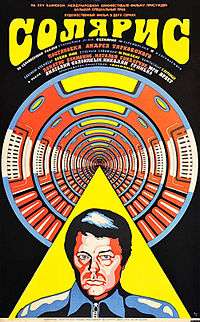

Solaris (1972 film)

Solaris (Russian: Солярис, tr. Solyaris) is a 1972 Soviet science fiction art film based on Stanisław Lem's novel of the same name published in 1961. The film was co-written and directed by Andrei Tarkovsky,[3][4] and stars Donatas Banionis and Natalya Bondarchuk. The electronic music score was performed by Eduard Artemyev; a composition by J.S. Bach is also employed.

| Солярис Solaris | |

|---|---|

Soviet film poster | |

| Directed by | Andrei Tarkovsky |

| Produced by | Viacheslav Tarasov |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Solaris by Stanisław Lem |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Eduard Artemyev |

| Cinematography | Vadim Yusov |

| Edited by | Lyudmila Feiginova |

| Distributed by | Mosfilm |

Release date |

|

Running time | 166 minutes[1] |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language |

|

| Budget | 1,000,000 SUR[2] (about $829,000 in 1972 USD) |

The plot centers on a space station orbiting the fictional planet Solaris, where a scientific mission has stalled because the skeleton crew of three scientists have fallen into emotional crises. Psychologist Kris Kelvin (Banionis) travels to the station in order to evaluate the situation, only to encounter the same mysterious phenomena as the others. The film was Tarkovsky's attempt to bring a new emotional depth to science fiction films; he viewed most western works in the genre as shallow due to their focus on technological invention.[5]

Solaris won the Grand Prix Spécial du Jury and the FIPRESCI prize at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for the Palme d'Or.[6] It is often cited as one of the greatest science fiction films in the history of cinema.[7][8] Some of the ideas Tarkovsky expresses in this film are further developed in his film Stalker (1979).[9]

Plot

Psychologist Kris Kelvin is being sent on an interstellar journey to evaluate whether a decades-old space station should continue to study the oceanic planet Solaris. He spends his last day on Earth with his elderly father and retired pilot Berton. Years earlier Berton had been part of an exploratory team at Solaris but was recalled when he described seeing a four-meter-tall child on the surface of the water. This was dismissed as a hallucination by a panel of scientists, but now that the remaining crew members are making similarly strange reports, Kris's skills are needed.

Upon his arrival at Solaris Station,[10][11] a scientific research station, none of the three remaining scientists bother to greet Kelvin, and he finds the space station in dangerous disarray. He soon learns that his friend among the scientists, Dr. Gibarian, has killed himself. The two surviving crewmen—Snaut and Sartorius—are uncooperative and evasive. Kelvin catches fleeting glimpses of others aboard the station who were not part of the original crew. He also finds that Gibarian left him a rambling, cryptic farewell video message, warning him about the station.

After a fitful sleep, Kelvin is shocked to find Hari, his late wife, in his sleeping quarters. She is unaware of how she got there. Terrified by her presence, Kelvin launches the replica of his wife into outer space. Snaut explains that the "visitors" began appearing after the scientists conducted radiation experiments using X-rays in a desperate attempt to understand the planet's nature.

That evening, Hari reappears in his quarters. This time Kelvin calmly accepts her and they fall asleep together in an embrace. Hari panics when Kelvin briefly leaves her alone in the room, and injures herself. But before Kelvin can give first aid, her injuries spontaneously heal before his eyes. Sartorius and Snaut explain to Kelvin that Solaris created Hari from his memories of her. The Hari present among them, though not human, thinks and feels as though she were. Sartorius theorizes that the visitors are composed of "neutrino systems" but that it might still be possible to destroy them through use of a device known as "the annihilator". Later, Snaut proposes beaming Kelvin's brainwave patterns at Solaris in hopes that it will understand them and stop the disturbing apparitions.

In time, Hari becomes independent and is able to exist away from Kelvin's presence. She learns from Sartorius that the original Hari had committed suicide ten years earlier. Sartorius, Snaut, Kelvin and Hari gather together for a birthday party, which evolves into a philosophical argument, during which Sartorius reminds Hari that she is not real. Distressed, Hari kills herself again by drinking liquid oxygen, only to painfully resurrect after a few minutes. On the surface of Solaris, the ocean begins to swirl faster into a funnel.

Kelvin becomes ill and goes to sleep. He dreams of his mother as a young woman, washing away dirt or scabs from his arm. When he awakens, Hari is gone; Snaut reads her farewell note, in which she describes how she petitioned the two scientists to destroy her. Snaut then tells Kelvin that since they broadcast Kelvin's brainwaves into Solaris, the visitors had stopped appearing and islands began forming on the planet surface. Kelvin debates whether or not to return to Earth or to remain with Solaris.

