Conservation and restoration of archaeological sites

The conservation and restoration of archaeological sites is the process of professionally protecting an archaeological site from further damage and restore it to a previous state. Archaeological sites require an extra level of care in regards to their conservation and restoration. Archaeology, even with thorough documentation, is a destructive force. This is because once a site has been even partially excavated, it cannot be put back the way it was, so to keep getting information from the site, it must be conserved to current best standards.

Life of a site

According to Ashurst and Shalom, archaeological sites have several phases.[1]

- Creation of the Site: During this phase, the site is in use and has been established.

- Deterioration: After the site has been abandoned, natural forces take hold of the area and begin to weaken any structures that have been built. Animals also burrow through the remnants, destroying floors, walls, and moving objects around. As walls and structures fall, they settle in different patterns and wind and water fill in the openings with dirt and dust.

- Identification: The site might be identified by archaeologists, or it might be identified by locals or other non-professionals.

- Excavation: There are many ways that an excavation can take place. One is that locals or other interested people decide that they want to investigate themselves. Whether this is simply for pot hunting (illegal digging and collecting of artifacts) or as more of an actual attempt at amateur excavation, it can easily damage the site and regularly makes interpretation more difficult. Even when excavated by professionals, sometimes improper techniques or documentation can actually lead to further damage. If done properly, archaeological excavations can reveal many aspects, while still protecting others and detailed documentation takes place to allow the site to be virtually reconstructed as best as possible.

- Further Deterioration: If the site is then left open, there is a renewal of deterioration since areas are now re-exposed to the weather.

- Ignorant Repair: There are many instances where people, with good intentions, attempt to conserve and repair a site. However, it results in more damage than assistance. Some ways that this happens is the use of inappropriate materials, inappropriate uses, as well as the lack of understanding of the original condition of the site (example: construction techniques, last used layout, et cetera).

- Correct Conservation: In this instance, correct conservation materials and techniques are used to preserve the condition the site was found in, and in rare cases rebuild where things have fallen over. The basic goal, however, is simply to preserve how it was found.

- Reburial: In the case that the site cannot be properly preserved while in the open (due to funding or other reasons), one of the better conservation techniques is simply to rebury the site to protect it from further deterioration.[2]

Many of these phases can be repeated and happen in a variety of orders.

Dangers

Weathering

The source of most damage is weather. Erosion through wind, rain, freeze-thaw, and evaporation are extremely common and other than covering the site entirely cannot be prevented. However, more dramatic factors are natural disasters: floods, fires, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, et cetera.[3] The best way to protect archaeological sites from these larger events is to formulate a risk management plan. The basics of this are to first identify what threatens the site the most and then determine its susceptibility to it. This plan is much like that for any structure or area, but there are no codes that must be upheld.

An example of how some locations deal with this is in Florida, which has many floods and much soil erosion. Florida has used easements that protect archaeological sites from such risks.[4]

Development

An unfortunate risk to archaeological sites is development itself. As the world continues to develop and build new buildings and roadways, many times archaeological sites are damaged. An example of this is in Arizona. There was an Ancient Puebloan site that dates to A.D. 900-1350 was damaged by construction activities while putting in a new road.[5] After the damage was assessed, it was determined that the site is not eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. However, this determination was made because there is not enough remaining for it to be of any "information important in prehistory or history."

While development cannot be discontinued simply to protect archaeological sites, having a basic understanding of what might be impacted before development takes place could help protect sites and at least the information they can provide. The Arizona Antiquities Act of 1960 is an example of some ways in which archaeological sites can be protected.[6]

Vandalism

Vandalism is also a prominent force of damage to archaeological sites. A range of actions can be considered, including graffiti, carving, deconstruction, and burning. These can be intentional or unintentional. Intentional vandalism is when visitors know that there is an archaeological site and yet still chose to harm it in some way. Unintentional vandalism happens when the visitor vandalizes while not realizing they are at an archaeological site.

