Didcot

Didcot (/ˈdɪdkɒt, -kət/ DID-kot, -kət) is a railway town and civil parish in the ceremonial county of Oxfordshire and the historic county of Berkshire. Didcot is 15 miles (24 km) south of Oxford, 10 miles (16 km) east of Wantage and 15 miles (24 km) north west of Reading. The town is noted for its railway heritage, Didcot station opening as a junction station on the Great Western Main Line in 1844.

| Didcot | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

Didcot town centre, including the modern art installation The Swirl | |

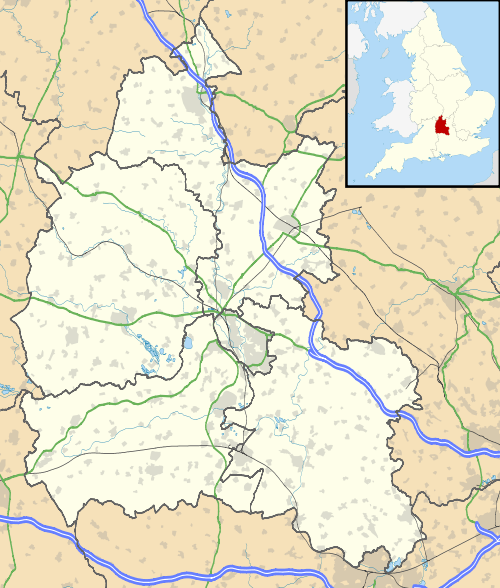

Didcot Location within Oxfordshire | |

| Area | 8.48 km2 (3.27 sq mi) |

| Population | 26,920 (2011 census)[1] |

| • Density | 3,175/km2 (8,220/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | SU525900 |

| • London | 54.7m |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Didcot |

| Postcode district | OX11 |

| Dialling code | 01235 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Oxfordshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Didcot Town Council |

Today the town is known for its railway museum and former power stations, and is the gateway town to the Science Vale: three large science and technology centres in the surrounding villages of Milton (Milton Park), Culham (Culham Science Centre) and Harwell (Harwell Science and Innovation Campus which includes the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory).

In 2017, researchers named Didcot as the most "normal" town in England.[2]

History

Ancient and Medieval eras

The area around present-day Didcot has been inhabited for at least 9,000 years. A large archaeological dig between 2010 and 2013 produced finds from the Mesolithic, Neolithic, Iron Age and Bronze Age.[3][4]

In the Roman era the inhabitants of the area tried to drain the marshland by digging ditches through what is now the Ladygrove area north of the town near Long Wittenham, evidence of which was found during surveying in 1994.[5] A hoard of 126 gold Roman coins dating from about AD 160 was found just outside the village in 1995 by an enthusiast with a metal detector. It is now displayed at the Ashmolean Museum on loan from the British Museum.[6][7]

The Domesday Book of 1086 does not record Didcot. In 13th-century records the toponym appears as Dudecota, Dudecote, Doudecote, Dudcote or Dudecothe. Some of these spellings continued into later centuries, and were joined by Dodecote from the 14th century onward, Dudcott from the 16th century onward and Didcott from the 17th century onward. It is derived from Old English, meaning the house or shelter of Dudda's people.[8][9] The name is believed to be derived from that of Dida, a 7th-century Mercian sub-king who ruled the area around Oxford and was the father of Saint Frithuswith or Frideswide, now the patron saint of both Oxford and Oxford University.[10]

Didcot was then a rural Berkshire village, and it remained so for centuries, only occasionally appearing in records. If Didcot existed at the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, it will have been much smaller than several surrounding villages, including Harwell and Long Wittenham, that modern Didcot now dwarfs. The nearest settlement recorded in the Domesday Book was Wibalditone, with 21 inhabitants and a church, whose name possibly survives in Willington's Farm on the edge of Didcot's present-day Ladygrove Estate.[11]

