Dar al-Makhzen (Fez)

Dar al-Makhzen (Arabic: دار المخزن "House of the Makhzen") or Palais Royal (Arabic: القصر الملكي), is the royal palace of the King of Morocco in the city of Fes, Morocco. (Note: the term Dar al-Makhzen is used to refer to royal palaces throughout Morocco.)

.jpg)

Historical overview and layout

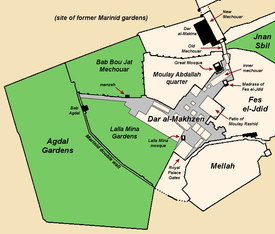

The palace is located in Fes el-Jdid ("New Fes"), the fortified royal district founded by the Marinid sultans in 1276.[1] Today it covers 80 hectares, taking up much of the city's area.[2]:310 Inside, the vast palace grounds are taken up by numerous courtyards, residential pavilions, gardens, and fountains.[3][2]

Marinid foundation and embellishment (late 13th century and after)

The palace was founded and initially built, along with the rest of Fes el-Jdid, by the Marinid sultan Abu Yusuf Ya'qub in 1276. It served as the new royal residence and center of government for Morocco under Marinid rule. Before this, the main center of power and government in Fes had been the Kasbah Bou Jeloud on the western edge of the old city (at the location of the still extant Bou Jeloud Mosque).[1] The decision to create a new and highly fortified citadel separate from the old city (Fes el-Bali) may have reflected a continuous wariness of Moroccan rulers towards the highly independent and sometimes restive population of Fes.[1] The Grand Mosque of Fes el-Jdid, adjacent to the palace grounds, was also founded at the same time as the new city in 1276 and was connected by a private passage directly to the palace, allowing the sultan to come and go for prayers.[4] What is now the Old Mechouar (a large walled courtyard preceding the main public entrance to the palace) was at that time a fortified bridge over the Oued Fes (Fes River) at the northern entrance to the city, and was most likely not directly connected to the palace itself.[5] Although the original layout of the palace cannot be fully reconstructed due to centuries of subsequent expansion and modification, it was most likely concentrated further southwest within the current palace grounds.[5]

Abu Yusuf Ya'qub had also wished to create a vast pleasure garden, perhaps in emulation of those he might have admired in Granada (such as the Generalife); however, he died in 1286 before this could be accomplished.[2]:290 His son and successor, Abu Ya'qub Yusuf, carried out the work instead in 1287, creating the vast Mosara Garden to the north of Fes el-Jdid.[2] This garden was supplied with water from the Oued Fes via an aqueduct fed by an enormous noria (waterwheel) near Bab Dekkakin. Both the gardens and the noria fell into disuse after the Marinid period and eventually disappeared, leaving only traces.[5][2]

Alaouite revival and expansion (17th century and after)

Following years of neglect, the original Marinid constructions mostly fell into disrepair and were only restored, rebuilt, or replaced when the Alaouite sultans re-invested in Fes and made it the capital of Morocco again (with the exception of certain periods).[2] As a result, the current structures in the palace mainly date from the Alaouite period, from the 17th century and after.[3] In 1671, Sultan Moulay Rashid ordered the creation of a vast rectangular courtyard in the eastern part of the palace. The courtyard, still extant today, was adorned with green zellij tiles and centered around a large rectangular water basin.[2]:294 This addition extended the Dar al-Makhzen grounds up to the edge of the Lalla ez-Zhar Mosque, which had previously stood in the middle of a residential neighbourhood, and cutting off one of the local streets.[5] This was one of several occasions where the expansion of the palace cut into the general residential areas of Fes el-Jdid.[2] Moulay Rashid also built the vast Kasbah Cherarda north of Fes el-Jdid in order to house his tribal troops.[2][1] The housing of troops here also liberated new space in Fes el-Jdid itself, including the northwestern area which became the new Moulay Abdallah neighbourhood from the early 18th century onwards.[2]:296 This is where Sultan Moulay Abdallah (ruled between 1729 and 1757) erected a large mosque and royal necropolis for the Alaouite dynasty.[4] Abdallah's successor, Sultan Mohammed ben Abdallah (ruled 1748 and 1757-1790), was responsible, according to some sources[6], for establishing the New Mechouar (north of the Old Mechouar); though other scholars attribute this to Moulay Hassan a century later.[5][2]:296 Mohammed ben Abdallah also built a large and imposing palace structure called the Dar Ayad al-Kbira inside the palace grounds.[2]:310

