next film contract, stating: "He smokes about two packets a day, but the perpetual lighting up of new cigarettes for continuity purposes was too much."[11]

Ian Hendry was cast as Dr John Kane, a British astrophysicist and head of the Phoenix project. In his biography, Anderson recalled that Hendry "was always drinking" and was visibly intoxicated while performing the Dove crash stunt sequences: "... he was pissed as a newt, and it was as much as he could do to stagger away. Despite all that, it looked exactly as it was supposed to on-screen!"[9][12] In the draft script, Kane's first name was Philip and he had a wife called Susan.[7] Scenes deleted from the finished film showed the character pursuing a romance with EUROSEC official Lise Hartman, portrayed by Loni von Friedl.[7]

Ross's wife Sharon was played by Lynn Loring. The role initially went to Gayle Hunnicutt, who quit early in the production after falling ill.[2] Her withdrawal led to the casting of Loring, Thinnes' then wife and star of the TV series The F.B.I..[2] Hunnicutt was to have appeared in a nude scene, written in to distinguish Doppelgänger from the Andersons' earlier productions.[9] In a 1968 interview in the Daily Mail, Anderson expressed a desire to change the public's perception of Century 21, saying that his company had been "typecast as makers of children's films".[9] On rumours that the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) would give the film an X certificate for mature content, he stated that it was Century 21's wish to "work with live artists doing subjects unsuitable for children."[9] The finished film replaced the nude scene with milder shots showing Sharon stepping into and out of a shower.[9] A subplot of the film concerns the Rosses' attempts to have a child and Glenn's discovery that Sharon has been taking birth control pills without his knowledge.[9] The draft script described Sharon as a United States Senator's daughter and saw her pursuing an affair with EUROSEC public relations officer Carlo Monetti.[7] In the finished film, the character, played by Franco De Rosa, is called Paulo Landi and appears only briefly, with the affair implied in one scene but not explored further.[9][13][14] In a scene deleted from the film, Glenn finds Paolo and Sharon in bed together at the Rosses' villa and throws them both into a swimming pool.[7]

Patrick Wymark played Jason Webb, the director of EUROSEC. Wymark was cast on the strength of his performance as John Wilder in the TV series The Plane Makers and The Power Game and was described in publicity material as "John Wilder (2069 model)".[12] Anderson said that Wymark's acting impressed him as much as Hendry's but that his hard drinking caused him to slur his lines on set.[12] He recalled that in one scene the actor "had to list these explanations ... and on take after take he couldn't remember that 'two' followed 'one'. We had to do it over and over again."[12] Anderson's biographers, Simon Archer and Marcus Hearn, characterise Wymark's portrayal of Webb as the dominant performance of the film.[12] The draft script described Webb as a British former Minister of Technology romantically involved with his secretary, Pam Kirby (played by Norma Ronald).[7]

The supporting cast included George Sewell as EUROSEC operations chief Mark Neuman (Mark Hallam in the draft script) and Ed Bishop as David Poulson, a NASA representative.[7] Originally Peter Dyneley was cast as Poulson, but he was replaced with Bishop as the producers felt that he looked too similar to Wymark and that scenes with both Poulson and Jason Webb would cause audiences to confuse the two characters.[2]

Filming

Filming began on 1 July 1968 at Pinewood Studios and ended on 16 October.[2] The crew used Neptune House in Borehamwood, Hertfordshire (now part of BBC Elstree Centre) to represent the exterior of the EUROSEC Headquarters and Heatherden Hall (part of the Pinewood complex in Iver Heath, Buckinghamshire) as the old Jason Webb's nursing home.[7] In September, the crew travelled to Albufeira, Portugal for location shooting.[2] After their arrival in the country, Marcelo Caetano succeeded the incapacitated António de Oliveira Salazar as prime minister.[2] Parrish was concerned that the political instability would cause shooting delays, so reduced the filming schedule from a month to two weeks.[2]

To create the illusion of a mirror Earth quickly and cheaply, the crew flipped the film negatives using a process called "flop-over".[2] This technique saved considerable time and money that would have been spent building "reversed" sets and props and organising road closures to shoot cars driving on the "wrong" side of the road.[2] However, it meant that scenes set on the Counter-Earth required careful planning and rehearsal with the cast and crew.[2] It also resulted in a number of continuity errors: for example, the "heart-lung-kidney" machines controlling Ross and Kane's vital functions aboard Phoenix are first shown connected to their left wrists, then their right.[7]