Kelvin meets with his father at their dacha. The camera zooms out to reveal that it is on an island in Solaris's ocean.

Cast

- Donatas Banionis as Kris Kelvin

- Vladimir Zamansky as Kelvin's voice

- Raimundas Banionis as young Kelvin

- Natalya Bondarchuk as Hari

- Jüri Järvet as Dr. Snaut

- Vladimir Tatosov as Snaut's voice

- Vladislav Dvorzhetsky as Henri Berton

- Nikolai Grinko as Kelvin's Father

- Olga Barnet as Kelvin's Mother

- Anatoli Solonitsyn as Dr. Sartorius

- Sos Sargsyan as Dr. Gibarian

- Aleksandr Misharin as Commissioner Shanahan

- Bagrat Oganesyan as Professor Tarkhe

- Tamara Ogorodnikova as Anna, Kelvin's Aunt

- Tatyana Malykh as Kelvin's Niece

- Vitalik Kerdimun as Berton's Son

- Yulian Semyonov as Conference Chairman

- Olga Kizilova as Dr. Gibarian's guest

- Georgiy Teykh as Professor Messenger

Production

Writing

In 1968 the director Andrei Tarkovsky had several motives for cinematically adapting Stanisław Lem's science fiction novel Solaris (1961). First, he admired Lem's work. Second, he needed work and money, because his previous film, Andrei Rublev (1966), had gone unreleased, and his screenplay A White, White Day had been rejected (in 1975 it was realised as The Mirror). A film of a novel by Lem, a popular and critically respected writer in the USSR, was a logical commercial and artistic choice.[12] Another inspiration was Tarkovsky's desire to bring emotional depth to the science-fiction genre, which he regarded as shallow due to its attention to technological invention; in a 1970 interview, he singled out Stanley Kubrick's 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey as "phoney on many points" and "a lifeless schema with only pretensions to truth".[13]

Tarkovsky and Lem collaborated and remained in communication about the adaptation. With Fridrikh Gorenshtein, Tarkovsky co-wrote the first screenplay in the summer of 1969; two-thirds of it occurred on Earth. The Mosfilm committee disliked it, and Lem became furious over the drastic alteration of his novel. The final screenplay yielded the shooting script, which has less action on Earth and deletes Kelvin's marriage to his second wife, Maria, from the story.[12] In the novel Lem describes science's inadequacy in allowing humans to communicate with an alien life form, because certain forms, at least, of sentient extra-terrestrial life may operate well outside of human experience and understanding. In the movie, Tarkovsky concentrates on Kelvin's feelings for his wife, Hari, and the impact of outer space exploration on the human condition. Dr. Gibarian's monologue (from the novel's sixth chapter) is the highlight of the final library scene, wherein Snaut says: "We don't need other worlds. We need mirrors". Unlike the novel, which begins with Kelvin's spaceflight and takes place entirely on Solaris, the film shows Kelvin's visit to his parents' house in the country before leaving Earth. The contrast establishes the worlds in which he lives – a vibrant Earth versus an austere, closed-in space station orbiting Solaris – demonstrating and questioning space exploration's impact on the human psyche.[14]

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

The set design of Solaris features paintings by the Old Masters. The interior of the space station is decorated with full reproductions of the 1565 painting cycle of The Months (The Hunters in the Snow, The Gloomy Day, The Hay Harvest, The Harvesters, and The Return of the Herd), by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, and details of Landscape with the Fall of Icarus and The Hunters in the Snow (1565). The scene of Kelvin kneeling before his father and the father embracing him alludes to The Return of the Prodigal Son (1669) by Rembrandt. The references and allusions are Tarkovsky's efforts to give the young art of cinema historical perspective, to evoke the viewer's feeling that cinema is a mature art.[15]

The film references Tarkovsky's 1966 film Andrei Rublev by having an icon by Andrei Rublev being placed in Kelvin's room.[16] It is the second of a series of three films referencing Rublev, the last being Tarkovsky's next film, The Mirror, which was made in 1975 and which references Andrei Rublev by having a poster of the film hung on a wall.[17]

The cast

Tarkovsky initially wanted his ex-wife, Irma Raush, to play Hari, but after meeting Swedish actress Bibi Andersson in June 1970, he decided that she was better for the role. Wishing to work with Tarkovsky, Andersson agreed to be paid in rubles. Nevertheless, Natalya Bondarchuk was ultimately cast as Hari. Tarkovsky had met her when they were students at the State Institute of Cinematography. It was she who had introduced the novel Solaris to him. Tarkovsky auditioned her in 1970, but decided she was too young for the part. He instead recommended her to director Larisa Shepitko, who cast her in You and I. Half a year later, Tarkovsky screened that film and was so pleasantly surprised by her performance that he decided to cast Bondarchuk as Hari after all.[18]

