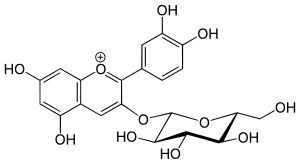

Chrysanthemin

Chrysanthemin is an anthocyanin. It is the 3-glucoside of cyanidin.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-2-[2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxychromenylium-3-yl]oxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane-3,4,5-triol chloride | |

| Other names

Chrysontenin Glucocyanidin Asterin Chrysanthemin Purple corn color Kuromanin Kuromanin chloride Cyanidin 3-glucoside Cyanidol 3-glucoside Cyanidine 3-glucoside Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside cyanidin-3-O-beta-D-glucoside Cyanidin 3-monoglucoside C3G | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.027.622 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C21H21O11+, Cl− C21H21ClO11 | |

| Molar mass | 484.83 g/mol (chloride) 449.38 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Natural occurrences

Chrysanthemin can be found in the roselle plant (Hibiscus sabdariffa, Malvaceae), different Japanese angiosperms,[1] Rhaponticum (Asteraceae),[2] The fruits of the smooth arrowwood (Viburnum dentatum, Caprifoliaceae) appear blue. One of the major pigments is cyanidin 3-glucoside, but the total mixture is very complex.[3]

In food

Chrysanthemin has been detected in blackcurrant pomace, in European elderberry,[4] in red raspberries, in soybean seed coats,[5] in victoria plum,[6] in peach,[7] lychee and açaí.[8] It is found in red oranges[9] and black rice.[10]

It is the major anthocyanin in purple corn (Zea mays). Purple corn is approved in Japan and listed in the "Existing Food Additive List" as purple corn color.[11]

Biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of cyanidin 3-O-glucoside in Escherichia coli was demonstrated by means of genetic engineering.[12]

In Arabidopsis thaliana, a glycosyltransferase, UGT79B1, is involved in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway. UGT79B1 protein converts cyanidin 3-O-glucoside to cyanidin 3-O-xylosyl(1→2)glucoside.[13]

References

- Yoshitama, Kunijiro (1972). "A survey of anthocyanins in sprouting leaves of some Japanese angiosperms studies on anthocyanins, LXV". The Botanical Magazine Tokyo. 85: 303–306. doi:10.1007/BF02490176.

- Vereskovskii, V. V. (1978). "Chrysanthemin and cyanin in species of the genusRhaponticum". Chemistry of Natural Compounds. 14: 450–451. doi:10.1007/BF00565267.

- Francis, F.J. (1989). "Food colorants: Anthocyanins". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 28: 273–314. doi:10.1080/10408398909527503. PMID 2690857.

- Foods in which the polyphenol Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside is found, http://www.phenol-explorer.eu/contents/polyphenol/9

- Choung, Myoung-Gun; Baek, In-Youl; Kang, Sung-Taeg; Han, Won-Young; Doo-Chull, Shin; Moon, Huhn-Pal; Kang, Kwang-Hee (2001). "Isolation and Determination of Anthocyanins in Seed Coats of Black Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 49 (12): 5848–5851. doi:10.1021/jf010550w. PMID 11743773.

- Dickinson, D. (1956). "The chemical constituents of victoria plums: Chrysanthemin, acid and pectin contents". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 7: 699–705. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740071103.

- Postharvest sensory and phenolic characterization of 'Elegant Lady and 'Carson' peaches. Rodrigo Infante, Loreto Contador, Pía Rubio, Danilo Aros and Álvaro Peña-Neira, Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research, 71(3), July–September 2011, pages 445–451 (article)

- Del Pozo-Insfran D, Brenes CH, Talcott ST (March 2004). "Phytochemical composition and pigment stability of Açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.)". J. Agric. Food Chem. 52 (6): 1539–45. doi:10.1021/jf035189n. PMID 15030208.

- Felgines, C; Texier, O; Besson, C; Vitaglione, P; Lamaison, JL; Fogliano, V; Scalbert, A; Vanella, L; Galvano, F (2008). "Influence of glucose on cyanidin 3-glucoside absorption in rats". Mol Nutr Food Res. 52: 959–64. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200700377. PMID 18646002.

- Um, Min Young; Ahn, Jiyun; Ha, Tae Youl (2013-09-01). "Hypolipidaemic effects of cyanidin 3-glucoside rich extract from black rice through regulating hepatic lipogenic enzyme activities". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 93 (12): 3126–3128. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6070. ISSN 1097-0010. PMID 23471845.

- Anthocyanins isolated from purple corn (Zea mays L.). Hiromitsu Aoki, Noriko Kuze and Yoshiaki Kato (article Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine)

- Yan Y, Chemler J, Huang L, Martens S, Koffas MA (2005). "Metabolic engineering of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Escherichia coli". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 (7): 3617–23. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.7.3617-3623.2005. PMC 1169036. PMID 16000769.

- Yonekura-Sakakibara, Keiko; Fukushima, Atsushi; Nakabayashi, Ryo; Hanada, Kousuke; Matsuda, Fumio; Sugawara, Satoko; Inoue, Eri; Kuromori, Takashi; Ito, Takuya; Shinozaki, Kazuo; Wangwattana, Bunyapa; Yamazaki, Mami (2012). "Two glycosyltransferases involved in anthocyanin modi?cation delineated by transcriptome independent component analysis in Arabidopsis thaliana". The Plant Journal. 69 (1): 154–167. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04779.x. PMC 3507004. PMID 21899608.