David Sharp (mountaineer)

David Sharp (15 February 1972 – 15 May 2006) was an English mountaineer who died near the summit of Mount Everest.[2] His death caused controversy and debate, because he was passed by a number of other climbers heading to and returning from the summit as he was dying,[3][4] although a number of others tried to help him.[3]

David Sharp | |

|---|---|

| Born | 15 February 1972 Harpenden, England |

| Died | 15 May 2006 (aged 34) Mount Everest, Nepal |

| Cause of death | Hypothermia or cerebral oedema |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Prior Pursglove College[1] the University of Nottingham, |

| Occupation | Mountaineer Mathematics teacher |

| Height | 5 ft 11 in (180 cm) |

.jpg)

Sharp had previously summitted Cho Oyu[5] and was noted as being a talented rock climber, who seemed to acclimatize well, and was known for being in good humor around mountaineering camps.[6] He had appeared briefly in season one of the television show Everest: Beyond the Limit, which was filmed the same season as his ill-fated expedition to Everest.[7]

He had a degree from the University of Nottingham and pursued climbing as a hobby.[6] He had worked for an engineering firm and took time off to go on adventures and climbing expeditions,[1] but had been planning to start work as a school teacher in the autumn of 2006.[6]

Early life

David Sharp was born in Harpenden, near London, and later attended Prior Pursglove College and the University of Nottingham.[8] He graduated with a Mechanical Engineering degree in 1993.[8] He worked for the Global security company QinetiQ.[1] In 2005 he quit this job and took a teacher training course, and was planning to start work as a teacher in the autumn of 2006.[8] David Sharp was also an experienced and accomplished mountaineer, and had climbed some of the world's tallest mountains including Cho Oyu in the Himalayas. Sharp did not believe in using a guide for mountains he was familiar with, local climbing assistance or artificial enhancements, such as high altitude drugs or supplementary oxygen, to reach the top of a mountain.[5]

Expeditions and summits

Mountaineering summary

While growing up in England, Sharp climbed Roseberry Topping.[3] At university, he was a member of the Mountaineering Club.[3]

Sharp also took a six-month sabbatical from his job to go on a backpacking trip through South America and Asia.[1][9]

In May 2002, Sharp summited the 8,200 m (26,903 ft) Cho Oyu with Jamie McGuinness and Tsering Pande Bhote.[10] Cho Oyu is the sixth highest peak in the world and is near Mount Everest.[9] The leader of the Cho Oyu expedition, impressed with Sharp's strength, acclimatization abilities, and rock climbing talent, invited him to join an expedition to Everest the next year.[9]

2001 Gasherbrum II expedition

In 2001, Sharp went on an expedition to Gasherbrum II, an 8,035 m (26,362 ft) mountain located in the Karakoram, on the border between Gilgit–Baltistan province, Pakistan, and Xinjiang, China.[11] The expedition, led by Henry Todd, did not summit due to bad weather.[11]

2002 Cho Oyu expedition

In 2002, Sharp went on an expedition to Cho Oyu, an 8,201 m (26,906 ft) peak in the Himalayas, with a group led by Richard Dougan and McGuinness of the Himalayan Project.[11] They did make it to the summit, but one member died from falling into a crevasse; this opened up a slot on the group's trip to Everest the next year.[11] Dougan regarded Sharp as a strong climber, but noted that he was tall and skinny, possessing a light frame with little body fat; in cold-weather mountaineering, body fat can be critical to survival.[11][12]

2003 Mount Everest expedition

Sharp's first Mount Everest expedition was in 2003 with a group led by British climber Richard Dougan.[13] The party also included Terence Bannon, Martin Duggan, Stephen Synnott, and McGuinness. Only Bannon and McGuinness reached the summit, but the group incurred no fatalities.[13] Dougan noted that Sharp had acclimatized well and was their strongest team member.[6] In addition, Sharp was noted for being a pleasant person at camp and had a talent for rock climbing.[6] However, when Sharp started to get frostbite on the group's ascent, most of the group agreed to turn back with him from the summit.[6]