Major expansions and modifications continued throughout the 19th century. Under sultan Moulay Abd al-Rahman (ruled 1822-1859) the Bab Bou Jat Mechouar or Grand Mechouar was created to the west of the Moulay Abdallah quarter, providing the palace grounds with another ceremonial entrance to the northwest.[1] Moulay Abd al-Rahman also expanded the gardens of the palace to the west, up to the old western Marinid walls of the city, by creating the Lalla Mina Gardens and building the adjoining Lalla Mina Mosque.[1] West of these, beyond the old walls, an even larger walled garden called the Agdal was established by Sultan Moulay Hassan I.[2][1] (According to some, the Lalla Mina Mosque is also attributed to Moulay Hassan.[7]:126) Moulay Hassan carried out many other significant works throughout Fes el-Jdid. Most notably, he connected Fes el-Jdid and Fes el-Bali (the old city) for the first time with a broad corridor of walls, and inside this space he commissioned a number of royal gardens (such as Jnan Sbil) and summer palaces (such as Dar Batha), separate but associated with the palace.[1][6] According to scholars it was also Moulay Hassan who built what is now known as the New Mechouar to the north of the old one.[5][2] All sources agree that he built the Dar al-Makina factory on the west side of the new square in 1886.[1][5][6]

Lastly, it seems to have been under Moulay Hassan that the Dar al-Makhzen grounds were extended northwards up to the south gate of the Old Mechouar, thus turning it into the main entrance of the palace instead of the main entrance of the city. This forced the diversion of the northern end of Fes el-Jdid's main street so that it now enters the Old Mechouar from the side.[5] The new expansion included a vast rectangular courtyard to serve as an "inner mechouar", followed by several other courtyards extending up to the Old Mechouar's gate.[5] This inner mechouar was lined by arcades and housed a number of public and administrative functions like the makhama (courthouse). This mechouar also lay between the Grand Mosque of Fes el-Jdid and its former madrasa (the Madrasa Fes el-Jdid), cutting them off from each other and resulting in the madrasa being integrated into the palace.[5]

Historically, members of the public and government officials could only access the first few courtyards of the Dar al-Makhzen (entered via the Old Mechouar) due to some public government institutions and tribunals being housed here.[1] The Old Mechouar, and adjacent courtyards, were thus a reception and waiting area for those who had business inside the palace.[1] The rest of the palace further west, however, made up the sultan's private residence and was not accessible to anyone but the sultan, his family, and his inner circle.[3]:95-96

Recent history (20th century) and present day

.jpg)

Although the capital of Morocco was moved to Rabat in 1912 and never returned to Fes, the palace complex in Fes is still frequently used by the King of Morocco.[2] The palace is thus not open to the public.[8] The gates at the Old Mechouar and at Place des Alaouites (see below) are the closest that most members of the public can get to the palace grounds.

The new Gates of the Royal Palace

In the 1960s King Hassan II reoriented the entrance of the palace complex from the Old Mechouar in the north to a new southern approach facing the modern Ville Nouvelle of Fes. A new grand square, Place des Alaouites, was laid out and new ornate gates to the palace were built between 1969 and 1971.[6] The gates are considered an excellent piece of modern Moroccan crafstmanship and are lavishly decorated with elaborate mosaic tilework, carved cedar wood, and doors of gilt bronze covered in geometric patterns.[8]

The mechouars

.jpg)

In the context of palace architecture, the term "mechouar" (from the French transliteration, méchouar, of Arabic المشور; sometimes spelled mishwar or meshwar in English) generally refers to an official square or courtyard at the entrance of the royal palace. Such squares were used for various open-air ceremonies, the reception of ambassadors, and as waiting areas for those entering the palace.[1] They were often also part of the setting for the dispensation of justice or the receiving of petitions to the ruler. For example, the main qadi (judge) of Fes Jdid held his tribunal near the entrance of the palace, located just inside the entrance from the Old Mechouar.[1]:95, 266 There are at least three historical mechouars attached the royal palace of Fes.