The oldest parts of the Church of England parish church of All Saints go back to the 12th century. They include the walls of the nave and east wall of the chancel, which were built about AD 1160.[12] The church is a Grade II* listed building.[13]

Early modern era

Parts of the original village survive in the Lydalls Road area around All Saints' church. In the 16th-century Didcot was a small village of landowners, tenants and tradespeople with a population of about 120.[14] The oldest surviving house in Didcot is White Cottage, a 16th-century timber-framed building in Manor Road that has a wood shingle roof. It is a Grade II listed building.[15]

At that time the village centre consisted of a group of cottages and surrounding farms around Manor, Foxhall and Lydalls Roads. Those still surviving include The Nook, Thorney Down Cottage and Manor Cottage, which were all built in the early to mid-17th century.[12] Didcot village was on the route between London and Wantage (now Wantage Road), which in 1752 was made a toll road. Didcot had three toll gates that collected revenue for the turnpike trust until 1879, when the trust was dissolved due to the growing use of the railway.[12]

19th and 20th centuries: Introduction of the Railway

Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway, engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, reached Didcot in 1839. In 1844 the Brunel-designed Didcot station was opened. The original station burnt down in the late 19th century. Although longer, a cheaper-to-build line to Bristol would have been through Abingdon farther north, but the landowner the first Lord Wantage is reputed to have prevented that alignment.[16] The railway and its junction to Oxford assisted the growth of Didcot. The station's name helped to standardise the spelling "Didcot".

Didcot, Newbury and Southampton Railway

Didcot's junction of the routes to London, Bristol, Oxford and to Southampton via the Didcot, Newbury and Southampton Railway (DN&S) made the town militarily important, especially during the First World War campaign on the Western Front and the Second World War preparations for D-Day. The DN&S line has since closed, and the large Army and Royal Air Force ordnance depots have disappeared beneath the power station and Milton Park Business Park; however the 11 Explosive Ordnance Disposal and Search Regiment RLC is still based at the Vauxhall Barracks in the town.

Remains of the DN&S railway survive in the eastern part of town. This line, designed to provide a direct link to the south coast from the Midlands and the North avoiding the indirect and congested route via Reading and Basingstoke, was built in 1879–82 after previous proposals had failed. It was designed as a main line and was engineered by John Fowler and built by contractors TH Falkiner and Sir Thomas Tancred, who together also constructed the Forth Railway Bridge.[17]

It was a very costly line to build due to the heavy engineering challenges of crossing the Berkshire and Hampshire Downs with a 1 in 106 gradient to allow for higher mainline speeds, and this initial cost and the initially lower than expected traffic volumes caused the company financial problems. It never independently reached Southampton, but instead joined the main London and South Western Railway line at Shawford, south of Winchester.

In the Second World War there was so much military traffic to the port of Southampton that the line was upgraded. The northern section between Didcot and Newbury was made double track. It was closed for 5 months in 1942–43 for this to be done. Several of the bridges in the area of Didcot and the Hagbournes were also strengthened and rebuilt.

Although passenger trains between Didcot and Newbury were withdrawn in 1962, the line continued to be used by freight trains for a further four years, and there was regular oil traffic to the north from the refinery at Fawley near Southampton. But in 1966 this traffic also was withdrawn, and the line was then dismantled. The last passenger train was a re-routed Pines Express in May 1964, diverted due to a derailment at Reading West. A section of the abandoned embankment towards Upton, now designated as a Sustrans route, has views across the town and countryside.[18]

21st century

As at 2011, Didcot had a population of more than 26,000.[1] The new town centre, the Orchard Centre, was opened in August 2005.[19] As part of the Science Vale Enterprise Zone, Didcot is surrounded by one of the largest scientific clusters in the United Kingdom. There are a number of major science and technology campuses nearby, including the Culham Science Centre, Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, and Milton Park.[20] The Diamond Light Source synchrotron, based at the Harwell Campus, is the largest UK-funded scientific facility to be built for more than 30 years.[21]

Didcot has been designated as one of the three major growth areas in Oxfordshire; the Ladygrove development, to the north and east of the railway line on the former marshland, is set to double the number of homes in the town since construction began in the late 1980s. Originally, the Ladygrove development was planned to be complete by 2001, but the plans for the final section to the east of Abingdon Road were only announced in 2006.