An example of an unintentional vandalism is if someone is hunting small game and they see several rock around and decide to pile them up into a berm to shoot from behind. Unbeknownst to them, those rocks were not just naturally placed but actually a collapsed wall of an ancient building, with the majority of it underground. An example of intentional vandalism is graffiti. This can be considered intentional even if the visitors are unaware of the location being an archaeological site, because there is purposeful destruction even of a natural location. Tumamoc Hill in Tucson, Arizona has been subjected to this form of vandalism for centuries. Tumamoc Hill has a site on its top and has rock art all along the sides. It appears as though visitors throughout history have decided to join in on this tradition by adding their own initials and artwork.[7]

To protect an archaeological site from vandalism requires a combination of techniques. The most important is education of the public. This isn't just in terms of explaining that vandalism is bad—but to also educate them on the importance of these sites, and what can be lost if they vandalize the site. This can be as done as easily as adding signage. Another strategy is to discourage the activity through adding barriers, patrols, or even full-time observation. Another vital way to help is to routinely survey the area to track changes. This technique can also monitor weathering damage.[7]

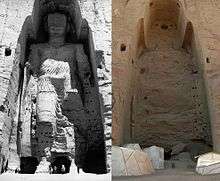

War

Throughout history, war has also caused much destruction of archaeological and historical sites. The Nazis during World War II destroyed many buildings during the planned destruction of Warsaw, including several palaces and other buildings dating back to before the 13th century. In more recent times, the Taliban destroyed the sacred Buddha statue in Afghanistan[8] and the ISIS YouTube videos.[9]

The prevention of this is virtually impossible without large-scale efforts such as those done by the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program that has become popularized by the 2014 movie The Monuments Men.

People involved

Archaeologists

The goal of archaeologists as well as other archaeological site conservators is "To preserve the physical remains of our past and to employ them in perpetuating our historical heritage."[10] The way an archaeologist can assist in this is to be as thorough in their documentation as possible. This way, even if the site is physically destroyed, there are existing records of how it once was. It is also important that archaeologists use excavation techniques that impact the site as little as possible and saves features. A current technique used is that the entire site is not actually excavated, only parts that are viewed as being able to answer research questions the best.[10][11]

A previous technique reconstructed walls and other site features to make it look more like it did originally. However, that has mostly gone out of style, and instead, preserving the site as found is more common.

Visitors

Visitors have some responsibility for archaeological site preservation. This goes beyond just vandalism. Even just their presence can be harmful for a site. An example of this happened at Recapture Canyon in Utah. In 2007, the United States Bureau of Land Management (BLM) had to close access to the canyon to off-road vehicles due to the damage it was causing local archaeological sites.[12] However, several visitors did not listen to this and actually created a wider trail through the canyon. Also, in May 2014 a large protest was held. This protest consisted of hundreds of protesters riding off-road vehicles through the canyon itself.[12][13] Owing to the large number of people going through in such a short amount of time, it is very possible that the protest itself caused further damage.

To combat further damage, archaeological sites that are open to the public are given trails that do not actually impact the site while still giving visitors a good view of it. It is important for visitors to understand their own impact on archaeological sites they visit. If there is a designated path, they should remain on it. If they see artifacts, they can point to them and take pictures but not pick them up and move them.

Conservators

Conservators are the leaders in going the extra mile for archaeological site conservation. It is these specialists that need to formulate the largest and longest-lasting plan. Martha Demas has created a great outline that conservators can rely on to create the most effective plan.[2][14]

- Identification and description

- Aims: What are the aims and expectations of the planning process?

- Stakeholders: Who should be involved in the planning process?

- Documentation and Description: What is known about the site and what needs to be understood?

- Assessment and Analysis

- Cultural Significance/Values: Why is the site important or valued and by whom is it valued?

- Physical Condition: What is the condition of the site or structure; what are the threats?

- Management Context: What are the current constraints and opportunities that affect the conservation and management of the site?

- Response

- Establish Purpose and Policies: For what purpose is the site being conserved and managed? How are the values of the site going to be preserved?