Tarkovsky cast Lithuanian actor Donatas Banionis as Kelvin, the Estonian actor Jüri Järvet as Snaut, the Russian actor Anatoly Solonitsyn as Sartorius, the Ukrainian actor Nikolai Grinko as Kelvin's father, and Olga Barnet as Kelvin's mother. The director had already worked with Solonitsyn, who had played Andrei Rublev, and with Grinko, who appeared in Andrei Rublev and Ivan's Childhood (1962). Tarkovsky thought Solonitsyn and Grinko would need extra directorial assistance.[19] After filming was almost completed, Tarkovsky rated actors and performances thus: Bondarchuk, Järvet, Solonitsyn, Banionis, Dvorzhetsky, and Grinko; he also wrote in his diary that "Natalya B. has outshone everybody".[20]

Filming

In the summer of 1970 the USSR State Committee for Cinematography (Goskino SSSR) authorized the production of Solaris, with a length of 4,000 metres (13,123 ft), equivalent to a two-hour-twenty-minute running time. The exteriors were photographed at Zvenigorod, near Moscow; the interiors were photographed at the Mosfilm studios. The scenes of space pilot Berton driving through a city were photographed in September and October 1971 at Akasaka and Iikura in Tokyo. The original plan was to film futuristic structures at the World Expo '70, but the trip was delayed. The shooting began in March 1971 with cinematographer Vadim Yusov, who also photographed Tarkovsky's previous films. They quarreled so much on this film that they never worked together again.[21][22] The first version of Solaris was completed in December 1971.

The Solaris ocean was created with acetone, aluminium powder, and dyes.[23] Mikhail Romadin designed the space station as lived-in, beat-up and decrepit rather than shiny, neat and futuristic. The designer and director consulted with scientist and aerospace engineer Lupichev, who lent them a 1960s-era mainframe computer for set decoration. For some of the sequences, Romadin designed a mirror room that enabled Yusov to hide within a mirrored sphere so as to be invisible in the finished film. Akira Kurosawa, who was visiting the Mosfilm studios just then, expressed admiration for the space station design.[24]

In January 1972 the State Committee for Cinematography requested editorial changes before releasing Solaris. These included a more realistic film with a clearer image of the future and deletion of allusions to God and Christianity. Tarkovsky successfully resisted such major changes, and after a few minor edits Solaris was approved for release in March 1972.[25]

Music

The soundtrack of Solaris features Johann Sebastian Bach's chorale prelude for organ Ich ruf' zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ, BWV 639, played by Leonid Roizman, and an electronic score by Eduard Artemyev. The prelude is the central musical theme. Tarkovsky initially wanted the film to be devoid of music and asked Artemyev to orchestrate ambient sounds as the score. The latter proposed subtly introducing orchestral music. In counterpoint to classical music as Earth's theme, is fluid electronic music as the theme for the planet Solaris. The character of Hari has her own subtheme, a cantus firmus based on Bach's music featuring Artemyev's music atop it; it is heard at Hari's death and at the story's end.[15]

Reception and legacy

Solaris premiered at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Grand Prix Spécial du Jury and was nominated for the Palme d'Or. In the USSR, the film premiered in the Mir film theater in Moscow on February 5, 1973. Tarkovsky did not consider the Mir cinema the best projection venue.[26] Despite the film's narrow release in only five film theaters in the USSR,[27] the film sold 10.5 million tickets.[28] Unlike the vast majority of commercial and ideological films in the 1970s, Solaris was screened in the USSR in limited runs for 15 years without any breaks, giving it cult status. In the Eastern Bloc and in the West, Solaris premiered later. In the United States, a version of Solaris that was truncated by 30 minutes premiered at the Ziegfeld Theatre in New York City on October 6, 1976.[29]

Although Lem worked with Tarkovsky and Friedrich Gorenstein in developing the screenplay, Lem maintained he "never really liked Tarkovsky's version" of his novel.[30] Tarkovsky wanted a film based on the novel but artistically independent of it, while Lem opposed any divergence of the screenplay from the novel. Lem went as far as to say that Tarkovsky made Crime and Punishment rather than Solaris, omitting epistemological and cognitive aspects of his book.[31] But Lem also said in an interview that he had only seen part of the finale, much later, after Tarkovsky's death.[32] Tarkovsky claimed that Lem did not fully appreciate cinema and expected the film to merely illustrate the novel without creating an original cinematic piece. Tarkovsky's film is about the inner lives of its scientists. Lem's novel is about the conflicts of man's condition in nature and the nature of man in the universe. For Tarkovsky, Lem's exposition of that existential conflict was the starting point for depicting the characters' inner lives.[33]

