Common poorwill

The common poorwill (Phalaenoptilus nuttallii) is a nocturnal bird of the family Caprimulgidae, the nightjars. It is found from British Columbia and southeastern Alberta, through the western United States to northern Mexico. The bird's habitat is dry, open areas with grasses or shrubs, and even stony desert slopes with very little vegetation.

| Common poorwill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Caprimulgiformes |

| Family: | Caprimulgidae |

| Genus: | Phalaenoptilus Ridgway, 1880 |

| Species: | P. nuttallii |

| Binomial name | |

| Phalaenoptilus nuttallii Audubon, 1844 | |

| |

Many northern birds migrate to winter within the breeding range in central and western Mexico, though some remain further north. Remarkably, the common poorwill is the only bird known to go into torpor for extended periods (weeks to months).[2] This happens on the southern edge of its range in the United States, where it spends much of the winter inactive, concealed in piles of rocks. Such an extended period of torpor is close to a state of hibernation and is not known among other birds.

Taxonomy

The genus name Phalaenoptilus is a compound of Greek phalaina, moth and ptilon, feather. The species name nuttallii honors English-born American ornithologist Thomas Nuttall.[3]

Description

This is the smallest North American nightjar, about 18 centimetres (7.1 in) in length, with a wingspan of approximately 30 centimetres (12 in). It weighs 36–58 grams (1.3–2.0 oz). The sexes are similar, both gray and black patterned above. The outer tail-feathers are tipped with white, the markings slightly more prominent in the male.[4]

The common poorwill is told from similar nightjars by its small size, short bill, rounded wings with tips that reach the end of the short tail at rest, and pale gray coloration.[4] Like many other nightjars, the common name derives from its call, a monotonous poor-will given from dusk to dawn. At close range a third syllable of the call may be heard, resulting in a poor-will-low. It also gives a chuck note in flight.[4]

Behavior

The common poorwill is the only bird known to go into torpor for extended periods (weeks to months).[2] This happens on the southern edge of its range in the United States, where it spends much of the winter inactive, concealed in piles of rocks. This behavior has been reported in California and New Mexico. Such an extended period of torpor is close to a state of hibernation, not known among other birds. It was described definitively by Dr. Edmund Jaeger in 1948 based on a poorwill he discovered hibernating in the Chuckwalla Mountains of California in 1946.[5]

In 1804, Meriwether Lewis observed hibernating common poorwills in North Dakota during the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Though these observations were recorded carefully in Lewis's journal, their significance was not understood. This was at least in part because the common poorwill was not then recognized as a species distinct from the whip-poor-will of eastern North America. Native Americans of the Hopi tribe were likely aware of the poorwill's behavior even earlier — the Hopílavayi name of this bird, hölchko, means "The Sleeping One".[6][7][8]

Breeding is from March to August in the south of the range, and late May to September further north. The nest of the common poorwill is a shallow scrape on the ground, often at the base of a hill and frequently shaded partly by a bush or clump of grass. The clutch size is typically two, and the eggs are white to creamy, or pale pink, sometimes with darker mottling. Both sexes incubate for 20–21 days to hatching, with another 20–23 days to fledging.[6] There is usually one brood per year, but females may sometimes lay and incubate a second clutch within 100 m of the first nest while the male feeds young at the first site. The young are semiprecocial. An adult disturbed on the nest tumbles and opens its mouth, hissing, apparently imitating a snake.

Like other members of this family it feeds on nocturnal insects such as moths, beetles, and grasshoppers.[6] It ejects pellets of the indigestible parts, in the manner of an owl. The common poorwill frequently takes prey off of the ground or by leaping into the air from the ground. It is reported to drink on the wing.

Subspecies

Up to five subspecies are described, although these are all quite similar, and some may be of dubious validity.

- P. n. nutalli breeds over most of the North American range.

- P. n. californicus, dusky poorwill, is darker and browner than the nominate race. It occurs in western California.

- P. n. hueyi, desert poorwill, is paler than the nominate race. It occurs in southern California.

- P. n. dickeyi, San Ignacio poorwill, is smaller and less heavily marked than californicus. It is resident in Baja California.

- P. n. adustus, Sonoran poorwill, is paler and browner than the nominate race. It occurs from extreme southern Arizona to central Sonora.

References

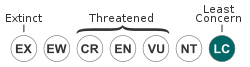

- BirdLife International (2012). "Phalaenoptilus nuttallii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKechnie, Andrew W.; Ashdown, Robert A. M.; Christian, Murray B.; Brigham, R. Mark. "Torpor in an African caprimulgid, the freckled nightjar Caprimulgus tristigma" (PDF). Journal of Avian Biology. 38 (3): 261–266. doi:10.1111/j.2007.0908-8857.04116.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Mearns, Richard and Barbara. Audubon to Xantus. ISBN 0-12-487423-1.

- "Common Poorwill". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Jaeger, Edmund (January 1951). "Poorwill Sleeps Away the Winter". National Geographic Society.

- "Audubon Society -- Common Poorwill".

- Ryser, Fred A. (1985). Birds of the Great Basin: A Natural History. University of Nevada Press. p. 305. ISBN 0-87417-080-X.

- Bagemihl, Bruce (2000-04-10). Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity. Macmillan. ISBN 9781466809277.

- Cleere and Nurney, 1998. Nightjars, ISBN 1-873403-48-8

- Paul R. Ehrlich; David S. Dobkin; and Darryl Wheye, 1988. The Birder's Handbook. New York: Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0-671-62133-5

- Terres, 1980. Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 0-394-46651-9

- National Geographic Society, 1987. Field Guide to the Birds of North America. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-7922-7451-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phalaenoptilus nuttallii. |

- USGS

- All About Birds – Cornell University

- Arizona State University

- Jaeger's discovery – several articles discuss history of observations of hibernation in the Poorwill

- San Bernardino County Museum – refers to Wilson Hanna, oologist

- Common Poorwill photo gallery VIREO