Dougan and Sharp helped a struggling Spanish climber who was heading up at that time, and gave him some extra oxygen.[6] Sharp lost some of his toes to frostbite on this climb.[6]

2004 Mount Everest expedition

In 2004, Sharp joined a Franco-Austrian expedition to the north side of Mount Everest,[11] climbed to 8,500 m (28,000 ft), but did not reach the summit.[13] Sharp could not keep up with the others and stopped before the First Step.[11] The expedition's leader was Hugues d’Aubarede, a French climber who was later killed in the 2008 K2 disaster (his third attempt to climb that mountain),[14] but who became, on this 2004 expedition, the 56th French person to summit Everest.[14] D'Aubarede's group reached the summit on the morning of 17 May[15] and included Austrians Marcus Noichl, Paul Koller, and Fredrichs "Fritz" Klausner as well as Nepalis Chhang Dawa Sherpa, Lhakpa Gyalzen Sherpa, and Zimba Zangbu Sherpa (also known as Ang Babu).[15][16] When Sharp died in 2006, d'Aubarede was on an expedition to K2.[17]

D'Aubarede said Sharp disagreed with him that it was wrong to climb alone and to attempt summiting without using supplementary oxygen.[8] This is confirmed by Sharp's emails to other climbers in which he stated he did not believe in using extra oxygen.[8] He joined four climbers on this expedition, so Sharp relented on that point of disagreement, but only for a time, as he would return in 2006 for his solo attempt.[8] As a result of his 2004 attempt, Sharp incurred frostbite on his fingers during the expedition.

2006 Mount Everest expedition

Two years later, Sharp returned to Everest to reach the summit on a solo climb arranged through Asian Trekking. The attempt ultimately cost him his life.[13] Sharp was climbing alone and had intended to reach the summit without using supplementary oxygen, which is considered to be extremely risky even for very strong acclimatized mountain climbers or Sherpas.[5][18] However, Sharp apparently did not consider it a challenge to climb Everest with supplementary oxygen.[11] Sharp was climbing with a bare-bones "basic services" package from Asian Trekking that does not offer support after a certain altitude is reached on the mountain or a Sherpa to climb with as a partner, although this option was available to Sharp for an additional fee.[9] He was grouped with 13 other independent climbers – including Vitor Negrete, Thomas Weber, and Igor Plyushkin who also died attempting to summit that year – on the International Everest Expedition.[9] This package only provided a permit, a trip into Tibet, oxygen equipment, transportation, food, and tents up to the Mount Everest "Advance Base Camp" (ABC) at an elevation of about 6,340 m (20,800 ft).[9] The group Sharp was with was not really an "expedition" and had no leader, although it is considered good climbing ethics that members of the group make some effort to keep track of each other.[19]

Before Sharp booked his trip with Asian Trekking, his friend McGuinness, an experienced climber and guide, invited him to join his organized expedition at a discount. Sharp acknowledged this as a good deal but declined so he could act independently and climb at his own pace.[11] Critically, Sharp opted to climb alone without a climbing Sherpa, without sufficient supplementary oxygen (reportedly only two bottles, which is only enough for about 8 to 10 hours of climbing at high altitude) and without even a radio to call for help if he did encounter problems.[5][11][20][21][22]

Sharp was transported by vehicle to the Base Camp, and his equipment was transported by yak train to the Advance Base Camp, as part of the Asian Trekking "basic services" package. Sharp remained there for five days to acclimatize to the altitude.[9] He made several trips up and down the mountain to set up and stock his upper camps and further acclimatize himself. Sharp likely set out from a camp high on the mountain below the northeast ridge to make a summit attempt during the late evening of 13 May, and reportedly only had a very limited supply of supplementary oxygen he intended to use only in an emergency. Sharp either reached the summit or turned back near the summit to descend very late in the day on 14 May. He was forced to camp out exposed, or "bivouac", during his descent in the dark at about 8,500 m (28,000 ft) under a rock overhang known as Green Boots' Cave. There he was overcome by the elements without any remaining supplementary oxygen, possibly combined with equipment problems, on one of the coldest nights of the season.

