Crab claw sail

The crab claw sail or, as it is sometimes known, Oceanic lateen or Oceanic sprit, is a triangular sail with spars along upper and lower edges. The crab claw sail is used in many traditional Austronesian cultures, as can be seen by the traditional paraw, proa, lakana, and tepukei.

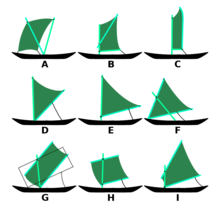

- Double sprit (Sri Lanka)

- Common sprit (Philippines)

- Oceanic sprit (Tahiti)

- Oceanic sprit (Marquesas)

- Oceanic sprit (Philippines)

- Crane sprit (Marshall Islands)

- Rectangular boom lug (Maluku Islands)

- Square boom lug (Gulf of Thailand)

- Trapezial boom lug (Vietnam)

History

Austronesians traditionally made their sails, including crab claw sails, from woven mats of the resilient and salt-resistant pandanus leaves. These sails allowed Austronesians to embark on long-distance voyaging. In some cases, however, they were one-way voyages. The failure of pandanus to establish populations in Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and Aotearoa (New Zealand) is believed to have isolated their settlements from the rest of Polynesia.[2][3]

There are competing theories on how the triangular sail shape arose. According to one theory, contact between Arabs and Austronesians in their Indian Ocean voyages may have influence the development of the triangular Arabic lateen sail and the development of the Austronesian rectangular tanja sail of western Southeast Asia.[4] Others attribute the invention of the tanja sail to the Nusantaran people, which then may have influenced the Arabs to develop their lateen sail and the Polynesians to develop crab claw sail.[5][6][7] A third theory suggests that Portuguese sailors introduced the lateen sail to Asian waters, starting with Vasco da Gama's arrival in India in 1500.[8]:257f

In Indonesia, crab claw sail appeared as a recent development. Traditionally the people from Nusantara archipelago use the tanja sail, but starting in the 19th century the Madurese people developed the lete sail. "Lete" actually means lateen, but the existence of pekaki (lower spar/boom) indicates that the layar lete is crab claw sail.[9]

Construction

The crab claw sail consists of a sail, approximately an isosceles triangle in shape. The equal length sides are usually longer than the third side, with spars along the long sides.

The crab claw may also traditionally be constructed with curved spars, giving the edges of the sail along the spars a convex shape, while the leech of the sail is often quite concave to keep it stiff on the trailing edge. These features give it its distinct, claw-like shape. Modern crab claws generally have straighter spars and a less convex leech, which gives more sail area for a given length of spar. Spars may taper towards the leech. The structure helps the sail to spill gusts.

The crab claw characteristically widens upwards, putting more sail area higher above the ocean, where the wind is stronger and steadier. This increases the heeling moment: the sails tend to blow the watercraft over. For this reason, crabclaws are typically used on multihulls, which resist heeling more strongly.

The sail is shunted; the bow becomes the stern, and the mast rake is also reversed. The vessel therefore always has the ama (and sidestay, if there is one) to windward, and has no bad tack

Proa: single mast with crab claw sail

Proa: single mast with crab claw sail Proa-like crabclaw

Proa-like crabclaw New Guinea-style crabclaw rig

New Guinea-style crabclaw rig Crabclaw amalgamating mast and 'ōpe'a

Crabclaw amalgamating mast and 'ōpe'a

Proa

In a proa, the forward intersection of the spars is placed towards the bow. The sail is supported by a short mast attached near the middle of the upper spar, and the forward corner is attached to the hull. The lower spar, or boom, is attached at the forward intersection, but is not attached to the mast. The proa has a permanent windward and leeward side, and exchanges one end for the other when coming about.

To tack, or switch directions across the wind, the forward corner of the sail is loosened and then transferred to the opposite end of the boat, a process called shunting.[10] To shunt, the proa's sheet is let out. The joined corner of the spars is then transferred to the opposite end of the boat. While remaining attached to the top of the mast, the upper spar tilts to vertical and beyond as the forward corner moves past the mast and onward to the other end of the boat. Meanwhile, the mainsheet is detached and used to rotate the rearward end of the boom through a horizontal half circle. The spar join is then re-attached at the new "forward" end of the boat and the mainsheet is re-tightened at the new "rearward" end.[11]

Tepukei

A shunting rig with the sail propped vertically at the bow, very similar to the proa rig described above.

Non-shunting crab claw

Hokule'a, a bluewater waʻa kaulua, with curved-spar, curved-leech crabclaw sails, in 1976.

Hokule'a, a bluewater waʻa kaulua, with curved-spar, curved-leech crabclaw sails, in 1976. Hokule'a in 2009, with simpler crab-claw sails.