- Set Objectives: What will be done to translate policies into actions?

- Develop Strategies: How will the objectives be put into practice?

- Synthesize and Prepare Plan

- Periodic Review and Revision

Techniques

The purpose of any technique used on an archaeological site is to strengthen its ability to resist damage and/or reinstate its cultural significance and ability to teach about its history.

Restoration

Restoration is the "returning of the existing fabric of a place to a known earlier state by removing accretions or by reassembling existing components without the introduction of new material."[15] The biggest difficulty in this technique is the lack of introducing new material. Ideally, this is the primary technique to strengthen the site from further damage.

Reconstruction

Reconstruction is "returning a place to a known earlier state; distinguished from restoration by the introduction of new material into the fabric."[15] The aim of restoration is to "preserve and reveal the aesthetic and historic value of the monument and is based on respect for original material and authentic documents."[16]

There is also debate on whether this is conservation work or not, due to potential over-reconstruction.[15][17] The appropriateness of this technique is highly dependent upon the region, the amount of known knowledge of the site itself, as well as the actual condition of the site. The older a site, the more difficult it is to be confident in the reconstruction. Reconstruction should also be identifiable upon inspection as well as reversible.[17] A common form of reconstruction is the re-plastering of floors and walls. Due to weathering, the plaster that originally protected surfaces has eroded away and left the surfaces vulnerable. The re-plastering then adds that layer of protection back and in many cases was at least the same technique as originally even if it isn't exactly the same material.

Recreation/renovation

Recreation/renovation is the "speculative creation of a presumed earlier state on the basis of surviving evidence from that place to other sites, and on deductions drawn from that evidence using new materials."[15] This is the least favorable option as it is less likely to reinstate the originality of the site, and many times includes destroying existing authentic materials in order to add new materials. It is deemed justifiable if it is the only form of effective conservation available. or if conservation measures prove to be unfeasible.[16]

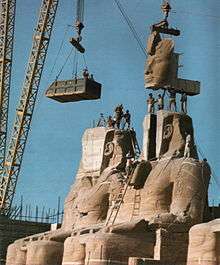

Relocation

Relocation is a dramatic form of conservation which involves the physical movement of the site or part of the site itself.[16] This should only take place if the site would be heavily damaged or even eliminated if it were to not be moved. A famous example of this is the move of the Abu Simbel temples. The movement of these temples was expensive as well as challenging, but if the move did not take place they would be completely underwater due to the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

Laws and policies

United States of America

- Antiquities Act of 1906[18]

- First United States law to provide protection of cultural heritage.

- Gives the President the authority to set aside land for the protection historic and prehistoric site and objects of historic or scientific significance; to be labeled as "National Monuments."

- Excavations and research on sites can only be done after a permit has been issued.

- Any artifacts collected must be curated in a museum or stored in a repository for preservation and public benefit.

- Proved ineffective in the 1970s as prosecution of looters failed.

- Replaced by the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (ARPA)

- Archeological and Historic Preservation Act (AHPA) (1974)[19]

- Also known as the Archeological Recovery Act or the Moss-Bennett bill

- Required Federal agencies to preserve "historical and archeological data (including relics and specimens) which might otherwise be irreparably lost or destroyed as the result of...any alteration of the terrain caused as a result of any Federal construction project of federally licensed activity or program (Section 1)."

- Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (ARPA)[20]

- Replaced the Antiquities Act of 1906.

- Outlined legal penalties that can be enforced on violators (such as looters).

- Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA)[21]

- Outlines treatment of cultural items, with which they can show a relationship of lineal descent or cultural affiliation.

- Affects federally funded institutions.

- Provides greater protection for Native American burial sites and more careful control over the removal of Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and items of cultural patrimony. Excavation or removal of any such items also must be done under procedures required by ARPA.

- Encourages the in situ preservation of archaeological sites, or at least the portions of them that contain burials or other kinds of cultural items.

- Affects previously acquired artifacts.