Sharp's predicament was not immediately known for several reasons: he was not climbing with an expedition that would monitor climbers' locations; he had not told anyone beforehand of his summit attempt (although other climbers spotted him on his ascent); he did not have a radio or satellite phone with him to let anyone know where he was or that he was in trouble; and two other more inexperienced climbers from his group went missing at around the same time.[6] One of the two missing climbers was Malaysian Ravi Chandran, who was eventually found but required medical attention after getting frostbite.[23]

Some members of the group of climbers Sharp was with, including George Dijmarescu, realised Sharp was missing when he did not return later in the evening on 15 May and nobody reported seeing him. Sharp was an experienced climber who had previously turned around when he had experienced problems, and it was surmised that Sharp had sought shelter at one of the higher camps or bivouacked somewhere higher up on Everest, so his failure to return to camp did not initially cause serious concern.[24] High-altitude bivouacs are very risky but are sometimes recommended in certain extreme situations.[25]

Sharp may have bivouacked or rested at Green Boots' Cave due to the extreme cold and exhaustion, combined with problems with his equipment and no supplementary oxygen. He was likely also suffering some degree of altitude sickness due to a lack of supplementary oxygen. He was never able to get up and continue his descent, even with the help of other climbers and supplementary oxygen later in the morning on 15 May, and he subsequently died in Green Boots' Cave.

2006 Everest incident

Accounts of fatal climb

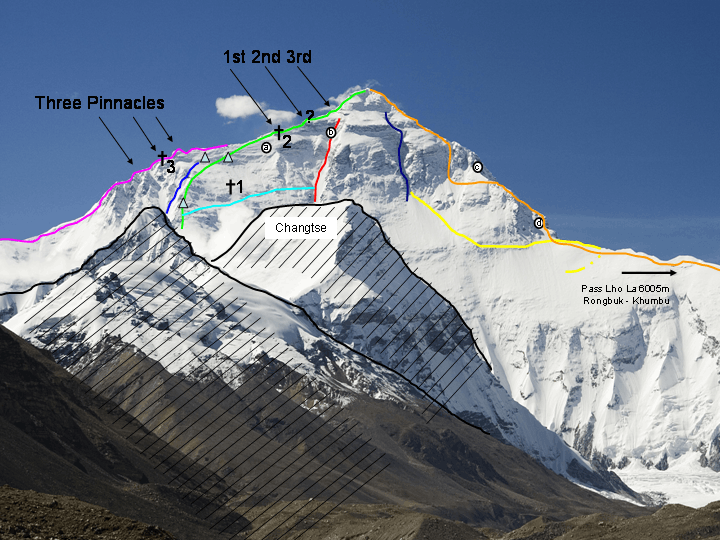

It is believed that Sharp set out during the evening of 13 May.[11] His high camp was just below the Northeast Ridge. He needed to climb what is referred to as the "Exit Cracks"; traverse the Northeast Ridge, including the Three Steps; reach the summit; then climb down to return to his high camp.[11]

American climber and Himex guide Bill Crouse and his group encountered someone, later believed to be Sharp, at the base of the Third Step in the afternoon on 14 May as they descended from the summit. During their descent, they saw him higher on the mountain.[6][9][26] Other climbers had also observed a lone climber, later believed to be Sharp, beginning his ascent along the northeast ridge on the way up to the summit late in the day. Back at base camp, other climbers who knew Sharp felt he was experienced enough to turn back if he became fatigued or had a problem.[6]

Sharp likely either reached the summit very late in the day and descended, or he turned back near the summit. Due to how late in the day Sharp was descending, along with other potential problems, such as issues with his equipment, potential exhaustion, and running out of oxygen,[27] Sharp apparently had to seek shelter. The extreme cold, fatigue, lack of oxygen and darkness likely made a descent to the high camp very dangerous or impossible.