Before the Ladygrove development was completed, a prolonged and contentious planning enquiry decided that a 3,200-home development would be built to the west of the town, partly overlapping the boundary with the Vale of White Horse.[22] This is now being built as Great Western Park.

In 2008 a new £8 million arts and entertainment centre, Cornerstone, was opened in the Orchard Centre. It has exhibition and studio spaces, a café and a 236-seat auditorium. Designed by Ellis William Architects, the centre is clad with silvered aluminium panels and has a window wall, used to connect the building with passing shoppers.[23]

The United Kingdom government named Didcot a garden town in 2015, the first existing town to gain this status, providing funding to support sustainable and environmentally friendly town development over the coming 15 years.[24]

Railways

Didcot Railway Centre

Formed by the Great Western Society in 1967 to house its collection of Great Western Railway locomotives and rolling stock, housed in Didcot's 1932-built Great Western engine shed.[25] The Railway Centre is used as period film set and has featured in works including Anna Karenina, Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows and The Elephant Man.[26] The centre is north of Didcot Parkway railway station, and can be accessed from the station via the pedestrian subway.

Didcot Parkway station

The station was originally called Didcot but then renamed Didcot Parkway in 1985 by British Rail; the site of the old GWR provender stores, which had been demolished in 1976 (the provender pond was kept to maintain the water table) was made into a large car park to attract passengers from the surrounding area. An improvement programme for the forecourt of the station began in September 2012. This was viewed as being the first phase of better connecting the station to Didcot town centre.[27]

Economy

Power stations

Didcot A Power Station (between Didcot and Sutton Courtenay) ceased generating electricity for the National Grid in March 2013. Country Life magazine once voted the power station the third worst eyesore in Britain.[28]

The power station cooling towers were visible from up to 30 miles (48 km) away because of their location, but were designed with visual impact in mind (six towers in two separated groups 0.5 miles (800 m) apart rather than a monolithic 3×2 block), much in the style of what is sometimes called Didcot's 'sister' station – Fiddlers Ferry Power Station – at Widnes, Cheshire, constructed slightly earlier. The power station had also proved a popular man-made object for local photographers.

In October 2010, Didcot Sewage Works became the first in the UK to produce biomethane gas supplied to the national grid, for use in up to 200 homes in Oxfordshire.[29]

On Sunday 27 July 2014 three of the six 114-metre (374 ft) cooling towers were demolished in the early hours of the morning, using 180 kilograms (400 lb) of explosives. The demolition was streamed live by webcam.[30]

On Tuesday 23 February 2016, part of the boiler house building collapsed at Didcot Power Station; one person was declared dead, five injured and three missing. All were believed to have been preparing the site for demolition.[31] On Sunday 17 July 2016, what remained of the structure was demolished in a controlled explosion. The bodies of the three missing men were still in the remains at that time. A spokesman said that because of the instability of the structure, it had not been possible to recover the three bodies. For safety reasons, robots were used to place the explosive charges, and the site was demolished just after 6 o'clock in the morning (BST).

On Sunday 18 August 2019, the remaining three cooling towers were demolished at 7am.[32]

Car racing

Didcot has a strong connection with the Williams Grand Prix Engineering team as Frank Williams founded the team there in a former carpet warehouse in 1977.[33][34] After establishing themselves in Formula One, the factory, now including a small 'Williams Museum', moved within Didcot to a new factory on the Didcot A Power Station site on Basil Hill Road.[35] They stayed there until 1995 when they finally outgrew the site, moving to nearby Grove where they are based today. In 2012 a new road through the new Great Western Park development in Didcot was named Sir Frank Williams Avenue in honour of Williams' contribution to the town.[36]