The crew had difficulty realising a scene depicting the EUROSEC board holding a videoconference on several high-resolution viewing monitors.[15] Due to the high cost of colour TV at the time of production and the need to avoid black and white to reflect the film's future setting, instead of using actual monitors the crew devised the scene by cutting screen-sized holes in a wall and placing the actors playing the conference delegates behind them.[15] Silver paper was added to reflect the studio lights and simulate a high-resolution image, with altered eyelines reinforcing the perception that each delegate is facing a camera instead of the other characters.[15] Archer and Hearn praise the videoconference scene as an example of how Anderson "proved once again that his productions were ahead of their time."[15]

As filming progressed, Anderson and Parrish came into conflict. According to Anderson, Kanter was brought in more than once to mediate: "[Sylvia and I] both knew how important the picture was to our careers, and we both desperately wanted to be in the big time."[16] At one point, Parrish refused to film a number of scenes, having decided that they were inessential to the plot.[16] When Anderson reminded Parrish of his contractual obligations, he announced to the cast and crew, "Hell, you heard the producer. If I don't shoot these scenes which I don't really want, don't need and will cut out anyway, I'll be in breach of contract. So what we'll do is shoot those scenes next!"[16] In his biography, Anderson said that his one regret about the film "[was] that I hired Bob Parrish in the first place."[16] Sylvia would later describe Parrish's direct as "uninspired. We had a lot of trouble getting what we wanted from him."[5]

Other scenes led to disagreements between the directors of Century 21: Gerry and Sylvia Anderson, Reg Hill and John Read, the film's director of photography.[15][17][18] For a scene depicting Lise Hartman (Loni von Friedl) taking a shower, Read did the lighting in silhouette as instructed by Parrish.[19] Gerry Anderson, who intended the scene to show Friedl nude, demanded a re-shoot, insisting that Read honour his obligations not just to Parrish as director but to him as producer.[19] According to Sylvia, "Gerry was very keen to show that he was part of the 'Swinging Sixties' and felt that seeing a detailed nude shot – as he visualised it – was more 'with it' than the more subdued version."[20]

Another dispute arose when Read filmed shots of the Phoenix spacecraft model using a hand-held camera. In his biography, Gerry recalled: "I knew enough about space travel to know that in a vacuum a spacecraft will travel as straight as a die ... [Parrish] told me that people were not familiar with space travel and therefore they would expect to see this kind of movement."[15][17] Read refused to re-shoot the scenes, stating that Parrish's instructions took precedence over Anderson's, and resigned from both the film and his position in Century 21 at the other directors' request.[19] Anderson elaborated: "Clearly John was in a difficult position. I do now understand how he must have felt, but in my heart I feel he couldn't play a double role."[17]

Effects

The film's special effects were produced at Century 21 Studios on the Slough Trading Estate under the direction of Derek Meddings.[2][16] More than 200 effects shots were filmed.[16] The design of the Phoenix spacecraft was based on the Saturn V rocket.[16] During filming, the six-foot-long (1.8 m) scale model unexpectedly caught fire and had to be completely rebuilt.[16] For realism, the launch sequence was shot in the studios' car park against an actual sky backdrop.[2][16]

Although Century 21 built a full-sized Dove module in Slough, they were prevented from using it at Pinewood Studios due to an agreement with the National Association of Theatrical Television and Kine Employees that props were not be transported.[15] The module was therefore destroyed, and although Pinewood carpenters built a replacement Anderson considered it inferior to the original.[15]

Commenting on the film's effects, Martin Anderson of the website Den of Geek describes the Phoenix command module as "beautifully ergonomic without losing too much NASA-ness" and the Dove lander as "a beautiful fusion of JPL gloss with classic lines".[21] He regards the Phoenix launch as Meddings' finest work prior to Moonraker (1979).[21] Archer and Hearn describe the sequence as "one of the most spectacular" of its kind produced by Century 21.[16]

Post-production

Composer Barry Gray, who wrote the music for all of Century 21's productions, said that his score for Doppelgänger was his favourite.[22] The score was recorded in three studio sessions between 27 and 29 March 1969.[17][23] The first of these sessions used a 55-member orchestra, the second 44 and the third 28.[23] The scenes of Ross and Kane's journey to the Counter-Earth are accompanied by a piece titled "Sleeping Astronauts" featuring an Ondes Martenot played by French ondiste Sylvette Allart.[22][23] Archer and Hearn describe this piece as "one of the most enchanting" ever written by Gray, adding that the soundtrack as a whole evokes a "traditional Hollywood feel" in contrast with the film's future setting.[17]