Sharp ultimately died under a rock overhang below the summit along the Northeast Ridge known by climbers as "Green Boots' Cave" near the First Step at 8,500 m (28,000 ft) along the northeast ridge approach to the summit, sitting with arms clasped around his legs, next to and to the right of a green-booted body.[28] The overhang or "cave" at about 8,500 m (28,000 ft) is located alongside the main northeast climbing trail approximately 350 m (1,150 ft) below the summit and approximately 250 m (820 ft) above the high camps, commonly called Camp 4 above ABC. The high camps are located below the "Exit Cracks" that are just before the beginning of the Northeast Ridge route up to the summit.

The first climbers to encounter Sharp in the early morning on 15 May were making their summit push for later that day.[6] Most of them either did not notice Sharp in the dark, thought he was another corpse encountered climbing Everest, or thought he was beyond help. After climbers on the northern Tibetan side of Everest passed the rock overhang or "cave" in which Sharp lay incapacitated and later that day during their descents, they returned with a series of accounts and events that resulted in international media attention focused on Sharp's death and the climbers who saw him there.[6]

Himex Expedition – first team

Himex organized several teams to climb Everest during the 2006 climbing season expedition. The first team was guided by mountain climber and guide Bill Crouse. At about 01:00 on 14 May, Crouse's expedition team passed by Sharp during their own ascent.[9] They passed at a location on the common North route by a spot known as the "Exit Cracks".[9] When Crouse's team descended, they saw Sharp again at the base of the Third Step around 11:00.[9] By the time Crouse's expedition had descended to the Second Step, more than one hour later, they looked back to see that Sharp was above the Third Step, but was climbing very slowly and had only moved about 90 m (295 ft).[9]

Turkish team

Another source of reports about Sharp was a team of Turkish climbers.[27] They left their high camp in the evening on 14 May and were essentially traveling in three separate groups. Late in the evening to early morning, the Turkish team members encountered Sharp in the dark while ascending. The first group encountered Sharp around midnight, noticed he was alive, and thought that he appeared to be a climber taking a short break. Sharp waved them on. Some time later, others who noticed Sharp thought he was already dead; recovery of a dead climber's body is almost impossible due to the conditions.[19][28] It is thought Sharp fell asleep between these two times.[19] The fact that Sharp wanted to sleep was noted by other climbers who encountered him later on, and a quote telling people that he wanted to sleep was reported in some news media stories.[29]

Some of the Turkish team summited early in the morning on 15 May, and some turned back near the summit due to difficulties one of the team members was having.[27][30] The Turkish team members who turned back encountered Sharp again at about 7:00 am. One of them was the Turkish team leader, Serhan Pocan, who had previously passed Sharp in the night and thought Sharp was a climber who had recently died. In the daylight, Pocan realized that Sharp was alive and in serious trouble.[27]

Sharp had no oxygen left, had serious frostbite, and some limbs were frozen. Two of the Turkish climbers stayed, gave him something to drink, and tried to help him move. When they ran low on oxygen, they left with the intent to return with more oxygen. The Turks' initial effort to help was complicated by their own problems trying to get Burçak Özoğlu Poçan down safely; she was a climber in their group having medical problems.[27] Serhan Pocan placed radio calls to the rest of the team coming down from the summit about Sharp and continued descending with Burçak. At about 8:30 am, two other members of the Turkish team cleaned out Sharp's iced up mask to give him oxygen, but they started to run out of oxygen themselves and had to descend. The remaining Turks later attempted to further help Sharp along with other Himex expedition members.[27]

Himex Expedition – second team

The vanguard of the second team of Himex climbers included Max Chaya, New Zealand double-amputee Mark Inglis, Wayne Alexander (who designed Inglis' prosthetic climbing legs), Discovery cameraman Mark Whetu, experienced climbing guide Mark Woodward, and their Sherpas, including Phurba Tashi. The team left their high camp around 8,200 m (26,903 ft) late in the evening near midnight on 14 May. Chaya and the Sherpa he was climbing with were out in front by about a half hour.[31]

At about 1:00 am, Woodward and his group (including Inglis, Alexander, Whetu and some Sherpas) encountered Sharp, who Woodward knew should not be there. He was not conscious or moving, and had severe frostbite, but they could see that he was breathing. Woodward noticed Sharp had thin gloves and no oxygen, and indicated that they yelled at Sharp to get up, get moving and follow the headlamps back to the high camps. Woodward shined a headlamp in Sharp's eyes, but Sharp was unresponsive.[31]