- Continues to be amended

- National Register of Historic Places[22]

- To be listed, site must meet at least one of four criteria:

- That are associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history

- That are associated with the lives of significant persons in or past

- That embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or that represent the work of a master, or that possess high artistic values, or that represent a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction

- That have yielded or may be likely to yield, information important in history or prehistory.

- Benefits of being listed:

- Entered into a National Database that is easily searchable by the public

- Encourages preservation and gain opportunities for specific grants, tax credits, preservation easements, and safety code alternatives

- Get additional resources for care and maintenance of property

- Get a bronze plaque to distinguish property as being part of the Register of Historic Places

- To be listed, site must meet at least one of four criteria:

References

- Ashurst, John; Shalom, Asi (2012). Reading 38: Short Story: The Demise, Discovery, Destruction and Salvation of a Ruin (2007) in "Archaeological Sites: Conservation and Management". Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute. p. 353-364.

- Demas, Martha. ""Site unseen": The Case for Reburial of Archaeological Sites". Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites. 6 (3–4): 137–154.

- Meier, Hans-Rudolf; Petzet, Michael; Will, Thomas (2008). Cultural Heritage and Natural Disasters (PDF). Germany: TUDpress.

- "Conservation Easements". Florida Division of Historical Resources. Florida Department of State.

- DeMar, David (May 15, 1996). The Result of a Damage Assessment and Limited Data Recovery Conducted at Site AZ-P-43-22 Located Near Pine Springs Wide Ruins Chapter, Fort Defiance Agency, Apache County, Arizona. Farmington, NM: San Juan County Museum Association.

- Haury, Emil. "The Arizona Antiquities Act of 1960". Kiva. 26 (1): 19–24.

- Hartmann, Gayle; Boyle, Peter (2013). New Perspectives on the Rock Art and Prehistoric Settlement Organization of Tumamoc Hill, Tucson, Arizona. Tucson: Arizona State Museum, The University of Arizona. ISBN 978-1-889747-93-4.

- Rashid, Ahmed. "After 1,700 Years, Buddhas fall to Taliban dynamite". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited.

- Perez, Chris. "ISIS ransacks museum, destroys 2,000-year-old artifacts". New York Post. NYP Holdings, Inc.

- South, Stanley (1976). The Role of the Archaeologist in the Conservation-Preservation Process in "Preservation and Conservation: Principles and Practices". Washington, D.C.: The Preservation Press. pp. 35–43.

- Marshall, John (2012). Reading 9: Conservation Manual (1923) in "Archaeological Sites: Conservation and Management". Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. pp. 47–49.

- Crandall, Megan. "BLM Statement Regarding Proposed Illegal ATV Ride in Recapture Canyon". BLM. Archived from the original on 2015-06-16. Retrieved 2015-05-02.

- Kuzmanic, Joyce. "Blanding: OHV riders, militia protest BLM ride through Recapture Canyon". St. George News.

- Demas, Martha (2012). Reading 64: Planning of Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites: A Values-Based Approach (2000) in "Archaeological Sites: Conservation and Management". Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. pp. 653–675.

- Woolfitt, Catherine (2012). Reading 51: Preventive Conservation of Ruins: Reconstruction, Reburial and Enclosure (2007) in "Archaeological Sites: Conservation and Management". Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. pp. 503–513.

- Petzet, Michael (2004). International Charters for Conservation and Restoration (PDF) (2 ed.). Germany: ICOMOS.

- Price, Nicholas (2012). Reading 52: The Reconstruction of Ruins: Principles and Practices (2009) in "Archaeological Sites: Conservation and Management". Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. pp. 514–527.

- "Antiquities Act of 1906". NPS Archaeology Program. National Park Service.

- "Archeological and Historic Preservation Act (AHPA)". NPS Archaeology Program. National Park Service.

- "Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979". NPS Archaeology Program. National Park Service.

- "Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act". NPS Archaeology Program. National Park Service.

- "National Register of Historic Places". National Park Services.