The title sequence, set inside double agent Dr Hassler's (Herbert Lom) laboratory, incorporates a spy theme focusing on the miniature camera hidden inside the character's false eye. Archer and Hearn consider this an imitation of the style of 1960s James Bond films.[12]

Distribution

_poster_art.jpg)

Distributors Universal Pictures were unenthusiastic with the finished film, causing its release to be delayed by a year.[7] On 26 March 1969, the British Board of Film Censors gave the film an A certificate.[2][9][24] To secure this rating, cuts to shots of contraceptive pills were required.[24][25] After premiering in the United States on 27 August 1969, the film had its UK opening at the Odeon Leicester Square on 8 October.[2][26] On 1 November, a second round of US openings began in Detroit, Michigan.[26] The general box office response was poor.[7]

In Europe, the film was distributed by The Rank Organisation under its original title.[17] It was renamed "Journey to the Far Side of the Sun" in the US and Australia after Universal judged that audiences in these countries might not know the meaning of the word "doppelganger".[17][27] Today, "Journey to the Far Side of the Sun" is the title by which the film is more commonly known.[17] Gerry Anderson biographers Simon Archer and Stan Nicholls argue that while it provides a clearer explanation of the plot, it lacks the "intrigue and even poetic quality of 'Doppelgänger'".[27]

Two original 35 mm prints of the film are known to exist.[28] One is kept by the British Film Institute and the other by Fanderson, the official Gerry Anderson fan club.[28] Whereas the Journey to the Far Side of the Sun format bills Roy Thinnes before Ian Hendry, in the original prints Hendry's name appears first.[7] Some British prints use an alternative version of the final scene that includes a brief voice-over from the deceased Ross, repeating a line of dialogue that Ross said to Jason Webb earlier in the film: "Jason, we were right. There are definitely two identical planets."[28]

Some TV broadcasts of the film have shown a flopped picture due to a mistake that was made while transferring one of the original prints to videotape in the 1980s: a telecine operator who was unfamiliar with the film believed that the scenes set on the Counter-Earth had been wrongly reversed and therefore inverted them to correct the supposed error.[28][27] A second flop-over was performed to restore the original image, which became the standard for all broadcasts but compromised the plot: when the film is shown in this form, the audience is led to believe that the Ross of the Counter-Earth has landed on the "normal" Earth.[27]

Previously available on LaserDisc, the film was released on DVD in Region 1 in 1998 and (in digitally-remastered form) in Regions 1 and 2 in 2008.[28][29] Prior to the 2008 release, the BBFC re-classified the film PG (from the original A) for "mild violence and language".[24] The filmed was released on Blu-ray in 2015.[30] The Australian Blu-ray release by Madman Entertainment includes a double-sided sleeve (enabling the film to be stored under either of its titles), a transfer of Fanderson's original film print and an exclusive audio commentary by Gerry Anderson.

Critical response

– Gerry Anderson's opinion of the film (1996 and 2002)[17][27]

Since its original release, Doppelgänger has attracted a mixed critical response. Archer and Nicholls consider it a cult film.[27]

Contemporary

In a review published in The Times, John Russell Taylor praised Doppelgänger as "quite ingenious" but suggested that the title and pre-release publicity had given away too much of the plot.[17] Judith Crist of New York magazine described it as "a science-fiction film that comes up with a fascinating premise three-quarters of the way along and does nothing with it."[31] She commended the film for being "nicely gadget-ridden", as well as raising questions about the conflict between science and politics, but criticised the editing.[31] Variety magazine considered the plot confusing, relating the crash of Dove to the quality of the writing: "Astronauts take a pill to induce a three-week sleep during their flight. Thereafter the script falls to pieces in as many parts as their craft."[32]

While The Miami News[33] and The Montreal Gazette[34] regarded the film as being better than average for its genre, the Pittsburgh Press dismissed it as "a churned out science-fiction yarn ... Let's hope there's only one movie like this one", and ranked it among the worst films of the year.[35] The Gazette added that while the film gets worse towards the end, "until then it's a reasonably diverting futuristic melodrama."[34] A review in the Southeast Missourian stated that "in today's space terminology [the film] almost rates as science – and pure reportage through film. Still it evolves as a fascinating motion-picture entertainment."[36] In his book A Pictorial History of Science Fiction Films (1975), Jeff Rovin called Doppelgänger "confusing but colourful" and commended its "superb" effects.[37]