Old Mechouar (Vieux Méchouar)

The smallest of the mechouars of Fes, this courtyard immediately precedes the official entrance to the Dar al-Makhzen. The mechouar is enclosed by ramparts on all sides and dates to the Marinid period.[6] It appears that it was originally a fortified bridge over the Oued Fes (Fez River), with fortified gates at either end.[5] The river still passes underneath the square, reemerging via four semi-circular openings at the eastern base of its walls on the edge of the Jnan Sbil Gardens.[1]

On the southern side of the square today is the gate to the Dar al-Makhzen; until the creation of the new palace gates in the southwest, this was the main entrance to the palace.[6]:148 However, this was originally occupied by a gate called Bab al-Qantara ("Gate of the Bridge") or Bab el-Oued ("Gate of the River") which had been the northern entrance to the whole city before the palace grounds were expanded and it became the gate to the Dar al-Makhzen itself.[1]:62 On the square's northern side is Bab Dekkakin (originally called Bab es-Sebaa), the monumental gate leading to and from the New Mechouar (see below). To the west, an opening in the walls leads to the Moulay Abdallah residential district of Fes el-Jdid. On the square's east side are two other openings in the wall. The southern one leads to the Grande Rue (main street) of Fes el-Jdid (which leads to Bab Semmarine and the Jewish Mellah beyond), while the northern opening gives access to the road leading towards Place Bou Jeloud and the entrance to Fes el Bali. Because of this crossroads, the mechouar is one of the busiest squares in Fes el-Jdid today.[6]

New Mechouar (Nouveau Méchouar)

To the north of the Old Mechouar, through the monumental Bab Dekkakin ("Gate of the Benches"; also known as Bab es-Sebaa, "Gate of the Lion"), lies the larger New Mechouar. According to some, this was laid out under the Alaouite Sultan Moulay Muhammad ibn Abdallah (Mohammed III) during his reign (1757-1790).[6] According to other scholars, however, it was the work of Sultan Moulay Hassan (Hassan I) a century later.[5]

On the western side of the square is a gateway in the Italianate architectural style which belongs to the Makina (Dar al-Makina), a former arms factory (also called Dar al-Silah) established by Moulay Hassan in 1886 with the help of Italian officers.[6][1] Originally, though, this western wall was actually a large Marinid aqueduct built in 1286 to carry water to the Mosara Garden in the north; the faint outline of its arches can still be seen today.[5] The northern gate of the New Mechouar, known as Bab Kbibat es-Smen ("Gate of the Butter Niche"), also dates from the 1886 construction, though another gate called Bab Segma also lends its name to the area.[6]

Bab Bou Jat Mechouar

Also known as the "Grand Mechouar", this vast irregular quadrilateral space of 4 hectares occupied the northwestern corner of Fes el Jdid in an angle between the walls of the palace grounds to the south and the Moulay Abdallah district to the east.[1]:97-98 The military square was laid out in the mid-19th century by Abd al-Rahman de Saulty, a Muslim convert and officer in the military engineers corps under Sultan Moulay Abd al-Rahman (ruled 1822-1859).[1]:90, 181 The creation of the mechouar required a minor diversion of the Oued Fes river at the time.[1] Bab Bou Jat, the main western gate of the Moulday Abdallah quarter, once opened through here but was closed off in the 20th century.[1] On the south side of the square is a menzeh, an elevated pavilion from which the sultan could observe ceremonies taking place in the square, which was built by Sultan Abdelaziz (ruled 1894-1908).[1]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dar al-Makhzen (Fes). |

- Le Tourneau, Roger (1949). Fès avant le protectorat : étude économique et sociale d'une ville de l'occident musulman. Casablanca: Société Marocaine de Librairie et d'Édition.

- Métalsi, Mohamed (2003). Fès: La ville essentielle. Paris: ACR Édition Internationale. ISBN 978-2867701528.

- Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- Maslow, Boris (1937). Les mosquées de Fès et du nord du Maroc. Paris: Éditions d'art et d'histoire.

- Bressolette, Henri; Delaroziere, Jean (1983). "Fès-Jdid de sa fondation en 1276 au milieu du XXe siècle". Hespéris-Tamuda: 245–318.

- Parker, Richard (1981). A practical guide to Islamic Monuments in Morocco. Charlottesville, VA: The Baraka Press.

- Le Tourneau, Roger (1949). Fès avant le protectorat: étude économique et sociale d'une ville de l'occident musulman. Casablanca: Société Marocaine de Librairie et d'Édition.

- Royal Palace. Lonely Planet. Retrieved January 24, 2018.