Woodward thought he was almost dead and in a hypothermic coma, commenting, "Oh, this poor guy, he's stuffed", and believed Sharp could not be rescued. Woodward attempted to radio their advanced base camp about Sharp but got no reply.[11][20] Alexander commented, "God bless... Rest in peace", before the group moved on.[31] Woodward said it was not an easy decision to make, but his chief responsibility was the safety of his team members; stopping in the extreme cold at that time would have risked the lives of his team. At that elevation, one has to be conscious and able to walk to attempt a rescue.[5][31]

Maxime Chaya reached the summit at around 6:00 am.[30] During his descent, Chaya and the Sherpa he was with, Dorjee, encountered Sharp a little after 9:00 am, noticed he was shivering, and tried to help him; he also notified the Himex expedition manager Russell Brice over the group's radio.[20] Chaya had not seen Sharp in the darkness of the ascent. Chaya observed that Sharp was unconscious, shivering severely, and was wearing a thin pair of wool gloves with no hat, glasses or goggles. Sharp was severely frostbitten, had frozen hands and legs, and was found with only one empty oxygen bottle.[20]

At one point Sharp stopped shivering, leading Chaya to believe he had died; some time later he started shivering again. They attempted to give him oxygen, but there was no response. After about an hour, Brice advised Chaya that he was running out of oxygen and there was nothing he could do, so he needed to come down.[20] Chaya told The Washington Post: "it almost looks like he [David Sharp] had a death wish".[20]

Soon after Chaya descended, some of the others from the second Himex group and a Turkish group encountered Sharp again during their descent and attempted to help him.[5][20] Phurba Tashi, the lead Sherpa for Himex, and a Turkish Sherpa gave Sharp oxygen from a spare bottle they found, patted him to try to get circulation going and tried to give him something to drink. At one point Sharp mumbled a few sentences. The group tried to get Sharp to his feet, but he was not able to stand, even with assistance. They moved Sharp into the sunlight and descended.[20][31] It took the two strongest Sherpas about 20 minutes just to move Sharp about four steps into the sunlight, so they could not have taken Sharp with them.[5]

Mark Inglis controversy

Following David Sharp's death, Mark Inglis was initially severely criticized by the media and others, including Sir Edmund Hillary, for not helping Sharp.[5] Inglis stated that Sharp had been passed by 30 to 40 other climbers heading for the summit who made no attempt at a rescue, but he was criticized for not helping Sharp simply because he was more well known, even though he was a double amputee and was probably the least likely person to have been able to help anyone. Inglis said he believed that Sharp was ill-prepared, lacking proper gloves and oxygen, and was already doomed by the time of his ascent. He also initially stated, "I... radioed, and Russ [expedition manager Russell Brice] said, 'Mate, you can't do anything. He's been there x number of hours without oxygen. He's effectively dead.' Trouble is, at 8500 meters it's extremely difficult to keep yourself alive, let alone keep anyone else alive".[32]

Statements by Inglis suggest that he believed that Sharp was probably so close to death as to have been beyond help by the time the Inglis party passed him during his group's ascent and the reported radio calls to their base camp.[33] However Brice, who was initially criticized for reportedly advising Inglis during his ascent to move on without assessing the situation at that time or the possibility of rescue for Sharp, denies the claim that any radio call was received about the stranded climber until he was notified some eight hours later by the Lebanese climber Maxime Chaya, who had not seen Sharp in the darkness of the ascent.[5] At this time Sharp was unconscious and shivering violently with severe frostbite, and had no gloves or oxygen.[20] It was revealed that Brice kept detailed logs of radio calls with his expedition members, recorded all radio traffic, and that the Discovery channel was filming Brice during this time, all of which confirmed that Brice was first notified of Sharp being in trouble when climber Maxime Chaya contacted Brice at about 9:00 am.[5]