In the autobiographical documentary Voyage in Time (1983), Tarkovsky says he viewed Solaris as an artistic failure because it did not transcend genre as he believed his film Stalker (1979) did, due to the required technological dialogue and special effects.[34] M. Galina in the 1997 article Identifying Fears called this film "one of the biggest events in the Soviet science fiction cinema" and one of the few that do not seem anachronistic nowadays.[35]

A list of "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema" compiled by Empire magazine in 2010 ranked Tarkovsky's Solaris at No. 68.[36] In 2002, Steven Soderbergh wrote and directed an American adaptation of Solaris, which starred George Clooney.

Salman Rushdie has called Solaris "a sci-fi masterpiece", adding, "This exploration of the unreliability of reality and the power of the human unconscious, this great examination of the limits of rationalism and the perverse power of even the most ill-fated love, needs to be seen as widely as possible before it's transformed by Steven Soderbergh and James Cameron into what they ludicrously threaten will be 2001 meets Last Tango in Paris. What, sex in space with floating butter? Tarkovsky must be turning over in his grave."[37]

Film critic Roger Ebert reviewed the 1976 release for The Chicago Sun-Times, giving the film three out of four stars and writing, "Solaris isn't a fast-moving action picture; it's a thoughtful, deep, sensitive movie that uses the freedom of science fiction to examine human nature. It starts slow, but once you get involved, it grows on you.'[38] He added Solaris to his "Great Movies" list in 2003, saying he had initially "balked" at its length and pacing but later came to admire Tarkovsky's goals. "No director makes greater demands on our patience. Yet his admirers are passionate and they have reason for their feelings: Tarkovsky consciously tried to create art that was great and deep. He held to a romantic view of the individual able to transform reality through his own spiritual and philosophical strength."[39] Ebert later compared the 2011 film Another Earth to Solaris, writing that Another Earth "is as thought-provoking, in a less profound way, as Tarkovsky's Solaris, another film about a sort of parallel Earth".[40]

In an example of life imitating art, Natalya Bondarchuk (Hari) revealed in a 2010 interview that she fell in love with Tarkovsky during the filming of Solaris and, after their relationship ended, became suicidal. She claims that her decision was partly influenced by her role.[41]

Adam Curtis's 2015 documentary film Bitter Lake includes scenes from this film. The metaphor is that just as the planet influences the cosmonauts who try to influence the planet, there have been cross influences among Afghanistan and its Soviet, American and British invaders.

The film was selected for screening as part of the Cannes Classics section at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival.[42]

The film also has a "Certified Fresh" rating of 95% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 58 reviews with an average rating of 8.5 out of 10, with the consensus reading: "Solaris is a haunting, meditative film that uses sci-fi to raise complex questions about humanity and existence."[43]

Home media

Solaris was released on LaserDisc in Japan in 1986.[44]

On May 24, 2011, The Criterion Collection released Solaris on Blu-ray Disc.[5][45] The most noticeable difference from the previous 2002 Criterion DVD release[46] was that the blue and white tinted monochrome scenes from the film were restored.[47]

See also

References

- "SOLARIS (A)". British Board of Film Classification. April 16, 1973. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- Staff. "Solaris (1972)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- Lopate, Phillip. "Solaris: Inner Space". Criterion. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Le Cain, Maximilian. "Andrei Tarkovsky". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Lopate, Phillip. "Solaris". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- "Festival de Cannes: Solaris". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- "Blade Runner tops scientist poll". BBC News. August 26, 2004. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- "Top 10 sci-fi films". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- Solovyeva, O. N.; Oboturov A. B. (2002). "Genesis and a human in the work of Andrei Tarkovsky" (in Russian). Vologda State Pedagogical University. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- Lem, Stanislaw (1961). Solaris (ebook – 2011 English translation). Solaris Bill Johnston (translator). Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- Lem, Stanislaw; Tarkovsky, Andrei (1972). "Solaris – 1972 (film script – English subtitle times => "00:31:52,985" + "00:44:05,350" – [zipped SRT-file])". Solaris (1972 film). Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- Tarkovsky, Andrei; edited by William Powell (1999). Collected Screenplays. London: Faber & Faber.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Marshall, Colin. "Andrei Tarkovsky Calls Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey a 'Phony' Film 'With Only Pretensions to Truth'". Open Culture. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- Lem, Stanisław (November 2002). Solaris. Harvest Books. ISBN 978-0-15-602760-1.

