Constituencies of Singapore

Constituencies in Singapore are electoral divisions which may be represented by single or multiple seats in the Parliament of Singapore. Constituencies are classified as either Single Member Constituencies (SMCs) or Group Representation Constituencies (GRCs). SMCs are single-seat constituencies but GRCs have between four and six seats in Parliament.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Singapore |

|

|

|

Related topics |

|

|

Group Representation Constituencies

Group Representation Constituencies (GRCs) are a type of electoral constituency unique to Singaporean politics. GRCs are multi-member constituencies which are contested by teams of candidates from one party - or from independents. In each GRC, at least one candidate or Member of Parliament must be from a minority race: either a Malay, Indian or Other.[1]

In 1988, the ruling People's Action Party (PAP) amended the Parliamentary Elections Act[2] to create GRCs. The current Act enables the President, acting on the advice of the Prime Minister, to create a GRC from three to six electoral wards. In creating GRCs the President is advised by the Elections Department. The initial maximum size for GRCs was three candidates, but this has subsequently been increased. In the 1991 Singaporean general election, the maximum number of candidates was raised from three to four. In 1997 the maximum number of candidates was further raised to six.[1]

GRCs operate with a plurality voting system, voting by party slate, meaning that the party with the largest share of votes wins all seats in the GRC. (This means that even with a one-vote plurality or majority, the winning team gets to win the whole GRC.) All Singaporean GRCs have had a PAP base.

The official justification for GRCs is to allow minority representation. Former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong argued that the introduction of GRCs was necessary to ensure that Singapore's Parliament would continue to be multiracial in its composition and representation.[3] Opposition parties have criticized GRCs as making it even more difficult for non-PAP candidates to be elected to Parliament. The money required to contest a GRC is considerable as each candidate is required to pay a S$16,000 deposit.[1] This means that contesting a GRC is very costly for opposition parties. The presence of Cabinet Ministers in GRCs is often believed to give the PAP a considerable advantage in the contesting of a GRC. The PAP has used this tactic to its advantage on several occasions. Rather than stand in an uncontested GRC, in 1997, then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong shifted his attention to campaigning for candidates where the PAP believed they were most vulnerable, which was the Cheng San GRC.[4] The opposition has charged the government with gerrymandering due to the changing of GRC boundaries at very short notice (see below section on electoral boundaries).

Critics have noted that Joshua Benjamin Jeyaratnam won the 1981 Anson by-election in a Chinese-majority constituency, and that since the GRC system was implemented, minority representation in Parliament has actually declined.

Boundaries and gerrymandering allegations

The boundaries of electoral constituencies in Singapore are decided by the Elections Department, which is under the control of the Prime Minister's Office.[5] Electoral boundaries are generally announced close to elections, usually a few days before the election itself is announced.[5][6] There have been accusations of gerrymandering regarding the redrawing of electoral boundaries and the dissolving of constituencies that return a high percentage of votes for parties other than the ruling PAP.[7]

One of the cases that is often cited as evidence for gerrymandering in Singapore is the case of the Cheng San Group Representation Constituency (GRC). In the 1997 Singaporean general election, the Cheng San GRC was contested by the PAP and the Workers' Party of Singapore (WP). The final results were close, with the PAP winning by 53,553 votes (54.8%) to the WP's 44,132 votes (45.2%). Cheng San GRC had since dissolved thereafter following the 2001 General Elections. Despite the disadvantages assumed by the opposition party in Singapore, the Workers' Party of Singapore would later be successful in taking over a GRC (Aljunied GRC) during the 2011 General Elections,[7] and would later hold on for another term in the subsequent election in 2015 despite winning a tight margin of less than 2%.

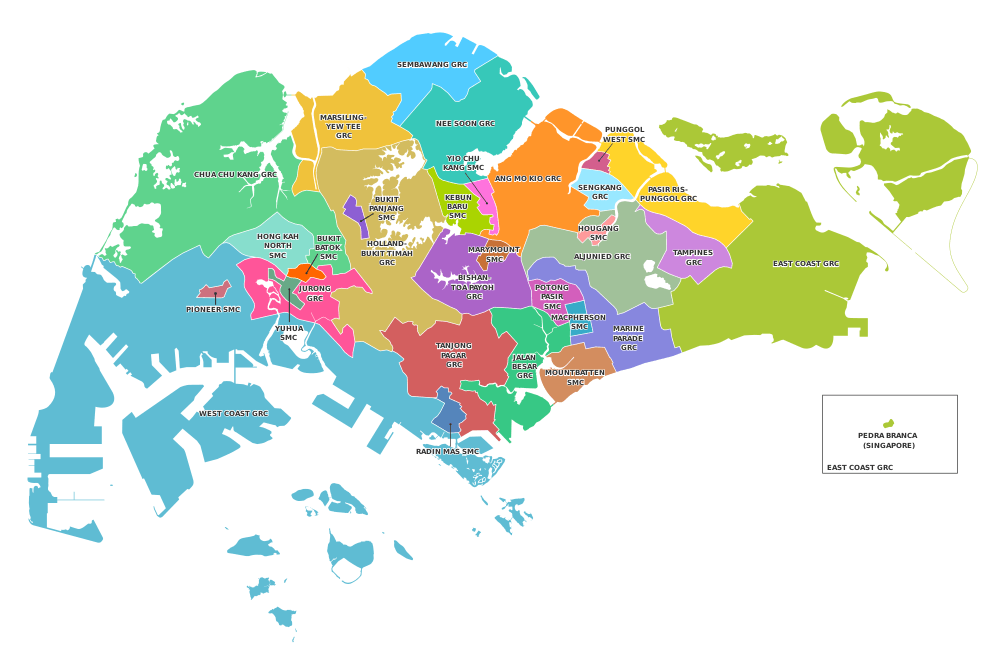

Current Electoral Map (2020–present)

As of the revision of the electorates on 15 April 2020, the number of electors in the latest Registers of Electors is 2,653,942.