In the documentary Dying for Everest, Mark Inglis stated: "From my memory, I used the radio. I got a reply to move on and there is nothing that I can do to help. Now I'm not sure whether it was from Russell [Brice] or from someone else, or whether you know... it's just hypoxia and it's ... it's in your mind."[5] It is believed that if Inglis did in fact have a radio conversation where he was told that "he's been there x number of hours without oxygen" that it must have been on Inglis' descent, as there was no way for Brice or other climbers to have known how long Sharp had been where he was found during the climber's ascent, and in July 2006 Inglis retracted his claim that he was told to continue his ascent after informing Brice of a climber in distress, blaming the extreme conditions at altitude for the uncertainty in his memory.[34][35]

The Discovery Channel was filming the Himex expedition for a documentary Everest: Beyond the Limit, including an HD camera carried by Whetu (that became unusable during the ascent due to the extreme cold) and helmet cameras for some of the Himex Sherpas, which included footage indicating that Sharp was only found by Inglis's group on their descent. However, the group of climbers with Inglis confirmed that they did discover Sharp on the ascent, but they do not confirm that Brice was contacted regarding Sharp during the ascent. By the time the Inglis group reached him on the descent and contacted Brice they were low on oxygen and heavily fatigued, with several cases of severe frostbite and other problems on the mountain, making any rescue by them impossible.

Jamie McGuinness

New Zealand mountaineer Jamie McGuinness reported about a Sherpa that reached Sharp on the descent, "... Dawa from Arun Treks also gave oxygen to David and tried to help him move, repeatedly, for perhaps an hour. But he could not get David to stand alone or even stand resting on his shoulders ... Dawa had to leave him too. Even with two Sherpas it was not going to be possible to get David down the tricky sections below"[29]

McGuinness was part of an expedition that successfully climbed Cho Oyu with Sharp in 2002.[10] He also was on the 2003 expedition to Mount Everest with Sharp and other climbers,[13] and in 2006 offered Sharp the opportunity to climb Everest with his organized expedition for little more than what he ultimately paid Asian Trekking, which Sharp declined as he wanted to climb Everest independently.[11] In the documentary Dying For Everest, McGuiness noted that Sharp did not expect to be rescued ... "absolutely not, he was clear to me that he understood the risks and he did not want to endanger anyone else".[5]

Discovery Channel TV series

David Sharp was briefly caught on a camera in the morning on 15 May during filming of the first season of a television show Everest: Beyond the Limit, which was filmed the same season as his ill-fated expedition.[7] The footage was from the helmet camera of a Himex Sherpa who encountered Sharp, along with one of the Himex group of climbers who included Mark Inglis, during their descent, and was attempting to help Sharp along with a Turkish Sherpa.

Reactions

Sir Edmund Hillary

Sir Edmund Hillary was highly critical of the decision not to try to rescue Sharp, as reported by the media at that time, saying that leaving other climbers to die is unacceptable, and the desire to get to the summit has become all-important. He also said, "I think the whole attitude towards climbing Mount Everest has become rather horrifying. The people just want to get to the top. It was wrong if there was a man suffering altitude problems and was huddled under a rock, just to lift your hat, say good morning and pass on by". He told the New Zealand Herald that he was horrified by the callous attitude of today's climbers. "They don't give a damn for anybody else who may be in distress and it doesn't impress me at all that they leave someone lying under a rock to die", and that, "I think that their priority was to get to the top and the welfare of one of the ... of a member of another expedition was very secondary."[32] Hillary also called Mark Inglis "crazy".[5]

Sharp's mother

Linda Sharp, David's mother does not blame other climbers. She told The Sunday Times, "Your responsibility is to save yourself – not to try to save anybody else."[36]

David Watson

Mountaineer David Watson, who was on Everest that season on the North side, commented to The Washington Post: "It's too bad that none of the people who cared about David knew he was in trouble", because "the outcome would have been a lot different."[20] Watson thought it was possible to save Sharp, and he said Sharp had worked with other climbers in 2004, to save a Mexican climber who had gotten into trouble.[20] Watson was alerted the morning of 16 May by Phurba Tashi.[37] Watson went to Sharp's tent and showed Sharp's passport to Tashi, who confirmed his identity.[37] Around this time, a Korean team gave a radio report that the climber in red boots [Sharp] was dead.[37] He had his rucksack with him, but his camera was missing, so it is not known if he summited.[37]

References

- "'On Everest, you are never on your own'. Words of the climber left to". independent.co.uk. 25 May 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Breed, Allen G.; Gurubacharya, Binaj (16 July 2006). "Everest remains deadly draw for climbers". USA Today.