- Artemyev, Eduard. Eduard Artemyev Interview (DVD). Criterion Collection.

- Jones, Jonathan (February 12, 2005). "Out of this world". The Guardian. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- Cairns, David (July 16, 2011). "Mirror". Electric Sheep. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- Bondarchuk, Natalya. Natalya Bondarchuk Interview (DVD). Criterion Collection.

- Tarkovsky, Andrei; transl. by Kitty Hunter-Blair (1991). Time Within Time: The Diaries 1970–1986. Calcutta: Seagull Books. pp. 5–6 (June 13, June 15 & July 11, 1970). ISBN 81-7046-083-2.

- Tarkovsky, Andrei; transl. by Kitty Hunter-Blair (1991). Time Within Time: The Diaries 1970–1986. Calcutta: Seagull Books. pp. 44–45 (December 4, 1970). ISBN 81-7046-083-2.

- Tarkovsky, Andrei; transl. by Kitty Hunter-Blair (1991). Time Within Time: The Diaries 1970–1986. Calcutta: Seagull Books. pp. 38–39 (July 12 & August 10, 1970). ISBN 81-7046-083-2.

- Yuji, Kikutake. "Solaris locations in Akasaka and Iikura, Tokyo". Archived from the original on December 10, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- Yusov, Vadim. Vadim Yusov Interview (DVD). Criterion Collection.

- Romadin, Mikhail. Mikhail Romadin Interview (DVD). Criterion Collection.

- Tarkovsky, Andrei; transl. by Kitty Hunter-Blair (1991). Time Within Time: The Diaries 1970–1986. Calcutta: Seagull Books. pp. 49–55 (January 12 & March 31, 1972). ISBN 81-7046-083-2.

- Tarkovsky, Andrei; translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair (1991). Time Within Time: The Diaries 1970–1986. Calcutta: Seagull Books. pp. 67–70 (January 29, 1973). ISBN 81-7046-083-2.

- Trondsen, Trond. "The Movie Posters: Solaris". Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- Segida, Miroslava; Sergei Zemlianukhin (1996). Domashniaia sinemateka: Otechestvennoe kino 1918–1996 (in Russian). Dubl-D.

- Eder, Richard (October 7, 1976). "Movie Review: Solaris (1972)". The New York Times.

- Lem, Stanisław. "Solaris". Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- S.Beres'. Rozmowy ze Stanislawem Lemem, Krakow, WL, 1987, s.133–135.

- Andrej Tarkovskij: Klassiker – Классик – Classic – Classico: Beiträge zum internationalen Tarkovskij-Symposium an der Universität Potsdam ; Band 1, 2016, ISBN 3869563516, p. 60.

- Illg, Jerzy; Leonard Neuger (1987). "Z Andriejem Tarkowskim rozmawiają Jerzy Illg, Leonard Neuger (The Illg_Neuger Tarkovsky Interview (1985))". Res Publica. Warsaw. 1: 137–160. Archived from the original on January 16, 2008. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- Tarkovsky, Andrei. Voyage in Time (DVD). Facets.

- Galina, M. S. (1997). "Strangers among us. Identifying fears" (PDF). Social Sciences and Modernity (in Russian). ecsocman.edu.ru. p. 160. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema". Empire.

- Rushdie, Salman. Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992–2002. New York: Random House, 2002, p. 335.

- https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/solaris-1976

- https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-solaris-1972

- Ebert, Roger (July 27, 2011). "Another Earth (PG-13)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- Pleshakova, Anastasia (March 31, 2010). "Natalya Bondarchuk: "After an affair with Tarkovsky I baptized"". Komsomolskaya Pravda. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- "Cannes Classics 2016". Cannes Film Festival. April 20, 2016. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- Solaris at Rotten Tomatoes

- "14 Posters: Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris (1972) - Dinca". August 4, 2010.

- "Solaris Blu-ray".

- "Solaris DVD – FAQ".

- Gallagher, Ryan (February 13, 2011). "Criterion Announces New Solaris DVD & Blu-ray For May 2011, Selling Current Stock At 65% Off".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Solaris (1972 film). |

- Solaris on IMDb

- Solaris at Rotten Tomatoes

- Solaris at AllMovie

- Video – Solaris - Russian Trailer (1:20) on YouTube.

- Video - Solaris - International Trailer (3:19) on YouTube

- Video – Solaris (divided into two parts) – Mosfilm site [Eng subs/click "cc"].

- Solaris: Inner Space an essay by Phillip Lopate at the Criterion Collection