Retrospective

Gary Gerani, co-writer of Pumpkinhead (1988), ranks the film 81st in his book Top 100 Sci-Fi Movies (2011), calling Doppelgänger "enigmatic" and a "fine example of speculative fantasy in the late '60s". He praises Thinnes' and Wymark's performances, the characterisation, the film's lesser themes (including adultery, infertility and corruption) and its "Fourth of July-style" special effects.[38] Sylvia Anderson suggested that American audiences, who were less familiar with Century 21's puppet productions than their British counterparts, were more enthusiastic about the film.[4] She explained: "It was all too easy to compare our real actors with our puppet characters and descriptions such as 'wooden', 'expressionless', 'no strings attached' and 'puppet-like' were cheap shots some of the UK critics could not resist ... Typecasting is the lazy man's friend, and boy were we typecast in Britain."[4] In 1992 she said of the film: "I saw it on TV a couple of years ago and I was very pleased with it. I thought it came over quite well."[39]

In a review for the website Den of Geek, Martin Anderson praises Parrish's direction and Meddings' effects but states that the film's "robust and prosaic" dialogue sits "ill-at-ease with the metaphysical ponderings". He also questions the editing, noting that many of the effects shots have "that 'Hornby' factor, slowing up the narrative unnecessarily". He rates Doppelgänger three stars out of five, summing it up as "an interesting journey with many rewards".[25] TV Guide magazine gives the film two stars out of four, calling it a "strange little film" with an "overwritten script".[40] To Chris Bentley, writer of episode guides on the Anderson productions, Doppelgänger is a "stylish and thought-provoking science-fiction thriller".[41]

Glenn Erickson of DVD Talk writes that Doppelgänger "takes an okay premise but does next to nothing with it. We see 100 minutes of bad drama and good special effects, and then the script opts for frustration and meaningless mystery." He criticises the cinematography, comparing it to that of the Andersons' puppet TV series Thunderbirds in so far as the characters "stand and talk a lot", while defining the script as "at least 60 percent hardware-talk and exposition ... How people move about – airplane, parachute, centrifuge – is more important than what they're doing." He also argues that the film wastes the opportunities presented by its parallel world concept in favour of being "an excuse to show cool rocket toys".[42]

The Film4 website gives Doppelgänger two-and-a-half stars out of five, praising the special effects and costume design but criticising the subplots about Dr Hassler's treachery and the Rosses' marital problems for being unnecessary distractions from the main plot. It also questions the originality of the premise and the depth of the writing: "Anderson's has to be the cheapest alternate Earth ever. Whereas audiences might expect a world where the Roman Empire never fell or the Nazis won World War II, here the shocking discovery is that people write backwards. That's it." It recommends the film to Anderson fans only, summing it up as "an occasionally interesting failure".[43] Gary Westfahl of the webzine SF Site judges the use of a near-perfect parallel Earth to be uninspired, describing the setting as "the most boring and unimaginative alien world imaginable".[44]

Interpretation

Archer and Nicholls cite among possible causes of the film's commercial failure its "quirky, offbeat nature" and the loss of public interest in space exploration after the Apollo 11 Moon landing.[27] The topic of the landing dominated a contemporary review in The Milwaukee Journal, which found similarities in the plot of Doppelgänger: "... the spacemen find a few bugs in their 'LM' and crash on the planet. And do they ever have their hands full in getting back to Earth!" Suggesting that the actors' performances are hampered by an excess of technical dialogue, the review concluded: "... the makers of this space exploiter may get lots of mileage at the box office, but Neil, Buzz and Mike did it better on TV."[45]

It has also been suggested that 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes, both released in 1968, set a high standard for other science-fiction films to follow.[17][42] Erickson argues that Doppelgänger is inferior to 2001 for depicting a "working future" where people remain attached to commercialism. Comparing the visual style to that of 2001, he notes similar use of "psychedelic" images and close-up shots of human eyes but adds that "all these borrowings are fluff without any deeper meaning." Film4's review describes the final scene featuring Webb as "hell-bent on recreating the enigmatic finale of 2001 by using a mirror, a wheelchair and a tartan blanket."[43] Rovin argues that Doppelgänger's effects "[occasionally] outshine" 2001's."[46] He goes on to state that the film "attempts to kindle a profundity similar to that of [2001] in its abstract philosophising about the dichotomy of dual worlds, but fails with a combination of meat-and-potatoes science fiction and quasi-profound themes."[47] He suggests that Doppelgänger is "neither a kid's film nor a cult film" but rules that "the elements that comprise the finished effort are more than individually successful."[47]

