Caprimulgiformes

The Caprimulgiformes is an order of birds that includes a number of birds with global distribution (except Antarctica). They are generally insectivorous and nocturnal. The order gets its name from the Latin for "goat-milker", an old name based on an erroneous view of the European nightjar's feeding habits.

| Caprimulgiformes Temporal range: Middle Paleocene to present | |

|---|---|

| |

| Large-tailed nightjar, Caprimulgus macrurus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Strisores |

| Order: | Caprimulgiformes Ridgway, 1881 |

| Families[1] | |

| |

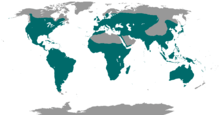

| Global distribution of the nightjar and allies | |

Systematics

The classification of the various birds that make up the order has long been controversial and difficult, particularly in the case of the nightjars and the paraphyly of the traditional Caprimulgiformes in relation to "Apodiformes", traditionally considered a separate order.

The IUCN adopts the following classification of Order Caprimulgiformes,[1] which follows recent phylogenetic studies:

- Family Trochilidae (hummingbirds, 368 species)

- Family Apodidae (swifts, 96 species)

- Family Caprimulgidae (nightjars, 98 species)

- Family Podargidae (frogmouths, 14 species)

- Family Aegothelidae (owlet-nightjars, 10 species)

- Family Nyctibiidae (potoos, 7 species)

- Family Hemiprocnidae (treeswifts, 4 species)

- Family Steatornithidae (oilbird, 1 species)

The IUCN definition renders the order Caprimulgiformes identical to the clade Strisores. Authorities that favor the use of Strisores for this group (e.g., Yuri et al. 2013[2] and Chen et al. 2019[3]) adopt a sensu stricto definition definition of the order, limiting to the family Caprimulgidae. They also elevate many (or even all) of the families traditionally placed in Caprimulgiformes to ordinal rank.[2] This requires recognizing at least three additional orders: Nyctibiiformes, Steatornithiformes, and Podargiformes. Owlet-nightjars can be placed in their own order (Aegotheliformes)[2] or viewed as a family within Apodiformes.[4]

Traditionally, Caprimulgiformes were regarded, on morphological grounds, as being midway between the owls (Strigiformes) and the swifts. Like the owls, they are nocturnal hunters with a highly developed sense of sight, and like the swifts they are excellent flyers with small, weak legs. At one time or another, they have been allied with owls, swifts, kingfishers, hoopoes, mousebirds, hornbills, rollers, bee-eaters, woodpeckers, trogons and hummingbirds. A close relationship to owls can be rejected since there is strong molecular evidence[5][6] that owls are members of a clade, called Telluraves, that excludes Caprimulgiformes.

Based on analysis of DNA sequence data – notably β-fibrinogen intron 7 – Fain and Houde considered the families of the Caprimulgiformes to be members of the proposed clade Metaves, which also includes the hoatzin, tropicbirds, sandgrouse, pigeons, kagu, sunbittern, mesites, flamingos, grebes and swifts and hummingbirds.[7] Metaves was also found by the expanded study of Ericson et al. (2006), but support for the clade was extremely weak.[8]

While only the latter study recovered monophyly of the Cypselomorphae (see below) within Metaves, the former was based on only a single locus and could not resolve their relationships according to standard criteria of statistical confidence. No morphological synapomorphies have been found that uniquely unite Metaves (or Caprimulgiformes for that matter), but numerous unlinked nuclear genes independently support their monophyly either in majority or whole. Ericson et al. (2006) concluded that if valid, the "Metaves" must originate quite some time before the Paleogene, and they reconciled this with the fossil record.[8]

While the relationships of cypselomorphs are a subject of ongoing debate, the phylogeny of the individual lineages is better resolved. Much of the remaining uncertainty regards minor details.

Initial mtDNA cytochrome b sequence analysis[9] agreed with earlier morphological[10] and DNA-DNA hybridization[11] studies insofar as that the oilbird and the frogmouths seemed rather distinct. The other lineages appeared to form a clade, but this is now known to have been caused by methodological limitiations.

The Aegothelidae (owlet-nightjars) with about a dozen living species in one genus are apparently closer to the Apodiformes; these and the Caprimulgiformes are closely related, being grouped together as Cypselomorphae. The oilbird and the frogmouths seem quite distinct among the remaining Caprimulgiformes, but their exact placement cannot be resolved based on osteological data alone.[12]

Even the study of Ericson et al. could not properly resolve the oilbird's and frogmouths' relationships beyond the fact that they are quite certainly well distinct. It robustly supported, however, the idea that the owlet-nightjars should be considered closer to Caprimulgiformes, unlike the methodologically weaker studies of Mariaux & Braun (1996)[9] and Fain and Houde (2004).[7]

Alternatively, Mayr's phylogenetic taxon Cypselomorphae might be placed at order rank and substitute the two present orders Caprimulgiformes and Apodiformes. Such a group would be fairly uninformative as regards its evolutionary history, as it has to include some very plesiomorphic and some extremely derived lineages (such as hummingbirds) to achieve monophyly.[12] Reddy et al. (2017)[13] included hummingbirds and swifts in Caprimulgiformes, preserving the monophyly of the order.