Didcot also hosts a Pirelli distribution and logistics centre which provides tyres for Formula One Grand Prix motor racing events across Europe.[37][38] Didcot's link to the automotive industry continued in 2015 when the head offices of the Bloodhound SSC team were moved to the new University Technical College (UTC) Oxfordshire site on the boundary between Didcot and Harwell. The team are aiming to break the world land speed record with their supersonic car.[39]

Agriculture

Didcot is surrounded by farmland which has historically grown traditional British crops such as wheat and barley, sheep farming is also common in the area.[40] The area is also noted for farmers growing opium poppies for legal production of morphine and heroin to meet National Health Service demand.[41][42] The poppies produced are sold to Macfarlan Smith, a major pharmaceutical company, who hold a licence from the United Kingdom Home Office.[43]

Military

The British Army's Vauxhall Barracks is on the edge of town. The regimental headquarters of 11 Explosive Ordnance Disposal and Search Regiment RLC is based in the town.[46]

Local government and representation

Until 1974 Didcot was in Berkshire, but was transferred to Oxfordshire in that year, and from Wallingford Rural District to the district of South Oxfordshire, becoming the largest town in the new district. Didcot is also the largest town in the parliamentary constituency of Wantage, which has been represented since 2019 at Westminster by David Johnston, Conservative.

Didcot is a parish but has the status of a town. It is administered by Didcot Town Council, which comprises 21 councillors representing the six wards in the town:

- All Saints – 5 members

- Ladygrove – 7 members

- Milbrook – 1 member

- Northbourne – 4 members

- Orchard – 1 member

- Park – 3 members

Health

The district in England with the highest healthy life expectancy, according to an Office for National Statistics (ONS) study, is the 1990s-built Ladygrove Estate in Didcot.[47] While the average UK healthy lifespan was thought to be 68.8 for women and 67 for men in 2001, people in Ladygrove district of Didcot could expect 86 healthy years. It is believed Ladygrove may have benefited from the local recreation grounds and sports centre.[47][48]

Education

Didcot is served by six primary schools: All Saints' C of E, Ladygrove Park, Manor, Northbourne C of E, Stephen Freeman and Willowcroft. Along with these 6 schools based in Didcot, a further 7 local village schools form the Didcot Primary Partnership: Blewbury Endowed C of E, Cholsey, Hagbourne, Harwell Community, Long Wittenham C of E and South Moreton County.

There are two state-funded secondary schools in Didcot: St Birinus School and Didcot Girls' School are single-sex schools that join together at sixth form. Recently, another two secondary schools have opened; UTC, in 2015, and Aureus School, in 2017.

Arts and culture

Cornerstone, a new 278-seater multi-purpose arts centre, was opened on 29 August 2008.[49]

Didcot Choral Society, founded in 1958, performs three concerts a year in various venues around the town as well as an annual tour (Paris in 2008, Belgium in 2009).[50]

Didcot Concert Orchestra, founded in 2017, performs three concerts a year at Cornerstone.[51]

In November 2018, Rebellion Developments began setting up a new studio on the edge of Didcot, valued at $100 million, using the existing former Daily Mail printing works on Milton Road. The studio is planned to be used for film and TV series based on 2000 AD comic series characters, including Judge Dredd: Mega City One.[52]

Sport and leisure

Didcot Town Football Club's home ground is the Draycott Engineering Loop Meadow Stadium on the Ladygrove Estate, having moved from their previous pitch off Station Road in 1999 to make way for the new supermarket development. The club currently play in the 8th tier of the English Football League system. Most notable achievements include winning the FA Vase in 2005 and reaching The FA Cup 1st Round in 2015.

Didcot has three main leisure centres: Didcot Leisure Centre,[53] Didcot Wave Leisure Pool[54] and Willowbrook Leisure Centre.[55]

Didcot has its own chapter of the Hash House Harriers.[56] The club started in 1986 (the first run was on 8 April of that year).