Martin Anderson compares Doppelgänger to other science-fiction films like Solaris (1972), identifying a "lyrical" tone to the dialogue. However, he concedes that Doppelgänger "doesn't bear comparison with Kubrick or [Solaris director] Tarkovsky."[25] Both commentator Douglas Pratt and the London Institute of Contemporary Arts compare the film to "The Parallel", an episode of The Twilight Zone in which an astronaut returns to Earth to find that his world bizarrely changed and concludes that he has entered a parallel universe.[48][49] Critic S. T. Joshi likens Doppelgänger's theme of duplication to the premise of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, in which a race of extraterrestrials called the "Pod People" kidnap humans and replace them with doppelgangers.[50]

Legacy

Despite the film's box office failure, Lew Grade awarded the Andersons further live-action commissions.[19] The first was UFO, Century 21's first live-action TV series, which debuted in 1970.[19] Doppelgänger is considered a precursor to UFO and has also been described as a "trial run" for the following series, Space: 1999.[28][51] UFO re-used many of Doppelgänger's costumes, props, shooting locations and music tracks.[52] Most of the film's cast went on to appear in the series – notably Ed Bishop in the lead role of Colonel Ed Straker and George Sewell as his deputy, Colonel Alec Freeman.[7] Recycled props included the filming models of Phoenix and Dove and some of film's futuristic cars and utility vehicles, modelled respectively on Ford Zephyr Zodiacs and Leyland Mini Mokes.[7][53] Neptune House, which appears as EUROSEC Headquarters in Doppelgänger, became the face of the Harlington-Straker Film Studios where the fictional SHADO organisation is based.[7] Also featured in UFO are Barry Gray's film score tracks "Sleeping Astronauts" and "Strange Planet", the latter accompanying the series' closing credits.[28] UFO's opening titles also imitated the teleprinter shots that formed the basis of Doppelgänger's title sequence.[54]

A retrospective published on the website IGN argues that the presentation of politics and economics in Doppelgänger goes against the conventions of 1960s science fiction.[51] This is reflected in UFO, whose characters "were constantly having to deal with the pressures of having to show progress under the scrutiny of accountants and elected officials, much the same way NASA was starting to in the US."[51] On the links between Doppelgänger and UFO, Martin Anderson makes another connection to director Stanley Kubrick: "... the most interesting common ground between the two projects remains the bleak ending(s) and the slight flirtation with the acid-induced imagery and mind fucks of 2001."[25]

See also

- Another Earth, a 2011 film with a similar premise

- The Stranger, a 1973 TV film with a similar premise

- Through the Looking-Glass, an 1871 novel that inverts many plot elements of its precursor, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

References

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 173.

- Bentley 2008, p. 306.

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 172.

- Anderson 2007, p. 65.

- Marcus, Laurence (October 2005). "Gerry Anderson: The Puppet Master – Part 3". teletronic.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Anderson, Martin (27 August 2008). "The Den of Geek Interview: Gerry Anderson". Den of Geek. London, UK: Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Bentley 2008, p. 307.

- Archer and Nicholls 1996, p. 136.

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 174.

- Harris, Will (24 May 2008). "A Chat with Roy Thinnes". premiumhollywood.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "Up in Smoke". The Age. Melbourne, Victoria: Fairfax Media. 18 September 1969. p. 25. ISSN 0312-6307. OCLC 222703030.

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 175.

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 193.

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 190.

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 177.

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 176.

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 178.

- La Rivière 2009, p. 188.

- La Rivière 2009, p. 189.

- Anderson 2007, p. 36.

- Anderson, Martin (15 July 2009). "Top 75 Spaceships in Movies and TV: Part 2". Den of Geek. London, UK: Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on 11 March 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Titterton, Ralph; Ford, Cathy; Bentley, Chris; Gray, Barry. "Barry Gray Biography" (PDF). lampmusic.co.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- de Klerk, Theo (25 December 2003). "Complete Studio-Recording List of Barry Gray". tvcentury21.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "BBFC Certifications for Doppelgänger". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Anderson, Martin. "Den of Geek Review". Den of Geek. London, UK: Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- American Film Institute Catalogue: Feature Films 1961–1970 (2nd ed.). Berkeley, California; Los Angeles, California; London, UK: University of California Press. 1997 [1976]. p. 560. ISBN 0-520-20970-2.