The following cladogram follows the results of Mayr's (2002) phylogenetic study,[12] which used a parsimony analysis of 25 morphological characters:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Subsequent molecular work has converged on two alternative topologies (topologies 1 and 2 below) that differ in the placement of the root.[14] Although Braun et al. (2019)[14] suggested that topology 1 was favored in large-scale analyses of non-coding data were analyzed and that topology 2 was favored in large-scale analyses of coding data (e.g., Prum et al. (2015)[15]) subsequent analyses of datasets with many non-coding loci[3][16] have also recovered topology 2. Thus, topology 2 should be viewed as the best-corroborated hypothesis at this time.

Topology 1: phylogeny according to Reddy et al. (2017),[13] which analyzed 54 nuclear loci (mostly introns):

| Caprimulgiformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Topology 2: phylogeny according to Prum et al. (2015)[15] (259 "anchored hybrid enrichment" loci, which are mostly coding exons), Chen et al. (2019)[3] (combined analysis of 2289 ultra-conserved elements [UCEs] and 117 morphological characters and including fossil taxa), and White and Braun (2019)[16] (based on analyses of multiple UCE datasets, ranging in size from 2289 to 4243 loci):

| Caprimulgiformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chen et al. (2019)[3] proposed the name Vanescaves for the clade comprising all Caprimulgiformes (=Strisores) except Caprimulgidae. White and Braun (2019)[16] acknowledged that some uncertainty remains; specifically, monophyly of the clade comprising Steatornithidae and Nyctibiidae was limited and that three different resolutions of Steatornithidae, Nyctibiidae, and the clade comprising Podargidae and Daedalornithes remain plausible. However, they viewed topology 2 as the best-supported hypothesis.

Evolution

The fossil record of caprimulgiform birds is actually rather extensive; Chen et al. (2019)[3] included 14 fossil lineages in their anallyssis. Nonetheless, it supports the emerging consensus phylogeny well. The genus Paraprefica, probably from the Early Eocene (though this is somewhat uncertain), seems to be a basal form that at times has been allied with the oilbird and the potoos, but cannot be assigned to either with certainty. In the consensus scenario, it would represent a record of the initial divergence of the three lineages.

This nicely agrees with fossils suggesting that the basal divergence of the owlet-nightjar and apodiform branch also occurred during that time. In addition, Eocypselus, a Late Paleocene or Early Eocene genus of north-central Europe, cannot be assigned to any one cypselomorph lineage with certainty but appears to be some ancestral form.

These Paleogene birds strongly suggest that the two main extant lineages of cypselomorphs separated about 60-55 mya (Selandian-Thanetian), and that some time around the Lutetian-Bartonian boundary, some 40 mya, the common ancestors of Nyctibiidae, Caprimulgidae and eared nightjars diverged from those of oilbird and frogmouths.

Reproduction

Caprimulgiform birds typically lay small clutches: frogmouths and potoos lay only one egg, with exceptions such as the Australian Tawny Frogmouth which lay two to three and Marbled Frogmouth which lay one to two; nightjars one or two, and the Oilbird usually three. With the exception of the Oilbird, which nests colonially in tree hollows, caprimulgiform birds do not build a nest but lay their egg or eggs directly onto the ground or branches. Both parents usually incubate, and for camouflage the semialtricial chicks, covered with down at hatching but immobile, are often coloured white like the eggs.

Little is known of the life history of many members of the order[17] especially of maximum lifespans and age at first breeding. Most caprimulgiforms are monogamous, with the same pair breeding for many years, though only the eared nightjars typically produce more than a single brood per year.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caprimulgiformes. |

References

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- Yuri, Tamaki; Kimball, Rebecca; Harshman, John; Bowie, Rauri; Braun, Michael; Chojnowski, Jena; Han, Kin-Lan; Hackett, Shannon; Huddleston, Christopher; Moore, William; Reddy, Sushma (2013-03-13). "Parsimony and Model-Based Analyses of Indels in Avian Nuclear Genes Reveal Congruent and Incongruent Phylogenetic Signals". Biology. 2 (1): 419–444. doi:10.3390/biology2010419. ISSN 2079-7737. PMC 4009869. PMID 24832669.