Didcot Cricket Club's current home ground is at Boundary Park in Great Western Park.[57]

Didcot Dragons Korfball club was founded in 2003. The club has two teams in the Oxfordshire leagues. They train in Willowbrook Leisure Centre in winter and Boundary Park in summer.[58]

Didcot Phoenix cycle club[59] was founded in 1973 and is represented by over 70 members who participate in a range of cycling activities including touring, time trials, road racing, Audax, cyclocross and off-road events.

The Didcot & District Table Tennis Association (DDTTA) was established in 1949 to promote the playing of table tennis in the Didcot area. It organises an annual league competition containing affiliated teams from towns and villages across south Oxfordshire.[60]

Didcot Runners is an AAA affiliated running club that meets every Tuesday & Thursday for group runs and fitness sessions at Didcot Town Football Club. Its members participate in running races across the country.[61]

The OVO Energy Women's Tour, a road cycling event, passed through Didcot on 12 June 2019.[62] The race was halted for around 30 minutes on the Broadway because of a crash that caused the withdrawal of race leader Marianne Vos.[63]

Parks, gardens and open spaces

Didcot Town Council maintains the following:[64]

- Edmonds Park

- Loyd Recreation Park

- Smallbone Recreation Park

- Garden of Remembrance

- Marsh Recreation Ground

- Great Western Drive Park

- Ladygrove Park and Lakes

- Ladygrove woods

- Ladygrove Skate Park

- Mendip Heights Play Area

- The Diamond Jubilee Garden

- Broadway Gardens

- Stubbings Land

- Millennium wood at the Hagbourne Triangle

- Cemetery, Kynaston Road

Didcot also has a nature reserve, Mowbray Fields, where wildlife including common spotted orchid and Southern Marsh Orchid occur.[65].

Notable people

Didcot was the birthplace of William Bradbery, the first person to cultivate watercress commercially in the early 19th century.[66] Didcot is also the birthplace of former Reading and Oxford United manager Maurice Evans and one of Reading's most-capped football players Jerry Williams.[67] Didcot-born rower Ken Lester competed in the 1960 Summer Olympics at the age of 13 in the coxed pairs (as the cox), he remains Britain's youngest ever male Olympian.[68][69] Figurative artist Rodney Gladwell was also born in the town in 1928.[70] Air Commodore Russell La Forte CBE ADC was born in Didcot in 1960 and was commander of British armed forces in the South Atlantic Islands between 2013–15. He was a member of the Didcot Air Training Corps (Air Cadets) as a child.[71][72]

Matt Richardson, a comedian and television presenter known for hosting The Xtra Factor, grew up in Didcot.[73][74][75] The band Radiohead are from nearby Abingdon and recorded many tracks from their discography in a converted apple shed on the edge of Didcot, near the power station site.[76] This included a number of tracks from OK Computer that has appeared frequently in critic's lists of the greatest albums of all time.[77][78][79]

In popular culture

Didcot's synonymous connection with railways was noted in Douglas Adams and John Lloyd's humorous book the Meaning of Liff, published in 1983. The book, a "dictionary of things that there aren't any words for yet", referred to "a Didcot" as "The small, oddly shaped bit of card which a ticket inspector cuts out of a ticket with his clipper for no apparent reason".[80]

Didcot is referred to in Ricky Gervais' comedy feature film David Brent: Life on the Road: the song "Lady Gypsy" on the film's soundtrack tells of a romantic meeting "by the lakeside, just south of Didcot".[81]

An electricity pylon on farmland alongside Abingdon Road (opposite Tamar Way) on the eastern edge of Didcot featured on the cover of US rock band Black Swan Lane's album Under My Fallen Sky, released in November 2017.[82]

Nearby places

References

- "Didcot (Oxfordshire, South East United Kingdom)". City Population. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "'Most normal' town in England unveiled". BBC News. 29 March 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- Ffrench, Andrew. "Dig discovers 9,000-year-old remains at Didcot". Oxford Mail. Newsquest. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- Williams, Eleanor. "Didcot dig: A glimpse of 9,000 years of village life". BBC News. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- "Ladygrove Estate Archaeological Evaluation, Oxford Archaeological Unit" (PDF). The Human Journey. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- "Inside the Ashmolean". Oxford Mail. Newsquest. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- "Didcot Hoard". British Museum. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Ekwall 1960, Didcot

- Skeat 1911, p. 26.