- Archer and Nicholls 1996, p. 138.

- "Feature Film Productions: Doppelgänger". Fanderson. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Wickes, Simon (26 June 2008). "Journey to the Far Side of the Sun DVD Released in US". tvcentury21.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "Journey to the Far Side of the Sun (Blu-ray)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- Christie, Judith (17 November 1969). "Movies: Brave Are the Lonely". New York. New York: New York Media Holdings. 2 (46): 64. ISSN 0028-7369. OCLC 1760010.

- "Variety Review". Variety. Los Angeles, California: Reed Business Information. 1 January 1969. ISSN 0042-2738. OCLC 1768958. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "Miami News Entertainment Guide". The Miami News. West Palm Beach, Florida: Cox Enterprises. 25 September 1969. p. 13. ISSN 1528-5758. OCLC 10000467.

- Stoneham, Gordon (22 April 1972). "Movie Week". The Montreal Gazette. Montreal, Quebec: Postmedia Network. p. 93. OCLC 44269305.

- "The Lively Arts". Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: E.W. Scripps Company. 28 December 1969. p. 50. OCLC 9208497.

- "On the Rialto Screen". Southeast Missourian. Cape Girardeau, Missouri: Naeter Bros. 65 (279): 9. 4 September 1970. ISSN 0746-4452. OCLC 10049209.

- Rovin 1975, p. 223.

- Gerani, Gary (2011). Top 100 Sci-Fi Movies. San Diego, California: IDW Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-60010-879-2.

- Turner, Steve. "Sylvia Anderson Interview (1992)". Supermarionation is Go!. Blackpool, UK: Super M Productions. OCLC 499379680. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "TV Guide Review". TV Guide. Radnor, Pennsylvania: Triangle Publications. ISSN 0039-8543. OCLC 1585969. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Bentley, Chris (2001). The Complete Book of Captain Scarlet. London, UK: Carlton Books. p. 114. ISBN 1-84222-405-0.

- Erickson, Glenn (2008). "DVD Savant Review". DVD Talk. Internet Brands. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "Film 4 Review". Film4. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Westfahl, Gary. "Gary Westfahl's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Film: Gerry Anderson". SF Site. Archived from the original on 14 September 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Waxse, Bennett F. (26 September 1969). "Journey Rides Apollo Coattails". The Milwaukee Journal. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Journal Communications. p. 39. ISSN 1082-8850. OCLC 55506548.

- Rovin 1975, p. 124.

- Rovin 1975, p. 127.

- Pratt, Douglas (2005). Doug Pratt's DVD: Movies, Television, Music, Art, Adult and More. UNET 2 Corporation. p. 1281. ISBN 1-932916-01-6.

- "Institute of Contemporary Arts Review". Institute of Contemporary Arts. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Joshi, S. T. (2007). Icons of Horror and the Supernatural: An Encyclopedia of Our Worst Nightmares. 1. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-313-33781-9.

- "Featured Filmmaker: Gerry Anderson". IGN. Ziff Davis. 3 September 2002. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 188.

- Archer and Nicholls 1996, p. 146.

- Archer and Hearn 2002, p. 192.

Works cited

- Anderson, Sylvia (2007). My Fab Years! Sylvia Anderson. Neshannock, Pennsylvania: Hermes Press. ISBN 978-1-932563-91-7.

- Archer, Simon; Hearn, Marcus (2002). What Made Thunderbirds Go! The Authorised Biography of Gerry Anderson. London, UK: BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-53481-5.

- Archer, Simon; Nicholls, Stan (1996). Gerry Anderson: The Authorised Biography. London, UK: Legend Books. ISBN 978-0-09-922442-6.

- Bentley, Chris (2008) [2001]. The Complete Gerry Anderson: The Authorised Episode Guide (4th ed.). London, UK: Reynolds & Hearn. ISBN 978-1-905287-74-1.

- La Rivière, Stephen (2009). Filmed in Supermarionation: A History of the Future. Neshannock, Pennsylvania: Hermes Press. ISBN 978-1-932563-23-8.

- Rovin, Jeff (1975). A Pictorial History of Science Fiction Films. Secaucus, New Jersey: Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0-8065-0263-2.

External links

- Doppelgänger on IMDb

- Doppelgänger at AllMovie

- Doppelgänger at Rotten Tomatoes

- Doppelgänger at the TCM Movie Database