- Chen, Albert; White, Noor D.; Benson, Roger B.J.; Braun, Michael J.; Field, Daniel J. (2019-08-23). "Total-Evidence Framework Reveals Complex Morphological Evolution in Nightbirds (Strisores)". Diversity. 11 (9): 143. doi:10.3390/d11090143. ISSN 1424-2818.

- "ITIS Standard Report Page: Aegothelidae". www.itis.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- Hackett, S. J.; Kimball, R. T.; Reddy, S.; Bowie, R. C. K.; Braun, E. L.; Braun, M. J.; Chojnowski, J. L.; Cox, W. A.; Han, K.-L.; Harshman, J.; Huddleston, C. J. (2008-06-27). "A Phylogenomic Study of Birds Reveals Their Evolutionary History". Science. 320 (5884): 1763–1768. doi:10.1126/science.1157704. ISSN 0036-8075.

- Jarvis, E. D.; Mirarab, S.; Aberer, A. J.; Li, B.; Houde, P.; Li, C.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Faircloth, B. C.; Nabholz, B.; Howard, J. T.; Suh, A. (2014-12-12). "Whole-genome analyses resolve early branches in the tree of life of modern birds". Science. 346 (6215): 1320–1331. doi:10.1126/science.1253451. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 4405904. PMID 25504713.

- Fain, Matthew G.; Houde, Peter (2004). "Parallel radiations in the primary clades of birds" (PDF). Evolution. 58 (11): 2558–2573. doi:10.1554/04-235. PMID 15612298. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-07.

- Ericson, Per G.P.; Anderson, Cajsa L.; Britton, Tom; Elżanowski, Andrzej; Johansson, Ulf S.; Källersjö, Mari; Ohlson, Jan I.; Parsons, Thomas J.; Zuccon, Dario; Mayr, Gerald (2006). "Diversification of Neoaves: integration of molecular sequence data and fossils" (PDF). Biology Letters. 2 (4): 543–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0523. PMC 1834003. PMID 17148284. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-03-07.

- Mariaux, Jean; Braun, Michael J. (1996). "A Molecular Phylogenetic Survey of the Nightjars and Allies (Caprimulgiformes) with Special Emphasis on the Potoos (Nyctibiidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 6 (2): 228–244. doi:10.1006/mpev.1996.0073. PMID 8899725. S2CID 10538534.

- Cracraft, Joel (1981). "Toward a phylogenetic classification of the recent birds of the world (Class Aves)" (PDF). Auk. 98 (4): 681–714. JSTOR 4085891.

- Sibley, Charles Gald and Ahlquist, Jon Edward (1990): ThePhylogeny and classification of birds. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn., ISBN 0-300-04085-7

- Mayr, Gerald (2002). "Osteological evidence for paraphyly of the avian order Caprimulgiformes (nightjars and allies)". Journal für Ornithologie. 143 (1): 82–97. doi:10.1007/bf02465461.

- Reddy, Sushma; Kimball, Rebecca T.; Pandey, Akanksha; Hosner, Peter A.; Braun, Michael J.; Hackett, Shannon J.; Han, Kin-Lan; Harshman, John; Huddleston, Christopher J.; Kingston, Sarah; Marks, Ben D. (2017-09-01). "Why Do Phylogenomic Data Sets Yield Conflicting Trees? Data Type Influences the Avian Tree of Life more than Taxon Sampling". Systematic Biology. 66 (5): 857–879. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syx041. ISSN 1063-5157. PMID 28369655.

- Braun, Edward L.; Cracraft, Joel; Houde, Peter (2019), Kraus, Robert H. S. (ed.), "Resolving the Avian Tree of Life from Top to Bottom: The Promise and Potential Boundaries of the Phylogenomic Era", Avian Genomics in Ecology and Evolution, Springer International Publishing, pp. 151–210, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-16477-5_6, ISBN 978-3-030-16476-8, retrieved 2020-06-07

- Prum, Richard O.; Berv, Jacob S.; Dornburg, Alex; Field, Daniel J.; Townsend, Jeffrey P.; Lemmon, Emily Moriarty; Lemmon, Alan R. (October 2015). "A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing". Nature. 526 (7574): 569–573. doi:10.1038/nature15697. ISSN 0028-0836.

- White, Noor D.; Braun, Michael J. (December 2019). "Extracting phylogenetic signal from phylogenomic data: Higher-level relationships of the nightbirds (Strisores)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 141: 106611. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106611.

- Cleere, Nigel (2010) Nightjars of the world : potoos, frogmouths, oilbird and owlet-nightjars, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-14857-0