Group Representation Constituencies

| Division | Seats | Electorate | Precincts[8] | Wards | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Present[9] | ||||

| Aljunied Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 150,303 | 51 | Bedok Reservoir-Punggol, Eunos, Kaki Bukit, Paya Lebar and Serangoon |

| Ang Mo Kio Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Indian/Other MP) | TBC | 180,186 | 59 | Ang Mo Kio-Hougang, Cheng San-Seletar, Jalan Kayu, Sengkang South and Teck Ghee |

| Bishan–Toa Payoh Group Representation Constituency | 4 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 100,036 | 34 | Bishan, Toa Payoh East, Toa Payoh West, Toa Payoh Central |

| Chua Chu Kang Group Representation Constituency | 4 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 103,231 | 34 | Bukit Gombak, Chua Chu Kang, Keat Hong |

| East Coast Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 120,239 | 41 | Bedok, Changi-Simei, Fengshan, Kampong Chai Chee and Siglap |

| Holland–Bukit Timah Group Representation Constituency | 4 (at least one Indian/Other MP) | TBC | 112,999 | 38 | Bukit Timah, Cashew, Ulu Pandan and Zhenghua |

| Jalan Besar Group Representation Constituency | 4 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 106,578 | 42 | Kampong Glam, Kolam Ayer, Kreta Ayer–Kim Seng and Whampoa |

| Jurong Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Indian/Other MP) | TBC | 129,933 | 45 | Bukit Batok East, Clementi, Jurong Central, Jurong Spring and Taman Jurong |

| Marine Parade Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 137,906 | 47 | Braddell Heights, Geylang Serai, Kembangan-Chai Chee, Marine Parade and Joo Chiat |

| Marsiling–Yew Tee Group Representation Constituency | 4 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 114,243 | 40 | Limbang, Marsiling, Woodgrove and Yew Tee |

| Nee Soon Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Indian/Other MP) | TBC | 137,906 | 45 | Chong Pang, Nee Soon South, Nee Soon South, Nee Soon East |

| Pasir Ris–Punggol Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 161,952 | 55 | Pasir Ris East, Pasir Ris West, Punggol North, Punggol Coast |

| Sembawang Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 139,724 | 47 | Admiralty, Canberra, Gambas, Sembawang and Woodlands |

| Sengkang Group Representation Constituency | 4 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 117,546 | 38 | TBC |

| Tampines Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Malay MP) | TBC | 147,249 | 51 | Tampines Central, Tampines Changkat, Tampines East, Tampines North and Tampines West |

| Tanjong Pagar Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Indian/Other MP) | TBC | 132,598 | 49 | Buona Vista, Henderson-Dawson, Moulmein-Cairnhill, Queenstown and Tanjong Pagar-Tiong Bahru |

| West Coast Group Representation Constituency | 5 (at least one Indian/Other MP) | TBC | 144,516 | 50 | Ayer Rajah, Boon Lay, Nanyang, Telok Blangah, West Coast |

Single Member Constituencies

| Division | Seats | Electorate | Precinct[8] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Present[9] | |||

| Bukit Batok Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 29,389 | 10 |

| Bukit Panjang Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 35,258 | 12 |

| Hong Kah North Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 23,519 | 8 |

| Hougang Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 25,629 | 9 |

| Kebun Baru Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 22,413 | 7 |

| MacPherson Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 27,652 | 10 |

| Marymount Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 23,439 | 7 |

| Mountbatten Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 23,957 | 8 |

| Pioneer Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 24,679 | 9 |

| Potong Pasir Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 18,551 | 6 |

| Punggol West Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 25,440 | 6 |

| Radin Mas Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 25,167 | 10 |

| Yio Chu Kang Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 26,046 | 9 |

| Yuhua Single Member Constituency | 1 | TBC | 21,188 | 8 |

See also

- Past Singaporean electoral divisions

- General elections in Singapore

References

- Hussin Mutalib, 'Constituational-Electoral Reforms and Politics in Singapore', Legislative Studies Quarterly 21 (2) (2002), p. 665.

- Now the Parliamentary Elections Act (Cap. 218, 2011 Rev. Ed.)

- Hussin Mutalib, 'Constituational-Electoral Reforms and Politics in Singapore', Legislative Studies Quarterly 21 (2) (2002), p. 664.

- Hussin Mutalib, 'Constituational-Electoral Reforms and Politics in Singapore', Legislative Studies Quarterly 21 (2) (2002), p. 666.

- Alex Au Waipang, 'The Ardour of Tokens: Opposition Parties' Struggle to Make a Difference', in T.Chong (eds), Management of Success: Singapore Revisited (Singapore, 2010), p. 106.

- Diane K. Mauzy and R.S. Milne, Singapore Under the People's Action Party (London, 2002), p.143.

- Bilveer Singh, Politics and Governance in Singapore: An Introduction (Singapore, 2007), p. 172.

- As of 15 April 2019.