- Vincent 1919, p. 67.

- "Willington". Open Domesday. University of Hull. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Lingham 2014

- Historic England. "Church of All Saints (Grade II*) (1047918)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- "Didcot The Essential Guide". Issuu. Issuu Digital Publishing. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Historic England. "White Cottage (Grade II) (1368767)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Lingham 1992

- Sands 1971, pp. 6–7.

- "Didcot, Wantage and The Ridgeway – Map". Sustrans. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Oxfordshire's Big Apple". The Orchard Centre. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Science Vale Information Sheet" (PDF). Science Vale. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- "Diamond facility starts to shine". BBC News. 14 July 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- "Page not found". South Oxfordshire District Council.

- "Didcot receives new arts centre". World Architecture News. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- "New garden towns to create thousands of new homes". Gov.uk. United Kingdom Government. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Lyons 1972, pp. 70–71

- "Didcot is 'most normal town in England', researchers claim". BBC News. BBC. 10 May 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Didcot Station – Latest Developments – South Oxfordshire District Council". South Oxfordshire District Council. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Britain's Worst Eyesores". BBC News. 13 November 2003. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Shah, Dhruti (5 October 2010). "Oxfordshire town sees human waste used to heat homes". BBC News. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- "Didcot power station towers demolished". BBC Oxford News. 27 July 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- "Didcot power station: one dead and three missing after building collapse". The Guardian. 23 February 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "Power cut as power station towers demolished". 18 August 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Williams still fighting at 600". Reuters. 29 June 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Williams Grand Prix Engineering". Motorsport Magazine. December 1979. Retrieved 18 March 2016. page 29

- "Williams' Old HQ at Didcot". The Williams Grand Prix Database. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Formula One's 'Sir Frank Williams Avenue' is unveiled". BBC News. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- "The British Grand Prix from a tyre point of view". Pirelli. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "Pirelli special feature - Cracking the barcode". Motorsport.com. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Ballinger, Alex (28 October 2015). "1,000mph world record rocket car team moves into Oxfordshire headquarters". Oxfordshire Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Farms Around Didcot". Domesday Project 1986. BBC. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- Duthel, Heinz (February 2015). Illegal drug trade – The War on Drugs. Books on Demand.

- Heyer; Harris-White (2009). The Comparative Political Economy of Development: Africa and South Asia. Routledge. p. 197. ISBN 9781135171940. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- Ffrench, Andrew (September 2013). "Farmers go into legal drug business with poppy crops". Oxford Mail. Newsquest. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- Associated Newspapers to build new print plant Daily Mail & General Trust 27 June 2005

- Didcot closure costs to reach almost 50m PrintWeek 1 December 2016

- "Vauxhall Barracks, Didcot, Oxfordshire, OX11 7EG". Completelytradeandindustrial.co.uk. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Regional health gap 'is 30 years'". BBC News. 9 September 2007. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- "Didcot: Where to enjoy a long healthy life". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- "Doors thrown open at the £7.4m arts centre". Didcot Herald. Newsquest. 22 August 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- "Didcot Choral Society". Didcot Choral Society. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Didcot Concert Orchestra :: About us". www.didcotconcertorchestra.org.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Stewart Clarke (24 November 2018). "Judge Dredd Owner Rebellion Sets Up $100 Million U.K. Film and TV Studio (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Welcome to Didcot Leisure Centre". Better.org.uk. 1 July 2008. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Welcome to Didcot Wave". Better.org.uk. 1 July 2008. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Willowbrook Leisure Centre". Soll-leisure.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 May 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Didcot Hash House Harriers". Didcoth3.org. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Didcot Cricket Club Blog". Didcot Cricket Club. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "Didcot Dragons Korfball". Didcot Dragons Korfball Club. 1 June 2018.