Hokule'a in 2009, with simpler crab-claw sails. Hokule'a with her kaula pe'a (sail lines) tightened to partly close her crab-claw sails.[12]

Hokule'a with her kaula pe'a (sail lines) tightened to partly close her crab-claw sails.[12]

The term "crabclaw sail" is also used for non-shunting sails that widen upwards.[13] The 'ōpe'a, the upper spar, is braced up so high that it is nearly parallel to the mast (as in a gunter rig). The paepae, the lower spar/boom, points well above the horizontal, unlike the boom of most gunter rigs and gaff rigs. The two spars can be brought together or pulled apart with control lines.[14] The mast is fixed and stayed.[12]

Performance

The crab-claw sail is something of an enigma. It has been demonstrated to produce very large amounts of lift when reaching, and overall seems superior to any other simple sail plan (this discounts the use of specialised sails such as spinnakers). C. A. Marchaj, a researcher who has experimented extensively with both modern rigs for racing sailboats and traditional sailing rigs from around the world, has done wind tunnel testing of scale models of crab-claw rigs. One popular but disputed theory is that the crab-claw wing works like a delta wing, generating vortex lift. Since the crab claw does not lie symmetric to the airflow, like an aircraft delta wing, but rather lies with the lower spar nearly parallel to the water, the airflow is not symmetric. However, the presence of the water, close to the lower spar and parallel to it, makes the airflow behave roughly like the airflow over half of a delta wing, as though a "reflection" in the water provided the other half (apart from a narrow gap near the water, which causes a small difference there).

This can clearly be seen in Marchaj's wind tunnel photos published in Sail Performance: Techniques to Maximise Sail Power (1996). The vortex on the top spar of the sail is much larger, covering most of the sail area, while the lower vortex is very small and stays close to the spar. Marchaj attributes the large lifting power of the sail to lift generated by the vortices, while others attribute the power to a favourable mix of aspect ratio, camber and (lack of) twist at this point of sail.[15][16]

A more modern academic wind tunnel study (2014) provided similar results, with the Santa Cruz Islands tepukei's crab claw sail configuration dominating measurements.[17]

Gallery

Micronesian proa with crab claw sail

Micronesian proa with crab claw sail

.jpg) Postcard of a paraw sailboat from the Philippines (c.1940)

Postcard of a paraw sailboat from the Philippines (c.1940)- A proa in New Caledonia

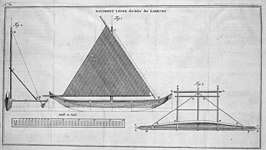

Illustration of a crab claw sail in Tikehau (Louis Choris, 1816)

Illustration of a crab claw sail in Tikehau (Louis Choris, 1816)

1750 illustration of crab claw sail by George Anson

1750 illustration of crab claw sail by George Anson

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crab claw sails. |

- Hokule'a

- Jangada

- Junk rig

- Outrigger canoe

- Proa

- Tanja sail

- Tepukei

Related rigs

- Gaff rig

- Gunter rig

- Lateen rig, modern crabclaw-like variants

References

- Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (2012). A Shark Going Inland Is My Chief: The Island Civilization of Ancient Hawai'i. University of California Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9780520953833.

- Gallaher, Timothy (2014). "The Past and Future of Hala (Pandanus tectorius) in Hawaii". In Keawe, Lia O'Neill M.A.; MacDowell, Marsha; Dewhurst, C. Kurt (eds.). ʻIke Ulana Lau Hala: The Vitality and Vibrancy of Lau Hala Weaving Traditions in Hawaiʻi. Hawai'inuiakea School of Hawaiian Knowledge ; University of Hawai'i Press. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.2571.4648. ISBN 9780824840938.

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts (PDF). One World Archaeology. 34. Routledge. p. 144-179. ISBN 0415100542.

- Shaffer, Lynda Norene (1996). Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500. M.E. Sharpe.

- Hourani, George Fadlo (1951). Arab Seafaring in the Indian Ocean in Ancient and Early Medieval Times. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Johnstone, Paul (1980). The Seacraft of Prehistory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674795952.

- White, Lynn (1978). Medieval Religion and Technology. Collected Essays. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03566-9.

- Horridge, Adrian (1981). The Prahu: Traditional Sailingboat of Indonesia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gross, Jeffrey L. (2016). Waipio Valley: A Polynesian Journey from Eden to Eden. Xlibris Corporation. p. 626. ISBN 9781479798469.

- Editor (July 23, 2014). "Proa Rig Options: Crab Claw". proafile.com. Proa File. Retrieved 2017-04-21.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Parts of the Hawaiian Canoe". archive.hokulea.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Star-Bulletin, Honolulu. "starbulletin.com - News - /2007/03/06/". archives.starbulletin.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Hōkūle‘a Image Gallery (From 1973) archive.hokulea.com, accessed 12 February 2020

- Marchaj, C. A. Sail Performance: Techniques to Maximise Sail Power. ISBN 0-07-141310-3.

- Slotboom, Bernard. "Delta Sail in A "Wind Tunnel" Experiences". Experiences from B.J. Slotboom. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- Anne Di Piazza, Erik Pearthree and Francois Paille (2014). "Wind Tunnel Measurements of the Performance of Canoe Sails from Oceania". Journal of the Polynesian Society.

.jpg)