- "Everest remains deadly draw for climbers – USA TODAY". 16 July 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "The seven most riveting reads about Mount Everest". usatoday.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Dying For Everest". 2007 Documentary "Dying For Everest", New Zealand TV3 (21 August 2007), YouTube Video "Mt. Everest: David Sharp".

- "Everest remains deadly draw for climbers - USATODAY.com". usatoday.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Everest: Beyond the Limit". Competitor Magazine Online. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- http://www.peterleni.com/David%20Sharp%20Sunday%20Times%20Magazine.pdf

- Breed, Allen G.; Gurubacharya, Binaj (23 July 2006). "A Climber's Highest Ambition". Retrieved 1 October 2016 – via washingtonpost.com.

- "Cho Oyu 2002 Expeditions and News". everestnews.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "The Sunday Times – Left to die at the top of the world" (PDF).

- Carlson, Caitlin. "What it's Actually Like to Climb Everest With No Oxygen—and Document the Whole Thing on Snapchat". mensfitness.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Mount Everest Expeditions 2000 to 2009". everest1953.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Bowley, Graham (12 November 2010). "K2 tragedy: 'We had no body, no funeral, no farewell ...'". Retrieved 1 October 2016 – via The Guardian.

- "Himalayan Database Expedition Archives of Elizabeth Hawley". himalayandatabase.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "158 Summit Everest from Nepal in 2004: South Side Summits". everestnews2004.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Everest K2 News ExplorersWeb – ExplorersWeb Week in Review". explorersweb.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Master of Thin Air: Life and Death on the World's Highest Peaks". by Andrew Lock and Peter Hillary, 2015.

- "Everest K2 News ExplorersWeb – Turkish climbers about David Sharp: "He was not part of a team"". explorersweb.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- On Top of the World, But Abandoned There, The Washington Post, 30. Juli 2006

- "Everest climber left to die alone". The Washingtion Times. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- "Over the Top". Outside Online. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- "Everest 2006: Eight dead on Everest". everestnews.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Nation & World – Near the summit, David Sharp waved off fellow climbers: "I just want to sleep" – Seattle Times Newspaper". nwsource.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Lock, Andrew (1 September 2015). "Master of Thin Air: Life and Death on the World's Highest Peaks". Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. Retrieved 1 October 2016 – via Google Books.

- Everest: Beyond the Limit, season 1, episode 3

- "Everest 2006: The investigation into the death of David Sharp: The Turkish Expedition speaks in detail". everestnews.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "The Mount Everest Graveyard". MentalFloss Article by Stacy Conradt.

- Herald, New Zealand. "'Let me sleep' plea by dying climber". nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Himalayan Database Expedition Archives of Elizabeth Hawley". himalayandatabase.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Nick Heil (August 2006). "Left to Die on Everest". Men's Journal.

- McKinlay, Tom (24 May 2006). "Wrong to let climber die, says Sir Edmund". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Cheng, Derek (25 May 2006). "Dying Everest climber was frozen solid, says Inglis". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Amputee Lauded, Criticized for Everest Climb". npr.org. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Mount Everest Climbing Ethics | Outside Online". Archived from the original on 18 October 2006.

- Webster, Ben. "Focus: Has the once heroic sport of climbing been corrupted by big money? – Times Online". The Times. London.

- "Did Everest Climber Sharp Have to Die?". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Rachel Nuwer (9 October 2015). "Death in the Clouds: The problem with Everest's 200+ bodies". BBC Future. BBC. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

Further reading

- Dr. Morandeira: "Could David Sharp have been saved? Definitely", includes a chronology of the incident – mounteverest.net

- Everest 2006: "My name is David Sharp and I am with Asian Trekking" – everestnews.com