- "Didcot Phoenix Cycle Club".

- "Didcot & District Table Tennis Association".

- "Didcot Runners".

- cdowley (16 February 2017). "Stage Three". The OVO Energy Women's Tour. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Cary, Tom (12 June 2019). "Multi-rider pileup on stage three of Women's Tour forces leader Marianne Vos to abandon race". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "Parks Gardens and Lakes". Didcot.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- "Olympic summer for orchids". Newsletter. Earth Trust. p. 2.

- "Man about towns: Comedian Mark Steel reveals why British towns are anything but boring". The Independent. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- "Profile". Post War English & Scottish Football League A – Z Player's Database.

- Evans, Hilary; Gjerde, Arild; Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill; et al. "Ken Lester Olympic Results". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- "Britain's youngest Olympians". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Spalding 1990, p. 207.

- Allen, Emily (18 December 2007). "Airman to serve the Queen". Oxford Mail. Newsquest. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- "Trading places" (PDF). Royal Air Force News. 26 April 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- Richardson, Matt (24 January 2013). "Hello. I'm Matt". Matt Richardson Comedy. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- Moorin, Callum (26 September 2012). "Interview with Matt Richardson". cmoorin.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- Duff, Seamus (29 August 2013). "Simon Cowell proudly announces X Factor series 10 – but forgets Matt Richardson's name". Metro News. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- "NEW YORKE STORIES: ON THE TRAIL OF RADIOHEAD". Citizen Insane. Melody Maker. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Doyle, Tom (April 2008). "The Complete Radiohead". Q.

- Footman 2007

- "162 OK Computer – Radiohead". Rolling Stone. 2004. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Adams & Lloyd 1983, p. 39.

- Herring, Naomi (1 July 2016). "Ricky Gervais character sings about Didcot in latest trailer for The Office film". Oxford Mail. Newsquest. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- Williams, Tom (17 November 2017). "Didcot pylon becomes unlikely cover star for US rockers' new album". Oxford Mail. Newsquest. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

Bibliography

- Adams, Douglas; Lloyd, John (1983). The Meaning of Liff. London: Pan Books. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-330-28121-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ekwall, Eilert (1960) [1936]. Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Didcot. ISBN 0198691033.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Footman, Tim (2007). Welcome to the Machine: OK Computer and the Death of the Classic Album. Chrome Dreams. ISBN 978-1-84240-388-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lingham, Brian (1979). The Long Years of Obscurity. A History of Didcot. One – to 1841. Didcot: BF Lingham. ISBN 978-0-9506545-0-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lingham, Brian (1992). Railway Comes to Didcot: A History of the Town. 2 – 1839 to 1918. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7509-0092-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lingham, Brian (2000). A Poor Struggling Little Town: A History of Didcot. 3 – 1918 to 1945. Didcot: Didcot Town Council.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lingham, Brian (2014). Didcot Through Time. Gloucester: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445636047.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lyons, ET (1972). An Historical Survey of Great Western Engine Sheds: 1837–1947. Oxford Publishing. ISBN 086093019X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Page, William; Ditchfield, PH, eds. (1923). "Didcot". A History of the County of Berkshire. Victoria County History. III. assisted by John Hautenville Cope. London: The St Katherine Press. pp. 471–475.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1966). Berkshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 127–128.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sands, TB (1971). The Didcot, Newbury & Southampton Railway. The Oakwood Library of Railway History. Oakwood Press. pp. 6–7. OL28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skeat, Walter W (1911). The Place Names of Berkshire (1 ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spalding, Frances (1990). 20th Century Painters and Sculptors. Dictionary of British Art. 6. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 207. ISBN 978-1851491063.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vincent, James Edmund (1919). Highways and Byways in Berkshire (1 ed.). London: MacMillan & Co. p. 67.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Didcot. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Didcot. |